Systematic Inequality: Displacement, Exclusion, and Segregation How America’S Housing System Undermines Wealth Building in Communities of Color

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Race and Membership in American History: the Eugenics Movement

Race and Membership in American History: The Eugenics Movement Facing History and Ourselves National Foundation, Inc. Brookline, Massachusetts Eugenicstextfinal.qxp 11/6/2006 10:05 AM Page 2 For permission to reproduce the following photographs, posters, and charts in this book, grateful acknowledgement is made to the following: Cover: “Mixed Types of Uncivilized Peoples” from Truman State University. (Image #1028 from Cold Spring Harbor Eugenics Archive, http://www.eugenics archive.org/eugenics/). Fitter Family Contest winners, Kansas State Fair, from American Philosophical Society (image #94 at http://www.amphilsoc.org/ library/guides/eugenics.htm). Ellis Island image from the Library of Congress. Petrus Camper’s illustration of “facial angles” from The Works of the Late Professor Camper by Thomas Cogan, M.D., London: Dilly, 1794. Inside: p. 45: The Works of the Late Professor Camper by Thomas Cogan, M.D., London: Dilly, 1794. 51: “Observations on the Size of the Brain in Various Races and Families of Man” by Samuel Morton. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences, vol. 4, 1849. 74: The American Philosophical Society. 77: Heredity in Relation to Eugenics, Charles Davenport. New York: Henry Holt &Co., 1911. 99: Special Collections and Preservation Division, Chicago Public Library. 116: The Missouri Historical Society. 119: The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit, 1882; John Singer Sargent, American (1856-1925). Oil on canvas; 87 3/8 x 87 5/8 in. (221.9 x 222.6 cm.). Gift of Mary Louisa Boit, Julia Overing Boit, Jane Hubbard Boit, and Florence D. Boit in memory of their father, Edward Darley Boit, 19.124. -

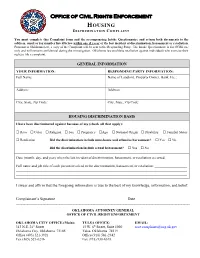

Housing Discrimination Complaint Form

Office of Civil Rights Enforcement HOUSING DISCRIMINATION COMPLAINT You must complete this Complaint form and the accompanying Intake Questionnaire and return both documents to the address, email or fax number listed below within one (1) year of the last incident of discrimination, harassment or retaliation. Pursuant to Oklahoma law, a copy of the Complaint will be sent to the Responding Party. The Intake Questionnaire is for OCRE use only and will remain confidential during the investigation. Oklahoma law prohibits retaliation against individuals who exercise their right to file a complaint. GENERAL INFORMATION YOUR INFORMATION: RESPONDING PARTY INFORMATION: Full Name: Name of Landlord, Property Owner, Bank, Etc.: Address: Address: City, State, Zip Code: City, State, Zip Code: HOUSING DISCRIMINATION BASIS I have been discriminated against because of my (check all that apply): Race Color Religion Sex Pregnancy Age National Origin Disability Familial Status Retaliation Did the discrimination include unwelcome and offensive harassment? Yes No Did the discrimination include sexual harassment? Yes No Date (month, day, and year) when the last incident of discrimination, harassment, or retaliation occurred: ____________ Full name and job title of each person involved in the discrimination, harassment, or retaliation: __________________ _______________________________________________________________________________________________ _______________________________________________________________________________________________ I -

A Partial Historical Timeline of Slavery and Structural Racism in Amherst

A PARTIAL HISTORICAL TIMELINE OF SLAVERY AND STRUCTURAL RACISM IN AMHERST An appendix in support of A RESOLUTION AFFIRMING THE TOWN OF AMHERST’S COMMITMENT TO END STRUCTURAL RACISM AND ACHIEVE RACIAL EQUITY ____________________________________________________________________________ AUTHORING STATEMENT This timeline represents only a small sampling of Amherst’s history of white supremacy, anti-Black racism, and racial inequity. It was compiled by Reparations for Amherst, with research by Amherst resident Mattea Kramer. Cynthia Harbeson, Jones Library Special Collections, and Aaron Rubinstein, Special Collections and University Archives, University of Massachusetts, provided research assistance. This document was created in order to prepare and present evidence and factual information related to historic and contemporary instances where the Town of Amherst might have facilitated, participated, stood neutral, or enacted acts of segregative and discriminatory practices in all aspects of engagement with the Amherst Black community. The intention of this report is to compile, in one cohesive document, published facts from various works, studys, surveys, articles, recordings, policies, and resources that are freely available for public consumption. The authors have worked to compile this information and have cited materials in order to assist others in locating the document’s sources. This report is in progress and will have periodical updates when new information presents itself. VERSION UPDATES October7, 2020 Start date November 6, 2020 Review -

