Catalogue and Book Reviews, Pp. 48-53

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Legacy Regained: Niko and the Russian Avant-Garde

A LEGACY REGAINED: NIKO AND THE RUSSIAN AVANT-GARDE PALACE EDITIONS Contents 8 Foreword Evgeniia Petrova 9 Preface Job de Ruiter 10 Acknowledgements and Notes to the Reader John E. Bowlt and Mark Konecny 13 Introduction John E. Bowlt and Mark Konecny Part I. Nikolai Khardzhiev and the Russian Avant Garde Remembering Nikolai Khardzhiev 21 Nikolai Khardzhiev RudolfDuganov 24 The Future is Now! lra Vrubel-Golubkina 36 Nikolai Khardzhiev and the Suprematists Nina Suetina 43 Nikolai Khardzhiev and the Maiakovsky Museum, Moscow Gennadii Aigi 50 My Memoir of Nikolai Khardzhiev Vyacheslav Ivanov 53 Nikolai Khardzhiev and My Family Zoya Ender-Masetti 57 My Meetings with Nikolai Khardzhiev Galina Demosfenova 59 Nikolai Khardzhiev, Knight of the Avant-garde Jean-C1aude Marcade 63 A Sole Encounter Szymon Bojko 65 The Guardian of the Temple Andrei Nakov 69 A Prophet in the Wilderness John E. Bowlt 71 The Great Commentator, or Notes About the Mole of History Vasilii Rakitin Writings by Nikolai Khardzhiev Essays 75 Autobiography 76 Poetry and Painting:The Early Maiakovsky 81 Cubo-Futurism 83 Maiakovsky as Partisan 92 Painting and Poetry Profiles ofArtists and Writers 99 Elena Guro 101 Boris Ender 103 In Memory of Natalia Goncharova and Mikhail Larionov 109 Vladimir Maiakovsky 122 Velimir Khlebnikov 131 Alexei Kruchenykh 135 VladimirTatlin 137 Alexander Rodchenko 139 EI Lissitzky Contents Texts Edited and Annotated by Nikolai Khardzhiev 147 Nikolai Khardzhiev Introductions to Kazimir Malevich's Autobiography (Parts 1 and 2) 157 Kazimir Malevieh Autobiography 172 Nikolai Khardzhiev Introduction to Mikhail Matiushin's The Russian Cubo-Futurists 173 Mikhail Matiushin The Russian Cubo-Futurists 183 Alexei Morgunov A Memoir 186 Nikolai Khardzhiev Introduction to Khlebnikov Is Everywhere! 187 Khlebnikov is Everywhere! Memoirs by Oavid Burliuk, Nadezhda Udaltsova, Amfian Reshetov, and on Osip Mandelshtam 190 Nikolai Khardzhiev Introduction to Lev Zhegin's Remembering Vasilii Chekrygin 192 Lev Zhegin Remembering Vasilii Chekrygin Part 11. -

Henryk Berlewi

HENRYK BERLEWI HENRYK © 2019 Merrill C. Berman Collection © 2019 AGES IM CO U N R T IO E T S Y C E O L L F T HENRYK © O H C E M N 2019 A E R M R R I E L L B . C BERLEWI (1894-1967) HENRYK BERLEWI (1894-1967) Henryk Berlewi, Self-portrait,1922. Gouache on paper. Henryk Berlewi, Self-portrait, 1946. Pencil on paper. Muzeum Narodowe, Warsaw Published by the Merrill C. Berman Collection Concept and essay by Alla Rosenfeld, Ph.D. Design and production by Jolie Simpson Edited by Dr. Karen Kettering, Independent Scholar, Seattle, USA Copy edited by Lisa Berman Photography by Joelle Jensen and Jolie Simpson Printed and bound by www.blurb.com Plates © 2019 the Merrill C. Berman Collection Images courtesy of the Merrill C. Berman Collection unless otherwise noted. © 2019 The Merrill C. Berman Collection, Rye, New York Cover image: Élément de la Mécano- Facture, 1923. Gouache on paper, 21 1/2 x 17 3/4” (55 x 45 cm) Acknowledgements: We are grateful to the staf of the Frick Collection Library and of the New York Public Library (Art and Architecture Division) for assisting with research for this publication. We would like to thank Sabina Potaczek-Jasionowicz and Julia Gutsch for assisting in editing the titles in Polish, French, and German languages, as well as Gershom Tzipris for transliteration of titles in Yiddish. We would also like to acknowledge Dr. Marek Bartelik, author of Early Polish Modern Art (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2005) and Adrian Sudhalter, Research Curator of the Merrill C. -

