N-Dimensional Euclidean Space and Matrices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glossary Physics (I-Introduction)

1 Glossary Physics (I-introduction) - Efficiency: The percent of the work put into a machine that is converted into useful work output; = work done / energy used [-]. = eta In machines: The work output of any machine cannot exceed the work input (<=100%); in an ideal machine, where no energy is transformed into heat: work(input) = work(output), =100%. Energy: The property of a system that enables it to do work. Conservation o. E.: Energy cannot be created or destroyed; it may be transformed from one form into another, but the total amount of energy never changes. Equilibrium: The state of an object when not acted upon by a net force or net torque; an object in equilibrium may be at rest or moving at uniform velocity - not accelerating. Mechanical E.: The state of an object or system of objects for which any impressed forces cancels to zero and no acceleration occurs. Dynamic E.: Object is moving without experiencing acceleration. Static E.: Object is at rest.F Force: The influence that can cause an object to be accelerated or retarded; is always in the direction of the net force, hence a vector quantity; the four elementary forces are: Electromagnetic F.: Is an attraction or repulsion G, gravit. const.6.672E-11[Nm2/kg2] between electric charges: d, distance [m] 2 2 2 2 F = 1/(40) (q1q2/d ) [(CC/m )(Nm /C )] = [N] m,M, mass [kg] Gravitational F.: Is a mutual attraction between all masses: q, charge [As] [C] 2 2 2 2 F = GmM/d [Nm /kg kg 1/m ] = [N] 0, dielectric constant Strong F.: (nuclear force) Acts within the nuclei of atoms: 8.854E-12 [C2/Nm2] [F/m] 2 2 2 2 2 F = 1/(40) (e /d ) [(CC/m )(Nm /C )] = [N] , 3.14 [-] Weak F.: Manifests itself in special reactions among elementary e, 1.60210 E-19 [As] [C] particles, such as the reaction that occur in radioactive decay. -

Interval Notation and Linear Inequalities

CHAPTER 1 Introductory Information and Review Section 1.7: Interval Notation and Linear Inequalities Linear Inequalities Linear Inequalities Rules for Solving Inequalities: 86 University of Houston Department of Mathematics SECTION 1.7 Interval Notation and Linear Inequalities Interval Notation: Example: Solution: MATH 1300 Fundamentals of Mathematics 87 CHAPTER 1 Introductory Information and Review Example: Solution: Example: 88 University of Houston Department of Mathematics SECTION 1.7 Interval Notation and Linear Inequalities Solution: Additional Example 1: Solution: MATH 1300 Fundamentals of Mathematics 89 CHAPTER 1 Introductory Information and Review Additional Example 2: Solution: 90 University of Houston Department of Mathematics SECTION 1.7 Interval Notation and Linear Inequalities Additional Example 3: Solution: Additional Example 4: Solution: MATH 1300 Fundamentals of Mathematics 91 CHAPTER 1 Introductory Information and Review Additional Example 5: Solution: Additional Example 6: Solution: 92 University of Houston Department of Mathematics SECTION 1.7 Interval Notation and Linear Inequalities Additional Example 7: Solution: MATH 1300 Fundamentals of Mathematics 93 Exercise Set 1.7: Interval Notation and Linear Inequalities For each of the following inequalities: Write each of the following inequalities in interval (a) Write the inequality algebraically. notation. (b) Graph the inequality on the real number line. (c) Write the inequality in interval notation. 23. 1. x is greater than 5. 2. x is less than 4. 24. 3. x is less than or equal to 3. 4. x is greater than or equal to 7. 25. 5. x is not equal to 2. 6. x is not equal to 5 . 26. 7. x is less than 1. 8. -

