Thesis Hum 2012 Malimela M.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chancellor of the University of Johannesburg Professor Njabulo

Chancellor of the University of Johannesburg Professor Njabulo Ndebele Honourable Former President of the Republic of South Africa and our Honorary Doctorate, Thabo Mbeki Honourable Minister of Higher Education and Training, Mrs Naledi Pandor Honourable Minister of Transport, Dr Blade Nzimande Honourable Deputy Minister of Higher Education and Training, Mr Buti Manamela Honourable Premier of Gauteng, Mr David Makhura ANC Treasurer General, Mr Paul Mashatile Former Ministers and Deputy Ministers Members of Parliament and Senior Officials from National, Provincial and Local Government Structures Former Deputy Prime Minister of Zimbabwe Professor Arthur Mutambara Honourable Ambassadors and High Commissioners Former UJ Chancellor, Ms Wendy Luhabe The Chairperson of the UJ Council, Mr Mike Teke, and current and former Members of the Council of UJ Former Vice-Chancellor, Prof Ihron Rensburg Chancellors, Chairs of Councils and Vice-Chancellors from other Universities The UJ Executive Leadership Group, Members of Senate and Distinguished Professors UJ Staff, Students and Members of the Convocation Partners from Business and Industry; Schools and Friends of UJ Distinguished Guests, Ladies and Gentleman Family members and friends, including my friends travelling from abroad My wife Dr. Jabulile Manana my sons Khathutshelo and Thendo as well as my daughter Denga I thank my parents who are here today Vho-Shavhani na Vho-Khathutshelo Marwala I also acknowledge the presence of my first school teacher Mrs. Netshilema who taught me in great one. I also acknowledge the presence of my high school principals and teachers Professor Matamba, Mr. Muloiwa and Mr. Lidzhade I also acknowledge the presence of my Chief Vhamusanda Vho-Ligege and her delegation It is indeed an honor for me to be leading one of the greatest and innovative universities in South Africa and beyond. -

Khasho August September 2010

Professionalism, Integrity, Service Excellence, Accountability and Credibility 2 Editorial Letter from the Editor Take a sneak view of the interview that At this meeting which was hosted by Khasho had with the NPA’s Executive the World Bank and the UNODC in Manager of HRM&D whose Paris, the Minister noted the efforts of responsibility, amongst others, is to ensure the Asset Recovery Inter-Agency that NPA women employees have equal Network of Southern Africa opportunities in the workplace. (ARINSA) within the Southern African region and supported the The NPA presented its first quarter need to increase the capacity of performance report before the Justice prosecutors and investigators to Portfolio Committee last month. The pursue the ‘proceeds of crime’. On 26 presentation is available on both the July, the Minister officially opened intranet and NPA website for your ARINSA’s first annual general interest. The NDPP interacted with the meeting in Pretoria, and Mr Willie media, the public and specifically with Hofmeyr shared South Africa’s key stakeholders to articulate on the valuable experiences and insights report. He presented at a public lecture from the past 10 years of the AFU’s In South Africa the month of hosted by the National Library of SA and existence. Participation in such August is recognised as women’s at the Institute for Security Studies (ISS) prestigious events is indeed a sign month. To keep up with this South and the vibrant discussions that ensued that the NPA and the South African African tradition of celebrating after the presentation are an indication justice system are making a women in August, this issue of that the public is committed to significant impact in the global Khasho shares with you articles contributing to dialogues that seek to justice landscape. -