"The Architecture of the Book": El Lissitzky's Works on Paper, 1919-1937

"The Architecture of the Book": El Lissitzky's Works on Paper, 1919-1937 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Johnson, Samuel. 2015. "The Architecture of the Book": El Lissitzky's Works on Paper, 1919-1937. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:17463124 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA “The Architecture of the Book”: El Lissitzky’s Works on Paper, 1919-1937 A dissertation presented by Samuel Johnson to The Department of History of Art and Architecture in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History of Art and Architecture Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2015 © 2015 Samuel Johnson All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Maria Gough Samuel Johnson “The Architecture of the Book”: El Lissitzky’s Works on Paper, 1919-1937 Abstract Although widely respected as an abstract painter, the Russian Jewish artist and architect El Lissitzky produced more works on paper than in any other medium during his twenty year career. Both a highly competent lithographer and a pioneer in the application of modernist principles to letterpress typography, Lissitzky advocated for works of art issued in “thousands of identical originals” even before the avant-garde embraced photography and film. -

Russian Museums Visit More Than 80 Million Visitors, 1/3 of Who Are Visitors Under 18

Moscow 4 There are more than 3000 museums (and about 72 000 museum workers) in Russian Moscow region 92 Federation, not including school and company museums. Every year Russian museums visit more than 80 million visitors, 1/3 of who are visitors under 18 There are about 650 individual and institutional members in ICOM Russia. During two last St. Petersburg 117 years ICOM Russia membership was rapidly increasing more than 20% (or about 100 new members) a year Northwestern region 160 You will find the information aboutICOM Russia members in this book. All members (individual and institutional) are divided in two big groups – Museums which are institutional members of ICOM or are represented by individual members and Organizations. All the museums in this book are distributed by regional principle. Organizations are structured in profile groups Central region 192 Volga river region 224 Many thanks to all the museums who offered their help and assistance in the making of this collection South of Russia 258 Special thanks to Urals 270 Museum creation and consulting Culture heritage security in Russia with 3M(tm)Novec(tm)1230 Siberia and Far East 284 © ICOM Russia, 2012 Organizations 322 © K. Novokhatko, A. Gnedovsky, N. Kazantseva, O. Guzewska – compiling, translation, editing, 2012 [email protected] www.icom.org.ru © Leo Tolstoy museum-estate “Yasnaya Polyana”, design, 2012 Moscow MOSCOW A. N. SCRiAbiN MEMORiAl Capital of Russia. Major political, economic, cultural, scientific, religious, financial, educational, and transportation center of Russia and the continent MUSEUM Highlights: First reference to Moscow dates from 1147 when Moscow was already a pretty big town. -

Pushkin and the Futurists

1 A Stowaway on the Steamship of Modernity: Pushkin and the Futurists James Rann UCL Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2 Declaration I, James Rann, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 3 Acknowledgements I owe a great debt of gratitude to my supervisor, Robin Aizlewood, who has been an inspirational discussion partner and an assiduous reader. Any errors in interpretation, argumentation or presentation are, however, my own. Many thanks must also go to numerous people who have read parts of this thesis, in various incarnations, and offered generous and insightful commentary. They include: Julian Graffy, Pamela Davidson, Seth Graham, Andreas Schönle, Alexandra Smith and Mark D. Steinberg. I am grateful to Chris Tapp for his willingness to lead me through certain aspects of Biblical exegesis, and to Robert Chandler and Robin Milner-Gulland for sharing their insights into Khlebnikov’s ‘Odinokii litsedei’ with me. I would also like to thank Julia, for her inspiration, kindness and support, and my parents, for everything. 4 Note on Conventions I have used the Library of Congress system of transliteration throughout, with the exception of the names of tsars and the cities Moscow and St Petersburg. References have been cited in accordance with the latest guidelines of the Modern Humanities Research Association. In the relevant chapters specific works have been referenced within the body of the text. They are as follows: Chapter One—Vladimir Markov, ed., Manifesty i programmy russkikh futuristov; Chapter Two—Velimir Khlebnikov, Sobranie sochinenii v shesti tomakh, ed. -

