226928674.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

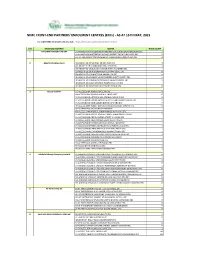

NIMC FRONT-END PARTNERS' ENROLMENT CENTRES (Ercs) - AS at 15TH MAY, 2021

NIMC FRONT-END PARTNERS' ENROLMENT CENTRES (ERCs) - AS AT 15TH MAY, 2021 For other NIMC enrolment centres, visit: https://nimc.gov.ng/nimc-enrolment-centres/ S/N FRONTEND PARTNER CENTER NODE COUNT 1 AA & MM MASTER FLAG ENT LA-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG AGBABIAKA STR ILOGBO EREMI BADAGRY ERC 1 LA-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG AGUMO MARKET OKOAFO BADAGRY ERC 0 OG-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG BAALE COMPOUND KOFEDOTI LGA ERC 0 2 Abuchi Ed.Ogbuju & Co AB-ABUCHI-ED ST MICHAEL RD ABA ABIA ERC 2 AN-ABUCHI-ED BUILDING MATERIAL OGIDI ERC 2 AN-ABUCHI-ED OGBUJU ZIK AVENUE AWKA ANAMBRA ERC 1 EB-ABUCHI-ED ENUGU BABAKALIKI EXP WAY ISIEKE ERC 0 EN-ABUCHI-ED UDUMA TOWN ANINRI LGA ERC 0 IM-ABUCHI-ED MBAKWE SQUARE ISIOKPO IDEATO NORTH ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UGBA AFOR OBOHIA RD AHIAZU MBAISE ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UGBA AMAIFEKE TOWN ORLU LGA ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UMUNEKE NGOR NGOR OKPALA ERC 0 3 Access Bank Plc DT-ACCESS BANK WARRI SAPELE RD ERC 0 EN-ACCESS BANK GARDEN AVENUE ENUGU ERC 0 FC-ACCESS BANK ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA WUSE II ERC 0 FC-ACCESS BANK LADOKE AKINTOLA BOULEVARD GARKI II ABUJA ERC 1 FC-ACCESS BANK MOHAMMED BUHARI WAY CBD ERC 0 IM-ACCESS BANK WAAST AVENUE IKENEGBU LAYOUT OWERRI ERC 0 KD-ACCESS BANK KACHIA RD KADUNA ERC 1 KN-ACCESS BANK MURTALA MOHAMMED WAY KANO ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ACCESS TOWERS PRINCE ALABA ONIRU STR ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ADEOLA ODEKU STREET VI LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA STR VI ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK IKOTUN JUNCTION IKOTUN LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ITIRE LAWANSON RD SURULERE LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK LAGOS ABEOKUTA EXP WAY AGEGE ERC 1 LA-ACCESS -

Rights of Children and Parents in Holy Quran Masumeh Saeidi1, Maryam Ajilian2, Hamid Farhangi3, * Gholam Hasan Khodaei41

http:// ijp.mums.ac.ir Review Article Rights of Children and Parents in Holy Quran Masumeh Saeidi1, Maryam Ajilian2, Hamid Farhangi3, * Gholam Hasan Khodaei41 1Students Research Committee, Faculty of Medicine, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran. 2 Ibn-e-Sina Hospital, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran. 3 Assistant Professor of Pediatric Oncology, Department of Pediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran. 4Head of the Health Policy Council, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran. Abstract Human rights are the basic standards that people need to live in dignity. In addition to the rights that are available to all people, there are rights that apply only to children. Children need special rights because of their unique needs; they need additional protection that adults don’t. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child is an international document that sets out all of the rights that children have – a child is defined in the Convention as any person under the age of 18. On the other hand Islam recognises family as a basic social unit. Along with the husband-wife relationship the Parent-child relationship is the most important one. To maintain any social relationship both parties must have some clear-cut Rights as well as obligations. The relationships are reciprocal. Duties of one side are the Rights of the other side. So in Parent-child relationship the Rights of parents are the obligations (duties) of the children and vice versa, the Rights of children are obligations (duties) of parents. Islam clearly defines the Rights of Parents (which mean duties of children) and obligations of parents (which means Rights of children). -

