Journal 17Th Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Ethnographic Study of Sectarian Negotiations Among Diaspora Jains in the USA Venu Vrundavan Mehta Florida International University, [email protected]

Florida International University FIU Digital Commons FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations University Graduate School 3-29-2017 An Ethnographic Study of Sectarian Negotiations among Diaspora Jains in the USA Venu Vrundavan Mehta Florida International University, [email protected] DOI: 10.25148/etd.FIDC001765 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd Part of the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Mehta, Venu Vrundavan, "An Ethnographic Study of Sectarian Negotiations among Diaspora Jains in the USA" (2017). FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3204. https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/etd/3204 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the University Graduate School at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in FIU Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FLORIDA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY Miami, Florida AN ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY OF SECTARIAN NEGOTIATIONS AMONG DIASPORA JAINS IN THE USA A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in RELIGIOUS STUDIES by Venu Vrundavan Mehta 2017 To: Dean John F. Stack Steven J. Green School of International and Public Affairs This thesis, written by Venu Vrundavan Mehta, and entitled An Ethnographic Study of Sectarian Negotiations among Diaspora Jains in the USA, having been approved in respect to style and intellectual content, is referred to you for judgment. We have read this thesis and recommend that it be approved. ______________________________________________ Albert Kafui Wuaku ______________________________________________ Iqbal Akhtar ______________________________________________ Steven M. Vose, Major Professor Date of Defense: March 29, 2017 This thesis of Venu Vrundavan Mehta is approved. -

Indian Archaeology 1972-73

INDIAN ARCHAEOLOGY 1972-73 —A REVIEW EDITED BY M. N. DESHPANDE Director General Archaeological Survey of India ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA GOVERNMENT OF INDIA NEW DELHI 1978 Cover Recently excavated caskets from Piprahwa 1978 ARCHAEOLOGICAL SURVEY OF INDIA GOVERNMENT OF INDIA Price : Rs. 40.00 PRINTED AT NABA MUDRAN PRIVATE LTD., CALCUTTA, 700004 PREFACE Due to certain unavoidable reasons, the publication of the present issue has been delayed, for which I crave the indulgence of the readers. At the same time, I take this opportunity of informing the readers that the issue for 1973-74 is already in the Press and those for 1974-75 and 1975-76 are press-ready. It is hoped that we shall soon be up to date in the publication of the Review. As already known, the Review incorporates all the available information on the varied activities in the field of archaeology in the country and as such draws heavily on the contributions made by the organizations outside the Survey as well, viz. the Universities and other Research Institutions, including the Physical Research Laboratory, Ahmadabad and the Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeobotany, Lucknow, and the State Departments of Archaeology. My grateful thanks are due to all contributors, including my colleagues in the Survey, who supplied the material embodied in the Review as also helped me in editing and seeing it through the Press. M. N. DESHPANDE New Delhi 1 October 1978 CONTENTS PAGE I. Explorations and Excavations ... ... ... ... ... ... ... 1 Andhra Pradesh, 1; Arunachal, 3; Bihar, 3; Delhi, 8; Gujarat, 9; Haryana, 12; Jammu and Kashmir, 13; Kerala, 14; Madhya Pradesh, 14; Maharashtra, 20; Mysore, 25; Orissa, 27; Punjab, 28; Rajasthan, 28; Tamil Nadu, 30; Uttar Pradesh, 33; West Bengal, 35. -

Particulars of Some Temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of Some

Particulars of some temples of Kerala Contents Particulars of some temples of Kerala .............................................. 1 Introduction ............................................................................................... 9 Temples of Kerala ................................................................................. 10 Temples of Kerala- an over view .................................................... 16 1. Achan Koil Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 23 2. Alathiyur Perumthiri(Hanuman) koil ................................. 24 3. Randu Moorthi temple of Alathur......................................... 27 4. Ambalappuzha Krishnan temple ........................................... 28 5. Amedha Saptha Mathruka Temple ....................................... 31 6. Ananteswar temple of Manjeswar ........................................ 35 7. Anchumana temple , Padivattam, Edapalli....................... 36 8. Aranmula Parthasarathy Temple ......................................... 38 9. Arathil Bhagawathi temple ..................................................... 41 10. Arpuda Narayana temple, Thirukodithaanam ................. 45 11. Aryankavu Dharma Sastha ...................................................... 47 12. Athingal Bhairavi temple ......................................................... 48 13. Attukkal BHagawathy Kshethram, Trivandrum ............. 50 14. Ayilur Akhileswaran (Shiva) and Sri Krishna temples ........................................................................................................... -