1 Euclidean Vector Space and Euclidean Affi Ne Space

Profesora: Eugenia Rosado. E.T.S. Arquitectura. Euclidean Geometry1 1 Euclidean vector space and euclidean a¢ ne space 1.1 Scalar product. Euclidean vector space. Let V be a real vector space. De…nition. A scalar product is a map (denoted by a dot ) V V R ! (~u;~v) ~u ~v 7! satisfying the following axioms: 1. commutativity ~u ~v = ~v ~u 2. distributive ~u (~v + ~w) = ~u ~v + ~u ~w 3. ( ~u) ~v = (~u ~v) 4. ~u ~u 0, for every ~u V 2 5. ~u ~u = 0 if and only if ~u = 0 De…nition. Let V be a real vector space and let be a scalar product. The pair (V; ) is said to be an euclidean vector space. Example. The map de…ned as follows V V R ! (~u;~v) ~u ~v = x1x2 + y1y2 + z1z2 7! where ~u = (x1; y1; z1), ~v = (x2; y2; z2) is a scalar product as it satis…es the …ve properties of a scalar product. This scalar product is called standard (or canonical) scalar product. The pair (V; ) where is the standard scalar product is called the standard euclidean space. 1.1.1 Norm associated to a scalar product. Let (V; ) be a real euclidean vector space. De…nition. A norm associated to the scalar product is a map de…ned as follows V kk R ! ~u ~u = p~u ~u: 7! k k Profesora: Eugenia Rosado, E.T.S. Arquitectura. Euclidean Geometry.2 1.1.2 Unitary and orthogonal vectors. Orthonormal basis. Let (V; ) be a real euclidean vector space. De…nition. -

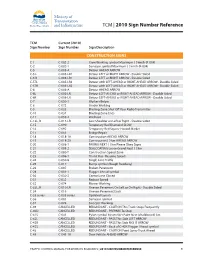

2010 Sign Number Reference for Traffic Control Manual

TCM | 2010 Sign Number Reference TCM Current (2010) Sign Number Sign Number Sign Description CONSTRUCTION SIGNS C-1 C-002-2 Crew Working symbol Maximum ( ) km/h (R-004) C-2 C-002-1 Surveyor symbol Maximum ( ) km/h (R-004) C-5 C-005-A Detour AHEAD ARROW C-5 L C-005-LR1 Detour LEFT or RIGHT ARROW - Double Sided C-5 R C-005-LR1 Detour LEFT or RIGHT ARROW - Double Sided C-5TL C-005-LR2 Detour with LEFT-AHEAD or RIGHT-AHEAD ARROW - Double Sided C-5TR C-005-LR2 Detour with LEFT-AHEAD or RIGHT-AHEAD ARROW - Double Sided C-6 C-006-A Detour AHEAD ARROW C-6L C-006-LR Detour LEFT-AHEAD or RIGHT-AHEAD ARROW - Double Sided C-6R C-006-LR Detour LEFT-AHEAD or RIGHT-AHEAD ARROW - Double Sided C-7 C-050-1 Workers Below C-8 C-072 Grader Working C-9 C-033 Blasting Zone Shut Off Your Radio Transmitter C-10 C-034 Blasting Zone Ends C-11 C-059-2 Washout C-13L, R C-013-LR Low Shoulder on Left or Right - Double Sided C-15 C-090 Temporary Red Diamond SLOW C-16 C-092 Temporary Red Square Hazard Marker C-17 C-051 Bridge Repair C-18 C-018-1A Construction AHEAD ARROW C-19 C-018-2A Construction ( ) km AHEAD ARROW C-20 C-008-1 PAVING NEXT ( ) km Please Obey Signs C-21 C-008-2 SEALCOATING Loose Gravel Next ( ) km C-22 C-080-T Construction Speed Zone C-23 C-086-1 Thank You - Resume Speed C-24 C-030-8 Single Lane Traffic C-25 C-017 Bump symbol (Rough Roadway) C-26 C-007 Broken Pavement C-28 C-001-1 Flagger Ahead symbol C-30 C-030-2 Centre Lane Closed C-31 C-032 Reduce Speed C-32 C-074 Mower Working C-33L, R C-010-LR Uneven Pavement On Left or On Right - Double Sided C-34 -