Inequality and Development in Nigeria Inequality and Development in Nigeria

INEQUALITY AND DEVELOPMENT IN NIGERIA INEQUALITY AND DEVELOPMENT IN NIGERIA Edited by Henry Bienen and V. P. Diejomaoh HOLMES & MEIER PUBLISHERS, INC' NEWv YORK 0 LONDON First published in the United States of America 1981 by Holmes & Meier Publishers, Inc. 30 Irving Place New York, N.Y. 10003 Great Britain: Holmes & Meier Publishers, Ltd. 131 Trafalgar Road Greenwich, London SE 10 9TX Copyright 0 1981 by Holmes & Meier Publishers, Inc. ALL RIGIITS RESERVIED LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA Political economy of income distribution in Nigeria. Selections. Inequality and development in Nigeria. "'Chapters... selected from The Political economy of income distribution in Nigeria."-Pref. Includes index. I. Income distribution-Nigeria-Addresses, essays, lectures. 2. Nigeria- Economic conditions- Addresses. essays, lectures. 3. Nigeria-Social conditions- Addresses, essays, lectures. I. Bienen. Henry. II. Die jomaoh. Victor P., 1940- III. Title. IV. Series. HC1055.Z91516 1981 339.2'09669 81-4145 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA ISBN 0-8419-0710-2 AACR2 MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Contents Page Preface vii I. Introduction 2. Development in Nigeria: An Overview 17 Douglas Riummer 3. The Structure of Income Inequality in Nigeria: A Macro Analysis 77 V. P. Diejomaoli and E. C. Anusion wu 4. The Politics of Income Distribution: Institutions, Class, and Ethnicity 115 Henri' Bienen 5. Spatial Aspects of Urbanization and Effects on the Distribution of Income in Nigeria 161 Bola A veni 6. Aspects of Income Distribution in the Nigerian Urban Sector 193 Olufemi Fajana 7. Income Distribution in the Rural Sector 237 0. 0. Ladipo and A. -

Muslim American's Understanding of Women's

California State University, San Bernardino CSUSB ScholarWorks Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations Office of aduateGr Studies 6-2018 MUSLIM AMERICAN’S UNDERSTANDING OF WOMEN’S RIGHTS IN ACCORDANCE TO THE ISLAMIC TRADITIONS Riba Khaleda Eshanzada Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd Part of the Social Work Commons Recommended Citation Eshanzada, Riba Khaleda, "MUSLIM AMERICAN’S UNDERSTANDING OF WOMEN’S RIGHTS IN ACCORDANCE TO THE ISLAMIC TRADITIONS" (2018). Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations. 637. https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/etd/637 This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the Office of aduateGr Studies at CSUSB ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses, Projects, and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSUSB ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MUSLIM AMERICAN’S UNDERSTANDING OF WOMEN’S RIGHTS IN ACCORDANCE TO THE ISLAMIC TRADITIONS A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master in Social Work by Riba Khaleda Eshanzada June 2018 MUSLIM AMERICAN’S UNDERSTANDING OF WOMEN’S RIGHTS IN ACCORDANCE TO THE ISLAMIC TRADITIONS A Project Presented to the Faculty of California State University, San Bernardino by Riba Khaleda Eshanzada June 2018 Approved by: Dr. Erica Lizano, Research Project Supervisor Dr. Janet Chang, M.S.W. Research Coordinator © 2018 Riba Khaleda Eshanzada ABSTRACT Islam is the most misrepresented, misunderstood, and the subject for much controversy in the United States of America especially with the women’s rights issue. This study presents interviews with Muslim Americans on their narrative and perspective of their understanding of women’s rights in accordance to the Islamic traditions. -

Al-Shajarah Journal of Islamic Thought and Civilization of the International Islamic University Malaysia (Iium)

