Improbable Adventures of Sherlock Holmes Comprised of Eight

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Roger Johnson, Mole End, 41 Sandford Road, Chelmsford CM2 6DE E-Mail: [email protected] No

THE NEWSLETTER OF THE SHERLOCK HOLMES SOCIETY OF LONDON Roger Johnson, Mole End, 41 Sandford Road, Chelmsford CM2 6DE e-mail: [email protected] no. 344 30 July 2014 The subscription for postal subscribers who send money rather than Sheldon Reynolds’ 1954 TV series, and Shane Peacock on writing his stamped & self-addressed envelopes is (for 12 issues) £7.50 in the The Boy Sherlock Holmes novels. There are also interviews with the UK, and £12.00 or US$21.00 overseas. Please make dollar checks creators of the Young Sherlock Holmes Adventures graphic novels, the payable to The Sherlock Holmes Society of London . Prices went up co-author of the Sherlock Holmes: Year One graphic novels, and the in March, and I’ve borne the increase since then. An e-mail authors of Steampunk Holmes: Legacy of the Nautilus , Dead Man’s subscription costs nothing and pretty much guarantees instantaneous Land and The House of Silk . It’s a rich, varied and most interesting delivery. mixture – let down, curiously, by an unnecessarily small sans serif font in the main articles. As we know, Undershaw has been saved from the worst sort of inappropriate ‘development’. After long years of neglect, the house at The ‘Professor Moriarty’ novels by Michael Kurland , which began Hindhead, one of only two in England designed in part by a major in 1978 with The Infernal Device , are at last being published in the author for himself, has been bought by the DFN Charitable UK, thanks to Titan Books. The third, The Great Game , appeared this Foundation, and will become the upper school of Stepping Stones, a month, thirteen years after its US publication (Titan; titanbooks.com ; school for children with a range of special needs. -

My Own 221B Baker Street ”To a Great Mind Nothing Is Little” (STUD)

My Own 221B Baker Street ”To a great mind nothing is little” (STUD) PLANNING AND BUILDING For forty years I had toyed with the idea of making myself a full-scale replica of the most famous room in the world literature, the legendary snug , unconventional sitting room at 221B Baker Street in London where most of the wonderful Sherlock Holmes adventures begin and where the reader, embedded in safe fellowship, listens to the detective revealing his remarkable clues to his dedicated friend Dr Watson while the eternal smoke from his pipe curles against the ceiling. However, on my own retirement we moved to a rather small terrace house and I had to drop the idea. I then suddenly remembered a fine letter from my friend John Bennett Shaw 1 where he temptingly describes the 221B miniature that his wife Dorothy had made for him, and realized that I could build my own scale model. Now, twelve years later, I can hardly think of anything more pleasant than a hobby including cultural and literary research, miniature handicraft and collecting. After having read the Holmes stories once again -- this time taking careful notes -- I started with a design draft. My proper scale would be the English 1:12, one inch to one foot. And my model should at least exibit the ground floor and the second floor of the famous three-storied Baker Street house. When musing about the dimensions of the house I decided on two criteria: The stairs leading up to the second floor must consist of seventeen steps2 and the sitting room had to be large enough to hold all the furniture that is mentioned in the stories3. -

Issue #53 Spring 2006

T HE NORWEGIAN EXPLORERS OF MINNESOTA, INC. ©2006 Winter, 2006 EXPLORATIONS Issue #53 EXPLORATIONSEXPLORATIONS From the (Outgoing) President . Julie McKuras, ASH, BSI Inside this issue: Internet Explorations 2 Annual Meeting & Dinner 3 Explorer Travels 4 A New Take on Mrs. Hudson 5 Holmes and Plastic Man? 6 The English 8 A Toast to Mycroft 9 Sherlock’s Last Case 9 From the Editor’s Desk Study Group 10 n this last issue of Explorations for 2006 delivered at our annual dinner, joining I we recap our recent annual meeting and frequent contributors Mike Eckman and dinner, notable for a changing of the guard Bob Brusic as well as Study Group reviewer as Julie McKuras stepped down after an Charles Clifford. Phil Bergem continues his energetic nine years as president of the Nor- Internet Explorations, and we look forward wegian Explorers. We are sure that our new to an upcoming performance of a Sher- president, Gary Thaden, will ably carry on lockian play. in the tradition of Julie and all our past Letters to the editor or other submis- leaders, including our founder and Siger- sions for Explorations are always welcome. son, the late E.W. “Mac” McDiarmid. We Please email items in Word or plain text also note travels by Explorers to two recent format to [email protected] conferences, both of which featured speak- ers from the ranks of the Explorers. We John Bergquist, BSI welcome Ray Riethmeier as a contributor to Editor, Explorations the newsletter by printing his fine toast Page 2 EXPLORATIONS Issue #53 From the (Incoming) President Internet Explorations . -

