Competition and Public Service Broadcasting: Stimulating Creativity Or Servicing Capital?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IRONBIRD AERIAL CINEMATOGRAPHY LTD AERIAL FILMING CV ACCREDITATIONS • CAA Permission for Commercial Operations (PFCO) Holders

IRONBIRD AERIAL CINEMATOGRAPHY LTD 16 Jordan St Studio D Liverpool, L10BP Tel: 0151 909 8464 Mail: [email protected] iron-bird.co.uk AERIAL FILMING CV ACCREDITATIONS • CAA Permission for Commercial Operations (PFCO) holders. First issued 2013, current OSC PFCO valid until 1st AUGUST 2020 - valid for UAS (unmanned aircraft systems) up to 20kg. • Holders of enhanced Operational Safety Case Permissions (heavy lifts within Towns and Cities) • Euro-USC BNUC-s & RPQ qualified Pilots. Feature & Independant Film • (2019) ’83’ Phantom Films • (2017) ‘Tolkien’ Fox Searchlight UK • (2017) ‘Stan and Ollie’ BBC Film // Bowler Hat • (2017) ‘Farming’ HH Films // Farming The Film LTD • (2016) ‘Eaten By Lions’ Mecca Films • (2013) ‘Mrs Browns Boys Da’ Movie’ - Penalty Kick Films // BBC Films // Thats Nice Broadcast & Drama • (2019) ‘Hanna II’ UMSI Productions Ltd • (2019) ‘Tin Star’ Season 3 Kudos • (2019) ‘Cobra’ New Pictures // All3 Media • (2019) ‘The English Game’ Netflix • (2019) ‘The Stranger’ Red Productions • (2019) ‘Years & Years’ Red Productions • (2019) ‘Bancroft II’ ITV • (2018) ‘Deep Water’ Kudos // ITV • (2018) ‘Long Shot - Catfish and the Bottle Men’ Island Records // VEVO • (2018) ‘Hospital’ LabelTV // BBC • (2018) ‘Silent Witness 22’ BBC • (2018) ‘The Feed’ Studio Lambert // Amazon Prime • (2018) ‘Creeped Out 2’ DHX Media // CBBC • (2018) ‘Care’ LA Productions // BBC One • (2018) ‘Wander Lust’ Red Productions // Netflix • (2018) ‘All or Nothing MCFC’ Amazon Prime • (2018) ‘Free Rein’ Lime Pictures // Netflix • (2017) ‘Bulletproof’ Vertigo -

Drama Drama Documentary

1 Springvale Terrace, W14 0AE Graeme Hayes 37-38 Newman Street, W1T 1QA SENIOR COLOURIST 44-48 Bloomsbury Street WC1B 3QJ Tel: 0207 605 1700 [email protected] Drama The People Next Door 1 x 60’ Raw TV for Channel 4 Enge UKIP the First 100 Days 1 x 60’ Raw TV for Channel 4 COLOURIST Cyberbully 1 x 76’ Raw TV for Channel 4 BAFTA & RTS Nominations Playhouse Presents: Foxtrot 1 x 30’ Sprout Pictures for Sky Arts American Blackout 1 x 90’ Raw TV for NGC US Blackout 1 x 90’ Raw TV for Channel 4 Inspector Morse 6 x 120’ ITV Studios for ITV 3 Poirot’s Christmas 1 x 100’ ITV Studios for ITV 3 The Railway Children 1 x 100’ ITV Studios for ITV 3 Taking the Flak 6 x 60’ BBC Drama for BBC Two My Life as a Popat 14 x 30’ Feelgood Fiction for ITV 1 Suburban Shootout 4 x & 60’ Feelgood Fiction for Channel 5 Slap – Comedy Lab 8 x 30’ World’s End for Channel 4 The Worst Journey in the World 1 x 60’ Tiger Aspect for BBC Four In Deep – Series 3 4 x 60’ Valentine Productions for BBC1 Drama Documentary Nazi Megaweapons Series III 1 x 60’ Darlow Smithson for NGCi Metropolis 1 x 60’ Nutopia for Travel Channel Million Dollar Idea 2 x 60’ Nutopia Hostages 1 x 60’ Al Jazeera Cellblock Sisterhood 3 x 60’ Raw TV Planes That Changed the World 3 x 60’ Arrow Media Nazi Megaweapons Series II 1 x 60’ Darlow Smithson for NGCi Dangerous Persuasions Series II 6 x 60’ Raw TV Love The Way You Lie 6 x 60’ Raw TV Mafia Rules 1 x 60’ Nerd Nazi Megaweapons 5 x 60’ Darlow Smithson for NGCi Breakout Series 2 10 x 60’ Raw TV for NGC Paranormal Witness Series 2 12 x 60’ Raw TV -

