"Local Band Does O.K.": a Case Study of Class and Scene Politics in the Jam Scene of Northwest Ohio

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Umphrey's Mcgee

Umphrey’s McGee Brendan Bayliss: Guitar, vocals Jake Cinninger: Guitar, vocals Joel Cummins: Keyboard, piano, vocals Andy Farag: Percussion Kris Myers: Drums, vocals Ryan Stasik: Bass After 18-plus years of performing more than 100 concerts annually, releasing nine studio albums and selling more than 4.2 million tracks online, Umphrey’s McGee might be forgiven if they chose to rest on their laurels. But then that wouldn’t be consistent with the work ethic demonstrated by the band, which consistently attempts to raise the bar, setting and achieving new goals since forming on the Notre Dame campus in South Bend, Indiana, in 1997. After releasing their eighth studio album, Similar Skin, the first for their own indie label, Nothing Too Fancy (N2F) Music (distributed by RED), the group continued to push the envelope and test the limits. The London Session, was a dream come true for the members having been recorded at the legendary Studio Two at historic Abbey Road. The stealth recording session yielded 10 tracks in a single day, proving once again, the prolific UM waits for no one. As a follow up to The London Session, the envelope pushing continues with the November 11th release of ZONKEY. Umphrey’s McGee has been arranging and performing original mashups live for over eight years. It was only a matter of when, not if, some of those innovative concoctions would find their way into a studio. An album of 12 unique mashups, conceived and arranged by the band, ZONKEY is as seamless as it bizarre, playful as it is razor sharp. -

2015 Inventory of Library by Categories Penny Kittle

2015 Inventory of Library by Categories Penny Kittle The World: Asia, India, Africa, The Middle East, South America & The Caribbean, Europe, Canada Asia & India Escape from Camp 14: One Man’s Remarkable Odyssey from North Korea to Freedom in the West by Blaine Harden Behind the Beautiful Forevers: Life, Death, and Hope in a Mumbai Undercity by Katherine Boo Life of Pi by Yann Martel Boxers & Saints by Geneluen Yang American Born Chinese by Gene Luen Yang The Orphan Master’s Son by Adam Johnson A Fine Balance by Rohinton Mistry Jakarta Missing by Jane Kurtz The Buddah in the Attic by Julie Otsuka First They Killed My Father by Loung Ung A Step From Heaven by Anna Inside Out & Back Again by Thanhha Lai Slumdog Millionaire by Vikas Swarup The Namesake by Jhumpa Lahiri Unaccustomed Earth by Jhumpa Lahiri The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang Girl in Translation by Jean Kwok The Joy Luck Club by Amy Tan The Reason I Jump by Naoki Higashida Nothing to Envy: Ordinary Lives in North Korea by Barbara Demick Q & A by Vikas Swarup Never Fall Down by Patricia McCormick A Moment Comes by Jennifer Bradbury Wave by Sonali Deraniyagala White Tiger by Aravind Adiga Africa What is the What by Dave Eggers They Poured Fire on Us From the Sky by Deng, Deng & Ajak Memoirs of a Boy Soldier by Ishmael Beah Radiance of Tomorrow by Ishmael Beah Running the Rift by Naomi Benaron Say You’re One of Them by Uwem Akpan Cutting for Stone by Abraham Verghese Desert Flower: The Extraordinary Journey of a Desert Nomad by Waris Dirie The Milk of Birds by Sylvia Whitman The -

Grateful Dead Records: Realia

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8k64ggf No online items Guide to the Grateful Dead Records: Realia Wyatt Young, Maureen Carey University of California, Santa Cruz 2012 1156 High Street Santa Cruz 95064 [email protected] URL: http://guides.library.ucsc.edu/speccoll Note Finding aid updated in 2018, 2020, 2021 Guide to the Grateful Dead MS.332.Ser.10 1 Records: Realia Contributing Institution: University of California, Santa Cruz Title: Grateful Dead Records: Realia Creator: Grateful Dead Productions Identifier/Call Number: MS.332.Ser.10 Physical Description: 178 Linear Feet128 boxes, 21 oversize items Date (inclusive): 1966-2012 Stored in Special Collections and Archives. Language of Material: English Access Restrictions Collection open for research. Advance notice is required for access. Use Restrictions Property rights for this collection reside with the University of California. Literary rights, including copyright, are retained by the creators and their heirs. The publication or use of any work protected by copyright beyond that allowed by fair use for research or educational purposes requires written permission from the copyright owner. Responsibility for obtaining permissions, and for any use rests exclusively with the user. Preferred Citation Grateful Dead Records: Realia. MS 332 Ser. 10. Special Collections and Archives, University Library, University of California, Santa Cruz. Acquisition Information Gift of Grateful Dead Productions, 2008. Accurals The first accrual was received in 2008. Second accrual was received in June 2012. Biography The Grateful Dead were an American rock band that formed in 1965 in Northern California. They came to fame as part of author Ken Kesey's Acid Tests, a series of multimedia happenings centered around then-legal LSD. -

