Ent. Tidskr. 140 (2019)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Phthiraptera: Ischnocera), with an Overview of the Geographical Distribution of Chewing Lice Parasitizing Chicken

European Journal of Taxonomy 685: 1–36 ISSN 2118-9773 https://doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2020.685 www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu 2020 · Gustafsson D.R. & Zou F. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0). Research article urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:151B5FE7-614C-459C-8632-F8AC8E248F72 Gallancyra gen. nov. (Phthiraptera: Ischnocera), with an overview of the geographical distribution of chewing lice parasitizing chicken Daniel R. GUSTAFSSON 1,* & Fasheng ZOU 2 1 Institute of Applied Biological Resources, Xingang West Road 105, Haizhu District, Guangzhou, 510260, Guangdong, China. 2 Guangdong Key Laboratory of Animal Conservation and Resource Utilization, Guangdong Public Laboratory of Wild Animal Conservation and Utilization, Guangdong, China. * Corresponding author: [email protected] 2 Email: [email protected] 1 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:8D918E7D-07D5-49F4-A8D2-85682F00200C 2 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:A0E4F4A7-CF40-4524-AAAE-60D0AD845479 Abstract. The geographical range of the typically host-specific species of chewing lice (Phthiraptera) is often assumed to be similar to that of their hosts. We tested this assumption by reviewing the published records of twelve species of chewing lice parasitizing wild and domestic chicken, one of few bird species that occurs globally. We found that of the twelve species reviewed, eight appear to occur throughout the range of the host. This includes all the species considered to be native to wild chicken, except Oxylipeurus dentatus (Sugimoto, 1934). This species has only been reported from the native range of wild chicken in Southeast Asia and from parts of Central America and the Caribbean, where the host is introduced. -

Examensarbete Institutionen För Ekologi Lynx Behaviour Around

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Epsilon Archive for Student Projects Examensarbete Institutionen för ekologi Lynx behaviour around reindeer carcasses Håkan Falk INDEPENDENT PROJECT, BIOLOGY LEVEL D, 30 HP SUPERVISOR: JENNY MATTISSON, DEPT OF ECOLOGY, GRIMSÖ WILDLIFE RESEARCH STATION COSUPERVISOR: HENRIK ANDRÉN, DEPT OF ECOLOGY, GRIMSÖ WILDLIFE RESEARCH STATION EXAMINER: JENS PERSSON, DEPT OF ECOLOGY, GRIMSÖ WILDLIFE RESEARCH STATION Examensarbete 2009:14 Grimsö 2009 SLU, Institutionen för ekologi Grimsö forskningsstation 730 91 Riddarhyttan 1 SLU, Sveriges lantbruksuniversitet/Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences NL-fakulteten, Fakulteten för naturresurser och lantbruk/Faculty of Natural Resources and Agricultural Sciences Institutionen för ekologi/Department of Ecology Grimsö forskningsstation/Grimsö Wildlife Research Station Författare/Author: Håkan Falk Arbetets titel/Title of the project: Lynx behaviour around reindeer carcasses Titel på svenska/Title in Swedish: Lodjurs beteende vid renkadaver Nyckelord/Key words: Lynx, reindeer, wolverine, predation, scavenging Handledare/Supervisor: Jenny Mattisson, Henrik Andrén Examinator/Examiner: Jens Persson Kurstitel/Title of the course: Självständigt arbete/Independent project Kurskod/Code: EX0319 Omfattning på kursen/Extension of course: 30 hp Nivå och fördjupning på arbetet/Level and depth of project: Avancerad D/Advanced D Utgivningsort/Place of publishing: Grimsö/Uppsala Utgivningsår/Publication year: 2009 Program eller utbildning/Program: Fristående kurs Abstract: The main prey for lynx in northern Sweden is semi-domestic reindeer. Lynx often utilise their large prey for several days and therefore a special behaviour can be observed around a kill site. The aim of this study was to investigate behavioural characteristics of lynx around killed reindeer and examine factors that might affect the behaviour. -

Checklist of the Mallophaga of North America (North of Mexico), Which Reflects the Taxonomic Studies Published Since That Date

