The Burden of Cutaneous and Mucocutaneous Leishmaniasis in Ecuador

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transportation and Commercial Development in Pichincha Province

TRANSPORTATION AND COMMERCIAL DEVELOPMENT IN PICHINCHA PROVINCE, ECUADOR by Bruce E. Ratford Submitled in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Pachelar of Arts ( Honours ) to the Departmant of Geograp!1y, McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario, Canada. - iii PREFACE This thesis is based on data collected during lhree months cf field work in Pichincha Province, Ecuador during the summer of 1970. The researcher was working within the progrcm known os 11 Proyecto Pichincha", a pilot study of the problems of development in a developing country with a view to formulating a model on which might be based recommen- dations on regional improvement 1 and which cou!d help esbblish criteria for a nation-wide study of a similar type. This work is being carried out by the McMaster UniversHy Deportment of Geography and ~he Institute Geogrofico Militar, Quito,Ecuador, under the auspices of the Pan-American !r.stiTute of History and Geography, of which latter group, Dr. Harold A. Wood, McMcster University, is President of the Committee on Regionot (;eogrop"'hy, Thus the area chosen for study and the data co! lee ted were determined by the requirements of the larger project. This study is based on certain aspects of the work carried out and of the information gathered, of ·which only a small part has been used hera. The author wishes to thank Dr. Harold A. Wood for arranging the funding that made it possible to corry out this research, and for potienl·!)'· stJpc:r- vising the preparation of this report. In EcL"ador, the staff of the I.G.M. -

Ecuador Investment Projects

Investment Summit Ecuador 2016 Investment Summit Ecuador 2016 CONTENT 1 Ecuador profile 4 2 Incentives for new investments 6 Benefits of the 8 3 investments contract Incentives for financing and 8 4 investment Public Private Partnerships 9 5 (PPP) Incentives of the Organic Law of 9 6 Solidarity and citizen Co-responsibility 7 Project Catalogue 10 Investment Summit Ecuador 2016 ECUADOR PROFILE Yearly average GDP growth at 4.2%, higher than LATAM at 2.8% ECUADOR: Leading Social Investment in Latin America Central government Social Investment (Percentage of GDP) The largest investment in the history of Ecuador Latin America Ecuador Latin America Ecuador and Caribbean and Caribbean 4 Investment Summit Ecuador 2016 Controlled Inflation Rate, lower than Ecuador Macroeconomic Latin America (2015) Reference Inflation Rate April 2016 14,96 % 10,47 % 7,93 % 4,50 % 4,20 % 4,13 % 3,91 % 2,44 % 1,78 % Strategic and Competitive High Investment in Ecuador versus LATAM as % of GDP (2015) infrastructure USD 329 millions Airports renewed and operated at the national level Airports investment in private public 2007 -2015, which are 2 new airports, 10 refurbished, renovated with air navigation systems optimization at airports nationwide. USD 1,245 millions With public investment in 6 multi-purpose Project of irrigation control and floods. USD 5,900 millions In hydroelectrical plants investment Social - Political until 2015. In 2017 is expected to have 8768 MW Social Development installed capacity. Reducing poverty by 23% (incidence per income), 11% reduction of inequality (Gini index) USD 8,000 millions With a public investment in road network. Human Talent Development 9,200 km of new highways. -

