Chamber-Music in Melbourne 1877–1901:A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Auckland at 7.00Pm

Wagner Society of New Zealand Patron: Sir Donald McIntyre NEWSLETTER Vol. 13 No. 4 April 2017 President’s Report for 2016 AGM - 21 May 2017 Formal Notice The Wagner Society of New Zealand AGM is to be held on Sunday 21 May 2017 in St Heliers Community Centre, 100 St Heliers Bay Road, Auckland at 7.00pm. So far, Committee and Office-Bearer nominations have been received as follows: President ................. Chris Brodrick Vice President ............ Ken Tomkins Secretary ....................... Peter Rowe Treasurer ................. Jeanette Miller PR/Liaison ..................Gloria Streat Bob O’Hara Committee . John Davidson, Lesley Kendall, Juliet Rowe Bob O’Hara as Uberto (La Serva Padrona.) Michael Sinclair If you wish to make a nomination: In this, the 22nd President’s report to opera trips including both Adelaide Phone: Peter at 09-520 4690 or the Wagner Society of New Zealand, I Rings, the 2013 Melbourne Ring and he Email: [email protected]. would like, among all the thank yous, to has plans to attend the San Francisco to be sent a form. Nominations can focus some attention on two members. Ring next year. also be made from the floor at the One has been with us from 1995 and Bob and other WSNZ members’ ability meeting. after many years of service has recently to attend these overseas productions stepped down from the committee. The is enabled by the wonderful work of Membership renewals other, who may not have been with us Michael Sinclair, as the organising force Included with this newsletter is a from the start, has nonetheless made a behind our overseas trips. -

The Year's Music

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com fti E Y LAKS MV5IC 1896 juu> S-q. SV- THE YEAR'S MUSIC. PIANOS FOR HIRE Cramer FOR HARVARD COLLEGE LIBRARY Pianos BY All THE BEQUEST OF EVERT JANSEN WENDELL (CLASS OF 1882) OF NEW YORK Makers. 1918 THIS^BQQKJS FOR USE 1 WITHIN THE LIBRARY ONLY 207 & 209, REGENT STREET, REST, E.C. A D VERTISEMENTS. A NOVEL PROGRAMME for a BALLAD CONCERT, OR A Complete Oratorio, Opera Recital, Opera and Operetta in Costume, and Ballad Concert Party. MADAME FANNY MOODY AND MR. CHARLES MANNERS, Prima Donna Soprano and Principal Bass of Royal Italian Opera, Covent Garden, London ; also of 5UI the principal ©ratorio, dJrtlustra, artii Sgmphoiu) Cxmctria of ©wat Jfvitain, Jtmmca anb Canaba, With their Full Party, comprising altogether Five Vocalists and Three Instrumentalists, Are now Booking Engagements for the Coming Season. Suggested Programme for Ballad and Opera (in Costume) Concert. Part I. could consist of Ballads, Scenas, Duets, Violin Solos, &c. Lasting for about an hour and a quarter. Part II. Opera or Operetta in Costume. To play an hour or an hour and a half. Suggested Programme for a Choral Society. Part I. A Small Oratorio work with Chorus. Part II. An Operetta in Costume; or the whole party can be engaged for a whole work (Oratorio or Opera), or Opera in Costume, or Recital. REPERTOIRE. Faust (Gounod), Philemon and Baucis {Gounod) (by arrangement with Sir Augustus Harris), Maritana (Wallace), Bohemian Girl (Balfe), and most of the usual Oratorios, &c. -

