John Alford at Airshow Interview with John Leroy Alford, March 13, 2018 Page 2 of 39

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aa000343.Pdf (12.91Mb)

COMFORT SHOE New Style! New Comfort! Haband’s LOW 99 PRICE: per pair 29Roomy new box toe and all the Dr. Scholl’s wonderful comfort your feet are used to, now with handsome new “D-Ring” MagicCling™ closure that is so easy to “touch and go.” Soft supple uppers are genuine leather with durable man-made counter, quarter & trim. Easy-on Fully padded foam-backed linings Easy-off throughout, even on collar, tongue & Magic Cling™ strap, cradle & cushion your feet. strap! Get comfort you can count on, with no buckles, laces or ties, just one simple flick of the MagicCling™ strap and you’re set! Order now! Tan Duke Habernickel, Pres. 1600 Pennsylvania Ave. Peckville, PA 18452 White Black Medium & Wide Widths! per pair ORDER 99 Brown FREE Postage! HERE! Imported Walking Shoes 292 for 55.40 3 for 80.75 Haband 1600 Pennsylvania Ave. 1 1 D Widths: 77⁄2 88⁄2 9 Molded heel cup Peckville, Pennsylvania 18452 1 1 NEW! 9 ⁄2 10 10 ⁄2 11 12 13 14 with latex pad COMFORT INSOLE Send ____ shoes. I enclose $_______ EEE Widths: positions foot and 1 1 purchase price plus $6.95 toward 88⁄2 9 9 ⁄2 Perforated sock and insole 1 adds extra layer 10 10 ⁄2 11 12 13 14 for breathability, postage. of cushioning GA residents FREE POSTAGE! NO EXTRA CHARGE for EEE! flexibility & add sales tax EVA heel insert for comfort 7TY–46102 WHAT WHAT HOW shock-absorption Check SIZE? WIDTH? MANY? 02 TAN TPR outsole 09 WHITE for lightweight 04 BROWN comfort 01 BLACK ® Modular System Card # _________________________________________Exp.: ______/_____ for cushioned comfort Mr./Mrs./Ms._____________________________________________________ ©2004 Schering-Plough HealthCare Products, Inc. -

American Naval Forces at Kawajalein, Task Force 52, 30

American Naval and Landing Forces at Kawajalein Task Force 52 & 53 30 January 1944 Southern Attack Force: Admiral R.K.Turner Flag Force USS Rockey Mount Support Aircraft, TG 52.1: Captain H.B.Sallada assigned aircraft unknown Southern Landing Force: Major General C.Corlette 7th Infantry Division: Major General C.Corlette Attached Southern Garrison Force: Brigadier General Gibson Southern Base Support Aircraft: Colonel Collar Channel Island Transport Group TG52.3: LCDR D.K.O`Conner USS Manley USS Overton Advance Transport Group TU 52.5.1 : Captain J.B.McGovern Transport Division 4: Captain J.B.McGovern USS Zelin USS Ormsby USS Windsor USS President Polk USS Virgo USS Ashland Tractor Unit No. 1: CDR R.C.Webb, Jr. 1 LST Unit 8 LSTs LCT Unit (Deck Load) 3 LCTs Southern Transport Unit, TG 52.5: Captain H.B.Knowles Transport Division 6: Captain T.B.Brittan USS Harris USS Fayette USS Harry Lee USS Leedstown USS Centaurus USS Lindwalden Transport Division 18 Captain HG.B.Kowles USS Monrovia USS J.F.Bell USS Pierce USS Feland USS Thuban USS Belle Grove Tractor Unit No. 2: CDR A.M.Hurst 1 LST Unit 8 LSTs LCT Unit (Deck Load) 3 LCTs 1 Control Group, TG 52.7 CDR Coleman SC Unit 3 SCs LCC Unit 2 LCCs Transport Screen, CTG 52.7: Captain E.M.Thompson USS John Rogers (DD574) USS Hazelwood (DD531) Southern Transport Screen TU 5.2.7.2: Captain Crommelin USS Franks (DD554) USS Haggard (DD555) USS Hailey (DD556) USS Perry (DMS17) USS Schroeder (DD501) USS Zane (DMS14) SC Unit 2 SCs Fire Support Group, TG 52.8: Rear Admiral R.C.Giffen Fire Support Unit No. -

