Youth Paper Sanni

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

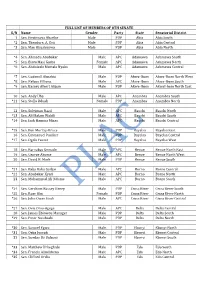

Full List of Members of the 8Th Senate

FULL LIST OF MEMBERS OF 8TH SENATE S/N Name Gender Party State Senatorial District 1 Sen. Enyinnaya Abaribe Male PDP Abia Abia South *2 Sen. Theodore. A. Orji Male PDP Abia Abia Central *3 Sen. Mao Ohuabunwa Male PDP Abia Abia North *4 Sen. Ahmadu Abubakar Male APC Adamawa Adamawa South *5 Sen. Binta Masi Garba Female APC Adamawa Adamawa North *6 Sen. Abdulaziz Murtala Nyako Male APC Adamawa Adamawa Central *7 Sen. Godswill Akpabio Male PDP Akwa-Ibom Akwa-Ibom North West *8 Sen. Nelson Effiong Male APC Akwa-Ibom Akwa-Ibom South *9 Sen. Bassey Albert Akpan Male PDP Akwa-Ibom AkwaI-bom North East 10 Sen. Andy Uba Male APC Anambra Anambra South *11 Sen. Stella Oduah Female PDP Anambra Anambra North 12 Sen. Suleiman Nazif Male APC Bauchi Bauchi North *13 Sen. Ali Malam Wakili Male APC Bauchi Bauchi South *14 Sen. Isah Hamma Misau Male APC Bauchi Bauchi Central *15 Sen. Ben Murray-Bruce Male PDP Bayelsa Bayelsa East 16 Sen. Emmanuel Paulker Male PDP Bayelsa Bayelsa Central *17 Sen. Ogola Foster Male PDP Bayelsa Bayelsa West 18 Sen. Barnabas Gemade Male APC Benue Benue North East 19 Sen. George Akume Male APC Benue Benue North West 20 Sen. David B. Mark Male PDP Benue Benue South *21 Sen. Baba Kaka Garbai Male APC Borno Borno Central *22 Sen. Abubakar Kyari Male APC Borno Borno North 23 Sen. Mohammed Ali Ndume Male APC Borno Borno South *24 Sen. Gershom Bassey Henry Male PDP Cross River Cross River South *25 Sen. Rose Oko Female PDP Cross River Cross River North *26 Sen. -

The Print Media As a Tool for Evangelisation in Auchi Diocese, Nigeria

Peter Eshioke Egielewa THE PRINT MEDIA AS A TOOL FOR EVANGELISATION IN AUCHI DIOCESE, NIGERIA: CONTEXTUALISATION AND CHALLENGES Table of Contents Table of Contents………………………………………………………………………...……..i Dedication……………………………………………………………………………………...x Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………..…..xi Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………….xii Chapter One GENERAL INTRODUCTION 1.0 Introduction………………………………………………………………………….…1 1.1 Why this study?...............................................................................................................1 1.2 Area of research………………………………………………………………………..8 1.3 Methodology……………………………………………………………………….…10 1.4 Organisation………………………………………………………………………..…11 1.5 Limitations of Study………………………………………………………………..…16 Part I Chapter Two CONTEXT: AUCHI DIOCESE v 2.0 Introduction……………………………………………………………………...……18 2.1 History……………………………………………………………………………...…18 2.2 Geography, Population and Peoples…………………………………………………..20 2.2.1 Auchi Weltanschauung (Worldview)……………………..…………………………..22 2.2.2 The Person in Auchi…………………………………………………………………..23 2.2.3 The Body……………………………………………………………………………...23 2.2.4 The Soul………………………………………………………………………………24 2.3 Religion……………………………………………………………………………….24 i 2.3.1 Auchi idea of God………………………………………………………………….…25 2.3.2 Monotheistic God of Auchi………………………………………………………...…26 2.3.3 Intermediaries…………………………………………………………………………27 2.3.3.1 Divinities and Spirits………………………………………………………………….27 2.3.3.2 Ancestors…………………………………………………………………………...…28 2.4 Social Life………………………………………………………………………….…29 2.4.1 The Individual……………………………………………………………………...…30 -

