Ludomusicological Semiotics: Theory, Implications, and Case Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jeu-Xbox-360-Microsoft--Forza-Motorsport-4-Goty-Xbox-360--930138.Pdf

- Tout simplement magnifique, "Wow". - Gamekult, Juil 2011 Déjà considéré comme la référence en matière de simulation sur cette génération de console grâce à Forza 3, Microsoft livre un véritable chef d’œuvre à la Xbox 360 avec Forza Motorsport 4 ! Forza Motorsport 4 est le plus gros titre de la série à ce jour. Des centaines de voitures sensationnelles conçues par plus de quatre-vingts constructeurs automobiles différents. Les meilleurs circuits au monde. Une nouvelle façon révolutionnaire d'appréhender la conduite. Des fonctionnalités en ligne qui redéfinissent la communauté de Forza Motorsport. C'est l'endroit rêvé pour les passionnés de voitures. Caractéristiques et points forts La licence phares des jeux de courses sur Xbox 360 : Avec plus de 210 000 jeux Sortie : 14 octobre 2011 vendus sur FM3 en France (source GFK juillet 2011), Forza est la marque incontournable pour les fans de voitures. Forza 4 a déjà gagné de nombreuses Nbre Joueurs : 1-16 récompenses à l’E3 2001. Genre : course La référence pour tous : Que vous soyez un pilote expérimenté ou que vous débutiez, défis et divertissements sont au rendez-vous dans Forza Motorsport 4. Développeur : Turn10 Un large choix d'aides permet aux nouveaux pilotes de se faire rapidement la main et grâce au nouveau modèle physique et au nouveau mode carrière, les Éditeur : Microsoft pilotes invétérés peuvent paramétrer chaque voiture dans leur garage pour remporter la victoire. PEGI : 3+ Les fonctionnalités Kinect : 3 modes Kinect pour plaire au plus grand nombre : Gencode : - L’Autovista pour les passionnés d’automobiles : un véritable showroom pour Strd > 885370309959 découvrir au plus pres les plus belles voitures du monde Lmtd > 885370310160 - La conduite Kinect : au fond du canapé, placez vos mains à 10h10 et jouez en course arcade pour toute la famille, sans manette - Le headtracking : pour les puristes de la conduite, Kinect suivra vos Ref Sku : mouvements de têtes pour adapter la caméra du jeu. -

Einfluss Technischer Mittel Auf Die Kompostionsmethoden Von Jeremy Soule

Einfluss technischer Mittel auf die Kom- positionsmethoden von Jeremy Soule Andrea Giffinger Institut für Musikwissenschaft, Innsbruck Zusammenfassung Im folgenden Text werden einige der Kompositionsmethoden Jeremy Soules exemplarisch herausge- hoben. Es sollen dabei die verschiedenen Parameter aufgezeigt werden, die den kreativen Prozess eines Komponisten beeinflussen. Darüber hinaus wird auch auf einige der Probleme, mit denen er aufgrund der ihm zur Verfügung stehenden technischen Mittel konfrontiert wurde, eingegangen, sowie deren Lösung gezeigt. Am Ende werden Forschungsfragen im Bezug auf die Elder Scrolls Reihe gestellt. 1 Einleitung Computerspiele wurden bereits in den 1970er kommerziell vermarktet, die akademische For- schung allerdings beschäftigte sich erst in den späten 1990er eingehender mit diesem Medien- phänomen. Seitdem haben sich verschiedenste Disziplinen, die gemeinsam das Forschungsfeld der Video Game Studies bilden, auf analytischer Ebene mit Computerspielen auseinandergesetzt (Süß, 2006). Um die Musik in Computerspielen zu untersuchen, werden nicht selten Methoden der Analyse von Filmmusik angewandt. Jedoch bergen diese Gefahren, da es sich, im Gegen- satz zum Film, um ein interaktives Medium handelt. Je nach Genre bestimmt der Spieler den Ablauf der Musik, wobei ihre Wirkung wiederum Auswirkungen auf den Ablauf des Spiels ha- ben kann. Gerade in der Spielreihe Elder Scrolls III-V, deren von Jeremy Soule komponierte Musik Gegenstand meiner Forschung ist, erhält diese durch die offene Spielwelt einen perfor- mativen Aspekt. Die spärlich vorhandene Literatur über Musik in Computerspielen, der Mangel an geeigneten Analyse Theorien und die Tatsache, dass sie immer präsenter in den Konzertsälen wird, ist Anreiz sich mit diesem Thema intensiv zu beschäftigen. 2 Umgang mit technischen Mitteln Soule komponiert seit 1995 Musik für Computerspiele (Dean, 2013) wie Secret of Evermo- re Total Annihilation, Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic, die Harry Potter Reihe, Guild VeröffentlichtPlatzhalter für durch DOI die und Gesellschaft ggf. -