'Wagner on a Shoestring' by Suzanne Chaundy, 25 March 2018

'Wagner on a Shoestring' by Suzanne Chaundy, 25 March 2018 12.30pm: DVD: 'Das Liebesverbot', Act 2 2.00pm: Presentation by Suzanne Chaundy DVD: Das Liebesverbot Act 2 Wagner's rarely performed early comic opera (1836), based on Shakespeare's Measure for Measure, enjoys its Spanish debut in a new production by director Kaspar Holten. The lively score boasts clear Italian, French and Weberian influences that predate the composer's mature voice, yet the music continually delights with the unmistakable emergence of Wagner's precocious genius. His adaptation of the Bard's play reflects the rebellious mood of a revolutionary Germany, vindicating sensual love and attacking the fanatical repression of sexuality by a puritanical and hypocritical authority. Ivor Bolton conducts a vibrant cast with the chorus and orchestra from the Theatro Real, Madrid (2016). 'Wagner on a Shoestring' by Suzanne Chaundy Suzanne Chaundy is a highly regarded director of opera, drama, outdoor spectacle and special events, and will speak about her Wagner productions for Melbourne Opera. Miki Oikowa and Suzanne Chaundy She began directing as an undergraduate at the University of Melbourne and was subsequently fast-tracked into the NIDA Directing Course. Best known as an opera director, she began on this path as a trainee director with the Victorian State Opera. Her 2012 production of Cosi Fan Tutte for Melbourne Opera at Melbourne’s Athenaeum Theatre (nominated for Best Director – Green Room Awards) resulted in her becoming something of a regular for the company directing new productions of Der Freischütz and Maria Stuarda in 2015,The Abduction from the Seraglio, Tannhäuser and Anna Bolena in 2016, Lohengrin in 2017 and Tristan und Isolde in 2018. -

PLATTEGROND VAN HET CONCERTGEBOUW Begane Grond 1E

PLATTEGROND VAN HET CONCERTGEBOUW JULI AUGUSTUS Begane grond Entree Café Woensdag 2 augustus 2017 Trap Trap T Grote Zaal 20.00 uur Zuid Würth Philharmoniker Achterzaal Garderobe Dennis Russell Davies, dirigent Voorzaal Podium Robeco Ray Chen, viool Grote Zaal Summer Restaurant Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart 1756-1791 Symfonie nr. 32 in G, KV 318 (1779) Noord Allegro spiritoso Andante Trap Trap Primo tempo Felix Mendelssohn 1809-1847 Vioolconcert in e, op. 64 (1844) Allegro molto appassionato 1e verdieping Andante Pleinfoyer Allegretto non troppo - Allegro molto vivace Museum- SummerNights Live! foyer PAUZE T Trap Trap Antonín Dvořák 1841-1904 Solistenfoyer Negende symfonie in e, op. 95 ‘Uit de Balkon Zuid Nieuwe Wereld’ (1893) Podium Adagio - Allegro molto Frontbalkon Largo Scherzo: Molto vivace Kleine Zaal Grote Zaal Allegro con fuoco Muziek beleven doet u samen. Veel van Podium Balkon Noord onze bezoekers willen optimaal van de muziek genieten door geconcentreerd en in stilte te Dirigenten- luisteren. Wij vragen u daar rekening mee te Trap foyer Trap houden. WWW.ROBECOSUMMERNIGHTS.NL Informatiebeveiliging in de ambulancezorg Toelichting/TOELICHTING/Biografie//Summary//Concerttip BIOGRAFIE SUMMARYjuli-aug 2015 EN VERDER... In januari 1779 keerde Wolfgang Amadeus het nieuwe vioolconcert was onder meer dat De Würth Philharmoniker draagt de naam When Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart worked as Social media Robeco Mozart van zijn reis naar Parijs terug in de solist meteen met de deur in huis komt van zijn initiatiefnemer: de Duitse onderne- the court organist for Count Archbishop Salzburg, waar zijn (ongelukkige) dienstver- vallen, dat de solocadens niet aan het eind mer en mecenas Reinhold Würth. Het gloed- Colloredo in Salzburg, he was expected to Meer Robeco SummerNights online! De Robeco SummerNights komen voort uit band bij prins-aartsbisschop Colloredo werd van het eerste deel zit maar veel eerder, en nieuwe orkest, met het juist gebouwde provide new compositions for the court and Volg Het Concertgebouw op social media en een unieke samenwerking tussen Robeco en voortgezet. -