St. Patrick's College Maynooth the PROSPECTS of INTERFAITH

St. Patrick's College Maynooth THE PROSPECTS OF INTERFAITH DIALOGUE IN THE LIGHT AND TEACHINGS OF THE SECOND VATICAN COUNCIL: CONTEXTUAL IMPLICATIONS FOR CHRISTIANS AND MUSLIMS IN NIGERIA A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Theology in Partial Fulfilment of the Conditions for the Doctoral Degree in Theology By Yusuf Dominic Bamai Supervisor: Dr. Padraig Joseph Corkery Maynooth August 2019 TABLE OF CONTENT DEDICATION…………………………………………………………………………….x DECLARATION…………………………………………………………………………xi ACKNOWLEDGEMENT………………………………………………………………xii ABBREVIATIONS………………………………………………………………………xiv GENERAL INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………1 CHAPTER ONE CHALLENGES TO CHRISTIAN-MUSLIM DIALOGUE AND RELATIONS IN NIGERIA: SITUATING THE FACTORS RESPONSIBLE 1.1 Introduction……………………………………………………………………………5 1.2 Religion and the Nigerian State and Politics…………………………………………5 1.3 Cultural Diversity and Ethnicity in Nigeria: The Role of Religion……………….12 1.4 Religious Freedom and Equality in Nigeria………………………………………...17 1.5 Religious Discrimination in Nigeria…………………………………………………19 1.6 The Problem of Bribery and Corruption in Nigeria……………………………….25 1.7 Religious Insurgences/Terrorism and Fanaticisms in Nigeria…………………….27 1.7.1 Boko Haram Fanaticism and Insurgency …………………………………………...28 1.7.2 Herdsmen Activities of Terrorism in Nigeria……………………………………….33 1.8 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………36 CHAPTER TWO HISTORICAL BACKGROUND TO INTERFAITH DIALOGUE: PROMULGATION AND TEACHINGS OF NOSTRA AETATE AND VATICAN II ON INTERFAITH DIALOGUE SECTION A: HISTORICAL FOUNDATION 2.1 -

Boko Haram: Islamism, Politics, Security and the State in Nigeria

Boko Haram: Islamism, politics, security and the state in Nigeria African Studies Centre (ASC) Institut Français de Recherche en Afrique (IFRA) West African Politics and Society Series, Vol. 2 Boko Haram: Islamism, politics, security and the state in Nigeria Edited by Marc-Antoine Pérouse de Montclos Published by: African Studies Centre P.O. Box 9555 2300 RB Leiden [email protected] www.ascleiden.nl French Institute for Research in Africa / Institut Français de Recherche en Afrique (IFRA-Nigeria) University of Ibadan Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria www.ifra-nigeria.org Cover design: Heike Slingerland Printed by Ipskamp Drukkers, Enschede, Netherlands ISSN: 2213-5480 ISBN: 978-90-5448-135-5 © Marc-Antoine Pérouse de Montclos, 2014 Contents Figures and tables vii Foreword viii 1 INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW 1 Marc-Antoine Pérouse de Montclos PART I: WHAT IS BOKO HARAM? SOME EVIDENCE AND A LOT OF CONFUSION 2 THE MESSAGE AND METHODS OF BOKO HARAM 9 Kyari Mohammed 3 BOKO HARAM AND ITS MUSLIM CRITICS: OBSERVATIONS FROM YOBE STATE 33 Johannes Harnischfeger 4 TRADITIONAL QURANIC STUDENTS (ALMAJIRAI) IN NIGERIA: FAIR GAME FOR UNFAIR ACCUSATIONS? 63 Hannah Hoechner 5 CHRISTIAN PERCEPTIONS OF ISLAM AND SOCIETY IN RELATION TO BOKO HARAM AND RECENT EVENTS IN JOS AND NORTHERN NIGERIA 85 Henry Gyang Mang 6. FRAMING AND BLAMING: DISCOURSE ANALYSIS OF THE BOKO HARAM UPRISING, JULY 2009 110 Portia Roelofs PART II: B OKO HARAM AND THE NIGERIAN STATE: A STRATEGIC ANALYSIS 7. BOKO HARAM AND POLITICS: FROM INSURGENCY TO TERRORISM 135 Marc-Antoine Pérouse de Montclos 8. BOKO HARAM AND THE EVOLVING SALAFI JIHADIST THREAT IN NIGERIA 158 Freedom Onuoha v 9. -