Videogames, Distinction and Subject-English: New Paradigms for Pedagogy

Videogames, distinction and subject-English: new paradigms for pedagogy Alexander Victor Bacalja ORCID identifier: 0000-0002-2440-148 Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May, 2017 Melbourne Graduate School of Education The University of Melbourne 1 Abstract At a time when the proliferation of videogame ownership and practice has led to greater attention on the consequences of increased engagement with these texts, schools and educators are engaged in active debate regarding their potential value and use. The distinctive nature of these texts, especially in contrast to those texts which have traditionally dominated school environments, has raised questions about their possible affordances, as well as the pedagogies most appropriate for supporting teaching with and through these texts in the classroom. While much has been written about the learning benefits of videogames, especially in terms of opportunities for the negotiation of self (Gee, 2003), there has been less research addressing the impact of applying existing English subject-specific pedagogies to their study. In particular, there are few case-study investigations into the suitability of subject-English classrooms for the play and study of videogames. The project utilised a naturalistic case-study intervention involving eight 15-year-old students at a co-educational school in the outer-Northern suburbs of Melbourne. Data was collected during a five- week intervention in an English classroom context at the participants’ home-school. This involved the teacher-researcher leading a series of learning and teaching activities informed by dominant models of subject-English (Cox, 1989), Cultural Heritage, Skills, Personal Growth, and Critical Literacy, that focussed on several popular videogames. -

The Role of Audio for Immersion in Computer Games

CAPTIVATING SOUND THE ROLE OF AUDIO FOR IMMERSION IN COMPUTER GAMES by Sander Huiberts Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD at the Utrecht School of the Arts (HKU) Utrecht, The Netherlands and the University of Portsmouth Portsmouth, United Kingdom November 2010 Captivating Sound The role of audio for immersion in computer games © 2002‐2010 S.C. Huiberts Supervisor: Jan IJzermans Director of Studies: Tony Kalus Examiners: Dick Rijken, Dan Pinchbeck 2 Whilst registered as a candidate for the above degree, I have not been registered for any other research award. The results and conclusions embodied in this thesis are the work of the named candidate and have not been submitted for any other academic award. 3 Contents Abstract__________________________________________________________________________________________ 6 Preface___________________________________________________________________________________________ 7 1. Introduction __________________________________________________________________________________ 8 1.1 Motivation and background_____________________________________________________________ 8 1.2 Definition of research area and methodology _______________________________________ 11 Approach_________________________________________________________________________________ 11 Survey methods _________________________________________________________________________ 12 2. Game audio: the IEZA model ______________________________________________________________ 14 2.1 Understanding the structure -

2004 February

February 2004 Games and Entertainment Megan Morrone Today you can use the same machine to organize your finances, create a presentation for your boss, and defend the Earth from flesh-eating aliens. But let’s be honest: Even with the crazy advances in software, organizing your finances and creating a presentation for your boss are still not half as much fun as defending the Earth from flesh-eating aliens.That’s why we’ve devoted the entire month of February to the noble pursuit of games and entertainment for PCs, Macs, game consoles, and PDAs. I know what you’re thinking.You’re thinking that you can skip right over this chapter because you’re not a gamer. Gamers are all sweaty, pimpled, 16-year-old boys who lock themselves in their basements sustained only by complex carbohydrates and Mountain Dew for days on end, right? Wrong.Video games aren’t just for young boys anymore. Saying you don’t like video games is like saying you don’t like ice cream or cheese or television or fun.Are you trying to tell me that you don’t like fun? If you watch The Screen Savers,you know that each member of our little TV family has a uniquely different interest in games. Morgan loves a good frag fest, whereas Martin’s tastes tend toward the bizarre (think frogs in blenders or cow tossing.) Kevin knows how to throw a cutting-edge LAN party,while Joshua and Roger like to kick back with old-school retro game emulators. I like to download free and simple low-res games that you can play on even the dinkiest PC, whereas Patrick prefers to build and rebuild the perfect system for the ultimate gaming experience (see February 13).And leave it to Leo to discover the most unique new gaming experience for the consummate early adopter (see February 1). -

Mapping Topographies in the Anglo and German Narratives of Joseph Conrad, Anna Seghers, James Joyce, and Uwe Johnson