The String Cheese Incident the String Cheese Incident

07 . 05 19 . 07.19.05 ROCHESTER, NY . 19 05 . 07 DISC ONE 0 1 INTRO 1:26 02 JUST LIKE TOM THUMB’S BLUES 5:23 03 MLT 15:51 04 RAINBOW SERPENT 6:08 THE STRING CHEESE INCIDENT 05 RESTLESS WIND 10:12 06 TIME GOES BY 4:57 07 BORN ON THE WRONG PLANET 13:24 DISC TWO 0 1 DON’T SAY> 11:45 02 BIRDLAND> 3:05 03 FLYING EAST JAM> 4:24 04 REMINGTON RIDE> 2:22 05 FLYING EAST JAM> 2:48 06 BIRDLAND 3:23 ENCORE 07 CHATTER 1:44 08 BEND DOWN LOW*> 4:03 09 PASS THE DUTCHIE*> 3:50 10 BEND DOWN LOW*> 1:22 1 1 WILL THE CIRCLE BE UNBROKEN* 9:04 THE STRING CHEESE INCIDENT * features Keller Williams on guitar and vocals, Roberto Quintana on percussion (from Spearhead), Brendan Bayliss and Jake Cinninger on FOR ALL PUBLISHING INFO PLEASE VISIT WWW.SCIONTHEROAD.COM/PUBLISH guitar, Joel Cummins on keyboards, Kris Myers on drums (all from Umphrey's McGee) ROCHESTER, NY çπ2005 SCI Fidelity Records. 4760 Walnut St. Suite 106 Boulder, CO 80301 All rights reserved. Unauthorized reproduction is a violation of applicable laws. WWW.STRINGCHEESEINCIDENT.COM WWW.LIVECHEESE.COM ROCHESTER, NY 07 . 05 19 . 07.19.05 ROCHESTER, NY . 19 05 . 07 DISC ONE 0 1 INTRO 1:26 02 JUST LIKE TOM THUMB’S BLUES 5:23 03 MLT 15:51 04 RAINBOW SERPENT 6:08 THE STRING CHEESE INCIDENT 05 RESTLESS WIND 10:12 06 TIME GOES BY 4:57 07 BORN ON THE WRONG PLANET 13:24 DISC TWO 0 1 DON’T SAY> 11:45 02 BIRDLAND> 3:05 03 FLYING EAST JAM> 4:24 04 REMINGTON RIDE> 2:22 05 FLYING EAST JAM> 2:48 06 BIRDLAND 3:23 ENCORE 07 CHATTER 1:44 08 BEND DOWN LOW*> 4:03 09 PASS THE DUTCHIE*> 3:50 10 BEND DOWN LOW*> 1:22 1 1 WILL THE CIRCLE BE UNBROKEN* 9:04 THE STRING CHEESE INCIDENT * features Keller Williams on guitar and vocals, Roberto Quintana on percussion (from Spearhead), Brendan Bayliss and Jake Cinninger on FOR ALL PUBLISHING INFO PLEASE VISIT WWW.SCIONTHEROAD.COM/PUBLISH guitar, Joel Cummins on keyboards, Kris Myers on drums (all from Umphrey's McGee) ROCHESTER, NY çπ2005 SCI Fidelity Records. -