The Genera and Species of Mallopbaga of North America (North of Mexico) Part II. Suborder AMBLYCERA by K. C. Emerson, PhD. SKgT-SSTcTS'S-? SWW TO M"7-5001 PREFACE This volume is essentially a revision of my 1964 publication, Checklist of the Mallophaga of North America (north of Mexico), which reflects the taxonomic studies published since that date. Host criteria for the birds has been expanded to include consideration of all species listed in The A. 0. U. Checklist of North American Birds. Fifth Edition (1957). A few species of birds definitely known to be extinct are omitted from the listings of probable hosts, even though new species may still be found on museum skins. Mammal hosts considered remain those recorded in Millsr and Kellogg, List of North American Recent Mammals (1955), as; being found north of Mexico. Dr. Theresa Clay, British Museum (Natural History), ar.d especially Dr. Roger D. Price, University of Minnesota, during the last few years, have reviewed several genera of the Menoporidae; however, several of the larger genera are still in need of review. Unfortunately this volume could not be delayed until work on these genera is completed. CONTENTS BOOPIDAE Heterodoxus GYROPIDAE Gliricola Gyropus Macrogyropus Pitrufquenia LAEMOBOTHRIIDAE Laemobothrion MENOPONIDAE A ctornitbophi.lus Arnyrsidea Ancistrona Ardeiphilus Austromenopon Bonomiella Ciconiphilus Clayia Colpocephalum Comatomenopon Cuculiphilus Dennyus Eidmanniella Eucolpocephalum Eureum Fregatiella Gruimenopon Heleonomus Hohorstiella Holomenopon Kurodaia Longimenopon Machaerilaemus Menacanthus Menopon Myrsidea Nosopon Numidicola - Osborniella Piagetiella Plegadiphilus Procellariphaga Pseudomenopon Somaphantus Trinoton RICINIDAE Ricinus Trochiliphagus Trochiloectes TRIMENOPONIDAE Trimenopon Suborder AMBLYCERA Family BOOPIDAE Genus HETERODOXUS Heterodoxus LeSouef and Bullen. 1902. Vict. -

Infestation by Haematopinus Quadripertusus on Cattle in São

Research Note Rev. Bras. Parasitol. Vet., Jaboticabal, v. 21, n. 3, p. 315-318, jul.-set. 2012 ISSN 0103-846X (impresso) / ISSN 1984-2961 (eletrônico) Infestation by Haematopinus quadripertusus on cattle in São Domingos do Capim, state of Pará, Brazil Infestação por Haematopinus quadripertusus em bovinos de São Domingos do Capim, estado do Pará, Brasil Alessandra Scofield1*; Karinny Ferreira Campos2; Aryane Maximina Melo da Silva3; Cairo Henrique Sousa Oliveira4; José Diomedes Barbosa3; Gustavo Góes-Cavalcante1 1Laboratório de Parasitologia Animal, Programa de Pós-graduação em Saúde Animal na Amazônia, Faculdade de Medicina Veterinária, Universidade Federal do Pará – UFPA, Castanhal, PA, Brasil 2Programa de Pós-graduação em Ciência Animal, Universidade Federal do Pará – UFPA, Belém, PA, Brasil 3Programa de Pós-graduação em Saúde Animal na Amazônia, Universidade Federal do Pará – UFPA, Castanhal, PA, Brasil 4Programa de Pós-graduação em Ciência Animal, Escola de Veterinária, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais – UFMG, Belo Horizonte, MG, Brasil Received September 15, 2011 Accepted March 20, 2012 Abstract Severe infestation with lice was observed on crossbred cattle (Bos taurus indicus × Bos taurus taurus) in the municipality of São Domingos do Capim, state of Pará, Brazil. Sixty-five animals were inspected and the lice were manually collected, preserved in 70% alcohol and taken to the Animal Parasitology Laboratory, School of Veterinary Medicine, Federal University of Pará, Brazil, for identification. The adult lice were identified Haematopinusas quadripertusus, and all the cattle examined were infested by at least one development stage of this ectoparasite. The specimens collected were located only on the tail in 80% (52/65) of the cattle, while they were around the eyes as well as on the ears and tail in 20% (13/65). -