2008 ANZARME Conference Proceedings

Australian and New Zealand Association for Research in Music Education Proceedings of the XXXth Annual Conference Innovation and Tradition: Music Education Research 3 – 5 October 2008 Melbourne, Victoria, Australia 1 All published papers have been subjected to a blind peer-review process before being accepted for inclusion in the Conference Proceedings Publisher Australian and New Zealand Association for Research in Music Education (ANZARME, Melbourne, Australia Editor Dr Jane Southcott Review Panel Prof. Pam Burnard Prof. Gordon Cox Dr Jean Callaghan Dr James Cuskelly Associate Prof. Peter Dunbar-Hall Dr Helen Farrell Dr Jill Ferris Professor Mark Fonder Dr Scott Harrison Dr Bernard Holkner Dr Neryl Jeanneret Dr Anne Lierse Dr Sharon Lierse Dr Janet McDowell Dr Bradley Merrick Dr Stephanie Pitts Dr Joan Pope Assoc. Prof. Robin Stevens Dr Peter de Vries Assoc. Prof. Robert Walker Printed by Monash University Format CD ROM ISBN: 978-0-9803116-5-5 2 CONTENTS Keynote Address: The First Musical Festival of the Empire 1911: 1 Tradition as innovative propaganda Thérèse Radic, University of Melbourne The artist as academic: Arts practice as research/as a site of 15 knowledge Diana Blom, University of Western Sydney Dawn Bennett, Curtin University David Wright, University of Western Sydney Aural traditions and their implications for music education 26 Roger Buckton, University of Canterbury, New Zealand A retrospection of the 1960s music education reforms in the USA 36 Harry Burke, Monash University Through the Eyes of Victor McMahon: The Flute -

Discovering the Contemporary Relevance of the Victorian Flute Guild

Discovering the Contemporary Relevance of the Victorian Flute Guild Alice Bennett © 2012 Statement of Responsibility: This document does not contain any material, which has been accepted for the award of any other degree from any university. To the best of my knowledge, this document does not contain any material previously published or written by any other person, except where due reference is given. Candidate: Alice Bennett Supervisor: Dr. Joel Crotty Signed:____________________ Date:____________________ 2 Contents Statement of Responsibility: ................................................................................................................... 2 Chapter One ............................................................................................................................................ 5 Introduction ........................................................................................................................................ 5 Methodology ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Literature Review ................................................................................................................................ 9 Chapter Outlines ............................................................................................................................... 11 Chapter Two ......................................................................................................................................... -

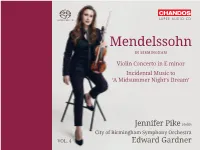

Mendelssohn in BIRMINGHAM

SUPER AUDIO CD Mendelssohn IN BIRMINGHAM Violin Concerto in E minor Incidental Music to ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’ Jennifer Pike violin City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra VOL. 4 Edward Gardner Painting by Thomas Hildebrandt (1804 – 1874) / Stadtgeschichtliches Museum, Leipzig / AKG Images, London Felix Mendelssohn, 1845 Mendelssohn, Felix Felix Mendelssohn (1809 – 1847) Mendelssohn in Birmingham, Volume 4 Concerto, Op. 64* 27:56 in E minor • in e-Moll • en mi mineur for Violin and Orchestra 1 Allegro molto appassionato – Cadenza ad libitum – Tempo I – Più presto – Sempre più presto – Presto – 12:55 2 Andante – Allegretto non troppo – 9:01 3 Allegro molto vivace 6:00 Incidental Music to ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’, Op. 61† 39:44 (Ein Sommernachtstraum) by William Shakespeare (1564 – 1616) 4 Overture (Op. 21). Allegro di molto – [ ] – Tempo I – Poco ritenuto 11:25 5 1 Scherzo (After the end of the first act). Allegro vivace 4:30 6 3 Song with Chorus. Allegro ma non troppo 3:57 7 5 Intermezzo (After the end of the second act). Allegro appassionato – Allegro molto comodo 3:21 3 8 7 Notturno (After the end of the third act). Con moto tranquillo 5:34 9 9 Wedding March (After the end of the fourth act). Allegro vivace 4:30 10 11 A Dance of Clowns. Allegro di molto 1:33 11 Finale. Allegro di molto – Un poco ritardando – A tempo I. Allegro molto 4:28 TT 67:57 Rhian Lois soprano I† Keri Fuge soprano II† Jennifer Pike violin* CBSO Youth Chorus† Julian Wilkins chorus master City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra Zoë Beyers leader Edward Gardner 4 Mendelssohn: Violin Concerto in E minor / A Midsummer Night’s Dream Introduction fine violinist himself. -