Dosh Receives 2010 IPA FTP Prize at 29Th Istanbul Book Fair

PRESS RELEASE 3, avenue de Miremont CH – 1206 Geneva Tel: +41 22 704 1820 Fax: +41 22 704 1821 [email protected] Staff of Chechen Human Rights Magazine DOSH Receives 2010 IPA Freedom to Publish Prize at Istanbul Book Fair Against Decision of European Court of Human Rights, Trial of Turkish Publisher of Apollinaire, Recipient of IPA’s 2010 Special Award, Continues Istanbul, Geneva – 2 November 2010 The President of the International Publishers Association (IPA), Herman P. Spruijt, formally awarded, on 2 November 2010, in Istanbul the 2010 IPA Freedom to Publish Prize to Israpil Shovkhalov, Editor-in-Chief, and Viktor Kogan-Yasny, publisher of the Dosh Magazine for their exemplary courage in upholding freedom to publish. Dosh is a Chechen Human Rights magazine. The Award Ceremony took place during the 29th Istanbul Book Fair. A special Award was also given to Turkish publisher Irfan Sanci (Sel Yayıncılık). The very day of his award, an Istanbul court, ignoring a previous decison of the European Court of Human Rights, decided to keep suing him for publishing a translation of Apollinaire. He faces up to 9 years in prison. The next hearing is due on 7 December 2010. The Board of the IPA, meeting in Frankfurt on 6 October 2010, had selected Israpil Shovkhalov, Editor-in-Chief, and Viktor Kogan-Yasny, publisher of the Chechen Human Rights Magazine Dosh, as Prize-winners from among many highly commendable candidates. This year’s Award was formally presented on 2 November 2010 by IPA President Herman P. Spruijt during the 29 th Istanbul Book Fair, in an event marking the end of the international days of the Fair. -

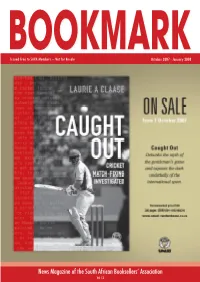

Contents FEATURES REPORTS REGULARS

Issued Free to SABA Members – Not for Resale October 2007 - January 2008 Vol 12 Contents FEATURES REPORTS REGULARS 8 Effective Education 14 IFLA Congress Exceeds 4 From the Presidents A vision for the future Expectations Desk 10 Secrets to Success Awards put Libraries in 6 SABA National One on one with award willing book Executive Committee shops the Spotlight 24 Industry Update 12 SA’s Bookselling 16 Annual Focus on SABA Landscape The facts and figures What does SABA do for 27 Africa News you? 13 Sibongile Nzimande 28 International News KZN’z new GM for Public Libraries What’s Happening in your Sector? 32 Member Listing 18 WCED sets an Example The success of good working relationships The new Executive 35 2007 Buyers Guide Committee 20 The Next Big Seller The Golden Compass 22 26 Letters of the Alphabet Literacy against violence Bookmark REGULARS From the President’s Desk he Annual Meetings are over in a strict ethical framework. (See T and I would again like to thank pg 18 for an excerpt of this talk.) those of you who attended. The new School booksellers at the confer- format was very popular as it avoid- ence expressed concern about the ed a repetition of debate and enabled publishers moving into new areas of us to listen to a number of most in- direct supply and excluding book- teresting speakers. Judging from sellers from the Technical College the comments we have received, it is book market, for instance. SABA has likely that future meetings will follow decided to try to revive the LTSM the same format and I hope that we Committee which gave us the abil- will attract even more of our mem- ity to discuss book supply matters bership to the meetings that are to be at a high level within the Education held at the delightful Vineyard Hotel Department. -

Eventsafe Company Profile

EventSafe Company Profile Contents Our Details ........................................................................................................................................................... 3 About Us .............................................................................................................................................................. 3 Our Background ................................................................................................................................................... 3 Partnership with SSG Events ............................................................................................................................... 4 Our Services ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 1. Security Solutions .................................................................................................................................... 6 1.1. Objectives ............................................................................................................................................. 6 1.2. Team ..................................................................................................................................................... 6 1.3. Compliance ........................................................................................................................................... 7 1.4. Team Training ...................................................................................................................................... -