Interval Computations: Introduction, Uses, and Resources

Interval Computations: Introduction, Uses, and Resources R. B. Kearfott Department of Mathematics University of Southwestern Louisiana U.S.L. Box 4-1010, Lafayette, LA 70504-1010 USA email: [email protected] Abstract Interval analysis is a broad field in which rigorous mathematics is as- sociated with with scientific computing. A number of researchers world- wide have produced a voluminous literature on the subject. This article introduces interval arithmetic and its interaction with established math- ematical theory. The article provides pointers to traditional literature collections, as well as electronic resources. Some successful scientific and engineering applications are listed. 1 What is Interval Arithmetic, and Why is it Considered? Interval arithmetic is an arithmetic defined on sets of intervals, rather than sets of real numbers. A form of interval arithmetic perhaps first appeared in 1924 and 1931 in [8, 104], then later in [98]. Modern development of interval arithmetic began with R. E. Moore’s dissertation [64]. Since then, thousands of research articles and numerous books have appeared on the subject. Periodic conferences, as well as special meetings, are held on the subject. There is an increasing amount of software support for interval computations, and more resources concerning interval computations are becoming available through the Internet. In this paper, boldface will denote intervals, lower case will denote scalar quantities, and upper case will denote vectors and matrices. Brackets “[ ]” will delimit intervals while parentheses “( )” will delimit vectors and matrices.· Un- derscores will denote lower bounds of· intervals and overscores will denote upper bounds of intervals. Corresponding lower case letters will denote components of vectors. -

Higher Dimensional Conundra

Higher Dimensional Conundra Steven G. Krantz1 Abstract: In recent years, especially in the subject of harmonic analysis, there has been interest in geometric phenomena of RN as N → +∞. In the present paper we examine several spe- cific geometric phenomena in Euclidean space and calculate the asymptotics as the dimension gets large. 0 Introduction Typically when we do geometry we concentrate on a specific venue in a particular space. Often the context is Euclidean space, and often the work is done in R2 or R3. But in modern work there are many aspects of analysis that are linked to concrete aspects of geometry. And there is often interest in rendering the ideas in Hilbert space or some other infinite dimensional setting. Thus we want to see how the finite-dimensional result in RN changes as N → +∞. In the present paper we study some particular aspects of the geometry of RN and their asymptotic behavior as N →∞. We choose these particular examples because the results are surprising or especially interesting. We may hope that they will lead to further studies. It is a pleasure to thank Richard W. Cottle for a careful reading of an early draft of this paper and for useful comments. 1 Volume in RN Let us begin by calculating the volume of the unit ball in RN and the surface area of its bounding unit sphere. We let ΩN denote the former and ωN−1 denote the latter. In addition, we let Γ(x) be the celebrated Gamma function of L. Euler. It is a helpful intuition (which is literally true when x is an 1We are happy to thank the American Institute of Mathematics for its hospitality and support during this work. -

Glossary of Linear Algebra Terms

INNER PRODUCT SPACES AND THE GRAM-SCHMIDT PROCESS A. HAVENS 1. The Dot Product and Orthogonality 1.1. Review of the Dot Product. We first recall the notion of the dot product, which gives us a familiar example of an inner product structure on the real vector spaces Rn. This product is connected to the Euclidean geometry of Rn, via lengths and angles measured in Rn. Later, we will introduce inner product spaces in general, and use their structure to define general notions of length and angle on other vector spaces. Definition 1.1. The dot product of real n-vectors in the Euclidean vector space Rn is the scalar product · : Rn × Rn ! R given by the rule n n ! n X X X (u; v) = uiei; viei 7! uivi : i=1 i=1 i n Here BS := (e1;:::; en) is the standard basis of R . With respect to our conventions on basis and matrix multiplication, we may also express the dot product as the matrix-vector product 2 3 v1 6 7 t î ó 6 . 7 u v = u1 : : : un 6 . 7 : 4 5 vn It is a good exercise to verify the following proposition. Proposition 1.1. Let u; v; w 2 Rn be any real n-vectors, and s; t 2 R be any scalars. The Euclidean dot product (u; v) 7! u · v satisfies the following properties. (i:) The dot product is symmetric: u · v = v · u. (ii:) The dot product is bilinear: • (su) · v = s(u · v) = u · (sv), • (u + v) · w = u · w + v · w. -

