WHEN TRANSFORMATION FAILS Twelve Case Studies in the Automobile Industry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chrysler, Dodge, Plymouth Brakes

CHRYSLER, DODGE, PLYMOUTH BRAKES After Ford started build- mouth, the medium ing horseless carriages, priced DeSoto, and the many other people saw high priced Chrysler. their potential and they Soon after that, Chrysler started building similar purchased the Dodge vehicles. Engineers and Brothers Automobile and stylists formed many of Truck Company, and the the early companies so Dodge also became a they were building nice medium priced car just cars, but the companies below DeSoto. All of the didn’t have a coherent 1935 Chrysler Airflow Chrysler truck offerings business plan. Some of the early companies were marketed under the Dodge name and that has- merged together for strength and that didn’t nec- n’t changed. General Motors used the hierarchy essarily help their bottom line. One of the early principal and it was working well for the Company, companies that started having financial problems so Chrysler borrowed the idea. was the Maxwell-Chalmers Company. Walter P. Chrysler was asked to reorganize the company Chrysler ran into a situation in the early ‘30s when and make it competitive. Chrysler did that with the their advanced engineering and styling created an Willys brand and the company became competi- unexpected problem for the Company. Automotive tive and lasted as a car company until the ‘50s. stylists in the late-’20s were using aerodynamics to The company is still around today as a Jeep man- make the early cars less wind resistant and more ufacturer that is currently owned by Chrysler. On fuel-efficient. Chrysler started designing a new car June 6, 1925, the Maxwell-Chalmers Company with that idea in mind that was very smooth for the was reorganized into the Chrysler Company and time period and in 1934 they marketed the car as the former name was dropped and the new car the Chrysler Airflow. -

Amcrc Monthly News & Ad Release

SEPTEMBER 2018 the carpet too. Color is black, 2-piece, not factory original, AMCRC CLASSIFIED AD RELEASE but a good quality replacement put in some years ago. No shipping - pick-up only. #6122 Pat Foster in CT. 203- Specializing in AMC cars / parts 877-6717 / [email protected] (10) ________________________________ (1) 4-blade fan, part #3224499, like new - $5 (2) license plate lamp lens, fits ‘64-‘69 American, good used - $10 (3) front drum & hub assembly, 9” x 2-1/2", fits 58-72 6 SEND ALL ADS TO: cyl, good used - $5 (4) Hood hinge, fits ‘64-‘69 American, Brian M Yacino driver side, like new - $35 (5) complete AM radio from ‘68 American, NOT working - $5 (6) master cylinder from ‘68 Classified Ads (specific items for specific prices) are for AMC cars American with drum brakes, good used - $5. #6446 Scott / parts. All ads run for 3 months, and must be renewed to continue. Watson, 903 Moravian Way, Pittsburgh, PA 15212. 412- Each ad ends with a number or characters in parentheses. The first 737-8576 / [email protected] (09) is the final month that the ad will run. A ‘P’ means that a non-member ________________________________ paid for the ad. A ‘W’ means that the ad is also posted on the AMCRC website with photos. This publication is for classified ads containing a specific product or service for a specific price. General, unchanging CARS FOR PARTS or RESTORATION ads for services or parts will be transferred to our Parts Source Guide, Parts car for sale: 1959 Rambler Ambassador Custom which will be posted in our Members’ Area. -

Ministry Nod for Three Free Trade Zones

ISO 9001:2008 CERTIFIED NEWSPAPER Thursday 29 May 2014 30 Rajab 1435 - Volume 19 Number 6080 Price: QR2 LNG supply to face competition Business | 17 1 4 DAYS TO GO www.thepeninsulaqatar.com [email protected] | [email protected] Editorial: 4455 7741 | Advertising: 4455 7837 / 4455 7780 Father Emir, Sheikha Moza attend graduation Al Sisi heads Ministry nod for big win in early count CAIRO: Former Egyptian for three free army chief Abdel Fattah Al Sisi was on course for a sweeping vic- tory in the country’s presidential election yesterday, according to early provisional results. Sisi’s trade zones campaign said their man had captured 93.4 percent with 2,000 polling stations counted, while Plan for new livestock market judicial sources said he had 89 percent with 3,000 polling sta- DOHA: The Ministry of Municipality and Urban Planning, tions counted. His only rival, Municipality and Urban Noora Al Suwaidi. veteran leftist Hamdeen Sabahi, Planning has eventually She told in a presenta- was on 2.9 percent according to approved plans to establish the tion at the Central Municipal the Sisi campaign, while the judi- three free trade zones (FTZs) Council (CMC) on Qatar’s urban cial sources put Sabahi on 5 per- that are being talked about for a Masterplan, that the FTZ plans cent, with the rest of the ballots long time. However, a new loca- had been approved by the minis- deemed void. tion is being discussed for one of try. Two massive industrial zones Turnout was 44.4 percent of the FTZs which was originally were being planned for setting up Egypt’s 54 million voters, accord- planned to be set up south of warehousing facilities. -