Species Almanac • Nature Activities At

The deeriNature Almanac What is the i in deeriNature? Is it information, internet? How about identification. When you go out on the Deer Isle preserves, what species are you almost certain to encounter? Which ones might you wish to identify? Then how do you organize your experience so that learning about the nearly overwhelming richness of nature becomes wonderfully satisfying? A century ago every farmer, medicine woman, and indeed any educated man or woman felt that they should have a solid knowledge of the plants around them. The Fairbanks Museum in St. Johnsbury, Vermont has maintained a Flower Table with labeled specimens since 1905. The Deer Isle-Stonington Historical Society has an antique herbarium collection made by Ada Southworth, a Dunham’s point rusticator. Today there are lovely field guides galore but the equivalent of a local list can come to you now by digital download. Here is an almanac, a list of likely plant and animal species (and something about rocks too) for our Deer Isle preserves, arranged according to season and habitat. Enjoy this free e-Book on your desktop, tablet or smartphone. Take this e-book with you on the trails and consult the Point of Interest signs. If you have a smartphone and adequate coverage, at some preserves a QR code will tell you more at the Points of Interest. After each category on the lists you will find suggestions for books to consult or acquire. You will have to read the on line reviews for apps as that field is developing too rapidly for any other approach. -

BÖCEKLERİN SINIFLANDIRILMASI (Takım Düzeyinde)

BÖCEKLERİN SINIFLANDIRILMASI (TAKIM DÜZEYİNDE) GÖKHAN AYDIN 2016 Editör : Gökhan AYDIN Dizgi : Ziya ÖNCÜ ISBN : 978-605-87432-3-6 Böceklerin Sınıflandırılması isimli eğitim amaçlı hazırlanan bilgisayar programı için lütfen aşağıda verilen linki tıklayarak programı ücretsiz olarak bilgisayarınıza yükleyin. http://atabeymyo.sdu.edu.tr/assets/uploads/sites/76/files/siniflama-05102016.exe Eğitim Amaçlı Bilgisayar Programı ISBN: 978-605-87432-2-9 İçindekiler İçindekiler i Önsöz vi 1. Protura - Coneheads 1 1.1 Özellikleri 1 1.2 Ekonomik Önemi 2 1.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 2 2. Collembola - Springtails 3 2.1 Özellikleri 3 2.2 Ekonomik Önemi 4 2.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 4 3. Thysanura - Silverfish 6 3.1 Özellikleri 6 3.2 Ekonomik Önemi 7 3.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 7 4. Microcoryphia - Bristletails 8 4.1 Özellikleri 8 4.2 Ekonomik Önemi 9 5. Diplura 10 5.1 Özellikleri 10 5.2 Ekonomik Önemi 10 5.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 11 6. Plocoptera – Stoneflies 12 6.1 Özellikleri 12 6.2 Ekonomik Önemi 12 6.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 13 7. Embioptera - webspinners 14 7.1 Özellikleri 15 7.2 Ekonomik Önemi 15 7.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 15 8. Orthoptera–Grasshoppers, Crickets 16 8.1 Özellikleri 16 8.2 Ekonomik Önemi 16 8.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 17 i 9. Phasmida - Walkingsticks 20 9.1 Özellikleri 20 9.2 Ekonomik Önemi 21 9.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 21 10. Dermaptera - Earwigs 23 10.1 Özellikleri 23 10.2 Ekonomik Önemi 24 10.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 24 11. Zoraptera 25 11.1 Özellikleri 25 11.2 Ekonomik Önemi 25 11.3 Bunları Biliyor musunuz? 26 12. -

Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections

SMITHSONIAN MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTIONS VOLUME 104, NUMBER 7 THE FEEDING APPARATUS OF BITING AND SUCKING INSECTS AFFECTING MAN AND ANIMALS BY R. E. SNODGRASS Bureau of Entomology and Plant Quarantine Agricultural Research Administration U. S. Department of Agriculture (Publication 3773) CITY OF WASHINGTON PUBLISHED BY THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION OCTOBER 24, 1944 SMITHSONIAN MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTIONS VOLUME 104, NUMBER 7 THE FEEDING APPARATUS OF BITING AND SUCKING INSECTS AFFECTING MAN AND ANIMALS BY R. E. SNODGRASS Bureau of Entomology and Plant Quarantine Agricultural Research Administration U. S. Department of Agriculture P£R\ (Publication 3773) CITY OF WASHINGTON PUBLISHED BY THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION OCTOBER 24, 1944 BALTIMORE, MO., U. S. A. THE FEEDING APPARATUS OF BITING AND SUCKING INSECTS AFFECTING MAN AND ANIMALS By R. E. SNODGRASS Bureau of Entomology and Plant Quarantine, Agricultural Research Administration, U. S. Department of Agriculture CONTENTS Page Introduction 2 I. The cockroach. Order Orthoptera 3 The head and the organs of ingestion 4 General structure of the head and mouth parts 4 The labrum 7 The mandibles 8 The maxillae 10 The labium 13 The hypopharynx 14 The preoral food cavity 17 The mechanism of ingestion 18 The alimentary canal 19 II. The biting lice and booklice. Orders Mallophaga and Corrodentia. 21 III. The elephant louse 30 IV. The sucking lice. Order Anoplura 31 V. The flies. Order Diptera 36 Mosquitoes. Family Culicidae 37 Sand flies. Family Psychodidae 50 Biting midges. Family Heleidae 54 Black flies. Family Simuliidae 56 Net-winged midges. Family Blepharoceratidae 61 Horse flies. Family Tabanidae 61 Snipe flies. Family Rhagionidae 64 Robber flies. Family Asilidae 66 Special features of the Cyclorrhapha 68 Eye gnats. -

Türleri Chewing Lice (Phthiraptera)

Kafkas Univ Vet Fak Derg RESEARCH ARTICLE 17 (5): 787-794, 2011 DOI:10.9775/kvfd.2011.4469 Chewing lice (Phthiraptera) Found on Wild Birds in Turkey Bilal DİK * Elif ERDOĞDU YAMAÇ ** Uğur USLU * * Selçuk University, Veterinary Faculty, Department of Parasitology, Alaeddin Keykubat Kampusü, TR-42075 Konya - TURKEY ** Anadolu University, Faculty of Science, Department of Biology, TR-26470 Eskişehir - TURKEY Makale Kodu (Article Code): KVFD-2011-4469 Summary This study was performed to detect chewing lice on some birds investigated in Eskişehir and Konya provinces in Central Anatolian Region of Turkey between 2008 and 2010 years. For this aim, 31 bird specimens belonging to 23 bird species which were injured or died were examined for the louse infestation. Firstly, the feathers of each bird were inspected macroscopically, all observed louse specimens were collected and then the examined birds were treated with a synthetic pyrethroid spray (Biyo avispray-Biyoteknik®). The collected lice were placed into the tubes with 70% alcohol and mounted on slides with Canada balsam after being cleared in KOH 10%. Then the collected chewing lice were identified under the light microscobe. Eleven out of totally 31 (35.48%) birds were found to be infested with at least one chewing louse species. Eighteen lice species were found belonging to 16 genera on infested birds. Thirteen of 18 lice species; Actornithophilus piceus piceus (Denny, 1842); Anaticola phoenicopteri (Coincide, 1859); Anatoecus pygaspis (Nitzsch, 1866); Colpocephalum heterosoma Piaget, 1880; C. polonum Eichler and Zlotorzycka, 1971; Fulicoffula lurida (Nitzsch, 1818); Incidifrons fulicia (Linnaeus, 1758); Meromenopon meropis Clay ve Meinertzhagen, 1941; Meropoecus meropis (Denny, 1842); Pseudomenopon pilosum (Scopoli, 1763); Rallicola fulicia (Denny, 1842); Saemundssonia lari Fabricius, O, 1780), and Trinoton femoratum Piaget, 1889 have been recorded from Turkey for the first time. -