Sherlock's Relationships in the Twenty-First Century

1 Sherlock's Relationships in the Twenty-First Century BA Thesis Stijn Koster 3653099 Gageldijk 84b 3566 MG Utrecht English Language and Culture dr. Roselinde Supheert 29 June 2014 2 Table of Contents Introduction 3 Chapter 1: Adaptations 4 Chapter 2: Who is Sherlock? 6 Chapter 3: The Relationship Between Holmes and Watson 10 Chapter 4: Sherlock and the Others 15 4.1 Mycroft Holmes 16 4.2 Jim Moriarty 18 4.3 Gregory Lestrade / Scotland Yard 20 4.4 Mary Morstan 21 4.5 Irene Adler 23 4.6 Molly Hooper 23 4.7 A Conclusion to the Characters 25 Conclusion 26 Bibliography 27 3 Introduction There are very few people who have never heard of Sherlock Holmes. That is not because everyone has read Arthur Conan Doyle's stories about this famous character. Ever since the stories were first published in 1887 they have been adapted into screen films and television series. During these 100 years the character has also transformed. Newer adaptations have also been inspired by previous adaptations, which changes the Holmes that was first created by Conan Doyle into a character that the everyone who adapts him contributes to. Film adaptations are a filmmaker's interpretations of stories and characters. In recent years several Sherlock Holmes adaptations have been created. Many alterations regarding the original stories by Doyle have been made to please the contemporary audience. Due to limited time and space, this thesis shall focus mainly on the BBC series Sherlock created by Mark Gatiss and Steven Moffat, which first aired in 2010. Gatiss and Moffat have analysed the characters and stories thoroughly; they have then deconstructed them en reassembled them in twenty-first century England. -

To Look for a Society in Your Area

ZSOC-GEO.TXT ACTIVE SHERLOCKIAN SOCIETIES (GEOGRAPHICAL) (AS OF JULY 17, 2017): Baker Street Vienna Silvia Groniewicz AT Vienna Anton-Baumgartnerstrasse 44/C5/1/1 1230 Vienna AUSTRIA The Sydney Passengers Bill Barnes AU NS Sydney 19 Malvern Avenue Manly, N.S.W. 2095 AUSTRALIA The Sherlock Holmes Society of South Australia Mark Chellew AU SA Adelaide P.O. Box 85 Daw Park, SA 5041 AUSTRALIA The Sherlock Holmes Society of Melbourne Michael Duke AU VI Melbourne 3 Gillies Street Hampton, Vic. 3188 AUSTRALIA The Sherlock Holmes Society of Western Australia Fred Rutter AU WA Perth 49 Cedar Way Forrestfield, WA 6058 AUSTRALIA Le peloton des cyclistes solitaires Cedric C. Goffinet BE Brussels Rue de Levallois-Perret 46 B-1080 Bruxelles The 221Bees Ivo Dekoning BE Lummen Goeslaerstraat 45 3560 Lummen BELGIUM The Isadora Klein Amateur Mendicant Society Carlos Orsi Martinho BR Jundiai r. Zacarias de Goes, 404, ap. 92 Jundiai-SP 13201-800 BRAZIL The Singular Society of the Baker Street Dozen Charles Prepolec Page 1 ZSOC-GEO.TXT CA AB Calgary 101 Royal Bay NW Calgary, AB T3G 5J6 CANADA The Wisteria Lodgers of Edmonton Constantine Kaoukakis CA AB Edmondon 9705 163rd Street NW Edmonton, AB T5P 3N1 CANADA The Stormy Petrels of British Columbia Krista Lee Munro CA BC Vancouver e-mail: [email protected] CANADA The Great Herd of Bisons of the Fertile Plains Ihor Mayba CA MB Winnipeg 6 Melness Bay Winnipeg, MB R2K 2T5 CANADA The Halifax Spence Munros Mark J. Alberstat CA NS Halifax 46 Kingston Crescent Dartmouth, NS B3A 2M2 CANADA The Main Street Irregulars Trevor S. -