Modern Moparmopar ER CAR SL C Y L R U H B

HRYSLE R C O C A F R S C O L U U T B H A U A STR ALI Modern Mopar ER CAR SL C Y L R U H B C O F A I S L O A GHFHPEHURPDUFKR U R TH AUST President Iain Carlin General monthly meetings are held on the FIRST Tuesday of every month at: Vice President Hugh Mortimer The West Adelaide Football Club, 57 Milner Rd, Richmond. Secretary Di Hastwell Treasurer Greg Helbig Events Coordinator Damian Tripodi ACF Coordinator Jason Rowley Regular - $40.00 per year (& quarterly magazine) Events Organisers John Leach Historic Registration - $50 per year (& quarterly magazine) Chris Taylor Historic Registrar Stuart Croser Inspectors North John Eckermann Jason Rowley South Chris Hastwell Charles Lee Central Rob McBride Dave Hocking Sponsorship & Marketing Evan Lloyd Club Library Iain Carlin Editorial / Design Dave Heinrich Webmasters Iain Carlin Dave Heinrich Photography Mary Heath Iain Carlin Lesley Little Ingrid Matschke Damian Tripodi Paris Charles John Antinow Charles Lee Mandy Walsh Contributors Iain Carlin Hugh Mortimer Lesley Little Rick Saxon John Antinow Guy Oakes Stuart Croser Damian Tripodi Source Wikipedia Allpar Hot Rod Car Advice Car & Driver FourWheeler.com DISCLAIMER CarWeekly.co.uk Chrysler, Jeep®, Dodge and Mopar are registered trademarks of FCA LLC and are used with permission by the Chrysler Car Club of South Australia. Enquiries Torqueback is not a commercial publication and is only published in good faith as a newsletter for a not-for-proÀt organisation. Club Mobile The mention of companies, products or services, and the inclusion of advertisements in this magazine does not immediately 0412 426 360 imply any automatic endorsement by the Chrysler Car Club of South Australia or its editorial team. -

Brakes, Rotating Machines, and Spark Plugs Automotive Aftermarket North America New Product Communication | July 2016

Brakes, Rotating Machines, and Spark Plugs Automotive Aftermarket North America New Product Communication | July 2016 Bosch QuietCast™ Disc Brake Pads Product Category Overview 1 Part Number 24K Units in Operation Robert Bosch LLC, the leading manufacturer and supplier Hardware kit included on select applications to both the original equipment manufacturer (OEM) and Syntectic lubricant included with all application the aftermarket, announces the addition of 10 new and Late model European vehicle 36 relaunched part numbers. The featured product lines for July are brakes, rotating machines, and spark plugs. Bosch Brakes Bosch Blue Disc Brake Pads Three new brake pads sets are being added to the 2 Part Numbers 6K Units in Operation Bosch Brake portfolio. Two of these new part numbers are Bosch Blue Brake pads sets. These Bosch Blue OE-style, multi-layer shims for superior noise dampening Brake pads are for Freightliner and Mercedes-Benz Towel-wrapped on selected applications for added protection and value Late model Domestic and European vehicle Sprinters. One new Bosch QuietCast Brake pads set is being added to cover late model European vehicle. Bosch Rotating Machines Bosch Rotating Machines Bosch releases 7 additions to the Bosch Rotating 7 Part Numbers 3.9 Million Vehicles in Operation Machine line covering 3.9 million vehicles in the US. These part number additions are for Asian and Domestic Late model Asian and Domestic coverage vehicles that may no longer be serviced under warranty, Meet or exceed manufacturer recommendations but are prime candidates for serviceability in the IAM (Independent Aftermarket). New coverage includes Buick, Chevrolet, Ford, Hyundai, Kia, Nissan Pontiac, and Toyota. -