Schedule of Activities for Ncs Recruitment Screening Exercise, 2021

NIGERIA CUSTOMS SERVICE HEADQUARTERS: Abidjan Street, Wuse, P.M.B. 26, Zone 3, Abuja – FCT Nigeria SCHEDULE OF ACTIVITIES FOR NCS RECRUITMENT SCREENING EXERCISE, 2021 In continuation of the Nigeria Customs Service recruitment process, the underlisted candidates are hereby invited to attend the final recruitment screening exercise. The candidates are required to report in batches to the venues assigned to their respective States of origin on dates indicated below. Superintendent Cadre (CONSOL 08) – 1st March 2021 Customs Inspector Cadre (CONSOL 06) – 3rd March, 2021 Customs Assistant Cadre (CONSOL 04) – 8th March, 2021 Customs Assistant Cadre (CONSOL 03) – 10TH March, 2021 ZONES AND VENUES Time North Wes t North East North Central South West South East/ (Customs (Tafawa Balewa (Customs (Customs South South Training College Stadium Bauchi) Command & Training College (Dan Anyiam Goron Dutse Staff College Ikeja Lagos) Stadium Kano) Gwagwalada) Owerri) 9am- 12:30pm Kaduna Adama wa Benu e Ekiti Abia Katsina Bauchi Kogi Lago s Enugu (BATCH A) Sokoto Gombe Nassarwa Oyo Ebonyi Zamfara Akwa-Ibo m Bayelsa Cross Rive r 2pm – 5pm Jigaw a Borno Kwara Ondo Anam bra Kano Tarab a Niger Ogun Imo (BATCH B) Kebbi Yobe Plateau Osun Delta FCT Edo Rivers GRADE LEVEL 08 50 NCS/C08/378671 ONYEBUCHI LESLIE OKOLI 1 NCS/C08/428192 BARILEERA INNOCENT SAM ACCOUNTS 51 NCS/C08/23396 KELVIN AMARI SAMAILA 2 NCS/C08/590468 CHIEMERIE OLIVIA ILOANUSI SN APPLICATION ID FIRST NAME MIDDLE NAME LAST NAME 52 NCS/C08/68645 AHMAD LAWAL IMAM 3 NCS/C08/165125 OMOLAYO ZAINAB AYODELE -

Update Your ROFO and Get Your COFO from NAGIS KARU L.G.A

KARU L.G.A. Update Your ROFO and get your COFO from NAGIS KARU L.G.A. Applicants ROFO Number and Name for Properties in KARU L.G.A. BP 659 / TIN AND ASSOCIATES MINERALS LTD NS 869 / MARYANNE OIZA ASUKU NS 2247 / VICTOR A ADEO YE NS 003 / JAMES AUDU EGGAH NS 870 / HENRY W. NIYO NS 2268 / JOSEPH DEMEW IGBETAR NS 008 / GODWIN NWACHUKWU NS 872 / EUGENE NNAEMEKA OKONGWU NS 2273 / THE REDEEMED CHRISTAIN CHURCH OF NS 010 / DAMIEN OBIAKOR NS 874 / BARDE GIDEON GOCEDAN GWIMBE GOD NS 022 / FELIX C. ANALOGBEI NS 877 / EDEM UDO UDO EKANEM NS 2301 / MOONEMAN TOM JAJA NS 023 / STEPHEN O. ETAFO NS 878 / GARBA Y. KONTAGORA NS 2335 / SULEIMAN ABBA NS 053 / DANLADI YARO NS 879 / JOSEPH I. ORJI NS 2336 / LAZARUS NEBECHUKWU NS 063 / SOLOMON Z. LABAFILO NS 880 / AMOS TOKAN WAMYIL NS 2349 / VERONIKA N. OTULE NS 093 / JAMES AUDU EGGAH NS 881 / AKILA FOMPUN NS 2353 / UGUOKE ANTHONY OKEKE NS 129 / O. T. MAJEKODUNMI NS 884 / NAHUM HARUNA ANGYU NS 2362 / AUTA WARAI IBRAHI M NS 136 / NIMVEN Z. MIRI NS 885 / OBADIAH DANLAMI ANDO NS 2363 / LAZARU NNEBECHUKWU NS 139 / LAWAN TIJANI K. NS 886 / ENGA EZEKEIL OBADIAH NS 2364 / E. BABAYO SHEHU NS 146 / VINCENT OSUNBOR NS 889 / OLAYINKA JOYCE MOWOE NS 2365 / IKIMIUKORO HELEN ISE NS 149 / YUSUF ANAS USMAN NS 927 / FIRST CAPITA L SAVING AND LOANS LTD NS 2366 / TUKUR NUHU NS 152 / CHRISTIANA EMMANUEL NS 968 / CLETUS UMERIE NS 2367 / IBRAHIM MUSA ASHAYA NS 161 / SILAS JARUMI DACHOR NS 1053 / AHAMED BALA NS 2368 / OHIKA JIBO NS 184 / RHODA DOY NS 1158 / BENJAMIN DURU IBE NS 2370 / IFEANYI ODEDO NS 192 / EMMANUEL ONONOGBU OGBONNAYA NS 1233 / BARNABAS NANPAK BONKAT NS 2372 / UKECHUKWU UKEJE NS 19 4 / LOHDAM NDAM NS 1242 / JUMBO OCHIGBO DESMOND NS 2380 / CLETUS NYIUTSA KYANDE NS 198 / AMADASUN OSAMWENYOBO NS 1263 / ALBERT EKEH NS 2 384 / ERIC NNAEMEKA ONAH NS 302 / OMOJOLA SAMUEL OMONIYI NS 1265 / ZIRA SUNDAY NS 2387 / EMMANUEL OGBANJE O. -