The Evolution of Sherlock Holmes: Adapting Character Across Time

The Evolution of Sherlock Holmes: Adapting Character Across Time and Text Ashley D. Polasek Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY awarded by De Montfort University December 2014 Faculty of Art, Design, and Humanities De Montfort University Table of Contents Abstract ........................................................................................................................... iv Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................... v INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 1 Theorising Character and Modern Mythology ............................................................ 1 ‘The Scarlet Thread’: Unraveling a Tangled Character ...........................................................1 ‘You Know My Methods’: Focus and Justification ..................................................................24 ‘Good Old Index’: A Review of Relevant Scholarship .............................................................29 ‘Such Individuals Exist Outside of Stories’: Constructing Modern Mythology .......................45 CHAPTER ONE: MECHANISMS OF EVOLUTION ............................................. 62 Performing Inheritance, Environment, and Mutation .............................................. 62 Introduction..............................................................................................................................62 -

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle – His Stonyhurst Years

Dear George Your email to Lucy Hammerton has been forwarded to me. As you will already know, Arthur Conan Doyle attended Stonyhurst between 1868 and 1875, spending the first two years at the nearby prep school,at Hodder Place and the remaining five at the College. Unfortunately, he left before the only sustained official journal – The Stonyhurst Magazine - was initiated. Before that there were a number of unofficial (i.e. pupil-led) publications. These were handwritten and therefore diminutive in size and limited to one or two copies and very few issues. The only one dating from ACD’s time was called The Wasp. He actually played a part in its production but unfortunately, to the best of my knowledge, no known copies have survived. I am attaching a piece I have prepared on ACD at Stonyhurst, which includes a little more detail of this. It is perhaps a little curious that ACD should have contributed cartoons when another of the editorial team was Bernard Partridge (later Sir Bernard Partridge), who went on to become a lifelong professional artist, most famous for his cartoons, especially in Punch. He became Chief Cartoonist for this periodical in 1910 and continued to produce cartoons for Punch until shortly before his death in 1945. The very first Chief Cartoonist for Punch had been Richard Doyle, ACD’s uncle Dicky, until 1850, when he was replaced by John Tenniel. Both Tenniel and Doyle were later knighted. You are most welcome to use any of the information in the attached document, as long as it is appropriately accredited, please, in the bibliography. -

Exsherlockholmesthebakerstre

WRITTEN BY ERIC COBLE ADAPTED FROM THE GRAPHIC NOVELS BY TONY LEE AND DAN BOULTWOOD © Dramatic Publishing Company Drama/Comedy. Adapted by Eric Coble. From the graphic novels by Tony Lee and Dan Boultwood. Cast: 5 to 10m., 5 to 10w., up to 10 either gender. Sherlock Holmes is missing, and the streets of London are awash with crime. Who will save the day? The Baker Street Irregulars—a gang of street kids hired by Sherlock himself to help solve cases. Now they must band together to prove not only that Sherlock is not dead but also to find the mayor’s missing daughter, untangle a murder mystery from their own past, and face the masked criminal mastermind behind it all—a bandit who just may be the brilliant evil Moriarty, the man who killed Sherlock himself! Can a group of orphans, pickpockets, inventors and artists rescue the people of London? The game is afoot! Unit set. Approximate running time: 80 minutes. Code: S2E. “A reminder anyone can rise above their backgrounds and past, especially when someone else respectable also respects and trusts them.” —www.broadwayworld.com “A classic detective story with villains, cops, mistaken identities, subterfuge, heroic acts, dangerous situations, budding love stories and twists and turns galore.” —www.onmilwaukee.com Cover design: Cristian Pacheco. ISBN: 978-1-61959-056-4 Dramatic Publishing Your Source for Plays and Musicals Since 1885 311 Washington Street Woodstock, IL 60098 www.dramaticpublishing.com 800-448-7469 © Dramatic Publishing Company Sherlock Holmes: The Baker Street Irregulars By ERIC COBLE Based on the graphic novel series by TONY LEE and DAN BOULTWOOD Dramatic Publishing Company Woodstock, Illinois • Australia • New Zealand • South Africa © Dramatic Publishing Company *** NOTICE *** The amateur and stock acting rights to this work are controlled exclusively by THE DRAMATIC PUBLISHING COMPANY, INC., without whose permission in writing no performance of it may be given. -