SACRED SPACES and OBJECTS: the VISUAL, MATERIAL, and TANGIBLE George Pati

SACRED SPACES AND OBJECTS: THE VISUAL, MATERIAL, AND TANGIBLE George Pati BRAUER MUSEUM OF ART | APRIL 13 — MAY 8, 2016 WE AT THE BRAUER MUSEUM are grateful for the opportunity to present this exhibition curated by George Pati, Ph.D., Surjit S. Patheja Chair in World Religions and Ethics and Valparaiso University associate professor of theology and international studies. Through this exhibition, Professor Pati shares the fruits of his research conducted during his recent sabbatical and in addition provides valuable insights into sacred objects, sites, and practices in India. Professor Pati’s photographs document specific places but also reflect a creative eye at work; as an artist, his documents are also celebrations of the particular spaces that inspire him and capture his imagination. Accompanying the images in the exhibition are beautiful textiles and objects of metalware that transform the gallery into its own sacred space, with respectful and reverent viewing becoming its own ritual that could lead to a fuller understanding of the concepts Pati brings to our attention. Professor Pati and the Brauer staff wish to thank the Surjit S. Patheja Chair in World Religions and Ethics and the Partners for the Brauer Museum of Art for support of this exhibition. In addition, we wish to thank Gretchen Buggeln and David Morgan for the insights and perspectives they provide in their responses to Pati's essay and photographs. Gregg Hertzlieb, Director/Curator Brauer Museum of Art 2 | BRAUER MUSEUM OF ART SACRED SPACES AND OBJECTS: THE VISUAL, MATERIAL, AND TANGIBLE George Pati George Pati, Ph.D., Valparaiso University Śvetāśvatara Upaniṣad 6:23 Only in a man who has utmost devotion for God, and who shows the same devotion for teacher as for God, These teachings by the noble one will be illuminating. -

Circumambulation in Indian Pilgrimage: Meaning And

232 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC & ENGINEERING RESEARCH, VOLUME 12, ISSUE 1, JANUARY-2021 ISSN 2229-5518 Circumambulation in Indian pilgrimage: Meaning and manifestation Santosh Kumar Abstract— Our ancient literature is full of examples where pilgrimage became an immensely popular way of achieving spiritual aims while walking. In India, many communities have attached spiritual importance to particular places or to the place where people feel a spiritual awakening. Circumambulation (pradakshina) around that sacred place becomes the key point of prayer and offering. All these circumambulation spaces are associated with the shrines or sacred places referring to auspicious symbolism. In Indian tradition, circumambulation has been practice in multiple scales ranging from a deity or tree to sacred hill, river, and city. The spatial character of the path, route, and street, shift from an inside dwelling to outside in nature or city, depending upon the central symbolism. The experience of the space while walking through sacred space remodel people's mental and physical character. As a result, not only the sacred space but their design and physical characteristics can be both meaningful and valuable to the public. This research has been done by exploring in two stage to finalize the conclusion, In which First stage will involve a literature exploration of Hindu and Buddhist scripture to understand the meaning and significance of circumambulation and in second, will investigate the architectural manifestation of various element in circumambulatory which help to attain its meaning and true purpose. Index Terms— Pilgrimage, Circumambulation, Spatial, Sacred, Path, Hinduism, Temple architecture —————————— —————————— 1 Introduction Circumambulation ‘Pradakshinā’, According to Rig Vedic single light source falling upon central symbolism plays a verses1, 'Pra’ used as a prefix to the verb and takes on the vital role. -