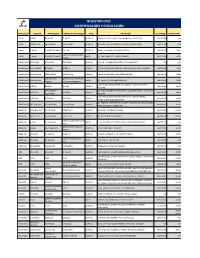

Turnos De Farmacia DICIEMBRE

TURNOS DE FARMACIA Coordinación Zonal 2 Turnos de farmacia DICIEMBRE PICHINCHA RURAL 2020 *RUMIÑAHUI* PROVINCIA Farmacia Ciudad Dirección Teléfono Fecha Inicio Fecha Final 06:00 AM 06:00 AM FARMACIA SANA SANA RUMIÑAHUI - AV GENERAL ENRIQUEZ, 023968500 05 DE DICIEMBRE 12 DE GENERAL ENRÍQUEZ SANGOLQUÍ S/N Y RIO CHINCHIPE. DE 2020 DICIEMBRE DE 2020 FARMACIA SELVA RUMIÑAHUI - CALLE FRANCISCO 0998391431 05 DE DICIEMBRE 12 DE ALEGRE SANGOLQUÍ GUARDERAS, DE 2020 DICIEMBRE DE CONJUNTO: ALCANTARA 2020 4L SELVA ALEGRE 19 DE FARMACIA PLUS RUMIÑAHUI - AV. MARIANA DE JESÚS 0992732231 12 DE DICIEMBRE DICIEMBRE DE SANGOLQUÍ N 644 Y VENEZUELA /022867882 DE 2020 2020 FARMACIA TU RUMIÑAHUI – CALLE GUARDERAS Y 022870671 12 DE DICIEMBRE 19 DE FARMACIA SALUD Y SANGOLQUI JUAN LARREA, N PB Y DE 2020 DICIEMBRE DE BIENESTAR FRANCISCO 2020 GUARDERAS AV GENERAL 022993100 / 26 DE FARMACIA ECONÓMICA RUMIÑAHUI – 19 DE DICIEMBRE RUMIÑAHUI, S/N E ISLA 0985442317 DICIEMBRE DE SAN RAFAEL SAN RAFAEL DE 2020 FLOREANA. 2020 FARMACIA CRUZ AZUL RUMIÑAHUI – AVENIDA GENERAL 022732632 / 26 DE UIO GENERAL ENRIQUEZ SAN RAFAEL ENRÍQUEZ, N/ 3333 E 0992803297 19 DE DICIEMBRE DICIEMBRE DE Y SANTIAGO ISLA SANTIAGO DE 2020 2020 FARMACIAS RUMIÑAHUI - CALLE MERCADO, N 27- 02331061 19 DE DICIEMBRE 26 DE COMUNITARIAS SANGOLQUÍ 35 Y MONTUFAR. DE 2020 DICIEMBRE DE SANGOLQUI 2020 FARMACIA SANTA AV. LOS SHIRIS, N 2-59 RUMIÑAHUI - 022551126 26 DE DICIEMBRE 02 DE ENERO DE MARTHA 280 Y AV. ABDON SANGOLQUÍ DE 2020 2021 CALDERON. FARMACIAS RUMIÑAHUI – AV GENERAL ENRIQUEZ 02 DE ENERO DE ECONOMICAS QUITO 022993100 26 DE DICIEMBRE SAN RAFAEL S/N E ISLA RABIDA. -

Pontificia Universidad Católica Del Ecuador

PONTIFICIA UNIVERSIDAD CATÓLICA DEL ECUADOR ESCUELA DE TRABAJO SOCIAL DISERTACIÓN PREVIA A LA OBTENCIÓN DEL TÍTULO DE “MAGÍSTER EN GESTIÓN DEL DESARROLLO LOCAL Y COMUNITARIO” “ALTERNATIVAS PARA LA REDUCCIÓN SOSTENIBLE DEL ENVEJECIMIENTO DE LA FUERZA PRODUCTIVA EN EL SECTOR AGROPECUARIO DEL CANTÓN PUERTO QUITO, PROVINCIA DE PICHINCHA” ING. LUIS FRANCISCO BRAVO SOLIS DIRECTORA: MGTR. MARÍA CECILIA PÉREZ QUITO - ECUADOR 2016 DECLARACIÓN DE AUTENTICIDAD Yo, Luis Francisco Bravo Solís, declaro en honor a la verdad, que la presente investigación es de total responsabilidad del autor y que se han respetado las diferentes fuentes de información. ____________________________ Luis Francisco Bravo Solís CI: 1712937299 I CERTIFICADO DE AUTORÍA Se autoriza utilizar los contenidos de esta investigación como referencia bibliográfica para fines académicos, por cualquier medio o procedimiento, siempre y cuando se cite como fuente de información al autor de la misma. Octubre de 2016 Nombre: Luis Francisco Bravo Solís Dirección: Portoviejo, Parroquia 12 de marzo, Avenida universitaria y Calle nueva. Email: [email protected] Teléfono: 0982342958 II CERTIFICACIÓN DEL DIRECTOR Mtr. María Cecilia Pérez DIRECTORA DEL PROYECTO DE GRADO CERTIFICA: Haber revisado el presente informe final de investigación, el mismo que se ajusta a las normas vigentes de la Escuela de Gestión Social, de la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador; cumpliendo los requisitos establecidos por la Dirección General Académica; en consecuencia está apta para su presentación y sustentación. -

Sensing TVWS with Open Source Technology in Ecuador

MASKANA, I+D+ingeniería 2014 Sensing TVWS with open source technology in Ecuador José Matamoros Vargas1, Danilo Corral De Witt1, Rubén León Vásquez1, Ermanno Pietrosemoli2 1 Universidad de las Fuerzas Armadas ESPE, Sangolquí, Ecuador. 2 International Centre for Theoretical Physics, Trieste, Italy. Autores para correspondencia: {jamatamoros, drcorral, rdleon}@espe.edu.ec, [email protected] Fecha de recepción: 21 de septiembre de 2014 - Fecha de aceptación: 17 de octubre de 2014 RESUMEN La identificación de TVWS es fundamental para concientizar sobre la existencia de espectro radio eléctrico subutilizado y que podría ser utilizado para aliviar la falta de espectro existente. Estándares recientes que aplican Radio Cognitiva tales como WRAN o White-Fi pueden ser utilizados para explotar estas frecuencias. Las herramientas tradicionales utilizadas para detectar TVWS son caras difíciles de aprender. La utilización de hardware y software libre, así como un método basado en detección de energía para desarrollar una herramienta que ayude a detectar estos TVWS, es presentada para evaluar el espectro radio eléctrico en la banda UHF desde 500 MHz hasta 686 MHz en la provincia de Pichincha del Ecuador, Sudamérica. Palabras clave: TVWS, espectro, detección de energía, código abierto, Raspberry PI. ABSTRACT The identification of TVWS is fundamental to raise awareness about the existence of spectrum that is currently underutilized and that could be used to alleviate the current spectrum crunch. Recent standards that employ Cognitive Radio such as WRAN or White-Fi can then be employed for the exploitation of these frequencies. The traditional tools used to detect TVWS are expensive and difficult to master. The utilization of open hardware, software and an energy based detection method that helps detect these TVWS is developed and presented to assess the radio electric spectrum in the UHF band from 500 MHz to 686 MHz in the Pichincha province of Ecuador, South America. -