Bearded Tit: a Love Story with Feathers

TO BE PROOFREAD Title: The Bearded Tit: A love story with feathers Author: Rory McGrath Year: 2008 Synopsis: ‘The Bearded Tit’ is Rory McGrath’s story of life among birds—from a Cornish boyhood wandering gorse-tipped cliffs listening to the song of the yellowhammer with his imaginary girlfriend, or drawing gravity-defying jackdaws in class when he should have been applying himself to physics, to quoting the Latin names of birds to give himself a fighting chance of a future with JJ—the most beautiful girl he had ever seen. As an adult, or what passes for one, Rory recounts becoming a card-carrying birdwatcher, observing his first skylark—peerless king of the summer sky —while stoned; his repeatedly failed attempts to get up at the crack of dawn like the real twitchers; and his flawed bid to educate his utterly unreconstructed drinking mate Danny in the ways of birding. Rory’s tale is a thoroughly educational, occasionally lyrical and highly amusing romp through the hidden byways of birdwatching and, more importantly, a love story you’ll never forget. A message to my readers Many thanks to both of you. Another message to my readers There is nothing quite like the sentence ‘And this is a true story’ to make you instantly doubt all that you are about to hear. And ‘This is no word of a lie’ invariably precedes a tale of palpable mendacity. ‘I kid you not, hand on heart’, you just know heralds a pile of arrant bullshit. With all this foremost in my mind, I nervously say to you now that what follows is a true story. -

TV Producer Simon Withington

SIMON WITHINGTON [email protected] / www.simonwithington.co.uk BIOGRAPHY I am an award-winning freelance television producer, having produced many high-profile shows with big-name talent. Recently, I have produced multiple 3-hour archive shows for Channel 5 (When… Goes Horribly Wrong) where I’ve overseen up to 7 edits and managing a team of around 25 people. I originated Greatest Celebrity Wind Ups Ever! with Joe Pasquale which consistently rated 25% above slot average for Channel 5 and World Cup Epic Fails hosted by Angus Deayton for ITV in 2014. which rated with 3.7 million viewers and resulted in a subsequent commission, Christmas Epic Fails. Often working with top talent and priding myself on always coming in on budget, my television background has covered both shiny floor Entertainment & Factual Entertainment programming. I also self-shoot and edit. EMPLOYMENT HISTORY SHOWRUNNER / EXECUTIVE PRODUCER: CRACKIT PRODUCTIONS (Executive Producers: Elaine Hackett & Jason Wells) (November ’16 to Dec ‘18) When…Goes Horribly Wrong. (14 x 180 mins) Live TV, Celebrity, Chatshows, Gameshows, Kids TV, Talent Shows, Reality TV, Television 2, Comedy, Award Shows, News, Eurovision, Christmas, TV Animals (September ’17 to Jan ‘18) Greatest Celebrity Wind-ups Ever! Series (6 x 60 mins) (June ’17 to July ‘17) Greatest Celebrity Wind-ups Ever! (1 x 60 mins) (May ’18) 5 Goes to Eurovision: Greatest Hits (1 x 60 mins) * Overseeing top-rating fast-turnaround talking heads clip-shows for Channel 5. Multiple edits, up to 25 staff * Directing talking heads. Clearing archive within tight budgets. Clearing and re-versioning for International market * Greatest Celebrity Wind-Ups Ever went from commission to on-air in just 3 weeks. -