September 1995

Features CARL ALLEN Supreme sideman? Prolific producer? Marketing maven? Whether backing greats like Freddie Hubbard and Jackie McLean with unstoppable imagination, or writing, performing, and producing his own eclectic music, or tackling the business side of music, Carl Allen refuses to be tied down. • Ken Micallef JON "FISH" FISHMAN Getting a handle on the slippery style of Phish may be an exercise in futility, but that hasn't kept millions of fans across the country from being hooked. Drummer Jon Fishman navigates the band's unpre- dictable musical waters by blending ancient drum- ming wisdom with unique and personal exercises. • William F. Miller ALVINO BENNETT Have groove, will travel...a lot. LTD, Kenny Loggins, Stevie Wonder, Chaka Khan, Sheena Easton, Bryan Ferry—these are but a few of the artists who have gladly exploited Alvino Bennett's rock-solid feel. • Robyn Flans LOSING YOUR GIG AND BOUNCING BACK We drummers generally avoid the topic of being fired, but maybe hiding from the ax conceals its potentially positive aspects. Discover how the former drummers of Pearl Jam, Slayer, Counting Crows, and others transcended the pain and found freedom in a pink slip. • Matt Peiken Volume 19, Number 8 Cover photo by Ebet Roberts Columns EDUCATION NEWS EQUIPMENT 100 ROCK 'N' 10 UPDATE 24 NEW AND JAZZ CLINIC Terry Bozzio, the Captain NOTABLE Rhythmic Transposition & Tenille's Kevin Winard, BY PAUL DELONG Bob Gatzen, Krupa tribute 30 PRODUCT drummer Jack Platt, CLOSE-UP plus News 102 LATIN Starclassic Drumkit SYMPOSIUM 144 INDUSTRY BY RICK -

James Edwin Pope

James Edwin Pope EXPERIENCE ─────────────────────────────────────────────────── Toyota (Demo) Husband (Lead) Commercial 2019 Amtrak Traveler (Lead) Commercial 2019 The Greatest Sketch Show in America Actor (Various Roles) Theatre 2019 Centra Health Father (Lead) Commercial 2019 Maryland Pride Be Like Director/Writer/Actor Film (Short) 2019 United Airlines Husband (Lead) Commercial 2018 Canon, Inc. Father (Lead) Commercial 2018 Moxy by Marriott Hotels Interior Designer (Lead) Commercial 2018 Maryland Live! Casino Casino Patron (Lead) Print 2018 Black and Decker Homeowner (Lead) Print 2018 Giant Foods Party-Goer (Lead) Commercial 2018 Thompson Creek Windows Homeowner (Lead) Commercial 2018 Dark City: Beneath the Beat Police Officer/Dancer Film 2018 New Year’s Daze Director/Writer/Actor (Lead) Film (Short) 2017 Epic Office XMas Party Director/Choreographer Film (Short) 2017 Microtel by Wyndham Hotels Father (Lead) Print 2017 Time Machine Dancer/Writer Theatre 2017 Tinder On-Demand Director/Writer/Actor Film (Short) 2017 The Motion Challenge Director/Choreographer Film (Short) 2017 Political Dance Battle Director/Writer/Actor Film (Short) 2016 Cards Against Humanity IRL (Web Series) Director/Writer/Actor Film (Short) 2016 Heroes and Villains Dancer Theatre 2016 New Year (Parody) Director/Writer Film (Short) 2016 Steve Harvey Show Guest Television 2016 The Today Show Guest Television 2015 Countertop Solutions Director/Writer/Actor (Lead) Commercial 2015 WORK EXPERIENCE ──────────────────────────────────────────────────── Krewski, LLC Founder -

