SHSH Commentary on the December 2013 Nigeria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nigeria: Vigilante Violence in the South and South-East

TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION: Government responsibility in vigilante violence .................................. 1 2. VIGILANTE PHENOMENON IN NIGERIA:.................................................................... 3 2.1. Traditional concept of vigilante groups in Nigeria .................................................... 3 2.2. Vigilante groups today .................................................................................................. 3 2.3. Endorsement of armed vigilante groups by state governments ................................ 5 3. OFFICIAL ENDORSEMENT OF ARMED VIGILANTE GROUPS IN THE SOUTH- EAST: THE BAKASSI BOYS ........................................................................................ 6 3.1. Anambra State Vigilante Service (AVS) ..................................................................... 7 3.2. Abia State Vigilante Service (AVS) ........................................................................... 12 3.3. Imo State Vigilante Service (IVS) .............................................................................. 13 3.4. Other vigilante groups in the south ........................................................................... 14 3.4.1. Ethnic armed vigilante groups................................................................................ 14 3.4.2. The O’odua Peoples Congress (OPC) .................................................................... 16 4. VIGILANTE VIOLENCE IN VIEW OF FORTHCOMING ELECTIONS ...................... 17 5. CONCLUSION ................................................................................................................... -

Juju and Justice at the Movies: Vigilantes in Nigerian Popular Videos John C

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OpenSIUC Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Publications Department of Anthropology 12-2004 Juju and Justice at the Movies: Vigilantes in Nigerian Popular Videos John C. McCall Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/anthro_pubs Recommended Citation McCall, John C. "Juju and Justice at the Movies: Vigilantes in Nigerian Popular Videos." African Studies Review 47, No. 3 (Dec 2004): 51-67. doi:10.1017/S0002020600030444. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Anthropology at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This article was published as: Juju and Justice at the Movies: Vigilantes in Nigerian Popular Videos. African Studies Review, Vol. 47, No. 3 (Dec., 2004), pp. 51-67. Juju and Justice at the Movies: Vigilantes in Nigerian Popular Videos John C. McCall Associate Professor of Anthropology Mailcode 4502 Southern Illinois University Carbondale, IL 62901-4502 618-453-5010 [email protected] Acknowledgements This research was made possible by a Fulbright-Hays Faculty Research Abroad Fellowship (2002), a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities (2000), and a Southern Illinois University Summer Fellowship (2000). I am grateful to the many Nigerians who assisted me in this project. Special recognition must be given to Kabat Esosa Egbon, Anayo Enechukwu, the late Victor Nwankwo, and Ibe Nwosu Kalu. I am especially grateful to my friend and colleague Christey Carwile who assisted in many aspects of this research. -

Boko Haram Beyond the Headlines: Analyses of Africa’S Enduring Insurgency

Boko Haram Beyond the Headlines: Analyses of Africa’s Enduring Insurgency Editor: Jacob Zenn Boko Haram Beyond the Headlines: Analyses of Africa’s Enduring Insurgency Jacob Zenn (Editor) Abdulbasit Kassim Elizabeth Pearson Atta Barkindo Idayat Hassan Zacharias Pieri Omar Mahmoud Combating Terrorism Center at West Point United States Military Academy www.ctc.usma.edu The views expressed in this report are the authors’ and do not necessarily reflect those of the Combating Terrorism Center, United States Military Academy, Department of Defense, or U.S. Government. May 2018 Cover Photo: A group of Boko Haram fighters line up in this still taken from a propaganda video dated March 31, 2016. COMBATING TERRORISM CENTER ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Director The editor thanks colleagues at the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point (CTC), all of whom supported this endeavor by proposing the idea to carry out a LTC Bryan Price, Ph.D. report on Boko Haram and working with the editor and contributors to see the Deputy Director project to its rightful end. In this regard, I thank especially Brian Dodwell, Dan- iel Milton, Jason Warner, Kristina Hummel, and Larisa Baste, who all directly Brian Dodwell collaborated on the report. I also thank the two peer reviewers, Brandon Kend- hammer and Matthew Page, for their input and valuable feedback without which Research Director we could not have completed this project up to such a high standard. There were Dr. Daniel Milton numerous other leaders and experts at the CTC who assisted with this project behind-the-scenes, and I thank them, too. Distinguished Chair Most importantly, we would like to dedicate this volume to all those whose lives LTG (Ret) Dell Dailey have been afected by conflict and to those who have devoted their lives to seeking Class of 1987 Senior Fellow peace and justice. -