Nestings of Some Passerine Birds in Western Alaska

64 Vol. 50 NESTINGS OF SOME PASSERINE BIRDS IN WESTERN ALASKA By LAWRENCE H. WALKINSHAW On May 25, 1946, John J. Stophlet, Jim Walkinshaw and.the writer reached Fair- banks, Alaska, bound for Bethel near the mouth of the Kuskokwim River, on the Bering Sea coast. Floods prevented landing at the air field at Bethel and our plane turned back to McGrath, 275 miles up-river. Bethel finally was reached by boat on June 1 and on June 4 w,e were flown to a cabin 30 miles to the west on the Johnson River. This river originates north and east of Bethel between the Yukon and Kuskokwim rivers and flows into the Kuskokwim about 30 miles below Bethel. Breeding birds were observed extensively, especially at the Johnson River locality, where we were stationed from June 4 to 22. Particularly favorable opportunities were presented to observe and photograph the nests of Yellow Wagtails, Redpolls and Tree Sparrows among the passerine birds of the area. Our notes on these speciesare presented ’ ’ herewith. Motacilla flava dascensis. Yellow Wagtail. On a short trip into the tundra northwest of Bethel, on June 2, we observed eight individuals, all males, and all singing. In 165 hours afield at Johnson River 153 individuals were counted. Each male was strongly territorial, defending its area against other male wagtails. Above the territory he gave his aerial song, but he also had song perches. If we appeared on a territory the male flew to meet us, coming to a spot about 8 to 15 meters overhead where he continued to scold while we were in close proximity of the nest area, This . -

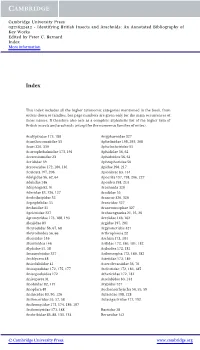

Identifying British Insects and Arachnids: an Annotated Bibliography of Key Works Edited by Peter C

Cambridge University Press 0521632412 - Identifying British Insects and Arachnids: An Annotated Bibliography of Key Works Edited by Peter C. Barnard Index More information Index This index includes all the higher taxonomic categories mentioned in the book, from orders down to families, but page numbers are given only for the main occurrences of those names. It therefore also acts as a complete alphabetic list of the higher taxa of British insects and arachnids (except for the numerous families of mites). Acalyptratae 173, 188 Anyphaenidae 327 Acanthosomatidae 55 Aphelinidae 198, 293, 308 Acari 320, 330 Aphelocheiridae 55 Acartophthalmidae 173, 191 Aphididae 56, 62 Acerentomidae 23 Aphidoidea 56, 61 Acrididae 39 Aphrophoridae 56 Acroceridae 172, 180, 181 Apidae 198, 217 Aculeata 197, 206 Apioninae 83, 134 Adelgidae 56, 62, 64 Apocrita 197, 198, 206, 227 Adelidae 146 Apoidea 198, 214 Adephaga 82, 91 Arachnida 320 Aderidae 83, 126, 127 Aradidae 55 Aeolothripidae 52 Araneae 320, 326 Aepophilidae 55 Araneidae 327 Aeshnidae 31 Araneomorphae 327 Agelenidae 327 Archaeognatha 21, 25, 26 Agromyzidae 173, 188, 193 Arctiidae 146, 162 Alexiidae 83 Argidae 197, 201 Aleyrodidae 56, 67, 68 Argyronetidae 327 Aleyrodoidea 56, 66 Arthropleona 22 Alucitidae 146 Aschiza 173, 184 Alucitoidea 146 Asilidae 172, 180, 181, 182 Alydidae 55, 58 Asiloidea 172, 181 Amaurobiidae 327 Asilomorpha 172, 180, 182 Amblycera 48 Asteiidae 173, 189 Anisolabiidae 41 Asterolecaniidae 56, 70 Anisopodidae 172, 175, 177 Atelestidae 172, 183, 185 Anisopodoidea 172 Athericidae 172, 181 Anisoptera 31 Attelabidae 83, 134 Anobiidae 82, 119 Atypidae 327 Anoplura 48 Auchenorrhyncha 54, 55, 59 Anthicidae 83, 90, 126 Aulacidae 198, 228 Anthocoridae 55, 57, 58 Aulacigastridae 173, 192 Anthomyiidae 173, 174, 186, 187 Anthomyzidae 173, 188 Baetidae 28 Anthribidae 83, 88, 133, 134 Beraeidae 142 © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521632412 - Identifying British Insects and Arachnids: An Annotated Bibliography of Key Works Edited by Peter C. -