Registro Civil Identificación Y Cedulación

REGISTRO CIVIL IDENTIFICACIÓN Y CEDULACIÓN PROVINCIA CANTÓN PARROQUIA PUNTO DE ATENCIÓN TIPO DIRECCIÓN TELÉFONO EXTENSIÓN CARCHI ESPEJO EL ÁNGEL EL ANGEL AGENCIA ESMERALDAS Y SALINAS (GAD MUNICIPAL DE ESPEJO) 062977688 S/N CARCHI MONTUFAR SAN GABRIEL SAN GABRIEL AGENCIA BOLIVAR Y SALINAS (JUNTO A LA ESCUELA JOSE REYES) 062291767 S/N CARCHI TULCAN GONZÁLEZ SUÁREZ TULCAN AGENCIA BRASIL Y PANAMA ( VIA AEROPUERTO) 063731030 4001 HOSPITAL LUIS GUSTAVO CARCHI TULCAN GONZÁLEZ SUÁREZ ARCES AV. SAN FRANCISCO Y ADOLFO BEKER 062999400 4023 DAVILA ESMERALDAS ATACAMES ATACAMES ATACAMES AGENCIA CALLE D Y LA PRIMERA, SECTOR LOS ALMENDROS S/N S/N ESMERALDAS ELOY ALFARO BORBON BORBON AGENCIA JUNTA PARROQUIAL FRENTE AL PARQUE EN LA CALLE PRINCIPAL 063731040 8402 ESMERALDAS ESMERALDAS ESMERALDAS ESMERALDAS AGENCIA NUEVE DE OCTUBRE Y MALECÓN ESQUINA 063731040 8306 SIMON PLATA MATERNIDAD VIRGEN DE ESMERALDAS ESMERALDAS ARCES AV. LIBERTAD Y MANABÍ(PARADA 8) 063731040 8303 TORRES LA BUENA ESPERANZA CALLE ISIDRO AYORA ENTRE AV. MANABI Y SACOTO BOWEN, ESMERALDAS MUISNE MUISNE MUISNE AGENCIA 063731040 8401 ESQUINA ROSA ZARATE VIA GUALLABAMBA SECTOR NUEVO QUININDÉ BARRIO 3 DE MAYO ESMERALDAS QUININDE QUININDE AGENCIA 063731040 8407 (QUININDE) ESQUINA CALLE 5 DE AGOSTO ESQUINA FRENTE AL PARQUE CENTRAL, ESMERALDAS RIOVERDE RIOVERDE RIOVERDE AGENCIA 063731040 8422 JUNTO A UNA IGLESIA CATOLICA AV. ESMERALDAS ENTRE 29 DE ABRIL Y ARMADA NACIONAL BARRIO ESMERALDAS SAN LORENZO SAN LORENZO SAN LORENZO AGENCIA 063731040 8421 NUEVO HORIZONTEROBALINO IMBABURA ANTONIO ANTE -

By Under the Direction of Dr. Robert E. Rhoades Agricultural Cooperatives

THE ROLE OF WEALTH AND CULTURAL HETEROGENEITY IN THE EMERGENCE OF SOCIAL NETWORKS AND AGRICULTURAL COOPERATIVES IN AN ECUADORIAN COLONIZATION ZONE by ERIC CONLAN JONES Under the direction of Dr. Robert E. Rhoades ABSTRACT Agricultural cooperatives in Ecuador have experienced varied levels of success as well as increased difficulty staying together in the past 20 years. In addition, a trend towards greater concentration of landholdings and corresponding increases in inequality erodes land reform’s positive impact on the equitable distribution of land, albeit limited. For example, migrant laborers seek work with the new, large palmito and African palm plantations. These in-migrants are becoming more numerous than the original land-seeking pioneers who colonized northwest Ecuador's Las Golondrinas area 20-30 years ago. Research linking the areas of migration and social structure has neglected the implications of migration for the design and effectiveness of cooperative social relations, including the development of agricultural cooperatives. Drawing on quantitative and qualitative data about migration streams, villages' social networks and the social networks of agricultural cooperatives in the Las Golondrinas colonization zone of northwest Ecuador, this research demonstrates the dynamics of three processes. First, migration affects the social relations involved in colonists' economic activities, with high mobility nurturing the tendency to trust fellow villagers based on similarity of their socioeconomic status, especially in the more central town of a regional economic system. Second, cultural similarities and the cohort effects of in- migration dampen this tendency, thus altering the conditions under which capital accumulation detracts from or improves formal and informal cooperation. Third, this specifically is the case for agricultural cooperatives; at the beginning, cooperatives may be held together by wealth differences because wealthy members take on disproportionate costs (and benefits). -