2018 Aaca Grand National Entry List

Annual Grand National Vehicles by Class May 31-June 2, 2018 Greensburg, PA Class # Award Sought Vehicle # Name Member # Make Year BodyStyle 02 Sr Grand Nat'l 20237 Hutton, Norman 426218 Sears J 1908 Runabout 03B Repeat Sr Grand Nat'l 22472 Green, Valerie 337715 Citicar Electric 1976 Coupe 04A 1st Grand Nat'l 22839 Brock, Jeff 004972 American Austin 1931 Roadster 04B 1st Grand Nat'l 20657 Young, Barbara 976466 Nash Metropolitan 1957 Coupe Sr Grand Nat'l 30629 McMillen, Randy E 566164 BMW Isetta 1957 Cabriolet Sr Grand Nat'l 30745 Wotkowski, Ray 969572 BMW Isetta 1958 Coupe Repeat Sr Grand Nat'l 28132 Covitz, Charles 186317 Citroen 2CV 1972 Roadster 04C 1st Grand Nat'l 30041 Hedeen, John K 200206 Volkswagen Type 2 1963 Truck 1st Grand Nat'l 32388 Reischman, Richard 600265 Volkswagen Karmann 1957 Coupe Ghia Sr Grand Nat'l 15572 Kuhnash, Greg 220064 Volkswagen 113 1956 Sedan Sr Grand Nat'l 24667 Coach, Robert G 200185 Volkswagen Beetle 1965 Sedan Repeat Sr Grand Nat'l 18363 Russo, Charles T 800449 Volkswagen Rabbit 1980 Coupe 05A Sr Grand Nat'l 29004 Taylor, Richard 870880 Harley-Davidson C 1910 Motorcycle Repeat Sr Grand Nat'l 20142 Lilly, Melvin E 524898 Harley-Davidson J 1917 Motorcycle 05C 1st Grand Nat'l 31183 Swan II, Marcus C 998618 Hercules K-125 1957 Motorcycle 05D Sr Grand Nat'l 27829 Hedeen, John K 200206 Rupp L-80 1973 Motorbike Sr Grand Nat'l 29409 Laughman, Wayne K 507140 Whizzer Pacemaker 1948 Motorbike Repeat Sr Grand Nat'l 26996 Laughman, Eugene L 507106 Whizzer Cycle Truck 1949 Motorbike 05G 1st Grand Nat'l 31385 Rand, Glenn -

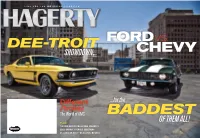

Showdown ... of Them All!

FUEL FOR THE MOTORING LIFESTYLE Dee-troit Ford vs. showdown ... CHevy Fall 2011 $4.95 U.S.a. | Canada Different ... for the Strokes The World of AMC baddest Plus: of them all! THE ODD ART OF COLLECTING CONCEPTS COOL GARAGE STORAGE SOLUTIONS ST. LOUIS OR BUST—IN A LOTUS, NO LESS a word from mckeel FordFord vs.vs. Chevy Chevy in the Driver’s seat editoriAl stAFF Executive Publisher McKEEL Hagerty Publisher RoB SASS Associate Publisher Jonathan A. Stein Senior Publishing Advisor Greg Stropes Executive Editor JERRy Burton Managing Editor nAdInE SCodELLARo Art director/designer Todd Kraemer Copy Editor SHEILA WALSH dETTLoFF Art Production Manager JoE FERRARo Although McKeel Creative director LAURA RoGERS hagerty spends as Editorial director dAn GRAnTHAM much time as possible in the driver’s seat, he Publishing stAFF director of Publishing Angelo ACoRd found time to sit on a Publication Manager Danielle PoissanT panel of notable auto Production Manager Lynn Sarosik MAGES editors and writers y I Ad Sales Coordinator KIM PoWERS to make his picks in ETT our Ford vs. Chevy Contributors Carl Bomstead, BoB Butz, WAynE on, G showdown. rt CarinI, KEn GRoss, DavE KInnEy, Stefan Lombard, jeff peek, JoHn L. Stein n Mo TEPHE Advertising stAFF S director of Ad Sales East Coast Sales office ToM Krempel, 586-558-4502 [email protected] Central/West Coast Sales office Lisa Kollander, 952-974-3880 Fun with cars [email protected] Anyone who’s read at least one issue of Hagerty magazine realizes that we subscribe to the notion that the old car hobby is supposed to be fun — fun in the sense that we enjoy using our cars from time to time and that we have a good time poking fun both at ourselves and the foibles of our beloved old cars. -