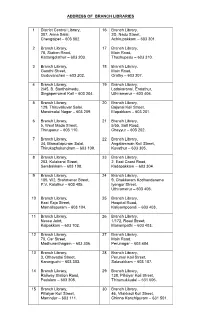

Branch Libraries List

ADDRESS OF BRANCH LIBRARIES 1 District Central Library, 16 Branch Library, 307, Anna Salai, 2D, Nadu Street, Chengalpet – 603 002. Achirupakkam – 603 301. 2 Branch Library, 17 Branch Library, 78, Station Road, Main Road, Kattangolathur – 603 203. Thozhupedu – 603 310. 3 Branch Library, 18 Branch Library, Gandhi Street, Main Road, Guduvancheri – 603 202. Orathy – 603 307. 4 Branch Library, 19 Branch Library, 2/45, B. Santhaimedu, Ladakaranai, Endathur, Singaperrumal Koil – 603 204. Uthiramerur – 603 406. 5 Branch Library, 20 Branch Library, 129, Thiruvalluvar Salai, Bajanai Koil Street, Maraimalai Nagar – 603 209. Elapakkam – 603 201. 6 Branch Library, 21 Branch Library, 5, West Mada Street, 5/55, Salt Road, Thiruporur – 603 110. Cheyyur – 603 202. 7 Branch Library, 22 Branch Library, 34, Mamallapuram Salai, Angalamman Koil Street, Thirukazhukundram – 603 109. Kuvathur – 603 305. 8 Branch Library, 23 Branch Library, 203, Kulakarai Street, 2, East Coast Road, Sembakkam – 603 108. Kadapakkam – 603 304. 9 Branch Library, 24 Branch Library, 105, W2, Brahmanar Street, 9, Chakkaram Kodhandarama P.V. Kalathur – 603 405. Iyengar Street, Uthiramerur – 603 406. 10 Branch Library, 25 Branch Library, East Raja Street, Hospital Road, Mamallapuram – 603 104. Kaliyampoondi – 603 403. 11 Branch Library, 26 Branch Library, Nesco Joint, 1/172, Road Street, Kalpakkam – 603 102. Manampathi – 603 403. 12 Branch Library, 27 Branch Library, 70, Car Street, Main Road, Madhuranthagam – 603 306. Perunagar – 603 404. 13 Branch Library, 28 Branch Library, 3, Othavadai Street, Perumal Koil Street, Karunguzhi – 603 303. Salavakkam – 603 107. 14 Branch Library, 29 Branch Library, Railway Station Road, 138, Pillaiyar Koil Street, Padalam – 603 308. -

Sources of Maratha History: Indian Sources

1 SOURCES OF MARATHA HISTORY: INDIAN SOURCES Unit Structure : 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Maratha Sources 1.3 Sanskrit Sources 1.4 Hindi Sources 1.5 Persian Sources 1.6 Summary 1.7 Additional Readings 1.8 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES After the completion of study of this unit the student will be able to:- 1. Understand the Marathi sources of the history of Marathas. 2. Explain the matter written in all Bakhars ranging from Sabhasad Bakhar to Tanjore Bakhar. 3. Know Shakavalies as a source of Maratha history. 4. Comprehend official files and diaries as source of Maratha history. 5. Understand the Sanskrit sources of the Maratha history. 6. Explain the Hindi sources of Maratha history. 7. Know the Persian sources of Maratha history. 1.1 INTRODUCTION The history of Marathas can be best studied with the help of first hand source material like Bakhars, State papers, court Histories, Chronicles and accounts of contemporary travelers, who came to India and made observations of Maharashtra during the period of Marathas. The Maratha scholars and historians had worked hard to construct the history of the land and people of Maharashtra. Among such scholars people like Kashinath Sane, Rajwade, Khare and Parasnis were well known luminaries in this field of history writing of Maratha. Kashinath Sane published a mass of original material like Bakhars, Sanads, letters and other state papers in his journal Kavyetihas Samgraha for more eleven years during the nineteenth century. There is much more them contribution of the Bharat Itihas Sanshodhan Mandal, Pune to this regard. -