Vigilante in South-Western Nigeria Laurent Fourchard

A new name for an old practice: vigilante in South-western Nigeria Laurent Fourchard To cite this version: Laurent Fourchard. A new name for an old practice: vigilante in South-western Nigeria. Africa, Cambridge University Press (CUP), 2008, 78 (1), pp.16-40. hal-00629061 HAL Id: hal-00629061 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00629061 Submitted on 5 Oct 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. A new name for an old practice: vigilante in South-western Nigeria By Laurent Fourchard, Fondation Nationale des Sciences Politiques, Centre d’Etude d’Afrique Noire, Bordeaux1 “We keep learning strange names such as vigilante for something traditional but vigilante has been long here. I told you, I did it when I was young”. Alhadji Alimi Buraimo Bello, 85 years, Ibadan, January 2003. Since the 1980s, the phenomenon of vigilante and vigilantism have been widely studied through an analysis of the rise of crime and insecurity, the involvement of local groups in political conflicts and in a more general framework of a possible decline of law enforcement state agencies. Despite the fact that vigilante and vigilantism have acquired a renewed interest especially in the African literature, Michael L. -

Vigilante Groups and Policing in a Democratizing Nigeria: Navigating the Context and Issues

Brazilian Journal of African Studies | Porto Alegre | v. 4, n. 8, Jul./Dec. 2019 | p. 179-199 179 VIGILANTE GROUPS AND POLICING IN A DEMOCRATIZING NIGERIA: NAVIGATING THE CONTEXT AND ISSUES Adeniyi S. Basiru1 Olusesan A. Osunkoya2 Introduction Before the advent of colonialism in Nigeria, the various indigenous communities, like elsewhere in Africa, had evolved various self-help institu- tions (vigilante groups in modern sense) for maintaining public order. But, with the emergence of the colonial state and all its coercive paraphernalia, these traditional institutions of public order management, that had for cen- turies served the people, were relegated to the background, as the modern police force, the precursor of the present day Nigerian Police, under the direction of the colonial authorities, became the primus inter pares, in the internal security architecture of the colony (Ahire, 1991, 18). With this deve- lopment, the communal/collectivist-oriented frameworks of policing that had for centuries been part of people’s social existence now constituted the informal models of policing rendering subsidiary roles. For decades, this was the arrangement for policing the vast Nigerian territory. Although, there were documented cases of police re-organizations, by the colonial authorities, in Lagos, in 1930 and 1954 (Akuul, 2011, 18), these, however, neither reversed the western-dominated order of policing nor re-organized the indigenous informal models of policing. Put differently, the indigenous police institutions, in differently parts of the country, continued to play subsidiary roles in public order management. Instructively, at inde- pendence, the colonial arrangement rather than being transformed to reflect 1 Department of Political Science, University of Lagos, Lagos, Nigeria. -

Corruption in Civil Society Activism in the Niger Delta and Defines Csos to Include Ngos, Self-Help Groups and Militant Organisations