Boko Haram: Islamism, Politics, Security and the State in Nigeria

Boko Haram: Islamism, politics, security and the state in Nigeria African Studies Centre (ASC) Institut Français de Recherche en Afrique (IFRA) West African Politics and Society Series, Vol. 2 Boko Haram: Islamism, politics, security and the state in Nigeria Edited by Marc-Antoine Pérouse de Montclos Published by: African Studies Centre P.O. Box 9555 2300 RB Leiden [email protected] www.ascleiden.nl French Institute for Research in Africa / Institut Français de Recherche en Afrique (IFRA-Nigeria) University of Ibadan Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria www.ifra-nigeria.org Cover design: Heike Slingerland Printed by Ipskamp Drukkers, Enschede, Netherlands ISSN: 2213-5480 ISBN: 978-90-5448-135-5 © Marc-Antoine Pérouse de Montclos, 2014 Contents Figures and tables vii Foreword viii 1 INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW 1 Marc-Antoine Pérouse de Montclos PART I: WHAT IS BOKO HARAM? SOME EVIDENCE AND A LOT OF CONFUSION 2 THE MESSAGE AND METHODS OF BOKO HARAM 9 Kyari Mohammed 3 BOKO HARAM AND ITS MUSLIM CRITICS: OBSERVATIONS FROM YOBE STATE 33 Johannes Harnischfeger 4 TRADITIONAL QURANIC STUDENTS (ALMAJIRAI) IN NIGERIA: FAIR GAME FOR UNFAIR ACCUSATIONS? 63 Hannah Hoechner 5 CHRISTIAN PERCEPTIONS OF ISLAM AND SOCIETY IN RELATION TO BOKO HARAM AND RECENT EVENTS IN JOS AND NORTHERN NIGERIA 85 Henry Gyang Mang 6. FRAMING AND BLAMING: DISCOURSE ANALYSIS OF THE BOKO HARAM UPRISING, JULY 2009 110 Portia Roelofs PART II: B OKO HARAM AND THE NIGERIAN STATE: A STRATEGIC ANALYSIS 7. BOKO HARAM AND POLITICS: FROM INSURGENCY TO TERRORISM 135 Marc-Antoine Pérouse de Montclos 8. BOKO HARAM AND THE EVOLVING SALAFI JIHADIST THREAT IN NIGERIA 158 Freedom Onuoha v 9. -