Beck 1-1000 Numbered Checklist 1962-1975

Free checklist, download at http://www.beck.ormurray.com/ Beck Number QTY W=Winick B "SPACE" Ship/Location Hull Number Location Cachet/ Event Cancel Date MT, Comment BL=Beck Log, If just a "LOW" number, it means that both Hand agree. "CREW" 1-Prototype No record of USS Richard E Byrd DDG-23 Seattle, WA Launching FEB 6/?130PM/1962 MT No Beck number. count 1-Prototype No record of USS Buchanan DDG-14 Commission FEB/7/1962/A.M. HB No Beck number. count 1-Prototype No record of USS James Madison SSBN-627 Newport News, Keel Laying MAR 5/930 AM/1962 MT No Beck number count VA Prototype No record of USS John C Calhoun SSBN-630 Newport News, Keel Laying MT No Beck number count VA JUN 4/230PM/1962 Prototype No record of USS Tattnall DDG-19 Westwego, LA Launching FEB 13/9 AM/1962 HT count 1-"S" No record of USS Enterprise CVAN-65 Independence JUL/4/8 AM/1962 HB count Day 1 43 USS Thomas Jefferson SSBN-618 Newport News, Launching FEB/24/12:30PM/1962 MT VA 2 52 USS England DLG-22 San Pedro, CA Launching MAR 6/9AM/1962 MT 3 72 USS Sam Houston SSBN-609 Newport News, Commission MAR 6/2PM/1962 MT VA 3 USS Sam Houston SSBN-609 Newport News, Commission MR 06 2 PM/1962 HT eBay VA 4 108 USS Thomas A Edison SSBN-610 Groton, CT Commission MAR 10/5:30PM/1962 MT 5 84 USS Pollack SSN-603 Camden, NJ Launching MAR17/11-AM/1962 MT 6 230 USS Dace SSN-607 Pascagoula, Launching AUG 18/1962/12M MT MS 6 Cachet Variety. -

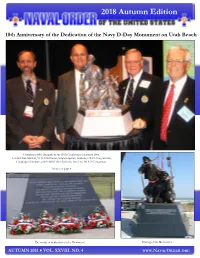

2018 Autumn Edition

2018 Autumn Edition 10th Anniversary of the Dedication of the Navy D-Day Monument on Utah Beach Unveiling of the Maquette at the SNA Conference in Jan uary 2006. L to R: Dean Mosher, NOUS Historian; Stephen Spears, sculptor; CAPT Greg Streeter, Campaign Chairman; and VADM Mike Kalleres, 1st Coast NOUS Companion. Article on page 4 The words of dedication on the Monument Placing of the Monument AUTUMN 2018 ● VOL. XXVIII, NO. 4 WWW.NAVALORDER.ORG COMMANDER GENERAL ’S REPORT TO THE ORDER 2018 Congress in San Antonio - What to On Saturday morning, 27 October, after a continental breakfast, remaining national officer reports will be made followed by a Look Forward to…or What You’re Missing presentation by citizen sailor, businessman and author, CAPT The Texas Commandery is hosting the 2018 Congress at the Mark Liebmann. Wyndam San Antonio Riverwalk from Wednesday, 24 The Admiral of the Navy George Dewey Award/Commander October through 27 October and assures us that our visit to General Awards Luncheon will recognize Mr. Marshall Cloyd, the Lone Star state will be most memorable. recipient of The Admiral of the Navy George Dewey Award. Although the Congress doesn’t officially start until Additionally, RADM Douglas Moore, USN (Ret.) will Wednesday, we will visit the National Museum of the Pacific receive the Distinguished Alumnus Award by the Navy Supply Corps Foundation. War (Nimitz Museum) in Fredericksburg, TX on Tuesday, 23 October. Similar to the National World War II Museum that After lunch a presentation will be made by James Hornfischer, one many of us visited during our 2015 Congress in New of the most commanding naval historians writing today. -