Articles John E. Bowlt David Burliuk, the Fa- Ther Of

ARTICLES JOHN E. BOWLT DAVID BURLIUK, THE FA- THER OF RUSSIAN FUTURISM The poet Boris Lavrenev has left the following description of his friend and mentor, David Davidovich Burliuk: "The thickset, clumsy, and shortleg- ged David Burliuk, putting his inseparable lorgnette to his eye, stood before his superb, rather Impressionist landscapes hung all over the walls of his stu- dio, and ... smirking, said that you won't get much glory or capital today by following classical traditions and serious painting, and that you have to stup- efy the bourgeoisie and the philistine with the cudgel of novelty." During the heyday of Russian Cubo-Futurism (ca. 1912-ca. 1916); Burliuk certainly wielded the cudgel of novelty and many were bruised by it. Perhaps that is one reason why people have tended to avoid direct confrontation with Bur- liuk and why, even today, he is known more as a barrack-room lawyer, a "hooligan of the palette,"2 rather than as an original painter and poet and an astute critic. No history of twentieth-century Russian culture can be written without substantial reference to the life and work of David Burliuk, and there is no question that the Russian avant-garde-the experimental movements in art and literature of the 1910s and 1920s-would have developed quite as dra- matically if Burliuk had not undertaken his many creative and organiza- tional activities. As his fellow Futurist, Vasilii Kamenskii, once said: "The name of David Burliuk was, and always is, an international name, like the sun in the heavens."3 Put more succinctly, he was, as Vasilii Kandinsky called 1. -

Downloaded from the Web-Site

THE INSTITUTE OF MODERN RUSSIAN CULTURE AT BLUE LAGOON NEWSLETTER No. 49, February, 2005 IMRC, Mail Code 4353, USC, Los Angeles, Ca. 90089-4353, USA Tel.: (213) 740-2735 or (213) 740-6120; Fax: (213) 740-8550; E: [email protected] website: http://www.usc.edu./dept/LAS/IMRC STATUS This is the forty-ninth biannual Newsletter of the IMRC and follows the last issue that appeared in August, 2004. The information presented here relates primarily to events connected with the IMRC during the fall and winter of 2004. For the benefit of new readers, data on the present structure of the IMRC are given on the last page of this issue. IMRC Newsletters for 1979-2001 are available electronically and can be requested via e-mail at [email protected]. A full run can also be supplied on a CD disc (containing a searchable version in Microsoft Word) at a cost of $25.00, shipping included (add $5.00 if overseas airmail. Beginning in August, 2004, the IMRC has transferred the Newsletter to an electronic format and, henceforth, individuals and institutions on our courtesy list are receiving the issues as an e-attachment. Members in full standing, however, continue to receive hard copies of the Newsletter as well as the text in electronic format, wherever feasible. Please send us new and corrected e-mail addresses. An illustrated brochure describing the programs, collections, and functions of the IMRC is also available RUSSIANGLIISKII These days travellers to Moscow are struck by the increasing number of English – or, rather, American – calques entering the Russian language. -