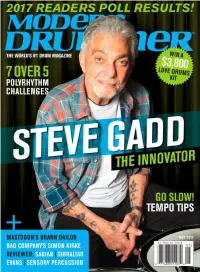

40 Steve Gadd Master: the Urgency of Now

DRIVE Machined Chain Drive + Machined Direct Drive Pedals The drive to engineer the optimal drive system. mfg Geometry, fulcrum and motion become one. Direct Drive or Chain Drive, always The Drummer’s Choice®. U.S.A. www.DWDRUMS.COM/hardware/dwmfg/ 12 ©2017Modern DRUM Drummer WORKSHOP, June INC. ALL2014 RIGHTS RESERVED. ROLAND HYBRID EXPERIENCE RT-30H TM-2 Single Trigger Trigger Module BT-1 Bar Trigger RT-30HR Dual Trigger RT-30K Learn more at: Kick Trigger www.RolandUS.com/Hybrid EXPERIENCE HYBRID DRUMMING AT THESE LOCATIONS BANANAS AT LARGE RUPP’S DRUMS WASHINGTON MUSIC CENTER SAM ASH CARLE PLACE CYMBAL FUSION 1504 4th St., San Rafael, CA 2045 S. Holly St., Denver, CO 11151 Veirs Mill Rd., Wheaton, MD 385 Old Country Rd., Carle Place, NY 5829 W. Sam Houston Pkwy. N. BENTLEY’S DRUM SHOP GUITAR CENTER HALLENDALE THE DRUM SHOP COLUMBUS PRO PERCUSSION #401, Houston, TX 4477 N. Blackstone Ave., Fresno, CA 1101 W. Hallandale Beach Blvd., 965 Forest Ave., Portland, ME 5052 N. High St., Columbus, OH MURPHY’S MUSIC GELB MUSIC Hallandale, FL ALTO MUSIC RHYTHM TRADERS 940 W. Airport Fwy., Irving, TX 722 El Camino Real, Redwood City, CA VIC’S DRUM SHOP 1676 Route 9, Wappingers Falls, NY 3904 N.E. Martin Luther King Jr. SALT CITY DRUMS GUITAR CENTER SAN DIEGO 345 N. Loomis St. Chicago, IL GUITAR CENTER UNION SQUARE Blvd., Portland, OR 5967 S. State St., Salt Lake City, UT 8825 Murray Dr., La Mesa, CA SWEETWATER 25 W. 14th St., Manhattan, NY DALE’S DRUM SHOP ADVANCE MUSIC CENTER SAM ASH HOLLYWOOD DRUM SHOP 5501 U.S. -

John Zorn Artax David Cross Gourds + More J Discorder

John zorn artax david cross gourds + more J DiSCORDER Arrax by Natalie Vermeer p. 13 David Cross by Chris Eng p. 14 Gourds by Val Cormier p.l 5 John Zorn by Nou Dadoun p. 16 Hip Hop Migration by Shawn Condon p. 19 Parallela Tuesdays by Steve DiPo p.20 Colin the Mole by Tobias V p.21 Music Sucks p& Over My Shoulder p.7 Riff Raff p.8 RadioFree Press p.9 Road Worn and Weary p.9 Bucking Fullshit p.10 Panarticon p.10 Under Review p^2 Real Live Action p24 Charts pJ27 On the Dial p.28 Kickaround p.29 Datebook p!30 Yeah, it's pink. Pink and blue.You got a problem with that? Andrea Nunes made it and she drew it all pretty, so if you have a problem with that then you just come on over and we'll show you some more of her artwork until you agree that it kicks ass, sucka. © "DiSCORDER" 2002 by the Student Radio Society of the Un versify of British Columbia. All rights reserved. Circulation 17,500. Subscriptions, payable in advance to Canadian residents are $15 for one year, to residents of the USA are $15 US; $24 CDN ilsewhere. Single copies are $2 (to cover postage, of course). Please make cheques or money ordei payable to DiSCORDER Magazine, DEADLINES: Copy deadline for the December issue is Noven ber 13th. Ad space is available until November 27th and can be booked by calling Steve at 604.822 3017 ext. 3. Our rates are available upon request. -

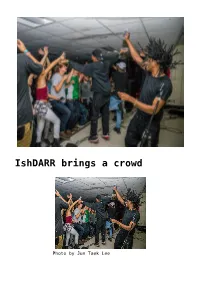

Ishdarr Brings a Crowd,Iowa Band Speaks on Locality,Field Report To

IshDARR brings a crowd Photo by Jun Taek Lee A packed crowd gathered in Gardner on Friday, Nov. 6, to hear from three young hip-hop artists—Young Eddy, Kweku Collins and IshDARR (pictured to the left). IshDARR is based out of Milwaukee, Wis. The sharp-tongued 19- year-old released a critically acclaimed album, “Old Soul, Young Spirit,” earlier this year. He largely pulled material from that album during the performance. The youthful, ecstatic energy of his recorded material transferred seamlessly to the stage. IshDARR was totally engaging for the duration of the set and did not shy away from talking with the audience, eliciting laughter and cheers. It wasn’t a terribly long set, but one that kept the people in attendance rapt from start to finish. Milwaukee is an exciting place to be an MC in 2015. The Midwestern city has recently cultivated a vibrant and dynamic DIY hip hop scene that’s only getting larger. IshDaRR, one of the youngest and most prominent members of the scene, proved on Friday night that he’s got a lot to share with the world. Assuredly, he is only getting started. Friday night was the third time that Young Eddy, aka Greg Margida ’16, has performed on campus and he is sure to have more performances next semester. Kweku Collins hails from Evanston, Ill., and this was his first time performing in Grinnell. Iowa band speaks on locality The S&B’s Concerts Correspondent Halley Freger ‘17 sat down with Pelvis’ guitarist and vocalist, Nao Demand, before his Gardner set on Friday, Oct. -