THE ROLE OF CORRUPTION ON CIVIL SOCIETY ACTIVISM IN THE NIGER DELTA BY TOMONIDIEOKUMA BRIGHT A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE LANCASTER UNIVERSITY FOR DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY SUBMISSION DATE: SEPTEMBER, 2019 i Abstract: This thesis studies the challenges and relationships between the Niger delta people, the federal government and Multinational Oil Companies (MNOCs). It describes the major problems caused by unmonitored crude oil exploitation as environmental degradation and underdevelopment. The study highlights the array of roles played by Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) in filling the gap between the stakeholders in the oil industry and crude oil host communities. Except for the contributions from Austin Ikelegbe (2001), Okechukwu Ibeanu (2006) and Shola Omotola (2009), there is a limitation in the literature on corruption and civil society activism in the Niger delta. These authors dwelt on the role of CSOs in the region’s struggle. But this research fills a knowledge gap on the role of corruption in civil society activism in the Niger delta and defines CSOs to include NGOs, self-help groups and militant organisations. Corruption is problematic in Nigeria and affects every sector of the economy including CSOs. The corruption in CSOs is demonstrated in their relationship with MNOCs, the federal government, host communities and donor organisations. Smith (2010) discussed the corruption in NGOs in Nigeria which is also different because this work focuses on the role of corruption in CSOs in the Niger delta and the problems around crude oil exploitation. The findings from the fieldwork using oral history, ethnography, structured and semi-structured interview methods show that corruption impacts CSOs activism in diverse ways and has structural and historical roots embedded in colonialism. -

Boko Haram Beyond the Headlines: Analyses of Africa’S Enduring Insurgency

Boko Haram Beyond the Headlines: Analyses of Africa’s Enduring Insurgency Editor: Jacob Zenn HASSAN / PIERI BOKO HARAM BEYOND THE HEADLINES MAY 2018 CHAPTER 4: The Rise and Risks of Nigeria’s Civilian Joint Task Force: Implications for Post-Conflict Recovery in Northeastern Nigeria By Idayat Hassan and Zacharias Pieri Introduction Since 2009, the violent activities of the jihadi group popularly known as Boko Haram have caused major upheaval and insecurity in Nigeria and the neighboring Lake Chad Basin (LCB) countries. The escalation of violence in 2013 culminated with a state of emergency being announced in the northeast- ern region of Nigeria, but the situation did not improve. Boko Haram continued to expand, declaring a so-called caliphate in 2014 and initiating in the next year a pledge of allegiance to the Islamic State.418 By November 2014, the deputy governor of Borno State commented that if Boko Haram continued at its current pace, it would only be a short time before “the three northeastern states will no longer be in existence.”419 Such predictions did not come true. A multinational force including Chadian and Nigerien troops to support Nigerian troops in Borno broke Boko Haram’s momentum in the run-up to Nigeria’s presi- dential elections in February 2015, and since then, Boko Haram has lost the majority of its territory, though not its operational capacity.420 While many studies focus on the state response to the conflict, the aim of this article is to consider the response of non-state actors, and in particular communi- ty-based armed groups (CBAGs), to Boko Haram. -