Russian Plates Pp. 290-303

INDEX OF ARTISTS Dorfman, Elizaveta, 733 Ivanova, Vera, 868, 869 Litvak, M., 652 Index Dovgal’, Oleksandr, 783 Izenberg, Vladimir, 592–594, 643 Liubavina, Nadezhda, 74, 186, 364 Adlivankin, Samuil, 524, 525, 572, 573 Dubyns’kii, Hr., 858 (see also Author Index) Izoram, 1019 Liubimov, Aleksandr, 1197 Coordinated by Sarah Suzuki. (see also Author Index) Duplitskii, 1019 Liushin, 896 Contributors include Sienna Brown, Aivazovskii, 1021 Dvorakovskii, Valerian, 1080 K., B., 697, 698 Lopukhin, Aleksandr, 128 (see also Author Emily Capper, and Jennifer Roberts. Akishin, Leonid, 1019 K., F. P., 1151 Index) Aksel’rod, Meer (Mark), 789 Echeistov, Georgii, 284, 378–382, 455 K., N., 222 Lozowick, Louis, 706 Aleksandrova, Vera, 329 Efimov, B., 532 Kalashnikov, Mikhail, 263, 264 All numbers refer to the Checklist. Alekseev, Nikolai, 526, 574 Egorov, Vladimir, 583 Kalmykov, Mykola, 262 M., D., 608 Al’tman, Natan, 55, 56, 59, 117, 143, Elin, V. M., 1205 Kamenskii, Vasilii, 75, 76, 90, 94, 95, M., E., 751 144, 169, 215, 330, 331, 364, 447, Elkin, Vasilii, 793 142, 150, 164–66, 218 (see also Author Makarov, Mikhail, 1023 451, 527, 575, 636, 731, 1019, 1124, El’kina, D., 326 (see also Author Index) Index) Makletsov, Sergei, 206, 207 1162 (see also Author Index) Ender, Boris, 533, 584, 1228 Kandinsky, Vasily, 181, 223 (see also Malevich, Kazimir, 21, 37–40, 55, 56, Andreev, Aleksandr, 4 Epifanov, Gennadii, 1081 Author Index) 68, 69, 79–81, 91, 129, 236, Andreevskaia, M., 361 Epple, L., 1056 Kanevskii, A., 852 306–308, 348, 884, 1126–1128, 1153 Andronova, -

De Khardzhiev-Collectiestedelijk Museum Amsterdamrussische Avant-Garde

De Khardzhiev- collectie Stedelijk Museumavant-garde AmsterdamRussische Geurt Imanse nai010 uitgevers Frank van Lamoen Mikhail Fedorovich Larionov 1881 Tiraspol – 1964 Parijs Hoewel Khardzhiev in zijn collectie van Kazimir Malevich de kunst, 1899–1904). Zijn schilderkunst op dat moment is een Ondertussen was zijn werk, veelal samen met dat van 1 In de woorden van George Costakis, zoals geciteerd door, meeste werken had, was deze voor hem toch niet de belang- mengvorm van de stijl van de Mir iskusstva-schilders (genre- Goncharova, in 1912 en 1913 te zien op tentoonstellingen Gennadi Aigi, Khardzhievs oud- rijkste kunstenaar. Dat was Mikhail Larionov. ‘We weten taferelen) en een voor Rusland innovatief impressionisme in München, Berlijn en Londen. collega in het Mayakovsky Museum. Zie Aigi 2002, p. 46. 202 natuurlijk dat Malevich heel veel betekent voor Khardzhiev, (stadslandschappen en natuurstudies).5 Met Diaghilev en 203 Toch was het juist vanwege de elementen van Russische 2 Vrubel-Golubkina 2002, p. 30. maar we weten ook dat hij Larionov gewoon adoreert. Hij is zo de Mir iskusstva-schilders Leon Bakst (1866–1924) en Pavel volkskunst in het neoprimitivistische werk van Larionov en 3 Aigi 2002, p. 46. dol op hem dat het lijkt alsof hij met hem naar bed zou willen.’1 Kuznetsov (1878–1968) bezocht hij in 1906 Parijs voor de door Goncharova dat Diaghilev hen in 1914 uitnodigde de decors en 4 Rakitin 2002, p. 72. Dat Larionov qua aantal werken in Khardzhievs collectie een Diaghilev georganiseerde grote Russische inzending voor de kostuums voor uitvoeringen van de ballet-opera Le Coq d’Or 5 Marcadé 2004, p. -

Checklist of the Judith Rothschild Foundation Gift

Checklist of The Judith This checklist is a comprehensive ascertained through research. When a For books and journals, dimensions Inscriptions that are of particular his- record of The Judith Rothschild place of publication or the publisher given are for the largest page and, in torical or literary interest on individual Rothschild Foundation Gift Foundation gift to The Museum of was neither printed in the book nor cases where the page sizes vary by books are noted. Modern Art in 2001. The cataloguing identified through research, the des- more than 1/4,” they are designated Coordinated by Harper Montgomery system reflects museum practice in ignation “n.s” (not stated) is used. irregular (“irreg.”). For the Related The Credit line, Gift of The Judith under the direction of Deborah Wye. general and the priorities of The Similarly, an edition size is some- Material, single-sheet dimensions in Rothschild Foundation, pertains to all Museum of Modern Art’s Department times given as “unknown” if the print which the height or width varies from items on this checklist. To save space Researched and compiled by of Prints and Illustrated Books in par- run could not be verified. City names one end to the other by more than and avoid redundancy, this line does Jared Ash, Sienna Brown, Starr ticular. Unlike most bibliographies are given as they appear printed in 1/4” are similarly designated irregular. not appear in the individual entries. Figura, Raimond Livasgani, Harper and library catalogues, it focuses on each book; in different books the An additional credit may appear in Montgomery, Jennifer Roberts, artists rather than authors, and pays same city may be listed, for example, Medium descriptions (focusing on parentheses near the end of certain Carol Smith, Sarah Suzuki, and special attention to mediums that as Petersburg, St. -

