VOLUME A: Detailed Study of Poverty and Vulnerability in Four

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Baseline Report

Final Baseline Report on Empowering women to access safe abortion service in Gorkha, Nepal Submitted to: Executive Director Population, Health and Development Group (PHD Group) Indraeni, Dhungakhani, Sanepa, Ring Road, Lalitpur Kathmandu +977-1-5184063 Submitted by Prof. Dr.GajaNandAgrawal – Team Leader Dr.Megha Raj Dhakal – Research Officer Qualitative Mr.PramijThapa – Research Officer Quantitative Metro Apartment, Kuleshwor Kathmandu, Nepal +977-015187341 Email:[email protected] December 20, 2018 i Acknowledgements We the research team comprising of Prof. Dr. Gaja Nand Agrawal – Team Leader, Dr. Megha Raj Dhakal – Research Officer Qualitative and Pramij Thapa – Research Officer Quantitative would like to express our sincere thanks to Dr. Yagya B. Karki, Project Team Leader, Empowering women to access safe abortion service in Gorkha, Nepal for his support and guidance for the successful completion of the baseline survey work. In the meantime we would also like to thank Mr. Khadaga B. Karki, Admin/Logistics Officer, PHD Group for his overall management when the field work was undertaken for data collection.We are grateful to Ms. Anchal Thapa, Project Assistant, PHD Group for refining the tools of the survey. We would also like to express our sincere thanks to Mr. Deepak Babu Kandel, Mayor, Palungtar Municipality, Mr. Raju Gurung, Mayor, Sirnachok rural municipality and Mr. Phadindra Dhital, Mayor, Ajirkot rural municipality for their for their valuable support and inputs while the baseline data was collected in their localities. Similarly, on behalf of PHD Group, we wish to thank local health facilities and the Family Welfare Division, Department of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Population, Teku, Kathmandu for their support in carrying out the baseline survey. -

Nepal Earthquake District Profile - Gorkha OSOCC Assessment Cell 09.05.2015

Nepal Earthquake District Profile - Gorkha OSOCC Assessment Cell 09.05.2015 This report is produced by the OSOCC Assessment Cell based on secondary data from multiple sources, including the Government of Nepal, UNDAC, United Nations Agencies, non-governmental organisation and media sources. I. Situation Overview Gorkha, with a population of more than 271,000, is one of the worst-affected districts.1 The epicenter of the earthquake was in Brapok, 15km from Gorkha town. As of 6 May, 412 people have been reported killed and 1,034 injured. In the southern part of the district, food has been provided, but field observations indicate that the food supplied might not be enough for the actual population in the area. Several VDCs in the mountainous areas of Gorkha are yet to be reached by humanitarian assistance. There are no roads in these northern areas, only footpaths. The level of destruction within the district and even within VDCs varies widely, as does the availability of food. A humanitarian hub has been set up at the Chief District Officer’s (CDO) premises in Gorkha town. Reported number of people in need (multiple sources) The figures featured in this map have been collected via multiple sources (district authorities, Red Cross, local NGO, media). Where multiple figures for the same location have been reported the highest one was taken. These figures are indicative and do not represent the overall number of people in need. 1 This is an updated version of the Gorkha District Profile that was published by ACAPS on 1 May 2015. As with other mountain areas of Nepal, Gorkha contains popular locations for foreign trekkers. -

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

CARE Nepal Save the Children UNDP World Vision International

Volume III Recovery & Reconstruction Quarterly Bulletin| Gorkha September 2016 Volume III Asal Chhimekee Nepal UN Women WHO International Nepal Fellowship International Medical Corps Good Neighbors International Sajhedari Bikaas People In Need HRRP ECO- Nepal Updates United Vision Nepal Nepal Red Cross Society Oxfam Suaahara Catholic Relief Services UNICEF CARE Nepal Save the Children UNDP World Vision International Recovery & Reconstruction Quarterly Bulletin| Gorkha September 2016 Volume III July – September, 2016 Working VDC's: Shreenathkot, Aappipal, Ghairung, Bhumlichowk and Ghyalchowk, Gorkha Asal Chimekee Nepal is an organization which was registered as NGO in 2059 and was started by Pokhara Christian Community Kaski. It works in coordination with DDRC, related district government offices, like minded organizations, local communities and churches in Gorkha. The organization has been focusing on rehabilitation, reconstruction, livelihood & health support, disaster preparedness and strengthening local community together with the government bodies and local community. Some of the specific works of this organization are as follows: 1: Reconstructions of Health Post Buildings in Aappipal, Ghairung, Bhumlichowk & Ghyalchowk Except Aappipal healthpost, other health post reconstruction works has been completed and in the process on handover program to the local community within the 1st week of October, 2016 with necessary equipments and furnishing. The representatives of MoHP & DHO were also involved during the process of reconstruction. From the expert side, the technical consultant visited to healthpost construction site for monitoring and supervision of the constructional work. 2: Reconstruction of VDC building Shreentahkot VDC building reconstructions work has been started from 5th of Asoj, 2073. The reconstruction work was started formally by doing laystone foundation of the VDC building. -

Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA)

Chapter 3 Project Evaluation and Recommendations 3-1 Project Effect It is appropriate to implement the Project under Japan's Grant Aid Assistance, because the Project will have the following effects: (1) Direct Effects 1) Improvement of Educational Environment By replacing deteriorated classrooms, which are danger in structure, with rainwater leakage, and/or insufficient natural lighting and ventilation, with new ones of better quality, the Project will contribute to improving the education environment, which will be effective for improving internal efficiency. Furthermore, provision of toilets and water-supply facilities will greatly encourage the attendance of female teachers and students. Present(※) After Project Completion Usable classrooms in Target Districts 19,177 classrooms 21,707 classrooms Number of Students accommodated in the 709,410 students 835,820 students usable classrooms ※ Including the classrooms to be constructed under BPEP-II by July 2004 2) Improvement of Teacher Training Environment By constructing exclusive facilities for Resource Centres, the Project will contribute to activating teacher training and information-sharing, which will lead to improved quality of education. (2) Indirect Effects 1) Enhancement of Community Participation to Education Community participation in overall primary school management activities will be enhanced through participation in this construction project and by receiving guidance on various educational matters from the government. 91 3-2 Recommendations For the effective implementation of the project, it is recommended that HMG of Nepal take the following actions: 1) Coordination with other donors As and when necessary for the effective implementation of the Project, the DOE should ensure effective coordination with the CIP donors in terms of the CIP components including the allocation of target districts. -

VBST Short List

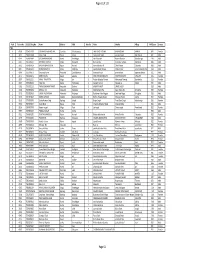

1 आिेदकको दर्ा ा न륍बर नागररकर्ा न륍बर नाम थायी जि쥍ला गा.वि.स. बािुको नाम ईभेꅍट ID 10002 2632 SUMAN BHATTARAI KATHMANDU KATHMANDU M.N.P. KEDAR PRASAD BHATTARAI 136880 10003 28733 KABIN PRAJAPATI BHAKTAPUR BHAKTAPUR N.P. SITA RAM PRAJAPATI 136882 10008 271060/7240/5583 SUDESH MANANDHAR KATHMANDU KATHMANDU M.N.P. SHREE KRISHNA MANANDHAR 136890 10011 9135 SAMERRR NAKARMI KATHMANDU KATHMANDU M.N.P. BASANTA KUMAR NAKARMI 136943 10014 407/11592 NANI MAYA BASNET DOLAKHA BHIMESWOR N.P. SHREE YAGA BAHADUR BASNET136951 10015 62032/450 USHA ADHIJARI KAVRE PANCHKHAL BHOLA NATH ADHIKARI 136952 10017 411001/71853 MANASH THAPA GULMI TAMGHAS KASHER BAHADUR THAPA 136954 10018 44874 RAJ KUMAR LAMICHHANE PARBAT TILAHAR KRISHNA BAHADUR LAMICHHANE136957 10021 711034/173 KESHAB RAJ BHATTA BAJHANG BANJH JANAK LAL BHATTA 136964 10023 1581 MANDEEP SHRESTHA SIRAHA SIRAHA N.P. KUMAR MAN SHRESTHA 136969 2 आिेदकको दर्ा ा न륍बर नागररकर्ा न륍बर नाम थायी जि쥍ला गा.वि.स. बािुको नाम ईभेꅍट ID 10024 283027/3 SHREE KRISHNA GHARTI LALITPUR GODAWARI DURGA BAHADUR GHARTI 136971 10025 60-01-71-00189 CHANDRA KAMI JUMLA PATARASI JAYA LAL KAMI 136974 10026 151086/205 PRABIN YADAV DHANUSHA MARCHAIJHITAKAIYA JAYA NARAYAN YADAV 136976 10030 1012/81328 SABINA NAGARKOTI KATHMANDU DAANCHHI HARI KRISHNA NAGARKOTI 136984 10032 1039/16713 BIRENDRA PRASAD GUPTABARA KARAIYA SAMBHU SHA KANU 136988 10033 28-01-71-05846 SURESH JOSHI LALITPUR LALITPUR U.M.N.P. RAJU JOSHI 136990 10034 331071/6889 BIJAYA PRASAD YADAV BARA RAUWAHI RAM YAKWAL PRASAD YADAV 136993 10036 071024/932 DIPENDRA BHUJEL DHANKUTA TANKHUWA LOCHAN BAHADUR BHUJEL 136996 10037 28-01-067-01720 SABIN K.C. -