Venustheatre

VENUSTHEATRE Dear Member of the Press: Thank you so much for coverage of The Speed Twins by Maureen Chadwick. I wanted to cast two women who were over 60 to play Ollie and Queenie. And, I'm so glad I was able to do that. This year, it's been really important for me to embrace comedy as much as possible. I feel like we all probably need to laugh in this crazy political climate. Because I thought we were losing this space I thought that this show may be the last for me and for Venus. It turns out the new landlord has invited us to stay and so, the future for Venus is looking bright. There are stacks of plays waiting to be read and I look forward to spending the summer planning the rest of the year here at Venus. This play is a homage, in some ways, to The Killing of Sister George. I found that script in the mid-nineties when it was already over 30 years old and I remember exploring it and being transformed by the archetypes of female characters. To now be producing Maureen's play is quite an honor. She was there! She was at the Gateway. She is such an impressive writer and this whole experience has been very dierent for Venus, and incredibly rewarding. I hope you enjoy the show. All Best, Deborah Randall Venus Theatre *********************************************** ABOUT THE PLAYWRIGHT PERFORMANCES: receives about 200 play submissions and chooses four to produce in the calendar year ahead. Each VENUSTHEATRE Maureen Chadwick is the creator and writer of a wide range of award-winning, critically acclaimed and May 3 - 27, 2018 production gets 20 performances. -

Page 1 of 3 Steven Cass. Senior Floor Manager. Contact: Www

Steven Cass. Senior Floor Manager. Contact: www.stevencass.co.uk About Senior television and event Floor Manager with over 15 years experience in the industry. Working across television shows and corporate events, many live, as both a Senior Floor Manager and 1st Assistant Director. Productions managed range from light entertainment and children’s shows through to sport, factual and corporate. Education BEng (Hons) 2:1 Electronics and Computing – Nottingham Trent University Training BBC Safe Management of Productions – part 1 BBC Safe Management of Productions – part 2 1 year placement, BBC TV Centre – BBC Special Projects Shows Entertainment The X Factor – Arena Auditions Talkback, ITV 1 The Royal Variety Performance ITV, ITV 1 Piers Morgan’s Life Stories ITV, ITV 1 Ant n’ Dec Sat Takeaway – Locations (Live) Granada, ITV 1 Most Haunted – UK, USA, Romania (Live) Antix Productions, Living TV National Lottery (Live) Endemol, BBC 1 John Bishop’s Only Joking Channel X, Sky 1 Let’s Do Lunch With Gino & Mel (Live) ITV, ITV 1 Big Brother (Live) Endemol, Channel 5 V Graham Norton So Television, Channel 4 The Only Way Is Essex (Scripted Reality) Lime Pictures, ITV Be Britain’s Next Top Model Thumbs Up, Living Children In Need – Stage (Live) BBC, BBC 1 Loose Women (Live) ITV, ITV 1 This Morning (Live) ITV, ITV 1 Album Chart Show 3DD Productions, Channel 4 Eggheads (Quiz) 12 Yard, BBC 1 Saturday Cookbook Optimum, ITV 1 Dancing On Ice: Defrosted (Live) Granada, ITV 2 I’m A Celeb Get Me Out – Jungle Drums (Live) Granada, ITV 2 Page 1 of 3 The Price -

Competition and Public Service Broadcasting: Stimulating Creativity Or Servicing Capital?