Univerza V Mariboru

UNIVERZA V MARIBORU FILOZOFSKA FAKULTETA ODDELEK ZA ANGLISTIKO IN AMERIKANISTIKO DIPLOMSKO DELO STANKA RADOVIĆ MARIBOR, 2013 UNIVERZA V MARIBORU FILOZOFSKA FAKULTETA ODDELEK ZA ANGLISTIKO IN AMERIKANISTIKO Stanka Radović PRIMERJALNA ANALIZA FILMA “IGRA SENC” IN KNJIGE “BASKERVILLSKI PES” Diplomsko delo Mentor: red. prof. dr. Victor Kennedy MARIBOR, 2013 UNIVERSITY OF MARIBOR FACULTY OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AND AMERICAN STUDIES Stanka Radović A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF “A GAME OF SHADOWS” WITH THE BOOK “THE HOUND OF THE BASKERSVILLES” Diplomsko delo MENTOR: red. prof. dr. Victor Kennedy MARIBOR, 2013 I would like to thank my mentor, dr. Victor Kennedy for his support, help and expert advice on my diploma. I would like to thank my parents for their support, for all the sacrifices in their lives and for believing in me and being there for me all the time. POVZETEK RADOVIĆ, S.: Primerjalna analiza filma in knjige: A game of Shadow in The Hound of the Baskervilles. Diplomsko delo, Univerza v Mariboru, Filozofska fakulteta, Oddelek za anglistiko in amerikanistiko, 2013. V diplomski nalogi z naslovom Primerjalna analiza filma Igra senc in knjige Baskervillski pes je govora o deduktivnem načinu razmišljanja in o njegovem opazovanju, ki ga je v delih uporabljal Sherlock Holmes. Obravnavano je tudi vprašanje, zakaj je Sherlock Holmes še vedno tako priljubljen. Beseda teče tudi o življenju v viktorijanski Angliji. Osrednja tema diplomskega dela je primerjava filma in knjige. Predstavljene so vse podobnosti in razlike obeh del. Ključne besede: Sherlock Holmes, deduktivni način razmišljanja in opazovanja, viktorijanska Anglija ABSTRACT RADOVIĆ, S.: A Comparative analysis of “A Game of Shadow” with the book “The Hound of the Baskervilles”. -

William S. Baring-Gould Was a Time Executive Whose Contributions to the Literary World (And Especially to Sherlockians) Are Manifest

Honorary Member, Emeritus photo courtesy of Bill Vande Water William Stuart Baring-Gould 1913-1967 William S. Baring-Gould was a Time executive whose contributions to the literary world (and especially to Sherlockians) are manifest. Mr. Baring-Gould was a descendent of the well-known author and archivist Reverend Sabine Baring-Gould (1834-1924) who was a featured character in Laurie King's book The Moor. He was the author of numerous important Sherlockian works including, Sherlock Holmes of Baker Street, The Chronological Holmes and the famous The Annotated Sherlock Holmes. The Annotated Sherlock Holmes is considered by many Sherlockians as his crowning achievement and is a must in every Sherlock Holmes Collection. He authored other works, including The Lure of the Limerick: An Uninhibited History, Nero Wolfe of West Thirty-fifth Street (a work about the detective whom some speculate is the "son" of Sherlock Holmes) and collaborated with his wife, Ceil, onThe Annotated Mother Goose, Nursery Rhymes Old and New. All of these works are important volumes in their respective literary worlds. Mr. Baring-Gould was BSI and invested as "The Gloria Scott". Julian Wolfe said at his passing: "In the true Irregular tradition, and in accordance with the precepts of Christopher Morley, he was always ready to encourage young Sherlockians, many of whom owe much to his valuable asistance." Sherlockian.Net: William S. Baring-Gould Bill Baring-Gould, 1913-1967 W. S. Baring-Gould was an executive of Time Inc. and a distinguished though modest Sherlockian (invested in the Baker Street Irregulars as "The Gloria Scott", 1952). -