WASH Cluster Nepal 4W - May 12Th 2015

WASH Cluster Nepal 4W - May 12th 2015 Please find following the analysis of the 4W data – May 12th Introduction (Round 2) This is the second round of the 4W analysis. As this is the second round and still early in the emergency response, many agencies are still planning their interventions and caseloads, hence much of the data is understandably incomplete. In the coming week/s we will receive far more comprehensive partner data and will be able to show realistic gaps. In addition, we are receiving better affected population data and there are many ongoing assessments, the results of which will help us to understand both the response data and the affected population data and enable us to deliver a far more profound analysis of the WASH response. Please assist us as we have a lot of information gaps in the data provided so far and hence the maps are not yet providing a true picture of the response. We would like to quickly move to VDC mapping including planned/reached beneficiaries. Since the first round of reporting, agencies have provided substantially more VDC‐level data – as of today, of 740 WASH activities identified, 546 of these (74%) are matched to an identified VDC ‐ this is a big improvement from last week (which had VDC data for 192 of 445 activities, or 43%) The Highlights ・ 47 Organisations – number of organisations that reported in Round 1 and/or Round 2 of the WASH 4W ・ 206 VDCs – where WASH interventions taking place/planned (in 15 districts) 4W – WASH May 12th 2015 Water0B Spread of water activities ‐ targeted Temporary -

Nepal Gorkha District Assessment Form

Nepal Gorkha District Assessment Form IDENTIFICATION AND LOCATION I2 DATE OF ASSESSMENT * I3 ENUMERATOR NAME * yyyymmdd I4 DISTRICT * I5 VDC/MUNICIPALITY * I5 VDC/MUNICIPALITY * Please specify Gorkha Bihi Chhaikampar Chumchet Lho Prok Samagaun Sirdibas Uhya Other (specify) I6 WARD * I7 VILLAGE NAME * 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Do not know I8 GPS COORDINATES GPS coordinates can only be collected when outside. latitude (x.y °) longitude (x.y °) altitude (m) accuracy (m) I9 SOURCE(S) FOR THIS ASSESSMENT None 1 2 3 or more Select the number of people you spoke to for each category . * Official (administrative) . * Village representative . * Religious leader . * Army or police . * Health worker . * Social worker . * International NGO / development partner . * Teacher . * Other local person I10 HOW MANY OF THOSE KEY INFORMANTS WERE WOMEN? * COMMUNITY PROFILE » Total population P1 ENTER THE PERCENTAGE OF THE OVERALL POPULATION WHO ARE IN THE FOLLOWING CATEGORIES. Needs to add up to 100% * * * % in normal situation % requiring assistance % requiring immediate assistance » Male P2 ENTER THE PERCENTAGE OF THE MALE POPULATION WHO ARE IN THE FOLLOWING CATEGORIES. Needs to add up to 100% * * * % in normal situation % requiring assistance % requiring immediate assistance » Female P3 ENTER THE PERCENTAGE OF THE FEMALE POPULATION WHO ARE IN THE FOLLOWING CATEGORIES. Needs to add up to 100% * * * % in normal situation % requiring assistance % requiring immediate assistance » Children P4 ENTER THE PERCENTAGE OF CHILDREN WHO ARE IN THE FOLLOWING CATEGORIES. Needs -