RACIAL SEGREGATION and the ORIGINS of APARTHEID, 1919--36 Racial Segregation and the Origins of Apartheid in South Africa, 1919-36

RACIAL SEGREGATION AND THE ORIGINS OF APARTHEID, 1919--36 Racial Segregation and the Origins of Apartheid in South Africa, 1919-36 Saul Dubow, 1989 Palgrave Macmillan ISBN 978-1-349-20043-6 ISBN 978-1-349-20041-2 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-1-349-20041-2 © Saul Dubow, 1989 Softcover reprint ofthe hardcover Ist edition 1989 All rights reserved. For information, write: Scholarly and Reference Division, St. Martin's Press, Inc., 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010 First published in the United States of America in 1989 ISBN 978-0-312-02774-2 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Racial segregation and the origins of apartheid in South Africa. 1919-36/ Sau1 Dubow. p. cm. Bibliography: p. Includes index. ISBN 978-0-312-02774-2 1. Apartheid-South Africa-History-20th century. I. Dubow, Saul. DT763.R34 1989 88-39594 968.05'3--dc19 CIP Contents Pre/ace vii List 0/ Abbreviations x Introduction 1 PART I 1 The Elaboration of Segregationist Ideology, c. 1900-36 21 1 Early Exponents of Segregation 21 2 'Cultural Adaptation' 29 3 Segregation after the First World War 39 4 The Liberal Break with Segregation 45 2 Segregation and Cheap Labour 51 1 The Cheap-Iabour Thesis 51 2 The Mines 53 3 White Labour 56 4 Agriculture 60 5 The Reserves 66 6 An Emergent Proletariat 69 PART 11 3 Structure and Conßict in the Native Affairs Department 77 1 The Native Affairs Department (NAD) 77 2 Restructuring the NAD: the Public Service Commission, 1922-3 81 3 Conftict within the State and the Native Administration Bill ~ 4 'Efficiency', 'Economy' and 'Flexibility' -

What Anti-Miscegenation Laws Can Tell Us About the Meaning of Race, Sex, and Marriage," Hofstra Law Review: Vol

Hofstra Law Review Volume 32 | Issue 4 Article 22 2004 Love with a Proper Stranger: What Anti- Miscegenation Laws Can Tell Us About the Meaning of Race, Sex, and Marriage Rachel F. Moran Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Moran, Rachel F. (2004) "Love with a Proper Stranger: What Anti-Miscegenation Laws Can Tell Us About the Meaning of Race, Sex, and Marriage," Hofstra Law Review: Vol. 32: Iss. 4, Article 22. Available at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlr/vol32/iss4/22 This document is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hofstra Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Moran: Love with a Proper Stranger: What Anti-Miscegenation Laws Can Tel LOVE WITH A PROPER STRANGER: WHAT ANTI-MISCEGENATION LAWS CAN TELL US ABOUT THE MEANING OF RACE, SEX, AND MARRIAGE Rachel F. Moran* True love. Is it really necessary? Tact and common sense tell us to pass over it in silence, like a scandal in Life's highest circles. Perfectly good children are born without its help. It couldn't populate the planet in a million years, it comes along so rarely. -Wislawa Szymborskal If true love is for the lucky few, then for the rest of us there is the far more mundane institution of marriage. Traditionally, love has sat in an uneasy relationship to marriage, and only in the last century has romantic love emerged as the primary, if not exclusive, justification for a wedding in the United States. -

Read the Transcript

>> I just moved to a new city. I just moved to a new city. And finding a decent place to live was a real challenge. I mean, there are so many hoops to jump through. But just a couple of generations ago, there were even more barriers for someone who looks like me. I didn't see any "whites only" signs at the open house. When I went to sign the contract, the landlord didn't lie to me and tell me the apartment was already rented to someone else. Before President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Fair Housing Bill in 1968, that kind of craziness was totally legal. Landlords could refuse to sell or rent housing because of someone's race, color, religion, sex, family status, national origin, or pretty much any reason. But the Fair Housing Act changed all of that, right? It eliminated housing discrimination, fostered integration, pretty much solved all of our problems. Eh, not so much. So what does that mean for us? What is the impact of housing discrimination today? Let's take a step back. Near the end of the Civil War, General William T. Sherman wanted to set aside land for formerly enslaved families so they weren't starting from scratch. The rallying cry was "40 acres and a mule." But it never happened. Lincoln was assassinated. And Sherman's order was revoked. In spite of this, black communities started to advance. There were black newspapers, black-owned businesses, even black senators within a decade of the end of the Civil War. -