Boko Haram and Politics : from Insurgency to Terrorism

7 Boko Haram and politics: From insurgency to terrorism Marc-Antoine Pérouse de Montclos Abstract Based on the case of Boko Haram, or Jama’atu Ahlis-Sunnah Lidda’awati Wal Jihad (“People Committed to the Propagation of the Prophet’s Teachings and Jihad”) to give it its real name, this chapter introduces a general discussion on the relationship between Islam and politics in Nigeria. Unlike Hamas in Pales- tine, Hezbollah in Lebanon, or the Muslim Brothers in Egypt, Boko Haram is neither a political party nor a charity network. It is political because it contests Western values, challenges the secularity of the Nigerian state, and reveals the corruption of a “democrazy” that relies on a predatory ruling elite, the so-called “godfathers”. But Boko Haram also remains a sect, now engaged in terrorist violence. From Mohammed Yusuf to Abubakar Shekau, its leaders have never actually proposed a political programme to reform and govern Nigeria accord- ing to Shariah. In this regard, Boko Haram raises an important question: why has Nigeria never had a religious political party, either Islamic or Christian? Federalism and the alleged ‘neutrality’ of military regimes do not explain eve- rything. Compared with the situation in Northern Sudan, the structure and divi- sion of Islam also help us to understand why Nigerian Muslims have never succeeded in setting up a political platform to contest elections with a religious programme, and why violence became an alternative channel for reform. Introduction The Western media and many Nigerians see the terrorist attacks of Boko Haram as part of a wider global religious war between Muslims and Christians. -

CORI Thematic Report Nigeria: Gender and Age December 2012

Confirms CORI country of origin research and information CORI Thematic Report Nigeria: Gender and Age December 2012 Commissioned by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Division of International Protection. Any views expressed in this paper are those of the author and are not necessarily those of UNHCR. CORI Thematic Report, Nigeria: Gender and Age, December 2012 Preface Country of Origin Information (COI) is required within Refugee Status Determination (RSD) to provide objective evidence on conditions in refugee producing countries to support decision making. Quality information about human rights, legal provisions, politics, culture, society, religion and healthcare in countries of origin is essential in establishing whether or not a person’s fear of persecution is well founded. CORI Country Reports are designed to aid decision making within RSD. They are not intended to be general reports on human rights conditions. They serve a specific purpose, collating legally relevant information on conditions in countries of origin, pertinent to the assessment of claims for asylum. Categories of COI included within this report are based on the most common issues arising from asylum applications made on the basis of gender and age by Nigerian nationals. This report covers events up to 10 December 2012. COI is a specific discipline distinct from academic, journalistic or policy writing, with its own conventions and protocols of professional standards as outlined in international guidance such as The Common EU Guidelines on Processing Country of Origin Information, 2008 and UNHCR, Country of Origin Information: Towards Enhanced International Cooperation, 2004. CORI provides information impartially and objectively, the inclusion of source material in this report does not equate to CORI agreeing with its content or reflect CORI’s position on conditions in a country. -

SHSH Commentary on the December 2013 Nigeria

THIS DOCUMENT SHOULD BE USED AS A TOOL FOR IDENTIFYING RELEVANT COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION. IT SHOULD NOT BE SUBMITTED AS EVIDENCE TO THE HOME OFFICE, THE TRIBUNAL OR OTHER DECISION MAKERS IN ASYLUM APPLICATIONS OR APPEALS © Still Human Still Here 2013 13th December 2013 A Commentary on the December 2013 Nigeria Operational Guidance Note This commentary identifies what the ‘Still Human Still Here’ coalition considers to be the main inconsistencies and omissions between the currently available country of origin information (COI) and case law on Nigeria and the conclusions reached in the December 2013 Nigeria Operational Guidance Note (OGN) issued by the UK Home Office. Where we believe inconsistencies have been identified, the relevant section of the OGN is highlighted in blue. An index of full sources of the COI referred to in this commentary is also provided at the end of the document. This commentary is a guide for legal practitioners and decision-makers in respect of the relevant COI, by reference to the sections of the Operational Guidance Note on Nigeria issued in December 2013. Access the complete OGN on Nigeria here. The document should be used as a tool to help to identify relevant COI and the COI referred to can be considered by decision makers in assessing asylum applications and appeals. This document should not be submitted as evidence to the UK Home Office, the Tribunal or other decision makers in asylum applications or appeals. However, legal representatives are welcome to submit the COI referred to in this document to decision makers (including Judges) to help in the accurate determination of an asylum claim or appeal. -

Teachers Registration Council of Nigeria, Headquarters, Abuja Professional Qualifying Examination October Diet 2018 List of Successful Candidates