MAPPING TOPOGRAPHIES IN THE ANGLO AND GERMAN NARRATIVES OF JOSEPH CONRAD, ANNA SEGHERS, JAMES JOYCE, AND UWE JOHNSON DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Kristy Rickards Boney, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2006 Dissertation Committee: Approved by: Professor Helen Fehervary, Advisor Professor John Davidson Professor Jessica Prinz Advisor Graduate Program in Professor Alexander Stephan Germanic Languages and Literatures Copyright by Kristy Rickards Boney 2006 ABSTRACT While the “space” of modernism is traditionally associated with the metropolis, this approach leaves unaddressed a significant body of work that stresses non-urban settings. Rather than simply assuming these spaces to be the opposite of the modern city, my project rejects the empty term space and instead examines topographies, literally meaning the writing of place. Less an examination of passive settings, the study of topography in modernism explores the action of creating spaces—either real or fictional which intersect with a variety of cultural, social, historical, and often political reverberations. The combination of charged elements coalesce and form a strong visual, corporeal, and sensory-filled topography that becomes integral to understanding not only the text and its importance beyond literary studies. My study pairs four modernists—two writing in German and two in English: Joseph Conrad and Anna Seghers and James Joyce and Uwe Johnson. All writers, having experienced displacement through exile, used topographies in their narratives to illustrate not only their understanding of history and humanity, but they also wrote narratives which concerned a larger global ii community. -

Analyzing Modular Smoothness in Video Game Music

Analyzing Modular Smoothness in Video Game Music Elizabeth Medina-Gray KEYWORDS: video game music, modular music, smoothness, probability, The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker, Portal 2 ABSTRACT: This article provides a detailed method for analyzing smoothness in the seams between musical modules in video games. Video game music is comprised of distinct modules that are triggered during gameplay to yield the real-time soundtracks that accompany players’ diverse experiences with a given game. Smoothness —a quality in which two convergent musical modules fit well together—as well as the opposite quality, disjunction, are integral products of modularity, and each quality can significantly contribute to a game. This article first highlights some modular music structures that are common in video games, and outlines the importance of smoothness and disjunction in video game music. Drawing from sources in the music theory, music perception, and video game music literature (including both scholarship and practical composition guides), this article then introduces a method for analyzing smoothness at modular seams through a particular focus on the musical aspects of meter, timbre, pitch, volume, and abruptness. The method allows for a comprehensive examination of smoothness in both sequential and simultaneous situations, and it includes a probabilistic approach so that an analyst can treat all of the many possible seams that might arise from a single modular system. Select analytical examples from The Legend of Zelda: The Wind Waker and Portal -

Ontic Communities

Ontic Communities: Speculative Fiction, Ontology, and the Digital Design Community A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Drexel University by James W. Malazita in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2014 ii © Copyright 2014 James W. Malazita. All Rights Reserved. iii Table of Contents Introduction:........................................................................................................................ 1 Chapter 1: Communities of Practice, Who and What:...................................................... 45 Chapter 2: Ontology and Epistemology:........................................................................... 93 Chapter 3: Speculative Reality:....................................................................................... 144 Conclusion:....................................................................................................................... 190 Works Cited:.....................................................................................................................192 iv List of Tables 1. Analysis of Speakers and Article Content of Wired .............................................................8 2. Analysis of Ontic Talk in Wired...................................................................................... ..109 v List of Figures 1. The Subject-Object Split in Social Scientific Thinking...............................................................27 2. A Screen Shot of Cipher Prime's Auditorium ............................................................................52 -

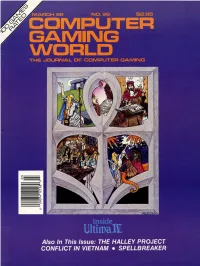

Computer Gaming World Issue 26

Number 26 March 1986 FEATURES Conflict In Viet Nam 14 The View From a Playtester M. Evan Brooks Inside Ultima IV 18 Interview with Lord British The Halley Project 24 Tooling Through the Solar System Gregg Williams Silent Service 28 Designer's Notes Sid Meier Star Trek: The Kobayashi Alternative 36 A Review Scorpia DEPARTMENTS Taking A Peek 6 Screen Photos and Brief Comments Scorpion's Tale 12 Playing Tips on SPELLBREAKER Scorpia Strategically Speaking 22 Game Playing Tips Atari Playfield 30 Koronis Rift and The Eidolon Gregg Williams Amiga Preferences 32 A New Column on the Amiga Roy Wagner Commodore Key 38 Flexidraw, Lode Runner's Rescue, and Little Computer People Roy Wagner The Learning Game 40 Story Tree Bob Proctor Over There 41! A New Column on British Games Leslie B. Bunder Reader Input Device 43 Game Ratings 48 100 Games Rated Accolade is rewarded with an excellent Artworx 20863 Stevens Creek Blvd graphics sequence. Joystick. 150 North Main Street Cupertino, CA 95014 One player. C-64, IBM. ($29.95 Fairport, NY 14450 408-446-5757 & $39.95). Circle Reader Service #4 800-828-6573 FIGHT NIGHT: Arcade style Activision FP II: With Falcon Patrol 2 the boxing game. A choice of six 2350 Bayshore Frontage Road player controls a fighter plane different contenders to battle Mountain View, CA 94043 equipped with the latest mis- for the heavyweight crown. The 800-227-9759 siles to combat the enemy's he- player has the option of using licopter-attack squadrons. Fea- the supplied boxers or creating HACKER: An adventure game tures 3-D graphics, sound ef- his own challenger. -