AL-SHAJARAH JOURNAL OF ISLAMIC THOUGHT AND CIVILIZATION OF THE INTERNATIONAL ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY MALAYSIA (IIUM) 2019 Volume 24 Number 2 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF ABDELAZIZ BERGHOUT, IIUM, Malaysia EDITORIAL BOARD THAMEEM USHAMA, IIUM, Malaysia MOHAMED ASLAM BIN MOHAMED HANEEF, IIUM, Malaysia Awang SARIYAN, IIUM, Malaysia HAZIZAN MD NOON, IIUM, Malaysia HAFIZ ZAKARIYA, IIUM, Malaysia DANIAL MOHD YUSOF, IIUM, Malaysia ACADEMIC COMMITTEE MD SALLEH Yaapar, USM, Malaysia MOHAMMAD ABDUL QUAYUM, IIUM, Malaysia RAHMAH AHMAD H OSMAN, IIUM, Malaysia RASHID MOTEN, IIUM, Malaysia Spahic OMER, IIUM, Malaysia INTERNATIONAL ADVISORY BOARD SYED ARABI IDID (Malaysia) OSMAN BAKAR (Malaysia/Brunei) ANNABELLE TEH GALLOP (UK) SERDAR DEMIREL (Turkey) AZYUMARDI AZRA (Indonesia) WAEL B. HALLAQ (USA) AFIFI AL-AKITI (Malaysia/UK) IBRAHIM ZEIN (Qatar) Al-Shajarah is a refereed international journal that publishes original scholarly articles in the area of Islamic thought, Islamic civilization, Islamic science, and Malay world issues. The journal is especially interested in studies that elaborate scientific and epistemological problems encountered by Muslims in the present age, scholarly works that provide fresh and insightful Islamic responses to the intellectual and cultural challenges of the modern world. Al-Shajarah will also consider articles written on various religions, schools of thought, ideologies and subjects that can contribute towards the formulation of an Islamic philosophy of science. Critical studies of translation of major works of major writers of the past and present. Original works on the subjects of Islamic architecture and art are welcomed. Book reviews and notes are also accepted. The journal is published twice a year, June-July and November-December. Manuscripts and all correspondence should be sent to the Editor-in-Chief, Al-Shajarah, F4 Building, Research and Publication Unit, International Institute of Islamic Civilisation and Malay World (ISTAC), International Islamic University Malaysia (IIUM), No. -

Women's Rights in Islam Regarding Marriage and Divorce Imani Jaafar-Mohammad

Journal of Law and Practice Volume 4 Article 3 2011 Women's Rights in Islam Regarding Marriage and Divorce Imani Jaafar-Mohammad Charlie Lehmann Follow this and additional works at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/lawandpractice Part of the Family Law Commons Recommended Citation Jaafar-Mohammad, Imani and Lehmann, Charlie (2011) "Women's Rights in Islam Regarding Marriage and Divorce," Journal of Law and Practice: Vol. 4, Article 3. Available at: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/lawandpractice/vol4/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at Mitchell Hamline Open Access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Law and Practice by an authorized administrator of Mitchell Hamline Open Access. For more information, please contact [email protected]. © Mitchell Hamline School of Law Women's Rights in Islam Regarding Marriage and Divorce Keywords Muslim women--Legal status laws etc., Women's rights--Religious aspects--Islam, Marriage (Islamic law) This article is available in Journal of Law and Practice: http://open.mitchellhamline.edu/lawandpractice/vol4/iss1/3 Jaafar-Mohammad and Lehmann: Women's Rights in Islam Regarding Marriage and Divorce WOMEN’S RIGHTS IN ISLAM REGARDING MARRIAGE AND DIVORCE 4 Wm. Mitchell J. L. & P. 3* By: Imani Jaafar-Mohammad, Esq. and Charlie Lehmann+ I. INTRODUCTION There are many misconceptions surrounding women’s rights in Islam. The purpose of this article is to shed some light on the basic rights of women in Islam in the context of marriage and divorce. This article is only to be viewed as a basic outline of women’s rights in Islam regarding marriage and divorce. -

Surah Luqman – Aayaat 12-15

SURAH LUQMAN – AAYAAT 12-15 Interpretation of the Selected Verses Aayaat of Surah Luqman And We had certainly given Luqman wisdom [and said], "Be grateful to Allah." And whoever is grateful is grateful for [the benefit of] himself. And whoever denies [His favor] - then indeed, Allah is Free of need and Praiseworthy. And [mention, O Muhammad], when Luqman said to his son while he was instructing him, "O my son, do not associate [anything] with Allah. Indeed, association [with him] is great injustice." And We have enjoined upon man [care] for his parents. His mother carried him, [increasing her] in weakness upon weakness, and his weaning is in two years. Be grateful to Me and to your parents; to Me is the [final] destination. But if they endeavor to make you associate with Me that of which you have no knowledge, do not obey them but accompany them in [this] world with appropriate kindness and follow the way of those who turn back to Me [in repentance]. Then to Me will be your return, and I will inform you about what you used to do. www.muqith.wordpress.com 1 ISLAMIC STUDIES BLOG Meaning Qur’anic Word S.No. Meaning Qur’anic Word S.No. We have enjoined upon man ِ 12 And We had certainly given 1 َولََقْد آتَ ْي نَا َو َّصْي نَا اْْلن َسا َن His mother carried him 13 Be grateful to Allah ِ ِ 2 ا ْش كْر للَّ ه ََحَلَتْه أ ُّمه Weakness, Difficulty 14 Whoever is grateful 3 َمن يَ ْش كْر َوْهنًا His weaning ِ 15 (is thankful) for his own benefit ِ ِ ِ 4 لنَ ْفسه ف َصال ه Two Years ِ 16 Whoever is Ungrateful 5 َمن َكَفَر َعاَمْي Unto Me is (your) Return! ِ ِ 17 Free of need, Praiseworthy ِ 6 َغِن ي ََحي د إََّل الَْمصي They endeavour to make you 18 He was instructing him ِ 7 يَعظ ه َجاَهَداَك That of which you have no 19 O My Son! 8 ي ب ن ما لَيس لَك بِِه ِعْلم َ ََّ َ ْ َ َ knowledge Then do not obey them ِ 20 Do not associate [anything] with Allah! ِ ِ 9 َل ت ْشِرْك ِبللَّ ه فََل ت طْع هَما Accompany them, Be with them ِ 21 Definitely Injustice 10 لَظ ْلم َصاحْب هَما 11 ع ِظيم Great 22 معروفا Good, kind َ َ ْ ً www.muqith.wordpress.com 2 ISLAMIC STUDIES BLOG. -