Chapter 5 ANGULAR MOMENTUM and ROTATIONS

Chapter 5 ANGULAR MOMENTUM AND ROTATIONS In classical mechanics the total angular momentum L~ of an isolated system about any …xed point is conserved. The existence of a conserved vector L~ associated with such a system is itself a consequence of the fact that the associated Hamiltonian (or Lagrangian) is invariant under rotations, i.e., if the coordinates and momenta of the entire system are rotated “rigidly” about some point, the energy of the system is unchanged and, more importantly, is the same function of the dynamical variables as it was before the rotation. Such a circumstance would not apply, e.g., to a system lying in an externally imposed gravitational …eld pointing in some speci…c direction. Thus, the invariance of an isolated system under rotations ultimately arises from the fact that, in the absence of external …elds of this sort, space is isotropic; it behaves the same way in all directions. Not surprisingly, therefore, in quantum mechanics the individual Cartesian com- ponents Li of the total angular momentum operator L~ of an isolated system are also constants of the motion. The di¤erent components of L~ are not, however, compatible quantum observables. Indeed, as we will see the operators representing the components of angular momentum along di¤erent directions do not generally commute with one an- other. Thus, the vector operator L~ is not, strictly speaking, an observable, since it does not have a complete basis of eigenstates (which would have to be simultaneous eigenstates of all of its non-commuting components). This lack of commutivity often seems, at …rst encounter, as somewhat of a nuisance but, in fact, it intimately re‡ects the underlying structure of the three dimensional space in which we are immersed, and has its source in the fact that rotations in three dimensions about di¤erent axes do not commute with one another. -

Scalar-Tensor Theories of Gravity: Some Personal History

history-st-cuba-slides 8:31 May 27, 2008 1 SCALAR-TENSOR THEORIES OF GRAVITY: SOME PERSONAL HISTORY Cuba meeting in Mexico 2008 Remembering Johnny Wheeler (JAW), 1911-2008 and Bob Dicke, 1916-1997 We all recall Johnny as one of the most prominent and productive leaders of relativ- ity research in the United States starting from the late 1950’s. I recall him as the man in relativity when I entered Princeton as a graduate student in 1957. One of his most recent students on the staff there at that time was Charlie Misner, who taught a really new, interesting, and, to me, exciting type of relativity class based on then “modern mathematical techniques involving topology, bundle theory, differential forms, etc. Cer- tainly Misner had been influenced by Wheeler to pursue these then cutting-edge topics and begin the re-write of relativity texts that ultimately led to the massive Gravitation or simply “Misner, Thorne, and Wheeler. As I recall (from long! ago) Wheeler was the type to encourage and mentor young people to investigate new ideas, especially mathe- matical, to develop and probe new insights into the physical universe. Wheeler himself remained, I believe, more of a “generalist, relying on experts to provide details and rigorous arguments. Certainly some of the world’s leading mathematical work was being done only a brief hallway walk away from Palmer Physical Laboratory to Fine Hall. Perhaps many are unaware that Bob Dicke had been an undergraduate student of Wheeler’s a few years earlier. It was Wheeler himself who apparently got Bob thinking about the foundations of Einstein’s gravitational theory, in particular, the ever present mysteries of inertia. -

Integrating Electrical Machines and Antennas Via Scalar and Vector Magnetic Potentials; an Approach for Enhancing Undergraduate EM Education