A Composers Guide to Game Music Pdf Free Download

A COMPOSERS GUIDE TO GAME MUSIC PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Winifred Phillips | 288 pages | 11 Aug 2017 | MIT Press Ltd | 9780262534499 | English | Cambridge, United States A Composers Guide to Game Music PDF Book The challenges unique to game composers are discussed at length. Video Games. Either we turn down the gig or set aside our emotions and listen for some musical element in that genre that tickles our interest. Music in video games is often a sophisticated, complex composition that serves to engage the player, set the pace of play, and aid interactivity. It really is intended for composers. Recommended: Ear Training Games. Each layer needs to have its moments to shine, but not at the expense of the others. Aspiring composers should have a burning desire to contribute their own ideas to the larger musical conversation. Phillips offers detailed coverage of essential topics, including musicianship and composition experience; immersion; musical themes; music and game genres; workflow; working with a development team; linear music; interactive music, both rendered and generative; audio technology, from mixers and preamps to software; and running a business. July 2, He also wangles in some light electronics for many of his compositions, so expect to hear something slightly different every time. This book offers guidance to composers who are interested in writing music for video games. But in a video game the length of each scene or level can vary greatly. Outside of the theories and techniques for creating this music, there is also a wealth of information on how to function within a development team and how to meet the expectations of the job. -

Building a Music Rhythm Video Game Information Systems and Computer

Building a music rhythm video game Ruben Rodrigues Rebelo Thesis to obtain the Master of Science Degree in Information Systems and Computer Engineering Supervisor: Prof. Rui Filipe Fernandes Prada Examination Committee Chairperson: Nuno Joao˜ Neves Mamede Supervisor: Prof. Rui Filipe Fernandes Prada Member of the Committee: Carlos Antonio´ Roque Martinho November 2016 Acknowledgments I would like to thank my supervisor, Prof. Rui Prada for the support and for making believe that my work in this thesis was not only possible, but also making me view that this work was important for myself. Also I want to thank Carla Boura Costa for helping me through this difficult stage and clarify my doubts that I was encountered this year. For the friends that I made this last year. Thank you to Miguel Faria, Tiago Santos, Nuno Xu, Bruno Henriques, Diogo Rato, Joana Condec¸o, Ana Salta, Andre´ Pires and Miguel Pires for being my friends and have the most interesting conversations (and sometimes funny too) that I haven’t heard in years. And a thank you to Vaniaˆ Mendonc¸a for reading my dissertation and suggest improvements. To my first friends that I made when I entered IST-Taguspark, thank you to Elvio´ Abreu, Fabio´ Alves and David Silva for your support. A small thank you to Prof. Lu´ısa Coheur for letting me and my origamis fill some of the space in the room of her students. A special thanks for Inesˆ Fernandes for inspire me to have the idea for the game of the thesis, and for giving special ideas that I wish to implement in a final version of the game. -

Music Games Rock: Rhythm Gaming's Greatest Hits of All Time

“Cementing gaming’s role in music’s evolution, Steinberg has done pop culture a laudable service.” – Nick Catucci, Rolling Stone RHYTHM GAMING’S GREATEST HITS OF ALL TIME By SCOTT STEINBERG Author of Get Rich Playing Games Feat. Martin Mathers and Nadia Oxford Foreword By ALEX RIGOPULOS Co-Creator, Guitar Hero and Rock Band Praise for Music Games Rock “Hits all the right notes—and some you don’t expect. A great account of the music game story so far!” – Mike Snider, Entertainment Reporter, USA Today “An exhaustive compendia. Chocked full of fascinating detail...” – Alex Pham, Technology Reporter, Los Angeles Times “It’ll make you want to celebrate by trashing a gaming unit the way Pete Townshend destroys a guitar.” –Jason Pettigrew, Editor-in-Chief, ALTERNATIVE PRESS “I’ve never seen such a well-collected reference... it serves an important role in letting readers consider all sides of the music and rhythm game debate.” –Masaya Matsuura, Creator, PaRappa the Rapper “A must read for the game-obsessed...” –Jermaine Hall, Editor-in-Chief, VIBE MUSIC GAMES ROCK RHYTHM GAMING’S GREATEST HITS OF ALL TIME SCOTT STEINBERG DEDICATION MUSIC GAMES ROCK: RHYTHM GAMING’S GREATEST HITS OF ALL TIME All Rights Reserved © 2011 by Scott Steinberg “Behind the Music: The Making of Sex ‘N Drugs ‘N Rock ‘N Roll” © 2009 Jon Hare No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means – graphic, electronic or mechanical – including photocopying, recording, taping or by any information storage retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher.