Control Over Multiple Forms of Instructional Assistance While Learning the Cascade Juggle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Midwest Flow Fest Workshop Descriptions!

Ping Tom Memorial Park Chicago, IL Saturday, September 9 Area 1 Area 2 Area 3 Area 4 FREE! Intro Contact Mini Hoop Technicality VTG 1:1 with Fans Tutting for Flow Art- 11am Jay Jay Kassandra Morrison Jessica Mardini Dushwam Fancy Feet FREE! Poi Basics Performance 101 No Beat Tosses 12:30pm Perkulator Jessie Wags Matt O’Daniel Zack Lyttle FREE! Intro to Fans Better Body Rolls Clowning Around Down & Dirty- 2pm Jessica Mardini Jacquie Tar-foot Jared the Juggler Groundwork- Jay Jay Acro Staff 101 Buugeng Fundamentals Modern Dance Hoop Flowers Shapes & Hand 3:30pm Admiral J Brown Kimberly Bucki FREE! Fearless Ringleader Paths- Dushwam Inclusive Community Swap Tosses 3 Hoop Manipulation Tosses with Doubles 5pm Jessica Mardini FREE! Zack Lyttle Kassandra Morrison Exuro 6:30pm MidWest Flow Fest Instructor Showcase Sunday, September 10 Area 1 Area 2 Area 3 Area 4 Contact Poi 1- Intro Intro to Circle Juggle Beginner Pole Basics Making Organic 11am Matt O’Daniel FREE! Juan Guardiola Alice Wonder Sequences - Exuro Intermediate Buugeng FREE! HoopDance 101 Contact Poi 2- Full Performance Pro Tips 12:30pm Kimberly Buck Casandra Tanenbaum Contact- Matt O’Daniel Fearless Ringleader FREE! Body Balance Row Pray Fishtails Lazy Hooping Juggling 5 Ball 2pm Jacqui Tar-Foot Admiral J Brown Perkulator Jared the Juggler 3:30pm Body Roll Play FREE! Fundamentals: Admiral’s Way Contact Your Prop, Your Kassandra Morrison Reels- Dushwam Admiral J Brown Dance- Jessie Wags 5pm FREE! Cultivating Continuous Poi Tosses Flow Style & Personality Musicality in Motion Community- Exuro Juan Guardiola Casandra Tanenbaum Jacquie Tar-Foot 6:30pm MidWest Flow Fest Jam! poi dance/aerial staff any/all props juggling/other hoop Sponsored By: Admiral J. -

The Effects of Balance Training on Balance Ability in Handball Players

EXERCISE AND QUALITY OF LIFE Research article Volume 4, No. 2, 2012, 15-22 UDC 796.322-051:796.012.266 THE EFFECTS OF BALANCE TRAINING ON BALANCE ABILITY IN HANDBALL PLAYERS Asimenia Gioftsidou , Paraskevi Malliou, Polina Sofokleous, George Pafis, Anastasia Beneka, and George Godolias Department of Physical Education and Sports Science, Democritus University of Thrace, Komotini, Greece Abstract The purpose of the present study was to investigate, the effectiveness of a balance training program in male professional handball players. Thirty professional handball players were randomly divided into experimental and control group. The experimental group (N=15), additional to the training program, followed an intervention balance program for 12 weeks. All subjects performed a static balance test (deviations from the horizontal plane). The results revealed that the 12-week balance training program improved (p<0.01) all balance performance indicators in the experimental group. Thus, a balance training program can increase balance ability of handball players, and could used as a prevent tool for lower limbs muscular skeletal injuries. Keywords: handball players, proprioception, balance training Introduction Handball is one of the most popular European team sports along with soccer, basketball and volleyball (Petersen et al., 2005). The sport medicine literature reports team sports participants, such as handball, soccer, hockey, or basketball players, reported an increased risk of traumatic events, especially to their lower extremity joints (Hawkins, and Fuller, 1999; Meeuwisse et al., 2003; Wedderkopp et al 1997; 1999). Injuries often occur in noncontact situations (Hawkins, and Fuller, 1999; Hertel et al., 2006) resulting in substantial and long-term functional impairments (Zech et al., 2009). -

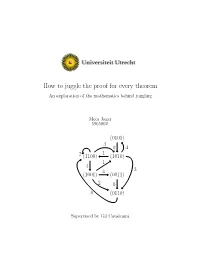

How to Juggle the Proof for Every Theorem an Exploration of the Mathematics Behind Juggling

How to juggle the proof for every theorem An exploration of the mathematics behind juggling Mees Jager 5965802 (0101) 3 0 4 1 2 (1100) (1010) 1 4 4 3 (1001) (0011) 2 0 0 (0110) Supervised by Gil Cavalcanti Contents 1 Abstract 2 2 Preface 4 3 Preliminaries 5 3.1 Conventions and notation . .5 3.2 A mathematical description of juggling . .5 4 Practical problems with mathematical answers 9 4.1 When is a sequence jugglable? . .9 4.2 How many balls? . 13 5 Answers only generate more questions 21 5.1 Changing juggling sequences . 21 5.2 Constructing all sequences with the Permutation Test . 23 5.3 The converse to the average theorem . 25 6 Mathematical problems with mathematical answers 35 6.1 Scramblable and magic sequences . 35 6.2 Orbits . 39 6.3 How many patterns? . 43 6.3.1 Preliminaries and a strategy . 43 6.3.2 Computing N(b; p).................... 47 6.3.3 Filtering out redundancies . 52 7 State diagrams 54 7.1 What are they? . 54 7.2 Grounded or Excited? . 58 7.3 Transitions . 59 7.3.1 The superior approach . 59 7.3.2 There is a preference . 62 7.3.3 Finding transitions using the flattening algorithm . 64 7.3.4 Transitions of minimal length . 69 7.4 Counting states, arrows and patterns . 75 7.5 Prime patterns . 81 1 8 Sometimes we do not find the answers 86 8.1 The converse average theorem . 86 8.2 Magic sequence construction . 87 8.3 finding transitions with flattening algorithm . -

Inspiring Mathematical Creativity Through Juggling

Journal of Humanistic Mathematics Volume 10 | Issue 2 July 2020 Inspiring Mathematical Creativity through Juggling Ceire Monahan Montclair State University Mika Munakata Montclair State University Ashwin Vaidya Montclair State University Sean Gandini Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Mathematics Commons Recommended Citation Monahan, C. Munakata, M. Vaidya, A. and Gandini, S. "Inspiring Mathematical Creativity through Juggling," Journal of Humanistic Mathematics, Volume 10 Issue 2 (July 2020), pages 291-314. DOI: 10.5642/ jhummath.202002.14 . Available at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm/vol10/iss2/14 ©2020 by the authors. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License. JHM is an open access bi-annual journal sponsored by the Claremont Center for the Mathematical Sciences and published by the Claremont Colleges Library | ISSN 2159-8118 | http://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm/ The editorial staff of JHM works hard to make sure the scholarship disseminated in JHM is accurate and upholds professional ethical guidelines. However the views and opinions expressed in each published manuscript belong exclusively to the individual contributor(s). The publisher and the editors do not endorse or accept responsibility for them. See https://scholarship.claremont.edu/jhm/policies.html for more information. Inspiring Mathematical Creativity Through Juggling Ceire Monahan Department of Mathematical Sciences, Montclair State University, New Jersey, USA -

Happy Birthday!

THE THURSDAY, APRIL 1, 2021 Quote of the Day “That’s what I love about dance. It makes you happy, fully happy.” Although quite popular since the ~ Debbie Reynolds 19th century, the day is not a public holiday in any country (no kidding). Happy Birthday! 1998 – Burger King published a full-page advertisement in USA Debbie Reynolds (1932–2016) was Today introducing the “Left-Handed a mega-talented American actress, Whopper.” All the condiments singer, and dancer. The acclaimed were rotated 180 degrees for the entertainer was first noticed at a benefit of left-handed customers. beauty pageant in 1948. Reynolds Thousands of customers requested was soon making movies and the burger. earned a nomination for a Golden Globe Award for Most Promising 2005 – A zoo in Tokyo announced Newcomer. She became a major force that it had discovered a remarkable in Hollywood musicals, including new species: a giant penguin called Singin’ In the Rain, Bundle of Joy, the Tonosama (Lord) penguin. With and The Unsinkable Molly Brown. much fanfare, the bird was revealed In 1969, The Debbie Reynolds Show to the public. As the cameras rolled, debuted on TV. The the other penguins lifted their beaks iconic star continued and gazed up at the purported Lord, to perform in film, but then walked away disinterested theater, and TV well when he took off his penguin mask into her 80s. Her and revealed himself to be the daughter was actress zoo director. Carrie Fisher. ©ActivityConnection.com – The Daily Chronicles (CAN) HURSDAY PRIL T , A 1, 2021 Today is April Fools’ Day, also known as April fish day in some parts of Europe. -

JUGGLING in the U.S.S.R. in November 1975, I Took a One Week Tour to Leningrad and Ring Cascade Using a "Holster” at Each Side

Volume 28. No. 3 March 1976 INTERNATIONAL JUGGLERS ASSOCIATION from Roger Dol/arhide JUGGLING IN THE U.S.S.R. In November 1975, I took a one week tour to Leningrad and ring cascade using a "holster” at each side. He twice pretended Moscow, Russia. I wasfortunate to see a number of jugglers while to accidentally miss the catch of all 9 down over his head before I was there. doing it perfectly to rousing applause and an encore bow. At the Leningrad Circus a man approximately 45 years old did Also on the show was a lady juggler who did a short routine an act which wasn’t terribly exciting, though his juggling was spinning 15-inch square glass sheets. She finished by spinning pretty good. He did a routine with 5, 4, 3 sticks including one on a stick balanced on her forehead and one on each hand showering the 5. He also balanced a pole with a tray of glassware simultaneously. Then, she did the routine of balancing a tray of on his head and juggled 4 metaf plates. For a finish, he cqnter- glassware on a sword balanced point to point on a dagger in her spun a heavy-looking round wooden table upside-down on a 10- mouth and climbing a swaying ladder ala Rosana and others. foot sectioned pole balanced on his forehead, then knocked the Finally, there were two excellent juggling acts as part of a really pole away and caught the table still spinning on a short pole held great music and variety floor show at the Arabat Restaurant in in his hands. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Flips and Juggles A

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Flips and Juggles ADissertationsubmittedinpartialsatisfactionofthe requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Mathematics by Jay Cummings Committee in charge: Professor Ron Graham, Chair Professor Jacques Verstra¨ete, Co-Chair Professor Fan Chung Professor Shachar Lovett Professor Je↵Remmel Professor Alexander Vardy 2016 Copyright Jay Cummings, 2016 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Jay Cummings is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on micro- film and electronically: Co-Chair Chair University of California, San Diego 2016 iii DEDICATION To mom and dad. iv EPIGRAPH We’ve taught you that the Earth is round, That red and white make pink. But something else, that matters more – We’ve taught you how to think. — Dr. Seuss v TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page . iii Dedication . iv Epigraph ...................................... v TableofContents.................................. vi ListofFigures ................................... viii List of Tables . ix Acknowledgements ................................. x AbstractoftheDissertation . xii Chapter1 JugglingCards ........................... 1 1.1 Introduction . 1 1.1.1 Jugglingcardsequences . 3 1.2 Throwingoneballatatime . 6 1.2.1 The unrestricted case . 7 1.2.2 Throwingeachballatleastonce . 9 1.3 Throwing m 2ballsatatime. 16 1.3.1 A digraph≥ approach . 17 1.3.2 Adi↵erentialequationsapproach . 21 1.4 Throwing di↵erent numbers of balls at di↵erent times . 23 1.4.1 Boson normal ordering . 24 1.5 Preserving ordering while throwing . 27 1.6 Juggling card sequences with minimal crossings . 32 1.6.1 A reduction bijection with Dyck Paths . 36 1.6.2 A parenthesization bijection with Dyck Paths . 48 1.6.3 Non-crossingpartitions . 52 1.6.4 Counting using generating functions . -