Integrating Electrical Machines and Antennas via Scalar and Vector Magnetic Potentials; an Approach for Enhancing Undergraduate EM Education Seemein Shayesteh Maryam Rahmani Lauren Christopher Maher Rizkalla Department of Electrical and Department of Electrical and Department of Electrical and Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering Computer Engineering Computer Engineering Computer Engineering Indiana University Purdue Indiana University Purdue Indiana University Purdue Indiana University Purdue University Indianapolis University Indianapolis University Indianapolis University Indianapolis Indianapolis, IN Indianapolis, IN Indianapolis, IN Indianapolis, IN [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract—This Innovative Practice Work In Progress paper undergraduate course. In one offering the course was attached presents an approach for enhancing undergraduate with a project using COMSOL software that assisted students Electromagnetic education. with better understanding of the differential EM equations within the course. Keywords— Electromagnetic, antennas, electrical machines, undergraduate, potentials, projects, ECE II. COURSE OUTLINE I. INTRODUCTION A. Typical EM Course within an ECE Curriculum Often times, the subject of using two potential functions in A typical EM undergraduate course requires Physics magnetism, the scalar magnetic potential function, ܸ, and the (electricity and magnetism) and Differential equations as pre- vector magnetic potential function, ܣ (with zero current requisite -

General Topology

General Topology Tom Leinster 2014{15 Contents A Topological spaces2 A1 Review of metric spaces.......................2 A2 The definition of topological space.................8 A3 Metrics versus topologies....................... 13 A4 Continuous maps........................... 17 A5 When are two spaces homeomorphic?................ 22 A6 Topological properties........................ 26 A7 Bases................................. 28 A8 Closure and interior......................... 31 A9 Subspaces (new spaces from old, 1)................. 35 A10 Products (new spaces from old, 2)................. 39 A11 Quotients (new spaces from old, 3)................. 43 A12 Review of ChapterA......................... 48 B Compactness 51 B1 The definition of compactness.................... 51 B2 Closed bounded intervals are compact............... 55 B3 Compactness and subspaces..................... 56 B4 Compactness and products..................... 58 B5 The compact subsets of Rn ..................... 59 B6 Compactness and quotients (and images)............. 61 B7 Compact metric spaces........................ 64 C Connectedness 68 C1 The definition of connectedness................... 68 C2 Connected subsets of the real line.................. 72 C3 Path-connectedness.......................... 76 C4 Connected-components and path-components........... 80 1 Chapter A Topological spaces A1 Review of metric spaces For the lecture of Thursday, 18 September 2014 Almost everything in this section should have been covered in Honours Analysis, with the possible exception of some of the examples. For that reason, this lecture is longer than usual. Definition A1.1 Let X be a set. A metric on X is a function d: X × X ! [0; 1) with the following three properties: • d(x; y) = 0 () x = y, for x; y 2 X; • d(x; y) + d(y; z) ≥ d(x; z) for all x; y; z 2 X (triangle inequality); • d(x; y) = d(y; x) for all x; y 2 X (symmetry). -

Properties of Euclidean Space

Section 3.1 Properties of Euclidean Space As has been our convention throughout this course, we use the notation R2 to refer to the plane (two dimensional space); R3 for three dimensional space; and Rn to indicate n dimensional space. Alternatively, these spaces are often referred to as Euclidean spaces; for example, \three dimensional Euclidean space" refers to R3. In this section, we will point out many of the special features common to the Euclidean spaces; in Chapter 4, we will see that many of these features are shared by other \spaces" as well. Many of the graphics in this section are drawn in two dimensions (largely because this is the easiest space to visualize on paper), but you should be aware that the ideas presented apply to n dimensional Euclidean space, not just to two dimensional space. Vectors in Euclidean Space When we refer to a vector in Euclidean space, we mean directed line segments that are embedded in the space, such as the vector pictured below in R2: We often refer to a vector, such as the vector AB shown below, by its initial and terminal points; in this example, A is the initial point of AB, and B is the terminal point of the vector. While we often think of n dimensional space as being made up of points, we may equivalently consider it to be made up of vectors by identifying points and vectors. For instance, we identify the point (2; 1) in two dimensional Euclidean space with the vector with initial point (0; 0) and terminal point (2; 1): 1 Section 3.1 In this way, we think of n dimensional Euclidean space as being made up of n dimensional vectors.