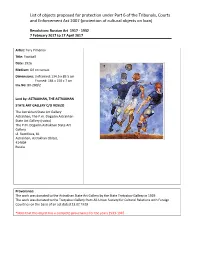

List of Objects Proposed for Protection Under Part 6 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (Protection of Cultural Objects on Loan)

List of objects proposed for protection under Part 6 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (protection of cultural objects on loan) Revolution: Russian Art 1917 - 1932 7 February 2017 to 17 April 2017 Artist: Yury Pimenov Title: Football Date: 1926 Medium: Oil on canvas Dimensions: Unframed: 134.5 x 89.5 cm Framed: 184 x 150 x 7 cm Inv.No: BX-280/2 Lent by: ASTRAKHAN, THE ASTRAKHAN STATE ART GALLERY C/O ROSIZO The Astrakhan State Art Gallery Astrakhan, The P.m. Dogadin Astrakhan State Art Gallery (rosizo) The P.M. Dogadin Astrakhan State Art Gallery ul. Sverdlova, 81 Astrakhan, Astrakhan Oblast, 414004 Russia Provenance: The work was donated to the Astrakhan State Art Gallery by the State Tretyakov Gallery in 1929. The work was donated to the Tretyakov Gallery from All-Union Society for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries on the basis of an act dated 23.02.1929 *Note that this object has a complete provenance for the years 1933-1945 List of objects proposed for protection under Part 6 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (protection of cultural objects on loan) Revolution: Russian Art 1917 - 1932 7 February 2017 to 17 April 2017 Artist: Ekaterina Zernova Title: Tomato Paste Factory Date: 1929 Medium: Oil on canvas Dimensions: Unframed: 141 x 110 cm Framed: 150 x 120 x 7 cm Inv.No: BX-280/1 Lent by: ASTRAKHAN, THE ASTRAKHAN STATE ART GALLERY C/O ROSIZO The Astrakhan State Art Gallery Astrakhan, The P.m. Dogadin Astrakhan State Art Gallery (rosizo) The P.M. -

Shapiro Auctions

Shapiro Auctions RUSSIAN AND INTERNATIONAL ART AND ANTIQUES Saturday - May 18, 2013 RUSSIAN AND INTERNATIONAL ART AND ANTIQUES 1: RUSSIAN ICON OF SPAS OPLECHNII 18TH CENTURY USD 1,800 - 2,200 A RUSSIAN ICON OF SPAS OPLECHNII, 18th C., Egg tempera and gesso on wood panel with a kovcheg. Two insert splints on the back. 31.5 x 26.2 cm. (12 3/8 x 10 1/4 in.) PROVENANCE: Purchased by the Mother of the current owner in Russia during the 1920s; thence by descent in Family Collection. LOT NOTES: During the late 1920s, shortly after the Russian Revolution, two young New York society women, sisters Adelaide and Helen Hooker secretly traveled to Russia “out of curiosity and cussedness.” Unbeknownst to their father, the president of the American Defense Society, they spent over six months in snowy Russia, pursuing adventure in Moscow, Leningrad, Vladimir, Novgorod, and Suzdal among other cities. Searching for a glimpse of “Old Russia,” the women sought-out ancient churches and monasteries, just as they were being taken over by the government and converted to Anti-Religious museums. This icon was among those that Adelaide and Helen Hooker purchased from these establishments and brought to the United States, in effect saving them from becoming victims of iconoclasm. In the States, the icons were kept in esteemed family collections. One of the sisters would go on to marry the IRA officer Ernie O'Malley, the other the writer John P. Marquand. Their youngest sister, Blanchette, went on to marry John D. Rockefeller III, and would become a major benefactor of the Museum of Modern Art, where she served as president from 1972 to 1985.