Sc7038 Control Arm 39021716 Buick/Chevrolet Buick Verano /Flagship Cruze

SC7038 CONTROL ARM 39021716 BUICK/CHEVROLET BUICK VERANO /FLAGSHIP CRUZE SC7039 CONTROL ARM 9063362 BUICK/CHEVROLET CHEVROLET CLASSICS CRUZE 15‐ SC7040 CONTROL ARM 9063363 BUICK/CHEVROLET CHEVROLET CLASSICS CRUZE 15‐ SC7041 CONTROL ARM BUICK/CHEVROLET GL8 17 SC7042 CONTROL ARM BUICK/CHEVROLET GL8 17 SC7043 CONTROL ARM 26252503 BUICK/CHEVROLET GL6 SC7044 CONTROL ARM 26252504 BUICK/CHEVROLET GL6 SC7045 CONTROL ARM 22730775 BUICK/CHEVROLET 16NEW LACROSSE /16MALIBU XL SC7046 CONTROL ARM 22730776 BUICK/CHEVROLET 16NEW LACROSSE /16MALIBU XL SC7047 CONTROL ARM 22924235 BUICK/CHEVROLET 16NEW LACROSSE /16MALIBU XL SC7048 CONTROL ARM 22924236 BUICK/CHEVROLET 16NEW LACROSSE /16MALIBU XL SC7049 CONTROL ARM 26249755 BUICK 18 EXCELLE GT SC7050 CONTROL ARM 26249756 BUICK 18 EXCELLE GT SC7051 CONTROL ARM 88955493 CADILLAC SRX 10‐ SC7052 CONTROL ARM 88955494 CADILLAC SRX 10‐ SC7053SATISFACTION CONTROL ARM 22833483 CADILLAC SRX 10‐ SC7054 CONTROL ARM 22833484 CADILLAC SRX 10‐ SC7055 CONTROL ARMWARRANTY 22905357 CADILLAC XTS SC7056 CONTROL ARM 22905358 CADILLAC XTS SC7057 CONTROL ARM 20759935 CADILLAC ATS/ATS L/NEW CTS 127 SC7058 CONTROL ARM 20759936 CADILLAC ATS/ATS L/NEW CTS SC7059 CONTROL ARM 20759980 CADILLAC ATS/ATS L/NEW CTS SC7060 CONTROL ARM 20759981 CADILLAC ATS/ATS L/NEW CTS SC7061 CONTROL ARM 25752929 CADILLAC CTS 05‐07 SC7062 CONTROL ARM 25752930 CADILLAC CTS 05‐07 SC7063 CONTROL ARM 25758282 CADILLAC CTS 05‐07 SC7064 CONTROL ARM 25758283 CADILLAC CTS 05‐07 SC7065 CONTROL ARM 15219467 CADILLAC CTS 08‐13 SC7066 CONTROL ARM 15219468 CADILLAC CTS -

AMC Straight-6 Engine 1 AMC Straight-6 Engine

AMC straight-6 engine 1 AMC straight-6 engine The American Motors Corporation (AMC) straight-6 family of engines was used in AMC passenger cars and Jeep vehicles from 1964 through 2006. 195.6 American Motors' first straight-six engine was the 195.6 cu in (unknown operator: u'strong' L). It was produced from 1958 through 1965 in both overhead valve (OHV) and flathead (L-head) side-valve versions. Sometimes referred to as the 196 engine, this engine was originally designed by Nash in the 1930s as a flathead, and redesigned as an OHV engine in 1956. The flathead version was discontinued for 1956–1957, but reemerged in 1958 as the economy engine for the "new" Rambler American. When the engine was changed to an OHV configuration the water pump was moved from the left side of the engine (driven by a shaft extending from the back of the generator) to the front above the timing chain. When the flathead model was reintroduced it also received the new water pump. Equipped with such high quality parts as forged crankshafts and connecting rods, these engines earned a reputation for remarkable durability. The flathead, however, was prone to the typical flathead problem of overheating under sustained heavy load. This was from the hot exhaust traveling through the cylinder block to the exhaust manifold. American Motors introduced a die-cast aluminum block version of the OHV 195.6 cu in (unknown operator: u'strong' L) engine in 1961. It was produced through 1964. This engine used cast-iron cylinder liners and a cast-iron head. -