Strengthening the Role of Civil Society and Women in Democracy And

HARIYO BAN PROGRAM Monitoring and Evaluation Plan 25 November 2011 – 25 August 2016 (Cooperative Agreement No: AID-367-A-11-00003) Submitted to: UNITED STATES AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT NEPAL MISSION Maharajgunj, Kathmandu, Nepal Submitted by: WWF in partnership with CARE, FECOFUN and NTNC P.O. Box 7660, Baluwatar, Kathmandu, Nepal First approved on April 18, 2013 Updated and approved on January 5, 2015 Updated and approved on July 31, 2015 Updated and approved on August 31, 2015 Updated and approved on January 19, 2016 January 19, 2016 Ms. Judy Oglethorpe Chief of Party, Hariyo Ban Program WWF Nepal Baluwatar, Kathmandu Subject: Approval for revised M&E Plan for the Hariyo Ban Program Reference: Cooperative Agreement # 367-A-11-00003 Dear Judy, This letter is in response to the updated Monitoring and Evaluation Plan (M&E Plan) for the Hariyo Program that you submitted to me on January 14, 2016. I would like to thank WWF and all consortium partners (CARE, NTNC, and FECOFUN) for submitting the updated M&E Plan. The revised M&E Plan is consistent with the approved Annual Work Plan and the Program Description of the Cooperative Agreement (CA). This updated M&E has added/revised/updated targets to systematically align additional earthquake recovery funding added into the award through 8th modification of Hariyo Ban award to WWF to address very unexpected and burning issues, primarily in four Hariyo Ban program districts (Gorkha, Dhading, Rasuwa and Nuwakot) and partly in other districts, due to recent earthquake and associated climatic/environmental challenges. This updated M&E Plan, including its added/revised/updated indicators and targets, will have very good programmatic meaning for the program’s overall performance monitoring process in the future. -

![NEPAL: Gorkha - Operational Presence Map [As of 14 July 2015]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2101/nepal-gorkha-operational-presence-map-as-of-14-july-2015-1052101.webp)

NEPAL: Gorkha - Operational Presence Map [As of 14 July 2015]

NEPAL: Gorkha - Operational Presence Map [as of 14 July 2015] 60 Samagaun Partners working in Gorkha Chhekampar 1-10 11-15 16-20 21-25 26-35 Lho Bihi Prok Chunchet Partners working in Nepal Sirdibas Health 26 Keroja Shelter and NFI Uhiya 23 Ghyachok Laprak WASH 18 Kharibot Warpak Gumda Kashigaun Protection 13 Lapu HansapurSimjung Muchchok Manbu Kerabari Sairpani Thumo Early Recovery 6 Jaubari Swara Thalajung Aaruaarbad Harmi ShrithankotTar k u k ot Amppipal ArupokhariAruchanaute Education 5 Palungtar Chhoprak Masel Tandrang Khoplang Tap le Gaikhur Dhawa Virkot PhinamAsrang Nutrition 1 Chyangling Borlang Bungkot Prithbinarayan Municipality Namjung DhuwakotDeurali Bakrang GhairungTan gli ch ok Tak lu ng Phujel Manakamana Makaising Darbung Mumlichok Ghyalchok IMPLEMENTING PARTNERS BY CLUSTER Early Recovery Education Health 6 partners 5 partners 26 partners Nb of Nb of Nb of organisations organisations organisations 1 >=5 1 >=5 1 >=5 Nutrition Protection Shelter and NFI 1 partners 13 partners 23 partners Nb of Nb of Nb of organisations organisations organisations 1 >=5 1 >=5 1 >=5 WASH 18 partners Want to find out the latest 3W products and other info on Nepal Earthquake response? visit the Humanitarian Response website at http:www.humanitarianresponse.info/en/op Nb of Note: organisations Implementing partners represent the organization on the ground, erations/nepal in the affected district doing operational work, such as send feedback to 1 >=5 distributing food, tents, water purification kits etc. [email protected] Creation date:23 July 2015 Glide number: EQ-2015-000048-NPL Sources: Cluster reporting The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations. -

![Uf]/Vf K'gm;J]{If0f Ug'{Kg]{ Nfeu|Fxl Ljj/0F](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5832/uf-vf-kgm-j-if0f-ug-kg-nfeu-fxl-ljj-0f-1055832.webp)