Rendición De Cuentas 2018

RENDICIÓN DE CUENTAS 2018 0 COMPETENCIAS Y FUNCIONES DEL GOBIERNO AUTÓNOMO DESCENTRALIZADO DE LA PROVINCIA DE PICHINCHA COMPETENCIA 1: Planificar el desarrollo provincial y formular los correspondientes planes de ordenamiento territorial, de manera articulada con la planificación nacional, regional, cantonal y parroquial. PROGRAMA: PLANIFICACIÓN DEL DESARROLLO PROVINCIAL INVERSIÓN COMPROMETIDA GADPP 2018: USD 122.414 1 Certificación ISO 37001 (Norma anti soborno) en ejecución, a ser aplicada en la Dirección de Gestión de Compras Públicas del GADPP. Funcionamiento y servicios del sistema de información territorial provincial 11 reportes realizados sobre la actualización de información cartográfica. 2.000 personas que acceden a la plataforma del visor geográfico. 6 reportes realizados en el repositorio digital. 2.655 documentos institucionales revisados y elevados al repositorio digital. Planificación del Desarrollo Territorial. 2 Agendas zonales realizadas: Sur, Equinoccial. Evaluación PDOT 2015-2019 Base de datos POAs 2006-2018 Implementación y funcionamiento del sistema de gestión por resultados (GPR). 283 proyectos a los que se realizó seguimiento. 28 POA´s aprobados e ingresados en el sistema. 12 reportes LOTAIP realizados. 1 documento de Rendición de Cuentas 2018. Provisión de información catastral. 3 catastros elaborados por Contribución Especial de Mejoras en las obras de construcción, ensanche, rehabilitación y mejoramiento de las vías de competencia exclusiva del Gobierno Provincial. 20 expropiaciones de obras solicitadas. Catastro actualizado de bienes institucionales. 1 10 informes, permutas, comodatos, donaciones, arrendamientos y peritajes elaborados. Unidad de Tierras 276 títulos de propiedad otorgados para la formalización de la tenencia de tierras en el sector rural, varias parroquias del Cantón Quito. 37 títulos de propiedad entregados en la Zona Centro. -

Evaluating Spatial Scenarios for Sustainable Development in Quito, Ecuador

International Journal of Geo-Information Article Evaluating Spatial Scenarios for Sustainable Development in Quito, Ecuador Esthela Salazar 1,2,* , Cristián Henríquez 1,3 , Richard Sliuzas 4 and Jorge Qüense 1 1 Instituto de Geografía, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Macul 4860, Santiago, Chile; [email protected] (C.H.); [email protected] (J.Q.) 2 Departamento de Ciencias de la Tierra y la Construcción, Universidad de las Fuerzas Armadas-ESPE, Sangolquí 171103, Ecuador 3 Center for Sustainable Urban Development–CEDEUS, El Comendador 1916, Providencia, Santiago, Chile 4 Faculty of Geoinformation Science and Earth Observation, University of Twente, 7514 AE Enschede, The Netherlands; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 30 December 2019; Accepted: 20 February 2020; Published: 28 February 2020 Abstract: Peripheral urban sprawl configures new, extensive conurbations that transcend current administrative boundaries. Land use planning, supported by the analysis of future scenarios, is a guide to achieve sustainability in large metropolitan areas. To understand how urban sprawl is consuming natural and agricultural land, this paper analyzes land use changes in the metropolis of Quito, considering a combination of urban planning, natural conservation and risk areas. Using the Dyna-CLUE model we simulate spatial demands for future land uses by 2050, based on two growth scenarios: the trend scenario (unrestricted growth) and the regulated scenario, which considers two parameters—a government proposal for urban expansion areas and laws that protect natural areas. Both scenarios show how urban expansion consumes agricultural and natural areas. This expansion is backed by urban policies which do not sufficiently account for conservation areas nor for risk areas. -

De-Colonizing Water. Dispossession, Water Insecurity, and Indigenous Claims for Resources, Authority, and Territory

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) De-colonizing water Dispossession, water insecurity, and Indigenous claims for resources, authority, and territory Hidalgo Bastidas, J.P.; Boelens, R..; Vos, J. DOI 10.1007/s12685-016-0186-6 Publication date 2017 Document Version Final published version Published in Water History License CC BY Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Hidalgo Bastidas, J. P., Boelens, R., & Vos, J. (2017). De-colonizing water: Dispossession, water insecurity, and Indigenous claims for resources, authority, and territory. Water History, 9(1), 67-85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12685-016-0186-6 General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:28 Sep 2021 Water Hist (2017) 9:67–85 DOI 10.1007/s12685-016-0186-6 De-colonizing water. -