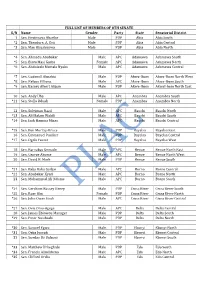

Full List of Members of the 8Th Senate

FULL LIST OF MEMBERS OF 8TH SENATE S/N Name Gender Party State Senatorial District 1 Sen. Enyinnaya Abaribe Male PDP Abia Abia South *2 Sen. Theodore. A. Orji Male PDP Abia Abia Central *3 Sen. Mao Ohuabunwa Male PDP Abia Abia North *4 Sen. Ahmadu Abubakar Male APC Adamawa Adamawa South *5 Sen. Binta Masi Garba Female APC Adamawa Adamawa North *6 Sen. Abdulaziz Murtala Nyako Male APC Adamawa Adamawa Central *7 Sen. Godswill Akpabio Male PDP Akwa-Ibom Akwa-Ibom North West *8 Sen. Nelson Effiong Male APC Akwa-Ibom Akwa-Ibom South *9 Sen. Bassey Albert Akpan Male PDP Akwa-Ibom AkwaI-bom North East 10 Sen. Andy Uba Male APC Anambra Anambra South *11 Sen. Stella Oduah Female PDP Anambra Anambra North 12 Sen. Suleiman Nazif Male APC Bauchi Bauchi North *13 Sen. Ali Malam Wakili Male APC Bauchi Bauchi South *14 Sen. Isah Hamma Misau Male APC Bauchi Bauchi Central *15 Sen. Ben Murray-Bruce Male PDP Bayelsa Bayelsa East 16 Sen. Emmanuel Paulker Male PDP Bayelsa Bayelsa Central *17 Sen. Ogola Foster Male PDP Bayelsa Bayelsa West 18 Sen. Barnabas Gemade Male APC Benue Benue North East 19 Sen. George Akume Male APC Benue Benue North West 20 Sen. David B. Mark Male PDP Benue Benue South *21 Sen. Baba Kaka Garbai Male APC Borno Borno Central *22 Sen. Abubakar Kyari Male APC Borno Borno North 23 Sen. Mohammed Ali Ndume Male APC Borno Borno South *24 Sen. Gershom Bassey Henry Male PDP Cross River Cross River South *25 Sen. Rose Oko Female PDP Cross River Cross River North *26 Sen. -

Journal of International and Global Studies 5(2)

“States of Emergency”: Armed Youths and Mediations of Islam in Northern Nigeria Conerly Casey PhD Rochester Institute of Technology [email protected] Abstract On November 14, 2013, the U.S. Department of State labeled Boko Haram and a splinter group, Ansaru, operating in northern Nigeria, “foreign terrorist organizations” with links to al-Qa’ida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM). This designation is debatable, since the groups are diffuse, with tendencies to split or engage other armed groups into violent actions, primarily focused on Nigerian national and state politics and the implementation of shari’a criminal codes. This essay offers two analytic perspectives on “states of emergency” in Nigeria and the affective, violent forms of “justice” that armed young men employed during the 2000 implementation of shari’a criminal codes in Kano State, important contexts for analyses of militant groups such as Boko Haram or Ansaru. One analysis is meant to capture the expressive aspects of justice, and the other presumes a-priori realms of public experience and understanding that mediate the suffering and the cultural, religious, and political forms of justice Muslim youths draw upon to make sense of their plight. Based on eight years of ethnographic research in northern Nigeria, I suggest the uneasy reliance in Nigeria on secular and religious legalism as well as on extrajudicial violence to assure “justice” (re)enacts real-virtual experiences of authorized violence as “justice” in Nigeria’s heavily mediated publics. Journal of International and Global Studies Volume 5, Number 2 2 On November 14, 2013, the U.S. Department of State labeled Boko Haram and a splinter group, Ansaru, operating in northern Nigeria, “foreign terrorist organizations” with links to al- Qa’ida in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM). -

The Print Media As a Tool for Evangelisation in Auchi Diocese, Nigeria

Peter Eshioke Egielewa THE PRINT MEDIA AS A TOOL FOR EVANGELISATION IN AUCHI DIOCESE, NIGERIA: CONTEXTUALISATION AND CHALLENGES Table of Contents Table of Contents………………………………………………………………………...……..i Dedication……………………………………………………………………………………...x Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………………..…..xi Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………….xii Chapter One GENERAL INTRODUCTION 1.0 Introduction………………………………………………………………………….…1 1.1 Why this study?...............................................................................................................1 1.2 Area of research………………………………………………………………………..8 1.3 Methodology……………………………………………………………………….…10 1.4 Organisation………………………………………………………………………..…11 1.5 Limitations of Study………………………………………………………………..…16 Part I Chapter Two CONTEXT: AUCHI DIOCESE v 2.0 Introduction……………………………………………………………………...……18 2.1 History……………………………………………………………………………...…18 2.2 Geography, Population and Peoples…………………………………………………..20 2.2.1 Auchi Weltanschauung (Worldview)……………………..…………………………..22 2.2.2 The Person in Auchi…………………………………………………………………..23 2.2.3 The Body……………………………………………………………………………...23 2.2.4 The Soul………………………………………………………………………………24 2.3 Religion……………………………………………………………………………….24 i 2.3.1 Auchi idea of God………………………………………………………………….…25 2.3.2 Monotheistic God of Auchi………………………………………………………...…26 2.3.3 Intermediaries…………………………………………………………………………27 2.3.3.1 Divinities and Spirits………………………………………………………………….27 2.3.3.2 Ancestors…………………………………………………………………………...…28 2.4 Social Life………………………………………………………………………….…29 2.4.1 The Individual……………………………………………………………………...…30 -