Uf]/Vf K'gm;J]{If0f Ug'{Kg]{ Nfeu|Fxl Ljj/0F

g]kfn ;/sf/ ;+3Lo dfldnf tyf :yfgLo ljsf; dGqfno s]Gb|Lo cfof]hgf sfof{Gjog OsfO{ e"sDkLo cfjf; k'glg{df{0f cfof]hgf Hjfun, nlntk'/ uf]/vf k'gM;j]{If0f ug'{kg]{ nfeu|fxL ljj/0f . S.N G_ID RV/RS Grievant Name District VDC/MUN (P) Ward(P) Tole GP/NP WARD Slip No Remarks 1 281924 RS Nettra Bahadur Thap Gorkha Aanppipal 1 bajredanda Palungtar 3 21350 2 290180 RS Sabitri Devi Bhattrai Gorkha Aanppipal 1 bajredanda Palungtar 3 212331 3 288425 RS Jit Bahadur Rana Magar Gorkha Aanppipal 1 jal jala Palungtar 3 4 290553 RS Dhan Bahadur Rana Gorkha Aanppipal 1 judi thumka Palungtar 3 5 290114 RS Rithe Sarki Gorkha Aanppipal 1 pathivara Palungtar 3 6 288914 RS Tulka Sarki Gorkha Aanppipal 1 pathivara Palungtar 3 7 288959 RS Arjun Baniya Gorkha Aanppipal 1 pathivara Palungtar 3 8 290178 RS Sanak Bahadur Bhattrai Gorkha Aanppipal 1 pathivara Palungtar 3 9 290030 RS Jibarayal Miya Gorkha Aanppipal 2 dumre danda Palungtar 3 10 290560 RS Gurungseni Sunar Gorkha Aanppipal 2 maibal Palungtar 3 215317 11 290034 RS Damar Kumari Thapa Gorkha Aanppipal 2 maibal Palungtar 3 12 288925 RS Amar Bahadur Kuwar Gorkha Aanppipal 2 pachchyan Palungtar 3 13 290556 RS Rajendra Dhakal Gorkha Aanppipal 2 raute pani Palungtar 3 215570 14 286299 RS Sarala Devkota Gorkha Aanppipal 2 raute pani Palungtar 3 423666 15 288462 RS Bijaya Raj Devkota Gorkha Aanppipal 2 raute pani Palungtar 3 16 288920 RS Shree Niwas Devkota Gorkha Aanppipal 2 raute pani Palungtar 3 17 290055 RS Uttam Kumar Shtestha Gorkha Aanppipal 2 raute pani Palungtar 3 18 290047 RS Brendra Devkota Gorkha Aanppipal -

TSLC PMT Result

Page 62 of 132 Rank Token No SLC/SEE Reg No Name District Palika WardNo Father Mother Village PMTScore Gender TSLC 1 42060 7574O15075 SOBHA BOHARA BOHARA Darchula Rithachaupata 3 HARI SINGH BOHARA BIMA BOHARA AMKUR 890.1 Female 2 39231 7569013048 Sanju Singh Bajura Gotree 9 Gyanendra Singh Jansara Singh Manikanda 902.7 Male 3 40574 7559004049 LOGAJAN BHANDARI Humla ShreeNagar 1 Hari Bhandari Amani Bhandari Bhandari gau 907 Male 4 40374 6560016016 DHANRAJ TAMATA Mugu Dhainakot 8 Bali Tamata Puni kala Tamata Dalitbada 908.2 Male 5 36515 7569004014 BHUVAN BAHADUR BK Bajura Martadi 3 Karna bahadur bk Dhauli lawar Chaurata 908.5 Male 6 43877 6960005019 NANDA SINGH B K Mugu Kotdanda 9 Jaya bahadur tiruwa Muga tiruwa Luee kotdanda mugu 910.4 Male 7 40945 7535076072 Saroj raut kurmi Rautahat GarudaBairiya 7 biswanath raut pramila devi pipariya dostiya 911.3 Male 8 42712 7569023079 NISHA BUDHa Bajura Sappata 6 GAN BAHADUR BUDHA AABHARI BUDHA CHUDARI 911.4 Female 9 35970 7260012119 RAMU TAMATATA Mugu Seri 5 Padam Bahadur Tamata Manamata Tamata Bamkanda 912.6 Female 10 36673 7375025003 Akbar Od Baitadi Pancheswor 3 Ganesh ram od Kalawati od Kalauti 915.4 Male 11 40529 7335011133 PRAMOD KUMAR PANDIT Rautahat Dharhari 5 MISHRI PANDIT URMILA DEVI 915.8 Male 12 42683 7525055002 BIMALA RAI Nuwakot Madanpur 4 Man Bahadur Rai Gauri Maya Rai Ghodghad 915.9 Female 13 42758 7525055016 SABIN AALE MAGAR Nuwakot Madanpur 4 Raj Kumar Aale Magqar Devi Aale Magar Ghodghad 915.9 Male 14 42459 7217094014 SOBHA DHAKAL Dolakha GhangSukathokar 2 Bishnu Prasad Dhakal