Action Plan Manali12092016.Pdf

Sl. PAGE No No CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Area Details 1 1.2 Location 1 1.3 Digitized map with Demarcation of Geographical Boundaries and Impact Zones 1.4 CEPI Score 2 1.5 Total Population and Sensitive Receptors 2 1.6 Eco-geological features 4 1.6.1 Major Water bodies 4 1.6.2 Ecological parks , Sanctuaries , flora and fauna or any 4 ecosystem 1.6.3 Buildings or Monuments of Historical / 4 archaeological / religious importance 1.7 Industry Classification 5 1.7.1 Highly Polluting Industries 5 1.7.2 Red category industries 6 1.7.3 Orange and Green category industries 6 1.7.4 Grossly Polluting Industries 6 2 WATER ENVIRONMENT 2.1 Present status of water environment 7 2.1.1 Water bodies 7 2.1.2 Present level of pollutants 7 2.1.3 Predominant sources contributing to various 8 pollutant 2.2 Source of Water Pollution 8 2.2.1 Industrial 9 2.2.2 Domestic 9 2.2.3 Others 11 2.2.4 Impact on surrounding area 11 2.3 Details of water polluting industries in the area 11 cluster 2.4 Effluent Disposal Methods- Recipient water bodies 14 2.5 Quantification of wastewater pollution load and relative 17 contribution by different sources viz industrial/ domestic 2.6 Action Plan for compliance and control of Pollution 25 2.6.1 Existing infrastructure facilities 25 2.6.2 Pollution control measures installed by the units 26 2.6.3 Technological Intervention 36 2.6.4 Infrastructural Renewal 37 2.6.5 Managerial and financial aspects 37 2.6.6 Self monitoring system in industries 37 2.6.7 Data linkages to SPCB (of monitoring devices) 37 3 AIR ENVIRONMENT 3.1 Present -

History of Thirukolur and Vaithamanidhi Perumal Temple in Tiruchendur Taluk

© 2020 February 2020, Volume 7, Issue 2 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) HISTORY OF THIRUKOLUR AND VAITHAMANIDHI PERUMAL TEMPLE IN TIRUCHENDUR TALUK K.REVATHI Ph.D Research Scholar,(Part Time) Department of History, V.O. Chidambaram College, Affiliated to Manonmaniam Sundaranar University, Tirunelveli, Tamil Nadu, South India – 627012. Abstract As the God fearing people, the Tamils never preferred to settle in villages which had no temple and considered such villages as haunted places and unfit for human inhabitation. The temple is a place where God dwells in various forms embodied in sacred images or Symbols of deities which constitute the most important part of Hindu art. The images that were formed under the trees became temples made consequently on bricks being used for constructing temples. Since then several kinds of temples have come into existence. Silapathikaram contains reference about Vishnu temple. The Sixth and Seventh centuries A.D. was marked by the adoption of stone as medium by the Hindu and Jains of South India. The temples of South India still survive in thousands and are in use and maintain their importance and sanctity. The contributing factors for the state of the South Indian temple are the comparative freedom from foreign invasions and disruption in peninsular India, the strength and stability of the Kingdoms. The great empires of the South, the Chalukyas the Pallavas, the early Pandyas, the later cholas and the later Pandyas extended their patronage for the construction of the temples. KeyWords: TenTiruperai, Navathirupathi, Thirukolur, Vaithamanithi temple. Introduction History of Pandya country, Karaikudi, 1962.7. Jagadesan, N.,History of Srivaishnavism in Tamil Country, (Post Ramanuja), Madurai, 1977 Tiruchendurregion sustained and nurtured ancient civilization for many centuries that man can remember. -

Dr. Muhammad Hameed

Dr. Muhammad Hameed Chairman Associate Professor Department of Archaeology University of the Punjab (Archaeologist, Historian, Museologist, Field Expert, Heritage Expert) Profile Completed MA in Archaeology from University of the Punjab in 2004. Dr. Hameed joined Department of Archaeology, University of the Punjab as Lecturer in 2006. After serving the university for five years and getting overseas scholarship, he went to Berlin, Germany and completed his PHD in Gandhara Art, in 2015 from Free University Berlin. During his stay in Berlin, got several opportunity to become a part of the international research circle and attended international conferences, symposiums and workshops, about different aspects of South Asian Archaeology, held in Paris, Stockholm, Berlin, and Torun. The main research focuses on Buddhist Art with special interest in the Miniature Portable Shrines from Gandhara and Kashmir. The PHD dissertation provides the first catalogue of these objects. Study of origin of miniature portable shrines, their, types, iconography and religious significance are the main features of my research. Articles related to research areas have been published in HEC recognized journals as well as in international journals. Personal Info S/O: Muhammad Rafique DOB: 16-09-1981 NIC: 35401-9809372-3 Domicile: Sheikhupura (Punjab) Nationality: Pakistani Contact Info Off.: 042-99230322 Mobile: 03344063481 Email: [email protected] [email protected] Address: Department of Archaeology, University of the Punjab, Lahore Pakistan Experience February -