Türleri Chewing Lice (Phthiraptera)

Kafkas Univ Vet Fak Derg ARTICLE IN PRESS RESEARCH ARTICLE xx (x): xxx-xxx, 2011 Chewing Lice (Phthiraptera) Species Found On Birds Along the Aras River, Iğdır, Eastern Turkey Bilal DIK * Çağan Hakkı ŞEKERCIOĞLU ** Mehmet Ali KIRPIK *** * University of Selçuk, College of Veterinary Medicine, Department of Parasitology, Alaaddin Keykubat Kampüsü, TR-42075 Konya - TURKEY ** Department of Biology, University of Utah, 257 South 1400 East, Salt Lake City, 84112 Utah - USA ** KuzeyDoga Society, İstasyon Mah., İsmail Aytemiz Cad., No. 161, TR--36200, Kars -TURKEY *** Kafkas University, Faculty of Science and Arts, Deparment of Biology, TR-36200 Kars -TURKEY Makale Kodu (Article Code): KVFD-2011-4075 Summary Chewing lice were sampled from the birds captured and ringed between September-October 2009 at the Aras River (Yukarı Çıyrıklı, Tuzluca, Iğdır) bird ringing station in eastern Turkey. Eighty-one bird specimens of 23 species were examined for lice infestation. All lice collected from the birds were placed in separate tubes with 70% alcohol. Louse specimens were cleared in 10% KOH, mounted in Canada balsam on glass slides and identified under a binocular light microscope. Sixteen out of 81 birds examined (19,75%) were infested with at least one chewing louse specimens. A total of 13 louse species were found on birds. These were: Austromenopon durisetosum (Blagoveshtchensky, 1948), Actornithophilus multisetosus (Blagoveshtchensky, 1940), Anaticola crassicornis (Scopoli, 1763), Cummingsiella ambigua (Burmeister, 1838), Menacanthus alaudae (Schrank, 1776), Menacanthus curuccae (Schrank, 1776), Menacanthus eurysternus (Burmeister, 1838), Menacanthus pusillus (Niztsch, 1866), Meromenopon meropis (Clay&Meinertzhagen, 1941), Myrsidea picae (Linnaeus, 1758), Pseudomenopon scopulacorne (Denny, 1842), Rhynonirmus scolopacis (Denny, 1842), and Trinoton querquedulae (Linnaeus, 1758). -

Co-Extinct and Critically Co-Endangered Species of Parasitic Lice, and Conservation-Induced Extinction: Should Lice Be Reintroduced to Their Hosts?

Short Communication Co-extinct and critically co-endangered species of parasitic lice, and conservation-induced extinction: should lice be reintroduced to their hosts? L AJOS R ÓZSA and Z OLTÁN V AS Abstract The co-extinction of parasitic taxa and their host These problems highlight the need to develop reliable species is considered a common phenomenon in the current taxonomical knowledge about threatened and extinct global extinction crisis. However, information about the parasites. Although the co-extinction of host-specific conservation status of parasitic taxa is scarce. We present a dependent taxa (mutualists and parasites) and their hosts global list of co-extinct and critically co-endangered is known to be a feature of the ongoing wave of global parasitic lice (Phthiraptera), based on published data on extinctions (Stork & Lyal, 1993; Koh et al., 2004; Dunn et al., their host-specificity and their hosts’ conservation status 2009), the magnitude of this threat is difficult to assess. according to the IUCN Red List. We list six co-extinct Published lists of threatened animal parasites only cover and 40 (possibly 41) critically co-endangered species. ixodid ticks (Durden & Keirans, 1996; Mihalca et al., 2011), Additionally, we recognize 2–4 species that went extinct oestrid flies (Colwell et al., 2009), helminths of Brazilian as a result of conservation efforts to save their hosts. vertebrates (Muñiz-Pereira et al., 2009) and New Zealand Conservationists should consider preserving host-specific mites and lice (Buckley et al., 2012). Our aim here is to lice as part of their efforts to save species. provide a critical overview of the conservation status of parasitic lice.