IBBY Biennial Report 2014-2016 Tel

E L P O E P G U N Y O R F O S O K B O N O A R D L B O I N T E R N A T I O N A BIENNIAL REPORT 2014 – 2016 Nonnenweg 12 Postfach CH-4009 Basel Switzerland IBBY Biennial Report 2014-2016 Tel. +41 61 272 29 17 IBBY Biennial Report Fax +41 61 272 27 57 E-mail: [email protected] 2014 – 2016 www.ibby.org Preface: by Wally De Doncker 2 1 Membership 5 2 General Assembly 6 3 Executive Committee 8 4 Subcommittees 8 5 Executive Committee Meetings 9 6 President 11 7 Executive Committee Members 12 8 Secretariat 13 9 Finances and Fundraising 15 10 IBBY Foundation 17 11 Bookbird 17 12 Congresses 18 13 Hans Christian Andersen Awards 21 14 IBBY Honour List 24 15 IBBY-Asahi Reading Promotion Award 25 16 International Children's Book Day 26 17 IBBY Collection for Young People with Disabilities 27 18 IBBY Reading Promotion: IBBY-Yamada Fund 28 19 IBBY Children in Crisis Projects 33 20 Silent Books: Final Destination Lampedusa 38 21 IBBY Regional Cooperation 39 22 Cooperation with Other Organizations 41 23 Exhibitions 45 24 Publications and Posters 45 Reporting period: June 2014 to June 2016 Compiled by Liz Page and Susan Dewhirst, IBBY Secretariat Basel, June 2016 Cover: From International Children's Book Day poster 2016 by Ziraldo, Brazil Page 4: International Children's Book Day poster 2015 by Nasim Abaeian, UAE THE IMPACT OF IBBY Within IBBY lies a strength, which, fuelled by the legacy of Jella Lepman, has shown its impact all over the world. -

9-December-2011

The Jewish Report wishes our readers a Happy Chanukah! www.sajewishreport.co.za Friday, 09 December 2011 / 13 Kislev, 5772 Volume 15 Number 45 Sydenham Pre-Primary School is participating in the “Butterfly Project”. The Collecting 1,5 million Holocaust Museum in Houston Texas is collecting one and a half million hand- made butterflies - all of a certain size - from around the world to be exhibited in 2014. These butterflies represent the one and a half million Jewish children butterflies for kids killed who perished in the Holocaust. Each child in Sydenham Pre-Primary is making a butterfly. Ella Rosmarin, one of the Sydenham learners, holds her butterfly. in the Shoah SEE PAGE 16 The theme of butterflies is based on a poem by Pavel Friedman, who wrote it in Terezin. He died in Auschwitz in 1944. (PHOTO: ILAN OSSENDRYVER) - IN THIS EDITION - 4, 7, 14 Travelling Kosher in KZN, PE and CT 3 Climate 9 A warm 8 SAKS - change - welcome to Jewish Israel’s Jewish Report’s optimism contribution new business tempered to fixing the column - with problem Bryan Silke’s realism BusinessBrief 11 Good reads NOTE TO OUR READERS: This is the last issue of the Jewish Report for 2011. Our next issue will appear on January 20, 2012 2 SA JEWISH REPORT 09 December 2011 - 20 January 2012 SHABBAT TIMES SPONSORED BY: PARSHA OF THE WEEK Chabad spreads the PARSHAT VAYISHLACH Jacob Rabbi Ramon light this Chanukah Widmonte jumps! MICHAEL BELLING from 17:00 to 19:00 on the first night, Bnei Akiva with the public lighting of the THE SPIRIT of Chanukah this year, menorah and dreidel games, music from the evening of December 20 to and fun activities for children, OUR FOREFATHER, Ya’akov (Jacob), is a shadow- December 28, is reaching across the Rabbi Gidon Fox of the Pretoria man. -