Catholic Shrines in Chennai, India: the Politics of Renewal and Apostolic Legacy

CATHOLIC SHRINES IN CHENNAI, INDIA: THE POLITICS OF RENEWAL AND APOSTOLIC LEGACY BY THOMAS CHARLES NAGY A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Religious Studies Victoria University of Wellington (2014) Abstract This thesis investigates the phenomenon of Catholic renewal in India by focussing on various Roman Catholic churches and shrines located in Chennai, a large city in South India where activities concerning saintal revival and shrinal development have taken place in the recent past. The thesis tracks the changing local significance of St. Thomas the Apostle, who according to local legend, was martyred and buried in Chennai. In particular, it details the efforts of the Church hierarchy in Chennai to bring about a revival of devotion to St. Thomas. In doing this, it covers a wide range of issues pertinent to the study of contemporary Indian Christianity, such as Indian Catholic identity, Indian Christian indigeneity and Hindu nationalism, as well as the marketing of St. Thomas and Catholicism within South India. The thesis argues that the Roman Catholic renewal and ―revival‖ of St. Thomas in Chennai is largely a Church-driven hierarchal movement that was specifically initiated for the purpose of Catholic evangelization and missionization in India. Furthermore, it is clear that the local Church‘s strategy of shrinal development and marketing encompasses Catholic parishes and shrines throughout Chennai‘s metropolitan area, and thus, is not just limited to those sites associated with St. Thomas‘s Apostolic legacy. i Acknowledgements This thesis is dedicated to the memory of my father Richard M. -

Updtd-Excel List of Doctors-2020.Xlsx

State / UT wise List of Doctors / Institution, authorised to issue Compulsory Health Certificate (for Shri Amarnathji Yatra 2020) Tamil Nadu Resident Medical Officers of the Medical College Hospitals under the control of Director of Medical Education,Chennai, Tamil Nadu mentioned below have been authorised to issue Compulory Health Certificate for the pilgrims of Shri Amarnathji Yqatra 2020 S.No District District Hospital Name of the Residential Phone / Mobile Medical Officer 1 Chennai Rajiv Gandhi Govt. Gen. Dr.Thirunavukkarasu S.K 9445030800 Hospital, Chennai 2 Govt. Stanley Hospital, Dr. Ramesh .M 98417-36989 Chennai 3 Kilpauk Medical College Dr. S. Rajakumar S 98842-26062 Hospital, Chennai 4 Institute of Mental Dr.Sumathi.S (I/C) 9677093145 Health, Chennai. 5 ISO &Govt.Kasturbna Dr.Elangovan S V 9840716412 Gandhi Hospital for Women & Children Chenai 6 Institute of Obstetrics Dr.Fatima (I/C) 7845500129 and Gyanecology and Govt.Hospital for Women & Children Chenai 7 Govt.Royapeetah Dr.Ananda Pratap M 9840053614 Hospital, Chennai 8 Institute of ChildHealth, Dr.Venkatesan (I/C) 8825540529 & Hospital for Children,Chennai-8 9 RIO & Govt. Opthalmic Dr.Senthil B 9381041296 Hospital, Chennai-8 10 Chengalpattu Chengalpattu Medical Dr. Valliarasi (I/c) 9944337807 College & Hospital,, Chengalpattu 11 thanjavur Thanjavur Medical Dr. Selvam 9443866578 , 9789382751 College & Hospital. thanjavur 12 Madurai Goverment Rajaji Dr. Sreelatha A. 9994793321 Hospital, Madurai 13 Coimbatore Coimbatore Medical Dr.Soundravel R 9842246171 College & Hospital 14 Salem Govt. Mohan Dr. Rani 9443246286 Kumaramangalam Medical College Hospital, Salem 15 Tirunelveli Tirunelveli Medical Dr. Shyam Sunder Singh N 9965580770 College & Hospital 16 Trichy Mahatma Gandhi Dr.Chandran (I/C) 9043500045 Memorial & Hospital, Trichy 17 Tuticorin Thoothukudi Medical Dr.Silesh Jayamani 9865131079 College & Hospital, Thoothukudi 18 Kanya kumari Govt.