Maud Powell As an Advocate for Violinists, Women, and American Music Catherine C

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2012 "The Solution Lies with the American Women": Maud Powell as an Advocate for Violinists, Women, and American Music Catherine C. Williams Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC “THE SOLUTION LIES WITH THE AMERICAN WOMEN”: MAUD POWELL AS AN ADVOCATE FOR VIOLINISTS, WOMEN, AND AMERICAN MUSIC By CATHERINE C. WILLIAMS A Thesis submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Music Degree Awarded: Summer Semester, 2012 Catherine C. Williams defended this thesis on May 9th, 2012. The members of the supervisory committee were: Denise Von Glahn Professor Directing Thesis Michael Broyles Committee Member Douglass Seaton Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the thesis has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For Maud iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my parents and my brother, Mary Ann, Geoff, and Grant, for their unceasing support and endless love. My entire family deserves recognition, for giving encouragement, assistance, and comic relief when I needed it most. I am in great debt to Tristan, who provided comfort, strength, physics references, and a bottomless coffee mug. I would be remiss to exclude my colleagues in the musicology program here at The Florida State University. The environment we have created is incomparable. To Matt DelCiampo, Lindsey Macchiarella, and Heather Paudler: thank you for your reassurance, understanding, and great friendship. -

Song & Music in the Movement

Transcript: Song & Music in the Movement A Conversation with Candie Carawan, Charles Cobb, Bettie Mae Fikes, Worth Long, Charles Neblett, and Hollis Watkins, September 19 – 20, 2017. Tuesday, September 19, 2017 Song_2017.09.19_01TASCAM Charlie Cobb: [00:41] So the recorders are on and the levels are okay. Okay. This is a fairly simple process here and informal. What I want to get, as you all know, is conversation about music and the Movement. And what I'm going to do—I'm not giving elaborate introductions. I'm going to go around the table and name who's here for the record, for the recorded record. Beyond that, I will depend on each one of you in your first, in this first round of comments to introduce yourselves however you wish. To the extent that I feel it necessary, I will prod you if I feel you've left something out that I think is important, which is one of the prerogatives of the moderator. [Laughs] Other than that, it's pretty loose going around the table—and this will be the order in which we'll also speak—Chuck Neblett, Hollis Watkins, Worth Long, Candie Carawan, Bettie Mae Fikes. I could say things like, from Carbondale, Illinois and Mississippi and Worth Long: Atlanta. Cobb: Durham, North Carolina. Tennessee and Alabama, I'm not gonna do all of that. You all can give whatever geographical description of yourself within the context of discussing the music. What I do want in this first round is, since all of you are important voices in terms of music and culture in the Movement—to talk about how you made your way to the Freedom Singers and freedom singing. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season

INFANTRY HALL PROVIDENCE >©§to! Thirty-fifth Season, 1915-1916 Dr. KARL MUCK, Conductor WITH HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE NOTES BY PHILIP HALE TUESDAY EVENING, DECEMBER 28 AT 8.15 COPYRIGHT, 1915, BY C. A. ELLIS PUBLISHED BY C. A. ELLIS. MANAGER ii^^i^"""" u Yes, Ifs a Steinway" ISN'T there supreme satisfaction in being able to say that of the piano in your home? Would you have the same feeling about any other piano? " It's a Steinway." Nothing more need be said. Everybody knows you have chosen wisely; you have given to your home the very best that money can buy. You will never even think of changing this piano for any other. As the years go by the words "It's a Steinway" will mean more and more to you, and thousands of times, as you continue to enjoy through life the com- panionship of that noble instrument, absolutely without a peer, you will say to yourself: "How glad I am I paid the few extr? dollars and got a Steinway." STEINWAY HALL 107-109 East 14th Street, New York Subway Express Station at the Door Represented by the Foremost Dealers Everywhere 2>ympif Thirty-fifth Season,Se 1915-1916 Dr. KARL MUC per; \l iCs\l\-A Violins. Witek, A. Roth, 0. Hoffmann, J. Rissland, K. Concert-master. Koessler, M. Schmidt, E. Theodorowicz, J. Noack, S. Mahn, F. Bak, A. Traupe, W. Goldstein, H. Tak, E. Ribarsch, A. Baraniecki, A. Sauvlet, H. Habenicht, W. Fiedler, B. Berger, H. Goldstein, S. Fiumara, P. Spoor, S. Stilzen, H. Fiedler, A. -

Piano Trio in B Minor! Charles Edward Horsley!