Research, Innovation & Postgraduate Studies

UJADVANCEFUNDING AND DEVELOPMENT UNIVERSITY OF JOHANNESBURG | NEWS MAGAZINE | ISSUE 2 | VOL 8 MOVING THE WORLD FORWARD THROUGH Research, Innovation & Postgraduate Studies 4 Editor’s Note Internationalisation 5 Message from the VC 24 – 29 Meet the team UJ News Study Abroad Programme 6 UJ welcomes new Chancellor World Flavours Prof Njabulo Ndebele East Africa Executive Leadership Visits Postgraduate Centre 7 – 8 About the PGC Faculties and the PG students 30 - 36 Cumulus Green award for Funding and Support at the PGC paper on sustainable design 9 – 11 Strengthening Faculty News South African academics 37 – 41 UJ Solar Challenge vehicles 12 UJ student awarded Mandela celebrate success Rhodes Scholarship for ‘Class of 2013’ Funding and Development Research News 13 Polishing diamonds: the UJ 42 – 45 Research Chairs awarded to UJ in 2012 and De Beers story contents 14 The need for successful business Top Science researchers partnerships Record number of Doctoral graduates in one faculty Alumni 15 - 17 UJ Alumni Idols 2012 Sport News and Achievements 2 What can the Alumni Office 46 – 49 UJ Sport on a do for you? winning streak Alumni and CE Awards Visual Feature Alumni Feature 50 - 51 Competing 18 - 19 UJ Alumna vies for Miss Earth for the spotlight title in the Philippines Opinion UJ ADVANCE NOV 2012 UJ ADVANCE Community Engagement 52 - 53 Building 20 – 23 CE Student Volunteer Partnerships in Programme Building Project an unequal world CE Student Showcase Competition Hospital Project Nelson Mandela Day Women’s Day Fostering Partnerships at UJ 3 RESEARCH, INNOVATION AND POSTGRADUATE STUDIES AND POSTGRADUATE RESEARCH, INNOVATION A WORD FROM THE EDITOR Working hard to make a difference in the world The University’s Preamble to the UJ Strategic Thrusts: 2011 – 2020 is/states that UJ strives to provide education that is accessible and affordable, challenging, imaginative and innovative, and a just, responsible and sustainable society. -

Margaret T. Hite. Traditional Book Donation to Sub-Saharan Africa: an Inquiry Into Policy, Practice and Appropriate Information Provision

Margaret T. Hite. Traditional Book Donation to Sub-Saharan Africa: An Inquiry into Policy, Practice and Appropriate Information Provision. A Master’s Paper for the M.S. in L.S degree. April, 2006. 46 pages. Advisor: David Carr Abstract Traditional book donation programs are a favored method for North American clubs, service groups, libraries and individuals to help rural African community and school libraries. This study draws together book gifts and donations literature of North American and African librarians to discover whether traditional book donations from North America to Africa fulfill the needs of recipients of the aid. The theories of sustainable development and appropriate technology are used to examine African information needs and donated books are considered in terms of relevance, condition, language and reading level, and cultural appropriateness. Using this lens it is found that used book donations are not useful and may in fact do damage to libraries and literacy in developing countries. Several practical alternatives are suggested as replacement for traditional book donations. Headings: Book Gifts Gifts, contributions, etc. – Africa International book programs Information needs – Africa Libraries and socio-economic problems -- Africa Appropriate technology TRADITIONAL BOOK DONATION IN SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA: AN INQUIRY INTO POLICY, PRACTICE AND APPROPRIATE INFORMATION PROVISION by Margaret T. Hite A Master’s paper submitted to the faculty of the School of Information and Library Science of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Library Science. Chapel Hill, North Carolina April 2006 Approved by _______________________________________ David Carr 3 Table of Contents TRADITIONAL BOOK DONATION IN SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA: AN INQUIRY INTO POLICY, PRACTICE AND APPROPRIATE INFORMATION PROVISION ......................................................................................................................................... -

Remarks by the Chancellor on the Occasion of the Retirement of the Vice- Chancellor of the University of Cape Town, Professor Njabulo Ndebele 26 May 2008

Remarks by the Chancellor on the occasion of the retirement of the Vice- Chancellor of the University of Cape Town, Professor Njabulo Ndebele 26 May 2008 Professor Njabulo Ndebele is an extraordinary South African. I wanted to make that statement at the outset because in these most challenging of times we need extraordinary South Africans, people with the intellect, courage and – most of all – the integrity of Njabulo. The purpose of tonight’s gathering is specifically to celebrate his tenure as Vice-Chancellor of the University of Cape Town, one of the country’s – no, the world’s – great centres of higher learning. Having worked with him in my capacity as Chancellor since he took up the post in July 2000, I have very distinct insights on his contribution and will be sharing them with you this evening. But before I do so I would like briefly to paint a broader canvas of the life of Njabulo Ndebele – a very full life so far, and with so much still to come. Njabulo is that rare sort of person who gives intellectuals a good name. An intellectual he certainly is – of the highest order - but there is nothing abstract or cloistered about how he has chosen to live his life. He is passionately engaged and apparently unafraid to tackle the most difficult of issues, sometimes drawing fierce attacks upon himself in the process, though he is a gentle man. He is a fearless free thinker whose wellspring is principle and compassion. Besides his many vital roles at universities, culminating in the highest post at UCT, Njabulo is rightly recognised as one of the finest writers and thinkers produced by our continent. -