TEACHERS REGISTRATION COUNCIL OF NIGERIA, HEADQUARTERS, ABUJA PROFESSIONAL QUALIFYING EXAMINATION OCTOBER DIET 2018 LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES ABIA STATE S/N NAME PQE NUMBER CAT 1 ORLU EGEONU SUCCESS AB/PQE/B018/R/00010 D 2 UDE OLA IKPA AB/PQE/B018/S/00004 D 3 NJOKU CHINYERE CALISTA AB/PQE/B018/R/00003 C 4 ELECHI MESOMA OKORONKWO AB/PQE/B018/R/00012 D 5 IFEGWU CATHERINE OLAMMA AB/PQE/B018/P/00002 D 6 NWAZUBA MARYROSE CHINENYE AB/PQE/B018/S/00010 D 7 UMEH EMMANUEL CHIMA AB/PQE/B018/R/00006 D 8 OKEKE JOY KALU AB/PQE/B018/P/00056 D 9 NWACHUKWU IFEANYI AB/PQE/B018/T/00001 B 10 NWAGBARA CHRISTIAN KELECHI AB/PQE/B018/S/00009 C 11 EKE KALU ELEKWA AB/PQE/B018/P/00004 C 12 AMANYIE LENEBARI DARLINGTON AB/PQE/B018/R/00039 D 13 ONWUKAEME MERCY CHINAGORO AB/PQE/B018/R/00037 D 14 UZOMAKA JOY CHIBUZO AB/PQE/B018/R/00009 D 15 KALU GLORY OGBU AB/PQE/B018/P/00030 D 16 UGBOR REJOICE AB/PQE/B018/S/00015 C 17 MADUKWE KOSARACHI WISDOM AB/PQE/B018/R/00001 C 18 DIBIA OGECHI MODESTA AB/PQE/B018/S/00016 C 19 ELECHI PATIENCE ADA AB/PQE/B018/R/00016 D 20 UGWU CALISTUS TOBECHUKWU AB/PQE/B018/R/00022 D 21 OKALI ONYINYECHI NJOKU AB/PQE/B018/R/00026 D 22 NWOSU ONYINYECHI PRISCILIA AB/PQE/B018/P/00046 D 23 OHAJURU KEZIAH NKEIRU AB/PQE/B018/P/00038 C 24 IZUWA NNEAMAKA IJEOMA AB/PQE/B018/S/00014 C 25 UKWEN ROSEMARY OLE AB/PQE/B018/P/00001 C 26 COLLINS MICHAEL UGOCHUKWU AB/PQE/B018/P/00057 D 27 ASSIAN UKEME EDET AB/PQE/B018/R/00018 D 28 EYET JAMES JAMES AB/PQE/B018/R/00023 D 29 IGBOAMAGH ONUOHA AMARACHI AB/PQE/B018/R/00007 D 30 OHIA JULIET UCHENNA AB/PQE/B018/P/00014 -

Christian Muslim Digest

Network for Inter faith Concerns Christian-Muslim News Digest Issue 2 2009 Christian-Muslim News Digest Introduction Welcome to the second issue of the Digest for 2009. This issue looks at Christians and Identity Cards in Egypt, the call for the expansion of Shari‘ah in Nigeria, a report by the Quilliam Foundation on the training of Imams in the UK, a meeting of Iraqi church leaders, a women’s interfaith initiative in Indonesia, and, in depth, at the situation in Pakistan. The article Identity and Basic Rights: Pakistani Christians’ Perspective is by Revd. Rana Youab Khan, who is the Advisor to the Bishop on Interfaith Relations, Lahore Diocese, Church of Pakistan. Egypt: Religious Classification on Identity Cards In March The Guardian reported on a ruling concerning Identity Cards ‘Egypt’s step towards freedom of belief’. It explained that a court ruling meant that Egyptians will no longer be forced to identify themselves as belonging to one of three approved religions. It described this as a crucial victory for equal rights. The court ruled on a case brought by a Baha’i who was able to successfully demonstrate that he belonged to none of the three religions that are permitted on ID cards; he is now allowed to leave blank the ‘religion’ section on his National ID card. The practice of restricting religion on ID cards began in 1995, when the Egyptian government began introducing computerised ID cards which required everyone to identify themselves as belonging to one of the three ‘heavenly’ religions: Islam, Christianity or Judaism. Cards could not be issued to anyone who refused to accept this, with the result that they effectively became non-citizens.