TEQ® Correct Professional Brake Pads

Most Popular Numbers ‐ TEQ® Correct Professional Brake Pads Line Rank Part # Vehicle Applications Code •Cadillac - Escalade (2002-2006) Front, Escalade ESV (2003-2006) Front, Escalade EXT (2002-2006) Front•Chevrolet - Astro (2003-2005) Front, Avalanche 1500 (2002-2006) Front, Avalanche 2500 (2002-2006) Rear, Express Vans (2003-2008) Front, Silverado Pickups (1999-2007) Front, Silverado Pickups (1999-2010) Rear, Silverado Pickups V8 5.3 (2005-2007) Front, Suburbans (2000-2006) Front, Suburbans (2000-2013) Rear, Tahoe (2000-2006) Front•GMC - C-Series Pickups 1 PDP PXD785H (2000) Rear, C/K Series Pickups (2000) Rear, Safari (2003-2005) Front, Savana Vans (2003-2008) Front, Sierra Pickups (1999-2007) Front, Sierra Pickups (1999-2010) Rear, Sierra Pickups V8 6.6 (2001-2002) Front, Sierra Pickups V8 8.1 (2002) Front, Sierra Pickups V8 6.0 (2005) Front, Sierra Pickups V8 6.0 (2005) Rear, Sierra Pickups V8 6.6 (2005) Rear, Yukons (2000-2006) Front, Yukons (2000-2013) Rear•Hummer - H2 (2003-2009) Rear •Cadillac - Escalade (2008-2014) Front, Escalade ESV (2008-2014) Front, Escalade EXT (2008-2013) Front, XTS (2013) Front•Chevrolet - Avalanche (2008-2013) Front, Express Vans (2009-2014) Front, Silverado Pickups (2005-2013) Front, Silverado Pickups V6 4.3 (2005-2007) Front, Silverado Pickups V8 4.8 (2005-2007) Front, Silverado Pickups V8 5.3 (2005- 2 PDP PXD1363H 2007) Front, Silverado Pickups V8 6.0 (2007) Front, Suburbans (2007-2014) Front, Tahoe (2008-2014) Front, Tahoe V8 4.8 (2008) Front, Tahoe V8 5.3 (2008) Front•GMC - Savana Vans (2009-2013) -

Collection of Misfits

Volume 18 Issue 1 January 1, 2018 Collection of Misfits Richard Koop — What was he thinking! I started collecting cars in October 1980 and my first purchase was a ‘56 Mark II. I was fortunate enough to find a DSO (Dealer Special Order) car that had a unique all leather one- color roof liner, door panels and seats. It was originally ordered by a farmer and his wife in Iowa thru the Stivers Lincoln dealership in Des Moines, Iowa. The wife wanted a special color red leather to match the lipstick she used. Because of the special treatment, Lincoln wanted to show their affluent customers (Think Black Label Program-not Hormel bacon- today) they would do these special requests. A tube of lipstick was sent to Ford, and the Welcome to the leathers (Bridge of Weir) were dyed to match the lipstick. I remember taking the MK II to a Northstar News, the meet in Delroy, Ohio not much after I bought the car. I was trying to learn all I could about monthly publication of these cars and I met Jim Roll; who was probably one of the most knowledgeable leather and the Northstar Region upholstery guys I have ever met. He stopped by and asked what my plans were for the leather interior. It was showing some fading and a few minor cracks in the leather so I said I would of the Lincoln and probably re-dye and replace some of the leather sections. He looked at me and said …. Well, Continental Owners what he said I shouldn’t repeat, but he “expressed” displeasure with my plans. -

Sustainability Report 2008/9

Report Home Contact Downloads GRI Index UNGC Index Site Map Glossary Economy During 2008 we: Made progress on our restructuring plan Modified our UAW agreement Continued to improve vehicle quality ECONOMY Ford Motor Company has a broad range of economic impacts. Our success as a company directly RELATED LINKS Progress affects millions of employees, dealers, investors and suppliers. We also have indirect economic impacts In This Report: Financial Recovery Plan on the hundreds of communities in which we operate worldwide. Economic Impacts of the Automotive Industry Investor Ratings and To sustain our Company, meet our responsibilities and contribute to tackling global sustainability Feedback issues, we are continuing to implement our restructuring plan, aligning all of our global operations to Our Value Chain and Its Impacts Ford Motor Credit Company focus on four key priorities: Materiality Analysis Data Aggressively restructure to operate profitably at the current demand and changing model mix Case Studies Accelerate the development of new products our customers want and value Finance our plan and improve our balance sheet Print report Work together effectively as one team Download files This section first briefly discusses the current business environment, highlights of our recent progress and our materiality analysis. The bulk of the section then addresses our financial recovery plan, including our progress in implementing the above four priorities. (Note that the risks and competitive factors discussed in our Annual Report on Form 10-K may affect the implementation of these plans). The section also includes information on investor feedback and ratings and Ford Motor Credit Company, as well as two case studies: one on the automotive industry's impact on the U.S.