COMPETITION AND PUBLIC SERVICE BROADCASTING: STIMULATING CREATIVITY OR SERVICING CAPITAL? Centre for Business Research, University of Cambridge Working paper No. 408 by Simon Turner Department of Health Services Research and Policy, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, Keppel Street, London, WC1E 7HT Email: [email protected] Ana Lourenço School of Economics and Management, Catholic University of Portugal, Rua Diogo Botelho, 1327, 4169-005, Porto, Portugal. Email: [email protected] June 2010 This working paper forms part of the CBR Research Programme on Corporate Governance Abstract In UK public service broadcasting, recent regulatory change has increased the role of the private sector in television production, culminating in the BBC’s recent introduction of ‘creative competition’ between in-house and independent television producers. Using the concept of ‘cognitive distance’, this paper focuses on the increasing role of the independent sector as a source of creativity and innovation in the delivery of programming for the BBC. The paper shows that the intended benefits of introducing new competencies into public service broadcasting have been thwarted by, on the one hand, a high level of cognitive proximity between in-house and external producers and, on the other, a conflict in values between the BBC and the independent sector, with the latter responding to a commercial imperative that encourages creativity in profitable genres, leaving gaps in other areas of provision. While recent regulatory reform appears to have had a limited impact on the diversity of programming, it does suggest a closer alignment of programme content with the imperatives of capital. Implications for the literature on communities of practice are noted. -

Daran Little

DARAN LITTLE Daran is an experienced BAFTA and RTS award-winning and EMMY-nominated TV drama writer. His credits include CORONATION STREET (on which he was one of the core writers for many years and won a 2010 Writers’ Guild Award), EASTENDERS and HOLLYOAKS. He was the Associate Head Writer on the US soap ALL MY CHILDREN for ABC, for which he was nominated for an EMMY award. Daran’s original drama THE ROAD TO CORONATION STREET was the winner of the 2011 BAFTA and RTS awards for Best Single Drama, the Broadcast Digital Award for Best Scripted Programme and the 2011 RTS North West award for Best Script Writer. Telling the story of CORONATION STREET it was directed by Charles Sturridge and starred Jane Horrocks, Celia Imrie and Stephen Berkoff amongst others. Daran is currently developing new drama series ideas with Atticus Film & Television, and has recently worked on new development projects with Hat Trick Productions and Vox Pictures, in addition to writing on EASTENDERS as part of the core team. He has recently worked on several new ideas with a number of producers, including ideas in development with ITV, BBC Comedy, Buccaneer Media and Monkey Kingdom. NBC Universal commissioned him to write a series bible and pilot script for a drama series and he co-wrote two pilot scripts for a new drama idea with Rupert Everett for Scott Free Productions. Daran has also worked with Lovely Day Productions, developing a number of original drama and comedy drama ideas including a comedy pilot, KITTEN CHIC, which premiered on Sky Living as part of their Love Matters season in April 2013. -

Queer Television Thesis FINAL DRAFT Amended Date and Footnotes

Queer British Television: Policy and Practice, 1997-2007 Natalie Edwards PhD thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham School of American and Canadian Studies, January 2010 Abstract Representations of gay, lesbian, queer and other non-heterosexualities on British terrestrial television have increased exponentially since the mid 1990s. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer characters now routinely populate mainstream series, while programmes like Queer as Folk (1999-2000), Tipping the Velvet (2002), Torchwood (2006-) and Bad Girls (1999-2006) have foregrounded specifically gay and lesbian themes. This increase correlates to a number of gay-friendly changes in UK social policy pertaining to sexual behaviour and identity, changes precipitated by the election of Tony Blair’s Labour government in 1997. Focusing primarily on the decade following Blair’s installation as Prime Minister, this project examines a variety of gay, lesbian and queer-themed British television programmes in the context of their political, cultural and industrial determinants, with the goal of bridging the gap between the cultural product and the institutional factors which precipitated its creation. Ultimately, it aims to establish how and why this increase in LGBT and queer programming occurred when it did by relating it to the broader, government-sanctioned integration of gays, lesbians and queers into the imagined cultural mainstream of the UK. Unlike previous studies of lesbian, gay and queer film and television, which have tended to draw conclusions about cultural trends purely through textual analysis, this project uses government and broadcasting industry policy documents as well as detailed examination of specific television programmes to substantiate links between the cultural product and the wider world. -