The Color of Law a Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America

The Color of Law A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America by Richard Rothstein An explosive, alarming history that finally confronts how American governments in the twentieth century deliberately imposed residential racial segregation on metropolitan areas nationwide. “The Color of Law is one of those rare books that will be discussed and debated for many decades. Based on careful analyses of multiple historical documents, Rothstein has presented what I consider to be the most forceful argument ever published on how federal, state and local governments gave rise to and reinforced neighborhood segregation.” —WILLIAM JULIUS WILSON, author of The Truly Disadvantaged “Richard Rothstein’s The Color of Law offers an original and insightful explanation of how government policy in the United States intentionally promoted and enforced residential racial segregation. …[H]is argument, which calls for a fundamental reexamination of American constitutional law, is that the Supreme Court has failed for decades to understand the extent to which residential racial segregation in our nation is not the result of private decisions…, but is the direct product of unconstitutional government action. The implications of his analysis are revolutionary.” —GEOFFREY R. STONE, Professor of Law (and former dean) at the University of Chicago Law School “While the road forward is far from clear, there is no better history of this troubled journey than The Color of Law.” —DAVID OSHINSKY, Professor of History at New York University, in The New York Times Book Review “A masterful explication of the single most vexing problem facing black America: the concentration of the poor and middle class into segregated neighborhoods. -

Housing-Related Hate Activity

Housing-Related Hate Activity National Fair Housing Alliance Agenda • Fair Housing Act’s prohibition against housing-related hate activity • Responding to housing-related hate activity – Forming a response network – Rapid response protocols Fair Housing Act • Title VIII of Civil Rights Act of 1968 • Prohibits discrimination in housing-related transactions because of: –Race – Color – Religion – National origin –Sex – Disability – Familial status (children under age 18 in household) Housing Discrimination • Any attempt to prohibit or limit free and fair housing choice because of a protected class • Applies to all housing-related transactions – Rentals – Real estate sales – Mortgage lending – Appraisals – Homeowners insurance – Zoning Housing-Related Hate Activity • Unlawful to coerce, intimidate, threaten, or interfere with any person in the exercise or enjoyment of fair housing rights, such as: – Renting or buying a house – Reasonable accommodations/modifications – Filing a fair housing complaint • Unlawful to retaliate against someone for exercising fair housing rights – Or for helping another person exercise fair housing rights • 42 U.S.C. § 3617 HUD Regulation • 24 C.F.R. § 100.400 • Unlawful to: – Threaten, intimidate, or interfere with persons in their enjoyment of a dwelling because of their protected class or the protected class of visitors/associates – Intimidate or threaten any person because that person is engaging in activities designed to make other persons aware of, or encouraging such other persons to exercise, fair housing -

Housing Discrimination Against Victims of Domestic Violence

Housing Discrimination Against Victims of Domestic Violence By Wendy R. Weiser and Geoff Boehm In their government-subsidized two-bed- The notice referred to the August 2 incident room apartment on the morning of August in which Ms. Alvera was injured.1 2, 1999, Tiffanie Ann Alvera’s husband Ms. Alvera’s story is not an aberra- physically assaulted her. The police arrest- tion. Women across the country are ed him, placed him in jail, and charged denied housing opportunities or evicted him with assault. He was eventually con- from their housing simply because they victed. That same day, after receiving med- are victims of domestic violence.2 Land- ical treatment for the injuries her husband lords who deny housing to victims of inflicted, Ms. Alvera went to Clatsop domestic violence not only heap further County Circuit Court and obtained a punishment on innocent victims but also restraining order prohibiting him from help cement the cycle of violence. By coming near her or into the apartment forcing victims to make the terrible choice complex where they lived. When she gave between suffering in silence and losing the resident manager of the apartment their housing, those landlords effectively complex a copy of the restraining order, discourage victims from reporting their she was told that the management com- abuse or otherwise taking steps to pro- pany had decided to evict her as a result tect themselves. Those victims who do of the incident of domestic violence. Two undertake to protect themselves find it days later Ms. Alvera’s landlord served her much more difficult to achieve indepen- with a twenty-four-hour notice terminat- dence from their abusers when they are ing her tenancy. -