19730007257.Pdf

fit ENG A SPECIAL BIBLIOGRAJ'HY / V '^x £'* "" •' V: WITH INDEXES $'. - • ''? Supplement 23 "13 Ks oo oc NATIONAL AERONAUTICS AND SPACE ADMINISTRATION PREVIOUS BIBLIOGRAPHIES IN THIS SERIES ftttCUftWIt! NASA SP-703? September 1970 Jan.-Aug. |9?0 NASA SP-7037 (Oh Januarv 1971 Sept.-Dec. 1970 NASA SP-7037 f 02) Februar> 1971 January 1971 NASA SP-7037(U3» March 1*971 K'briiarv 1971 NASA April |V?1 March 1971 NASA SP-7037 f 05) Ma> 1971 April |97| , NASA SP-7037 »06) June 1971 Ma> 1971 NASA SP-7037 «. i?) Jul\ !*»?! June 1971 NASA SP-7037 (08) Auuu\t 197! Julv 19" I NASA SP-7037 (09) September 1971 August 1971 ,NASA SP-7037 (10) October 1971 September 1971 'NASA SP- 7037(1 1) November 1971 October 1971 NASA SP-7037 (12) December 1971 November 197! NASA SP-7037 (13) JUmuur> 1972 December 1971 NASA SP-7037 (14} January 1972 Annual Indexes 197J NASA SP-7037 (15) February 19t2 January 1972 NASA SP-7037 (16) March 1972 February 1972 NASA SP-7037 (17) April 1972 March 1972 NASA SP-7037 (18) May 1972 April 1972 NASA SP-7037 (19) June 1972 May 1972 NASA SP-7037 (20) July 1972 June 1972 . NASA SP-7037 (2 1) August 1972 July 1972 NASA SP-7037 (22) September 1972 Aueust 1972 Thi> bibliography w-as prepared by the NAS\ Scientific jnd Tt-'chnical information Fac»Hl\ for the National Aeronautic* j«d Space -Vdmini^ration b\ Informatics Th>co, Inc. The Administrator of the Nat'Onaf Aeronautics and Space Admimsration Has determined that tfte pubiicatjon of this persodtcai is neeessa«y in the transaction of the public business rsqui'ea by law of this Agency. -

Aircraft Weight and Balance Control

AC 120-27D DATE: 8/11/04 Initiated By: AFS-200/ AFS-300 ADVISORY CIRCULAR AIRCRAFT WEIGHT AND BALANCE CONTROL U.S. DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION Federal Aviation Administration Flight Standards Service Washington, D.C. 8/11/04 AC 120-27D TABLE OF CONTENTS Paragraph Page CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................1 100. What is the purpose of this advisory circular (AC)?.......................................................1 101. How is this AC organized? .............................................................................................1 102. What documents does this AC cancel?...........................................................................1 103. What should an operator consider while reading this AC?.............................................2 104. Who should use this AC?................................................................................................2 Table 1-1. Aircraft Cabin Size ................................................................................................2 105. Who can use standard average or segmented weights? ..................................................2 CHAPTER 2. AIRCRAFT WEIGHTS AND LOADING SCHEDULES......................................5 Section 1. Establishing Aircraft Weight .................................................................................... 5 200. How does an operator establish the initial weight of an aircraft?...................................5 201. How does an -

Annual Report 2020

ANNUAL REPORT 2020 HASKELL INDIAN NATIONS UNIVERSITY Table of Contents 03 President’s Welcome 04 Student Demographics: 2019-20 05 Student Demographics: 2019-20 (cont.) 06 Students of the Year: AICF & HINU 07 Class of 2015 Alumni Spotlight 08 Class of 2010 Alumni Spotlight 09 Class of 2010 Alumni Spotlight 10 Financial Aid: 2019-20 & Stewardship: 2019-20 11 Institutional Values—Goals Contact Information Haskell Indian Nations University 155 Indian Avenue Lawrence, KS 66046 (785) 749-8497 www.haskell.edu Office of the President (785) 749-7497 Dr. Tamara Pfeiffer (Interim) [email protected] Vice-President of University Services (785) 749-8457 Tonia Salvini [email protected] Vice-President of Academics (785) 749-8494 Cheryl Chuckluck (Interim) [email protected] Office of Admissions (785) 749-8456 Dorothy Stites [email protected] Office of the Registrar (785) 749-8440 Lou Hara [email protected] Financial Aid Office (785) 830-2702 Carlene Morris [email protected] Athletics Department (785) 749-8459 Gary Tanner (Interim) [email protected] Facilities Management (785) 830-2784 Karla Van Noy (Interim) [email protected] 2019-2020: Unexpected challenges Dr. Ronald Graham, President Eastern Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma To all our stakeholders, Among the unexpected challenges of the 2019-2020 academic year has been the challenge of finding words to adequately describe it. This has been a year like no other. The COVID-19 pandemic reinforced the impact of our individual actions on those around us. In response, we renewed our commitment as a University to taking personal responsibility for our actions to ensure the health and well-being of others. -

In-Jest-Study-Guide

with Nels Ross “The Inspirational Oddball” . Study Guide ABOUT THE PRESENTER Nels Ross is an acclaimed performer and speaker who has won the hearts of international audiences. Applying his diverse background in performing arts and education, Nels works solo and with others to present school assemblies and programs which blend physical theater, variety arts, humor, and inspiration… All “in jest,” or in fun! ABOUT THE PROGRAM In Jest school assemblies and programs are based on the underlying principle that every person has value. Whether highlighting character, healthy choices, science & math, reading, or another theme, Nels employs physical theater and participation to engage the audience, juggling and other variety arts to teach the concepts, and humor to make it both fun and memorable. GOALS AND OBJECTIVES This program will enhance awareness and appreciation of physical theater and variety arts. In addition, the activities below provide connections to learning standards and the chosen theme. (What theme? Ask your artsineducation or assembly coordinator which specific program is coming to your school, and see InJest.com/schoolassemblyprograms for the latest description.) GETTING READY FOR THE PROGRAM ● Arrange for a clean, well lit SPACE, adjusting lights in advance as needed. Nels brings his own sound system, and requests ACCESS 4560 minutes before & after for set up & take down. ● Make announcements the day before to remind students and staff. For example: “Tomorrow we will have an exciting program with Nels Ross from In Jest. Be prepared to enjoy humor, juggling, and stunts in this uplifting celebration!” ● Discuss things which students might see and terms which they might not know: Physical Theater.. -

HISTORY and STAGE METHOD of JUGGLING with HULA HOOPS Oleksandra Sobolieva Kyiv Municipal Academy of Circus and Variety Arts, Kiev, Ukraine

INNOVATIVE SOLUTIONS IN MODERN SCIENCE № 2(11), 2017 UDC 792 (792.7) HISTORY AND STAGE METHOD OF JUGGLING WITH HULA HOOPS Oleksandra Sobolieva Kyiv Municipal Academy of Circus and Variety Arts, Kiev, Ukraine Research the methods of teaching juggling tricks by the big and small hula hoops, due to rising demand for hula hoops in recent years. Hula hoops acquire much popularity both abroad and in Ukraine, and are used not only in school, gymnastics and emotional pleasure, but also in a circus and juggling sports. Also highlights the main directions in the juggling with their features and how the juggling acts itself directly on human health. Also will be examined where this fascinating art form came to us, how it developed, and what kinds acquired in the present. Keywords: hula hoops, juggling, "track", stage technique, white substance, "helicopter". Problem definition and analysis of researches. Today juggling reached incredible development. There is no country where people would not be interested in juggling. There are a lot of conventions and juggling competitions, where people come from all over the world and share experiences with each other. But it should be noted, that there aren’t so much professional juggling schools. And if we talk about juggling by hula hoops, we can admit that there aren’t so much real experts in this field. Peter Bon, Tony Buzan in collaboration with Michael J. Gelb, Luke Burridge, Alexander Kiss, Paul Koshel and many others have written about all kinds of juggling, but left unattended hula hoops juggling. That is why in this article will be examples of author’s tricks with large and small hula hoops with a detailed description.