“Bad Girls Changed My Life”: Homonormativity in a Women's

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Herman, Didi (2003) ”Bad Girls Changed My Life”: Homonormativity in a Women’s Prison Drama. Critical Studies in Media Communication, 20 (2). pp. 141-159. ISSN 1529-5036. DOI https://doi.org/10.1080/07393180302779 Link to record in KAR https://kar.kent.ac.uk/1570/ Document Version UNSPECIFIED Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html Kent Academic Repository – http://kar.kent.ac.uk “Bad Girls Changed My Life”: Homonormativity in a Women’s Prison Drama Didi Herman â Critical Studies in Media Communication 20 (2) pp 141 – 159 2003 Not Published Version Abstract: This paper explores representations of sexuality in a popular British television drama. The author argues that the program in question, Bad Girls, a drama set in a women’s prison, conveys a set of values that are homonormative. -

Codes Used in D&M

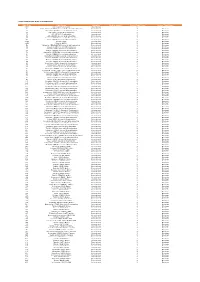

CODES USED IN D&M - MCPS A DISTRIBUTIONS D&M Code D&M Name Category Further details Source Type Code Source Type Name Z98 UK/Ireland Commercial International 2 20 South African (SAMRO) General & Broadcasting (TV only) International 3 Overseas 21 Australian (APRA) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 36 USA (BMI) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 38 USA (SESAC) Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 39 USA (ASCAP) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 47 Japanese (JASRAC) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 48 Israeli (ACUM) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 048M Norway (NCB) International 3 Overseas 049M Algeria (ONDA) International 3 Overseas 58 Bulgarian (MUSICAUTOR) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 62 Russian (RAO) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 74 Austrian (AKM) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 75 Belgian (SABAM) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 79 Hungarian (ARTISJUS) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 80 Danish (KODA) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 81 Netherlands (BUMA) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 83 Finnish (TEOSTO) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 84 French (SACEM) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 85 German (GEMA) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 86 Hong Kong (CASH) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 87 Italian (SIAE) General & Broadcasting International 3 Overseas 88 Mexican (SACM) General & Broadcasting -

Club Victim's Hallucinations After Assault

ATTACKER GAVE Q , Grants to go after ME DRUGS KISS’“election Club victim’s By MATTHEW QENEVER FUTURE generations of students face having to cope without any financial support from the government hallucinations whoever wins the general election. The high-powered Dealing Committee, backed by both Labour and the Conservative after assault party, is set to recommend the phasing out of the student By LAURA DAVIS grant as soon as next summer. Tony Blair has said he is A TERRIFIED clubber committed to scrapping the student grant system and collapsed alter a man grabbed replacing it with a series of loans to be paid back over a her for a french kiss and forced 20-year period. And a source on the committee admitted: two LSD tablets down her throat. “Nobody is defending the The student was celebrating the end of maintenance grant You have to find ways of cutting costs in term in Majestyk when the stranger the system.” seized her and pushed the drugs into her mouth with his tongue. Leeds North-West: During the next 12 hours she suffered turn to pages 16-17 horrific hallucinations, believing she was being Simon Cafftey, President of attacked by six foot spiders. LMUSU, sits on the A friend who stayed with the student, who does not committee as a member of the wish to be named, throughout the night and said she was governance and structure sub intent on hurting herself: “She kept banging her head group. He said: “Higher against the wall and it didn’t seem to hurt her.” education should be free in The victim confronted the manager of Majestyk two days principle, but the fact is that later, but said although he expressed concern, he was unable to the money just isn’t there at the help.