RAYNOR ANDREW KENT TAYLOR Rear Admiral Raynor A. K. Taylor

RAYNOR ANDREW KENT TAYLOR Rear Admiral Raynor A. K. Taylor, age 77, passed away September 3, 2013 from cancer and congestive heart failure. He died at his home in Virginia Beach. He was born to Raynor and Doris M. (Santos) Taylor in New Bedford, Massachusetts on December 22, 1935. He grew up with his loving sisters Jeanne and Lynne, and brother Jeffrey. He was a 1953 graduate of New Bedford High School where he excelled in math, physics and geography. He attended Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute on an academic scholarship for two years before earning a competitive Congressional appointment to the United States Naval Academy. As a member of the USNA Class of 1960 he was editor of the yearbook, the Lucky Bag. After graduation Ray married the love of his life Mary Jane Stevens of Newport News, Virginia. Together they enjoyed his thirty-three year Navy career which was always, both personally and professionally, rewarding and demanding. Rear Admiral Taylor was a nuclear trained Surface Warfare Officer. He served in the engineering departments of USS ABBOT (DD-629) and USS HOEL (DDG-13). He was Main Propulsion Assistant USS ENTERPRISE (CVN-65) and Executive Officer USS HALSEY (CG-23) Command tours included Commanding Officer USS SEMMES (DDG- 18), Commanding Officer USS MISSISSIPPI (CGN-40) and Commanding Officer Surface Warfare Officers School. As COMCRUDESGRUONE he commanded the NEW JERSEY Battle Group, the Navy's first modern era battleship battle group. Overseas tours provided lasting memories and learning. He was an Olmsted Scholar at the University of Grenoble, France 1967 -1969, earning a Diplome d'Etat in Political Science followed by a Masters of Arts in Area Studies from American University, Washington, D.C. -

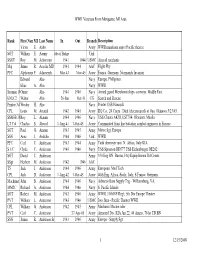

WWII Veterans from Marquette, MI Area Rank First Amemi Last Ame in out Branch Description Victor E. Aalto Army WWII Munitions Su

WWII Veterans From Marquette, MI Area Rank First ameMI Last ame In Out Branch Description Victor E. Aalto Army WWII munitions supvr Pacific theatre SGTWWII, combat William inf. Europe, E. Aarmy Dday, Battle of Bulge Unk SSGT Roy M. Ackerman 1941 1944 USMC Aircraft mechanic Maj James R. Acocks MD 1941 1944 AAC Flight Phy PFC Alphonsus F. Adamezyk Mar-43 Nov-45 Army France, Germany, Normandy Invasion. Edward Aho Navy Europe, Phillipines Elias A. Aho Navy WWII Seaman 1ClassOnnie Aho 1944 1946 Navy Armed guard Merchanat ships- convoys. Middle East. ENLC2 Walter Aho 26-Jun Oct-51 CG Search and Rescue Printer 3d Wesley H. Aho Navy Printer USS Hancock CPL Louis M. Airaudi 1942 1945 Army HQ Co., 24 Corps. Died (electrocuted) at Osa, Okinawa 5/23/45. SSM-B 3C Roy L. Alanen 1944 1946 Navy USS Chaara AK58, LST704. Okinawa, Manila LT Col Charles B. Alvord 1-Aug-41 1-Oct-45 Army Commanded front line battalion combat engineers in Europe SGT Paul G. Ameen 1943 1945 Army Motor Sgt, Europe SSG Arne J. Andelin 1944 1946 Unk WWII PFC Carl C. Anderson 1943 1944 Army Tank destroyer unit. N. Africa, Italy.KIA S 1/C Clyde C. Anderson 1945 1946 Navy USS Sproston DD577 USS Eichenberger DE202 SGT David C. Anderson Army 330 Eng BN. Burma. Hvy Equip Burma Rd Constr. SSgt Herbert M. Anderson 1942 1946 AAC T5 Jack I. Anderson 1944 1946 Army European. Med Tech CPL Jack D. Anderson 1-Aug-42 1-Oct-45 Army 40th Eng. Africa, Sicily, Italy, S France, Germany. -