Karizma Biog He's One of the Most In-Demand Djs on the Worldwide

Karizma biog He’s one of the most in-demand DJs on the worldwide house circuit, his productions are a must-check for any self-respecting house lover, and his remix talents are sought out by some of the biggest names in the music business. Truly Karizma is a man at the very peak of his game. But then he’s been doing this for a while. Born in Baltimore, Maryland in 1970, Chris Clayton became fascinated by music from an early age. “My grandma used to go to flea markets and come back with all these records, and I was just OBSESSED with them!” he recalls, laughing. “This was when I was about five years old. I’d sit listening to all these records for hours on end, and while I was listening I’d be studying the liner notes and the sleeves. By the time I was seven, you could pick up any record in our house and I could tell you who played on it, who produced it and using what equipment!” It was only natural that a desire to get involved with music would follow, and young Chris spent his teens learning to DJ – at that time playing hip-hop and the nascent ‘Baltimore club music’, a sub-genre that’s today similar in style to Detroit ghetto tech/Miami bass but which in its early days drew much inspiration from the go-go music coming out of nearby Philadelphia – and playing in a succession of bands. By the age of 19, he was playing with his first “proper” band, a Baltimore club music outfit called Unruly. -

By Erik Jensen

UpstateLIVE July / August 2008 : Issue #2 Herby One : editor/ad rep Music Guide Erik Jensen : senior writer Jennifer Hofstra : photography Welcome to the UpstateLIVE Music Guide. It was created to help promote LIVE www.UpstateLIVE.net MUSIC and MUSICIANS in Upstate New www.myspace.com/upstatelivenet York. It gives fans a chance to see what is happening in different regions of the state, Upcoming issues and gives industry insiders some much Issue #3 : SEPT-OCT (*Aug 22) needed networking. Issue #4 : NOV-DEC (*Oct 24) *Deadline It is distributed to live music bars and ------------------------------------------------------------- theatres, music stores and shops, cafes and UpstateLIVE Music Guide restaurants, and circulated by staff, street is published by team members, bands and fans at concerts GOLDSTAR Entertainment and festivals throughout the Upstate New PO Box 565 - Baldwinsville, NY 13027 York Region. The goal of UpstateLIVE is to create a statewide Live Music Community, joining each of the state’s local music scenes into one regional network. We are on our way! UpstateLIVE’s main objective is to showcase all of the outstanding local, regional, and national bands playing Upstate New York. Festivals, concerts, music venues, music shops and sponsors are also highlighted. UpstateLIVE is published 6 times per year (every 2 months), and is an everlasting archive of the great music we share in Upstate NY. For more information visit us on the internet at www.upstatelive.net and at myspace.com/upstatelivenet. Feel free to contact us at [email protected] Hello Friends! Erik Jensen here. I have written a ton PORTISHEAD - “THIRD” of stuff about Upstate area bands, venues and events Straight up darkness. -

The Grateful Dead and the Long 1960S – Syllabus Department of Music, University of California – Santa Cruz, Spring Quarter 2018

Music 80N: The Grateful Dead and the Long 1960s – Syllabus Department of Music, University of California – Santa Cruz, Spring Quarter 2018 Instructor: Dr. Melvin Backstrom [email protected] Teaching Assistants: Marguerite Brown [email protected] Ike Minton [email protected] Class Schedule: MWF, 12pm-1:05pm, Music 101 (Recital Hall) OFFICE HOURS & LOCATION INSTRUCTOR Room 126 Mondays 2-3pm or by appointment TEACHING ASSISTANTS TBA Course Description This music history survey course uses the seminal Bay Area rock band/improvisational ensemble the Grateful Dead as a lens to understand the music and broader history of countercultural music from the 1950s to the present. It combines an extensive engagement with the music of the Grateful Dead, as well as other related musicians, along with a wide variety of readings from non- musical history, political science, philosophy and cultural studies in order to encourage a deep reflection on what the countercultures of the 1960s meant in their heyday, and what their descendants continue to mean today in both musical and non-musical realms. It aims to be both an introduction to those interested in the Grateful Dead, though largely born after the group’s disbandment in 1995, as well as to appeal to those with a broader interest in recent cultural history. Because the University of California – Santa Cruz is the home of the Grateful Dead Archive, students are encouraged to make use of it. However, given the number of students in the course and limitations of UCSC Special Collections its use will not be required. Readings All texts will be available through UCSC’s online system.