I Am an Omnivorous Reader 5975W

“I AM AN OMNIVOROUS READER” Book reviews by CATHERINE COOKE, ALISTAIR DUNCAN, GORDON DYMOWSKI, MATTHEW J ELLIOTT, MARK MOWER, SARAH OBERMULLER-BENNETT, VALERIE SCHREINER, JOHN SHEPPARD, JEAN UPTON, NICHOLAS UTECHIN and ROGER JOHNSON This August and Scholarly Body: The Society at Blaze . If it had a name it’s in the book! 70 edited by Nicholas Utechin; design and layout by For each character we are given the name, story, Heather Owen. The Sherlock Holmes Society of sex, and whether they are alive or dead in the Canon. London , 2021. 116pp. £11.00 (pbk) In addition, depending on the importance of the They say that when drowning, one’s life flashes character, are details which can range from physical before one’s eyes. Reading this book is rather like that appearance to occupation and, if relevant, what — only somewhat drier! While I do not go back to the Holmes deduced about them. Holmes himself has a Society’s foundation in 1951, I do go back over half predictably long entry, whereas, for instance, Captain the Society’s existence and have had much to do with Ferguson (“The Three Gables”) is concisely the 1951 Festival of Britain in Westminster Libraries. described: “A retired sea captain who owned the This is a fitting record, a highly enjoyable read and an house before Mrs Maberley. Holmes asked if there invaluable reference book. There are lists of the was anything about remarkable about him, and if he Presidents, Chairmen and Honorary Members and a had buried something. Mrs Maberley answered in the useful list of all the Society’s publications, so you can negative.” check for any gaps on your shelves that need filling. -

Ebsj-Sample.Pdf

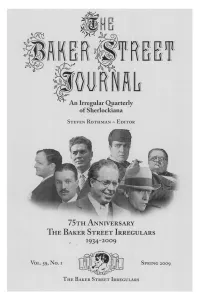

G E P4 \ e # An Irregular Quarterly of Sherlockiana STEVEN ROTHMAN EDITOR 75TH ANNIVERSARY THE BAKER STREET IRREGULARS 1934-2009 - "I's- ti 0 VOL. 59, No I SPRING 2009 ;a. THE BAKER STREET IRREGULARS Cover Illustration Key In honor of the 75th Anniversary of The Baker Street Irregulars our cover illustration features a montage of personalities who attended the very first dinner in 1934. 1. Christopher Morley; 2. H.W. Bell; 3. Vincent Starrett; 4. Basil Davenport; 5. Gene Tunney; 6. William Gillette; 7. Alexander Woollcott Volume 59 Number 1 Spring 2009 An Irregular Quarterly of Sherlockiana Founded by EDGAR W. SMITH Continued by JULIAN WOLFF, M.D. "Si monumentum quaeris, circumspice" Editor: STEVEN ROTHMAN Published by THE BAKER STREET IRREGULARS Copyright 2009 by THE BAKER STREET IRREGULARS All rights reserved LC 49-17066 ISSN 0005-4070 The appearance of the code following this statement indicates the copyright owner's consent that copies of articles in this journal may be made for personal or internal use, or for the personal internal use of specific clients. The consent is given on the condition, however, that the copier pay the stated per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, Inc., 21 Congress Street, Salem, MA 01970, for copying beyond that permitted by law including sections 107 and 109 of the United States Copyright Act. This consent does not extend to other kinds of copying, such as copying for general distribution, for advertising or promotional purposes, for creating new collective works, or for resale. Users should employ the following code when reporting copying from this issue to the Copyright Clearance Center: 0005 4070/91/$1.00 Articles in the JOURNAL are regularly indexed in Humanities International Complete (HIC).