Situation Sécuritaire Dans Le Delta Du Niger NIGERIA

NIGERIA 18 mai 2018 Situation sécuritaire dans le delta du Niger Les facteurs du conflit et ses conséquences pour les communautés locales ; les principaux groupes armés opérant dans la région ; les activités criminelles et modes de recrutement de ces groupes. Avertissement Ce document a été élaboré par la Division de l’Information, de la Documentation et des Recherches de l’Ofpra en vue de fournir des informations utiles à l’examen des demandes de protection internationale. Il ne prétend pas faire le traitement exhaustif de la problématique, ni apporter de preuves concluantes quant au fondement d’une demande de protection internationale particulière. Il ne doit pas être considéré comme une position officielle de l’Ofpra ou des autorités françaises. Ce document, rédigé conformément aux lignes directrices communes à l’Union européenne pour le traitement de l’information sur le pays d’origine (avril 2008) [cf. https://www.ofpra.gouv.fr/sites/default/files/atoms/files/lignes_directrices_europeennes.pdf ], se veut impartial et se fonde principalement sur des renseignements puisés dans des sources qui sont à la disposition du public. Toutes les sources utilisées sont référencées. Elles ont été sélectionnées avec un souci constant de recouper les informations. Le fait qu’un événement, une personne ou une organisation déterminée ne soit pas mentionné(e) dans la présente production ne préjuge pas de son inexistence. La reproduction ou diffusion du document n’est pas autorisée, à l’exception d’un usage personnel, sauf accord de l’Ofpra en vertu de l’article L. 335-3 du code de la propriété intellectuelle. Situation sécuritaire dans le delta du Niger Table des matières 1. -

Insurgency and National Security Challenges in Nigeria: Looking Back, Looking Ahead

Insurgency and National Security Challenges in Nigeria: Looking Back, Looking Ahead Sheriff F. Folarin, PhD Associate Professor Department of Political Science and International Relations Covenant University, Ota, Nigeria [email protected] and Faith O. Oviasogie Lecturer Department of Political Science and International Relations Covenant University, Ota, Nigeria [email protected] Abstract The 1648 Treaty of Westphalia designed a state system on the twin-principle of territoriality and sovereignty. Sovereignty accords the state unquestionable but legitimate control over the nation and polity, and gives it the latitude to preserve and protect its territorial domain from both internal and external threats. However, aside the fact that globalisation and the internationalisation of the globe have reduced the primacy of these dual principles, there have also been the problem of ideological and terrorist networks that have taken advantage of the instruments of globalization to emerge and threaten state sovereignty and its preservation. The security and sovereignty of the Nigerian State have been under threat as a result of the emergence and activities of insurgent groups, such as Boko Haram in the Northeast and other militant groups in other parts of the country. Using a descriptive-analytical approach, this paper examines the security challenges Nigeria faces from insurgency and the impact of this on national peace, security and sovereignty. The study shows that the frequency of insurgent attacks has resulted in collateral damage on the peace, stability, development and sovereignty of the state. It finds also that the federal government has not been decisive enough. These place urgent and decisive demand on the government to adopt new management strategy that will address and contain the insurgent and terrorist groups.