Prophet Mohammed's (Pbuh)

1 2 3 4 ﷽ In the name Allah (SWT( the most beneficent Merciful INDEX Serial # Topic Page # 1 Forward 6 2 Names of Holy Qur’an 13 3 What Qur’an says to us 15 4 Purpose of Reading Qur’an in Arabic 16 5 Alphabetical Order of key words in Qura’nic Verses 18 6 Index of Surahs in Qur’an 19 7 Listing of Prophets referred in Qur’an 91 8 Categories of Allah’s Messengers 94 9 A Few Women mentioned in Qur’an 94 10 Daughter of Prophet Mohammed - Fatima 94 11 Mention of Pairs in Qur’an 94 12 Chapters named after Individuals in Qur’an 95 13 Prayers before Sleep 96 14 Arabic signs to be followed while reciting Qur’an 97 15 Significance of Surah Al Hamd 98 16 Short Stories about personalities mentioned in Qur’an 102 17 Prophet Daoud (David) 102 18 Prophet Hud (Hud) 103 19 Prophet Ibrahim (Abraham) 103 20 Prophet Idris (Enoch) 107 21 Prophet Isa (Jesus) 107 22 Prophet Jacob & Joseph (Ya’qub & Yusuf) 108 23 Prophet Khidr 124 24 Prophet Lut (Lot) 125 25 Luqman (Luqman) 125 26 Prophet Musa’s (Moses) Story 126 27 People of the Caves 136 28 Lady Mariam 138 29 Prophet Nuh (Noah) 139 30 Prophet Sho’ayb (Jethro) 141 31 Prophet Saleh (Salih) 143 32 Prophet Sulayman Solomon 143 33 Prophet Yahya 145 34 Yajuj & Majuj 145 5 35 Prophet Yunus (Jonah) 146 36 Prophet Zulqarnain 146 37 Supplications of Prophets in Qur’an 147 38 Those cursed in Qur’an 148 39 Prophet Mohammed’s hadees a Criteria for Paradise 148 Al-Swaidan on Qur’an 149۔Interesting Discoveries of T 40 41 Important Facts about Qur’an 151 42 Important sayings of Qura’n in daily life 151 January Muharram February Safar March Rabi-I April Rabi-II May Jamadi-I June Jamadi-II July Rajab August Sh’aban September Ramazan October Shawwal November Ziqad December Zilhaj 6 ﷽ In the name of Allah, the most Merciful Beneficent Foreword I had not been born in a household where Arabic was spoken, and nor had I ever taken a class which would teach me the language. -

The Islamic Traditions of Cirebon

the islamic traditions of cirebon Ibadat and adat among javanese muslims A. G. Muhaimin Department of Anthropology Division of Society and Environment Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies July 1995 Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] Web: http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Muhaimin, Abdul Ghoffir. The Islamic traditions of Cirebon : ibadat and adat among Javanese muslims. Bibliography. ISBN 1 920942 30 0 (pbk.) ISBN 1 920942 31 9 (online) 1. Islam - Indonesia - Cirebon - Rituals. 2. Muslims - Indonesia - Cirebon. 3. Rites and ceremonies - Indonesia - Cirebon. I. Title. 297.5095982 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by Teresa Prowse Printed by University Printing Services, ANU This edition © 2006 ANU E Press the islamic traditions of cirebon Ibadat and adat among javanese muslims Islam in Southeast Asia Series Theses at The Australian National University are assessed by external examiners and students are expected to take into account the advice of their examiners before they submit to the University Library the final versions of their theses. For this series, this final version of the thesis has been used as the basis for publication, taking into account other changes that the author may have decided to undertake. In some cases, a few minor editorial revisions have made to the work. The acknowledgements in each of these publications provide information on the supervisors of the thesis and those who contributed to its development. -