Complementary International Standards First Session Geneva, 11-22 February 2008

UNITED NATIONS A General Assembly Distr. GENERAL A/HRC/AC.1/1/CRP.4 18 February 2008 Original: ENGLISH ONLY HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL Ad Hoc Committee on the Elaboration of Complementary International Standards First session Geneva, 11-22 February 2008 COMPLEMENTARY INTERNATIONAL STANDARDS COMPILATION OF CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS OF THE STUDY BY THE FIVE EXPERTS ON THE CONTENT AND SCOPE OF SUBSTANTIVE GAPS IN THE EXISTING INTERNATIONAL INSTRUMENTS TO COMBAT RACISM RACIAL DISCRIMINATION, XENOPHOBIA AND RELATED INTOLERANCE A/HRC/AC.1/1/CRP.4 Page 2 I. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS ON THE CONTENT AND SCOPE OF SUBSTANTIVE GAPS ON COMPLEMENTARY INTERNATIONAL STANDARDS WITH REGARD TO POSITIVE OBLIGATIONS OF STATES PARTIES Assessment and recommendations 1. The role of human rights education 29. The DDPA underlines the importance of human rights education as a key to changing attitudes and behaviour and to promoting tolerance and respect for diversity in societies1 and, therefore as crucial in the struggle against racism, racial discrimination, xenophobia and related intolerance.2 The importance of human rights education is also underlined in several other human rights documents. The Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action assert that “human rights education, training and public information are essential for the promotion and achievement of stable and harmonious relations among communities and for fostering mutual understanding, tolerance and peace.”3 The World Programme for Human Rights Education identifies the promotion of understanding, tolerance, gender equality and friendship among all nations, indigenous peoples and racial, national, ethnic, religious and linguistic groups as one of the constitutive elements of human rights education that aims at building a universal culture of human rights.4 The 2005 World Summit Outcome calls for the implementation of the World Programme for Human Rights Education and encourages all States to develop initiatives in this regard.5 30. -

Heteropatriarchy and the Three Pillars of White Supremacy Rethinking Women of Color Organizing

Heteropatriarchy and the Three Pillars of White Supremacy Rethinking Women of Color Organizing Andrea Smith Scenario #1 A group of women of color come together to organize. An argu- ment ensues about whether or not Arab women should be included. Some argue that Arab women are "white" since they have been classified as such in the US census. Another argument erupts over whether or not Latinas qualify as "women of color," since some may be classified as "white" in their Latin American countries of origin and/or "pass" as white in the United States. Scenario #2 In a discussion on racism, some people argue that Native peoples suffer from less racism than other people of color because they gen- erally do not reside in segregated neighborhoods within the United States. In addition, some argue that since tribes now have gaming, Native peoples are no longer "oppressed." Scenario #3 A multiracial campaign develops involving diverse conpunities of color in which some participants charge that we must stop the blacklwhite binary, and end Black hegemony over people of color politics to develop a more "multicultural" framework. However, this campaign continues to rely on strategies and cultural motifs developed by the Black Civil Rights struggle in the United States. These incidents, which happen quite frequently in "women of color" or "pee;' of color" political organizing struggles, are often explained as a consequenii. "oppression olympics." That is to say, one problem we have is that we are too b::- fighting over who is more oppressed. In this essay, I want to argue that thescir- dents are not so much the result of "oppression olympics" but are more abour t-, we have inadequately framed "women of color" or "people of color" politics. -

Report for Greenwood District Tulsa, Tulsa County, Oklahoma

REPORT FOR GREENWOOD DISTRICT TULSA, TULSA COUNTY, OKLAHOMA The 100-block of North Greenwood Avenue, June 1921, Mary E. Jones Parrish Collection, Oklahoma Historical Society PREPARED FOR THE INDIAN NATIONS COUNCIL OF GOVERNMENTS, ON BEHALF OF THE TULSA PRESERVATION COMMISSION, CITY OF TULSA 2 WEST 2ND STREET, SUITE 800, TULSA, OKLAHOMA 74103 BY PRESERVATION AND DESIGN STUDIO PLLC 616 NW 21ST STREET, OKLAHOMA CITY, OK 73103 MAY 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Abstract ...................................................................................................4 2 Introduction ..............................................................................................6 3 Research Design .......................................................................................9 4 Project Objectives ....................................................................................9 5 Methodology ............................................................................................10 6 Expected Results ......................................................................................13 7 Area Surveyed ..........................................................................................14 8 Historic Context .......................................................................................18 9 Survey Results .........................................................................................27 10 Bibliography ............................................................................................36 APPENDICES Appendix