! DIGITAL MUSIC ARCHIVE! ! Australian Music Series — MDA006! ! ! ! ! ! ! Piano Trio in B Minor! Opus 13 — 1848! ! ! ! ! Charles Edward Horsley! 1822 – 1876! ! ! ! Edited by! Richard Divall! ! ! ! ! ! Music Archive Monash University! Melbourne ! Information about the MUSIC ARCHIVE digital series ! Australian Music ! and other available works in free digital edition is available at ! http://artsonline.monash!.edu.au/music-archive! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! This edition may be used free of charge for private performance and study. ! It may be freely transmitted and copied in electronic or printed form. ! All rights are reserved for performance, recording, broadcast and publication in any !audio format.! ! ! !© 2013 Richard Divall! Published by ! MUSIC ARCHIVE OF MONASH UNIVERSITY! Sir Zelman Cowen School of Music ! !Monash University, Victoria 3800, Australia ! ! ISBN!978-0-9923956-5- 0! !ISMN!979-0-9009642 -5-0! ! The edition has been produced with generous assistance from the! Marshall-Hall Trust ! ! ! !3 Introduction Charles Edward Horsley was born in London in 1822 and died in New York in 1876. He came from an intensely musical family, and his father William Horsley, also a composer was a close family friend of Felix Mendelssohn and others. Horsley evinced a great musical talent early in life, and he studied in London with Mendelssohn, and Ignaz Moscheles, Franz Liszt’s own teacher. He later continued studies first in Kassel, and then in Leipzig with the above composers and also composition with Louis Spohr. The Editor has found over 170 compositions by Horsley and edited most of these already, including three symphonies, the piano and violin concertos, two string quartets, two piano trios, several sonatas and many lieder and works for piano solo. -

Sub-Group Ii—Thematic Arrangement

U.S. SHEET MUSIC COLLECTION SUB-GROUP II—THEMATIC ARRANGEMENT Consists of vocal and instrumental sheet music organized by designated special subjects. The materials have been organized variously within each series: in certain series, the music is arranged according to the related individual, corporate group, or topic (e.g., Personal Names, Corporate, and Places). The series of local imprints has been arranged alphabetically by composer surname. A full list of designated subjects follows: ______________________________________________________________________________ Patriotic Leading national songs . BOX 458 Other patriotic music, 1826-1899 . BOX 459 Other patriotic music, 1900– . BOX 460 National Government Presidents . BOX 461 Other national figures . BOX 462 Revolutionary War; War of 1812 . BOX 463 Mexican War . BOX 464 Civil War . BOXES 465-468 Spanish-American War . BOX 469 World War I . BOXES 470-473 World War II . BOXES 474-475 Personal Names . BOXES 476-482 Corporate Colleges and universities; College fraternities and sororities . BOX 483 Commercial entities . BOX 484 1 Firemen; Fraternal orders; Women’s groups; Militia groups . BOX 485 Musical groups; Other clubs . BOX 486 Places . BOXES 487-493 Events . BOX 494 Local Imprints Buffalo and Western New York imprints . BOXES 495-497 Other New York state and Pennsylvania imprints . BOX 498 Rochester imprints . BOXES 499-511 ______________________________________________________________________________ 2 U.S. Sheet Music Collection Ruth T. Watanabe Special Collections, Sibley Music Library Sub-Group II PATRIOTIC SERIES Leading National Songs Box 458 Ascher, Gustave, arr. America: My Country Tis of Thee. For voice and piano. In National Songs. New York: S. T. Gordon, 1861. Carey, Henry, arr. America: The United States National Anthem.