The Theory of Punishment in Islamic Law a Comparative

THE THEORY OF PUNISHMENT IN ISLAMIC LAW A COMPARATIVE STUDY by MOHAMED 'ABDALLA SELIM EL-AWA Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of London, School of Oriental and African Studies, Department of Law March 1972 ProQuest Number: 11010612 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 11010612 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 2 , ABSTRACT This thesis deals with the theory of Punishment in Islamic law. It is divided into four ch pters. In the first chapter I deal with the fixed punishments or Mal hududrl; four punishments are discussed: the punishments for theft, armed robbery, adultery and slanderous allegations of unchastity. The other two punishments which are usually classified as "hudud11, i.e. the punishments for wine-drinking and apostasy are dealt with in the second chapter. The idea that they are not punishments of "hudud11 is fully ex- plained. Neither of these two punishments was fixed in definite terms in the Qurfan or the Sunna? therefore the traditional classification of both of then cannot be accepted. -

The Punishment of Islamic Sex Crimes in a Modern Legal System the Islamic Qanun of Aceh, Indonesia

CAMMACK.FINAL3 (DO NOT DELETE) 6/1/2016 5:02 PM THE PUNISHMENT OF ISLAMIC SEX CRIMES IN A MODERN LEGAL SYSTEM THE ISLAMIC QANUN OF ACEH, INDONESIA Mark Cammack The role of Islamic law as state law was significantly reduced over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. This decline in the importance of Islamic doctrine has been attributed primarily to the spread of European colonialism. The western powers that ruled Muslim lands replaced much of the existing law in colonized territories with laws modeled after those applied in the home country. The trend toward a narrower role for Islamic law reversed itself in the latter part of the twentieth century. Since the 1970s, a number of majority Muslim states have passed laws prescribing the application of a form of Islamic law on matters that had long been governed exclusively by laws derived from the western legal tradition. A central objective of many of these Islamization programs has been to implement Islamic criminal law, and a large share of the new Islamic crimes that have been passed relate to sex offenses. This paper looks at the enactment and enforcement of recent criminal legislation involving sexual morality in the Indonesian province of Aceh. In the early 2000s, the provincial legislature for Aceh passed a series of laws prescribing punishments for Islamic crimes, the first such legislation in the country’s history. The first piece of legislation, enacted in 2002, authorizes punishment in the form of imprisonment, fine, or caning for acts defined as violating Islamic orthodoxy or religious practice.1 The 2002 statute also established an Islamic police force called the Wilayatul Hisbah charged 1. -

Islamic Law Across Cultural Borders: the Involvement of Western Nationals in Saudi Murder Trials

Denver Journal of International Law & Policy Volume 28 Number 2 Spring Article 3 May 2020 Islamic Law across Cultural Borders: The Involvement of Western Nationals in Saudi Murder Trials Hossin Esmaeili Jeremy Gans Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/djilp Recommended Citation Hossin Esmaeili & Jeremy Gans, Islamic Law across Cultural Borders: The Involvement of Western Nationals in Saudi Murder Trials, 28 Denv. J. Int'l L. & Pol'y 145 (2000). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Denver Journal of International Law & Policy by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. ISLAMIC LAW ACROSS CULTURAL BORDERS: THE INVOLVEMENT OF WESTERN NATIONALS IN SAUDI MURDER TRIALS HOSSEIN ESMAEILI AND JEREMY GANS* I. INTRODUCTION On 11 December 1996, a 51-year-old Australian nurse, Yvonne Gil- ford was found dead in her room in the King Fahd Military Medical Complex in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia.! Within days, two British nurses, Deborah Parry and Lucille McLauchlin, were detained by Saudi au- thorities and later tried and convicted for Gilford's murder.2 These in- cidents spawned a familiar tale of international diplomacy: two gov- ernments, facing conflicting domestic pressures when the nationals of one country are subjected to the laws of another, solve their problem at the executive level once the criminal justice system proceeds to the pu- nitive stage. This culminated in the release of both nurses and their deportation to Britain on May 19 1998.s However, the outcome of the Gilford trial also turned on an unusual legal circumstance: the eventual resolution was dependant on a decision by a citizen of a third country, Frank Gilford, a resident of Australia, whose only connection to the events was that he was the victim's * Dr.