US Naval Forces, Tanahmerah Bay, Humboldt Bay

US Naval Forces Tanahmerah Bay, Humboldt Bay, Aitape 22 April 1944 Task Force 77: Rear Admiral D.E.Barbey USS Blue Ridge Task Group 77.1 (Western Attack Force: Rear Admiral D.E.Barbey USS Swanson (DD Transport Group: USS H.T.Allen USS Manoora USS Kanimbla USS Carter Hall USS Triangulum LCIs: LCDR J.Hurndall. 15 LCIs LST's: CDR T.C.Green 7 LSTs Destroyers: CDR W.S.Veeder USS Hobby (DD610) USS Nicholson (DD442) USS Wilkes (DD441) USS Grayson (DD435) USS Gillespie (DD609) USS Kalk (DD611) Special Service Vessels: Captain N.D.Brantley Reserve: LCDR G.A.Keith, RANVR 1 AT 2 SCs 1 LCI 2 YMSs Beachmaster Unit No. 3: LCDR E.R.Hollran Task Group 77.2 Central Attack Group Rear Admiral W.M.Fechteler USS Reid (DD369) Transports: CDR A.V.Knight RANR USS Westralia (APA) USS Guston Hall (LSD) USS Ganymede (AK) USS Brooks (DD232) USS Gilmer (DD233) USS Herbert (DD160) USS Humphreys (DD 236) USS Sands (DD243) LCI Group: CDR H.F.McGee 16 LCIs LSTs: Captain R.M.Scruggs 7 LSTs Destroyers: Captain R.F.Stout USS Roe (DD418) USS Radford (DD446) USS Stevenson (DD503) USS Stockton (DD504) USS Thorn (DD505) 1 USS Taylor (DD468) USS Welles (DD628) Special Service Vessels: Captain B.Anderson USS Hovey (DMS11) USS Long (DMS12) USS Sonoma 2 LCIs 2 YMSs 2 SCs Beachmaster Unit No. 4: LT(jg) E.J.Zinzer Task Group 77.3, Eastern Attack Group: Captain A.G.Noble Transports CDR D.L.Mattie USS Kilty USS Ward USS Crosby USS Dickenson USS Talbot USS Schley USS Kane USS Dent USS Noa USS Epping Forest USS Etamin LSTs: LCDR D.M.Baker 7 LSTs Destroyers Captain W.D.Chandler USS Hopewell (DD681) USS Howorth (DD592) USS Jenkins (DD447) USS Nicholas (DD449) USS O'Bannon (DD450) Special Service Vehicles: Captain J.W.Jamison USS Hamilton (DMS18) USS Perry (DMS17) USS Chetco 4 SCs 2 YMSs Beachmaster Unit No. -

Picket Duty Rules – Version 3

1.0 Components 1.1.1 Compartments & Equipment A. There are two types of compartments: Primary The following items are included in the game: (located on the map) and Secondary Ω (located on a Tactical Map separate sheet (See Rule 1.7). Counters – 5 sheets (160 x 1.2” + 240 x .6”) The Primary compartments are located in three Rule Book sections of the ship, labeled as: Charts & Scenario Book Forward - Repair Section 1 Player Aids – 4 sheets Midship - Repair Section 2 1. Ship’s Log Aft - Repair Section 3. 2. Time Sheet 3. Firing Reference Tables B. A blue background in the compartment name 4. Secondary Compartment Sheet Ω indicates it can be flooded due to damage or to correct One 10- sided (d10) die + two 6-sided (d6) dice. trim and list. C. Equipment consists of the 5 in. and 40mm gun 1.1 The Map directors (also called gun controllers), and shipboard radar. The upper half of the map contains tracks and boxes to indicate or track the following: 1.2 Map Tracks & Boxes Station Assignment & Surface Fire Support 1.2.1 Tracks Air Fire Support and FDT availability Ship and Land based radar levels There are five (5) tracks on the map that are used to Ship morale level record the level of damage to the destroyer, the Current status of compartments & equipment expenditure of ships stores and its ability to Levels of the ship’s fuel, ammo, hull damage, and maneuver. maneuvering level 1. Ammo Supply – records the amount of Time of Day and Weather ammunition remaining. -

PICKET DUTY RULES – VERSION 2 May 10, 2014

PICKET DUTY RULES – VERSION 2 May 10, 2014 1.0 -- GAME COMPONENTS C. Equipment consists of the 5 in. and 40mm gun directors, and shipboard radar. The following items are included in the game: Tactical Map, Counters – 5 sheets (160 x 1.2” and 240 x .6 ” ), 1.2 Map Tracks & Boxes Rule Book, Charts & Scenario Book, Player Aids – 4 1.2.1 Tracks charts (Ship’s Log, T i m e Sheet, Firing Reference Tables, Secondary Compartment Sheet Ω), One 10- There are five (5) tracks on the map that are used to sided (d10) die and two 6-sided (d6) dice. record the level of damage to the destroyer, the expenditure of ships stores and its ability to maneuver. 1.1 -- The Map 1. Ammo Supply – records the amount of ammunition The upper half of the map contains tracks and boxes to remaining. When the track reaches “0” you are out of indicate or track the following: Station Assignment & ammo and must return to anchorage for refit. Surface Fire Support, Air Fire Support and FDT availability, Ship and Land based radar levels, Ship 2. Hull Integrity – records damage to the hull during the morale level, Current status of compartments & game. When it reaches zero your ship may sink. equipment, Levels of various ships wares and damage, 3. Maneuvering – records the ship’s ability to Time of Day and Weather, Gun Director Damage, maneuver. As the ship takes damage in certain areas, it Damage Control Team assignments, Flooding and List & loses the ability to maneuver. Trim, and Japanese Waves and Special Attack aircraft. -