The Transformation of the Sacks Futeran Buildings Into the Homecoming Centre of the District Six Museum

From family business to public museum: The transformation of the Sacks Futeran buildings into the Homecoming Centre of the District Six Museum. Hayley Elizabeth Hayes-Roberts 3079780 A mini-thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree M.A. in History (with specialisation in Museum and Heritage Studies) University of the Western Cape. Supervisor: Professor Ciraj Rassool Declaration I, Hayley E. Hayes-Roberts, hereby declare that this thesis ‘From family business to public museum: The transformation of Sacks Futeran buildings into the Homecoming Centre of the District Six Museum’ is my own work and that it has not been submitted elsewhere in any form or part, and that I have followed all ethical guidelines and academic principles as expressed by the University of the Western Cape and the District Six Museum. __________________________________________________ Hayley Hayes-Roberts, 23rd November 2012, Cape Town i Acknowledgements With heartfelt thanks to the staff of the District Six Museum: Tina Smith, Chrischené Julius Mandy Sanger, Bonita Bennett, Nicky Ewers, Estelle Fester, Margaux Bergman, Thulani Nxumalo, Dean Jates, Noor Ebrahim, Joe Schaffers, Linda Fortune, ex-residents and many others for your guidance, support, encouragement and friendship. Your work ethic and passion are a source of inspiration to me. I met and engaged with many individuals during my research that informed my thinking and to each and everyone who participated, listened, and provided guidance, I give my appreciative thanks. Mike Scurr, Rennie Scurr Adendorff Architects, Owen Futeran, Adrienne Folb, The Kaplan Centre, University of Cape Town, Melanie Geuftyn and Laddie Mackeshnie, Special Collections South African National Library, Cape Town and Jocelyn Poswell, Jacob Gitlin Library were most helpful and accommodating in my requests for material, interviews and information. -

Downloaded Their Deliveries

www.sabooksellers.com Issue 75, Dec 2013 – Feb 2014 NEWS MAGAZINE OF THE SA BOOKSELLERS ASSOCIATION NEW CAPS Study available at R130.00 each. (Recommended Guides Retail are Price) now Flying High with Study & Master Study Guides 12 CAPS also in e book Cambridge University Press, P O Box 50017, V&A Waterfront, 8002 Tel 021 4127800 | Fax 021 4198418 | Email [email protected] www.cup.co.za Study Guide flyer.indd 1 2013/11/06 3:27 PM Contents REGULARS GENERAL TRADE LIBRARIES 4 From the President’s Desk 6 • SA Booksellers National Executive 12 The Frankfurt Book Fair 22 The Nation celebrates reading • A few insights from South African Committee National Book Week 2013 attendees • Bookmark • A photo report 23 The librarian of the future • The SA Booksellers Office LIASA Annual Conference • About the SA Booksellers Association 16 Open Book 24 A journey of discovery 29 Member Listing Leading the way as a world-class Audiobooks on Overdrive book festival E-BOOKS 18 Publishers going direct ACADEMIC AND EDUCATION 8 New e-book selling platforms A real threat or an imagined ambition? 26 The future of Education in SA Bundling and subscription-based How will it effect educational services on the up and up 19 RPG Online The future of metadata in South Africa bookselling? 10 A bookshop built by Escher 27 Speculation laid to rest Reconsidering your online presence 20 Bookselling in turbulent times A topical industry flooded with Changes in ownership of 11 The kids are reading opportunities Bookstore chains Does it matter which medium they use? << BACK TO CONTENTS From the President’s Desk Dear Members, models, how books are used, how long meetings have been well attended.