Universidad De Especialidades Turisticas

UNIVERSIDAD DE ESPECIALIDADES TURISTICAS NATIONAL TOURIST GUIDE TRAVEL THROUGH GREEN PASTURES 2 days – 1 night 3 Dutch (35 - 40 years) AGRICULTURE EXPERTS Written by: Jessica Sinchi Teacher: Sergio Lasso Quito, Ecuador November, 2014 AGROTOURISM IN PICHINCHA AND SANTO DOMINGO DE LOS TSÁCHILAS PROVINCES AUTHOR: JESSICA NOEMI SINCHI CAMPOS APPROVED BY: Signature: ________________ Signature: _________________ Professional guide: Efrain López Tutor: Sergio Lasso Signature: ________________ Signature: _________________ English teacher: Cesar Cacuango Career Coordinator: Paola Freire DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my parents for their unconditional support throughout my life. Thanks to my siblings thanks for all the support and love they have shown me throughout my career; You are one of the most beautiful blessings from God and I want to thank to my two great love ones Israel and my little boy Mateo for all their unconditional love for me and their patiently waiting for my return home. 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I would like to sincerely thank my supervisor, Prof. Efrain, for his guidance and support throughout this process of graduation. Also I would like to thank to Paola, Cesar and Sergio, especially, I express my heartfelt gratefulness for their guide and support that I believed I have learned from them. To all my friends, thanks for their friendship, it has been a wonderful experience. I cannot list all the names here, but you are always in my mind. Finally, I would like to leave the remaining space in memory of my grandma (1934 - 2014), a wonderful person and very important part of my life. This thesis is only a beginning of my journey. -

Geographic Distribution of Leishmania Species in Ecuador Based on the Cytochrome B Gene Sequence Analysis

RESEARCH ARTICLE Geographic Distribution of Leishmania Species in Ecuador Based on the Cytochrome B Gene Sequence Analysis Hirotomo Kato1,2*, Eduardo A. Gomez3, Luiggi Martini-Robles4, Jenny Muzzio4, Lenin Velez3, Manuel Calvopiña5, Daniel Romero-Alvarez5, Tatsuyuki Mimori6, Hiroshi Uezato7, Yoshihisa Hashiguchi3 1 Division of Medical Zoology, Department of Infection and Immunity, Jichi Medical University, Tochigi, Japan, 2 Laboratory of Parasitology, Department of Disease Control, Graduate School of Veterinary Medicine, Hokkaido University, Hokkaido, Japan, 3 Departamento de Parasitologia y Medicina Tropical, a11111 Facultad de Ciencias Medicas, Universidad Catolica de Santiago de Guayaquil, Guayaquil, Ecuador, 4 Departamento de Parasitologia, Insitituto de Investigacion de Salud Publica, Guayaquil, Ecuador, 5 Centro de Biomedicina, Facultad de Medicina, Universidad Central del Ecuador, Quito, Ecuador, 6 Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Life Sciences, Graduate School of Health Sciences, Kumamoto University, Kumamoto, Japan, 7 Department of Dermatology, Faculty of Medicine, University of the Ryukyus, Okinawa, Japan * [email protected] OPEN ACCESS Citation: Kato H, Gomez EA, Martini-Robles L, Muzzio J, Velez L, Calvopiña M, et al. (2016) Abstract Geographic Distribution of Leishmania Species in Ecuador Based on the Cytochrome B Gene A countrywide epidemiological study was performed to elucidate the current geographic dis- Sequence Analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 10(7): tribution of causative species of cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) in Ecuador by using FTA e0004844. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0004844 card-spotted samples and smear slides as DNA sources. Putative Leishmania in 165 sam- Editor: Ricardo Toshio Fujiwara, Universidade ples collected from patients with CL in 16 provinces of Ecuador were examined at the spe- Federal de Minas Gerais, BRAZIL cies level based on the cytochrome b gene sequence analysis.