Bright Penny

T H E BRIGHT PENNY July 2007 A NEWSLETTER FOR MEMBERS OF THE USS BERKELEY (DDG-15) ASSOCIATION Since I've become director, Master Chief Duane LeDoux completed our membership has his sophomore year in high school in increased by 34 members. LaPorte, Indiana in 1951. He then moved I'm hoping to see, by the on to the East Coast in the Cohasset, year’s end, that we will have Massachusetts’s area. Realizing his increased our membership quest for greener pastures was not by at least 50 new members. working out; he tried to join the U.S. I've also been working on Marine Corp, but was not accepted due the plans for our 2008 reunion in Boston to be to physical disqualifications. He then moved on to what became the held July 31, August 2 & 3. As noted in the beginning of his naval career. The Navy last newsletter, it will be held at the Sheraton took care of correcting his physical Braintree. problems and he reported to Boot Camp at Bainbridge, Maryland. Following boot camp he was ordered to Machinist Mate Class A School. After graduation he was assigned to the USS AULT (DD-698) and during this tour the ship made a ‘round the world cruise that concluded with duty off Korea. Completing his first sea tour he reported for shore duty with the Sherman Field Crash Crew at Pensacola, Florida. Then, back to sea aboard the USS ABBOT (DD-629), a Fletcher Class Destroyer that did not have an inboard Duane LeDoux and wife Jean did a run passageway to the forward engine room. -

Project Mercury Points the Way

Project Mercury Points the Way A rare primary recovery ship cover is shown for USS Noa’s recovery of Astronaut John Glenn from the Atlantic Ocean near Grand Bahama Island on his orbital flight, February 20, 1962. The USS Noa cover with PM in the postmark is one of the most difficult recovery ship covers to find for space cover collectors. by Steve Durst Copyright © 2008 by Steve Durst, all rights reserved. Preface I grew up in the early days of the development of America’s space program as Project Mercury unfolded like a serial show in the local movie theater with both incredible failures and stunning successes. For those of us who grew up in this period, the space program seemed magical. The thought that we could launch rockets into space to give us a new perspective of what the earth looked like, that a new breed of hero, the Astronaut, could capture the attention and imagination of all of us, and that these Astronauts would want to blast off into space on a rocket in a spacecraft was incredible. The determination and can- do ability of these military test pilots, scientists, engineers, and visionaries, men and women alike, still hold my utmost respect and admiration. Many people assisted me in putting this study together including fellow space history buffs and my core group of space cover collectors, including: Tom Steiner, President of the American Philatelic and American Topical Association’s Space Unit; Dr. Ben Ramkissoon, President Emeritus and Past President of the Space Unit; Dennis Dillman, member of the Space Unit and correspondent for the Astrophile journal; and Dr. -

Cipriano Griego US Navy USS Richard E Crouse Vietnam Interview Recorded September 11, 2014

Cipriano Griego US Navy USS Richard E Crouse Vietnam Interview recorded September 11, 2014 A: My name is Cipriano Griego. I was born in Albuquerque, New Mexico on December 5th, 1944. I lived in Albuquerque, New Mexico for the first 17 years of my life. I went to Lew Wallace Elementary School, I went to Washington Junior High and I graduated from Albuquerque High School. I was born in the Valley. If anyone knows about Albuquerque, there’s a valley and then there’s a heights. My family’s Hispanic. In those days, we call it Mexican-American. We – my dad was a contractor. He built homes. He built various kinds of things. My mother was mostly a stay-at-home mom but she did clean. She cleaned people’s houses. When I was younger, I remembered that she cleaned one lady’s house whose husband was an attorney which later on made me think about that profession. And a very interesting wife. When I was young, we – our family was normal extended family which means that my father had, I believe, eight brothers and sisters plus himself. My mother had seven brothers and sisters plus herself. Her mother raised her. Her dad was killed at a young age. He was in an accident. He worked for the railroad and was killed then. My father’s family, my uncles and aunts are very close, always having functions together as well as having so many children around when I was young. Every time we had an event, there was always kids around and we would always celebrate different kinds of events.