The Mean World Effects of Reality Television

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COM Outlook Spring 2006

Nova Southeastern University NSUWorks COM Outlook College of Osteopathic Medicine Spring 4-1-2006 COM Outlook Spring 2006 College of Osteopathic Medicine Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/hpd_com_outlook Part of the Osteopathic Medicine and Osteopathy Commons NSUWorks Citation College of Osteopathic Medicine, "COM Outlook Spring 2006" (2006). COM Outlook. 34. https://nsuworks.nova.edu/hpd_com_outlook/34 This Magazine is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Osteopathic Medicine at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in COM Outlook by an authorized administrator of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOVA SOUTHEASTERN UNIVERSITY COM Outlook College of Osteopathic Medicine Spring 2006 Volume 7, Number 2 1 ti ~ I it,_., ,, ..... ~;; / c 0 ~ NSU NSU-COMs Health Care Outreach Spans the Globe Deans Message Over the past year, the societies, which you can read about in greater detail in this Office of the President of issue of COM Outlook. Effective in July when the 2006-07 NSU has implemented a academic year commences, the college will be launching Quality Enhancement 12 academical societies, with each initially comprising 40 Plan. This plan involves students (20 from the M1 class; 20 from the M2 class) as having the 16 NSU well as two faculty advisors. The goals of these societies, colleges and centers which are similar to academic fraternities, include assess what programs enhancing student-faculty interaction, enriching student they want to establish interaction across classes, facilitating professional or those they are just development, and providing a sense of community for beginning to touch on students, faculty, and alumni. -

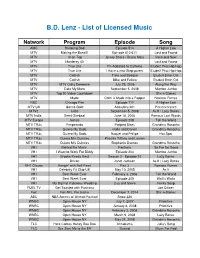

B.D. Lenz - List of Licensed Music

B.D. Lenz - List of Licensed Music Network Program Episode Song AMC Breaking Bad Episode 514 A Higher Law MTV Making the Band II Episode 610 611 Lost and Found MTV 10 on Top Jersey Shore / Bruno Mars Here and Now MTV Monterey 40 Lost and Found MTV True Life I'm Addicted to Caffeine Etude2 Phat Hip Hop MTV True Life I Have a new Step-parent Etude2 Phat Hip Hop MTV Catfish Trina and Scorpio Etude4 Bmin Ost MTV Catfish Mike and Felicia Etude4 Bmin Ost MTV MTV Oshq Deewane July 29, 2006 Along the Way MTV Date My Mom September 5, 2008 Mumbo Jumbo MTV Top 20 Video Countdown Stix-n-Stones MTV Made Colin is Made into a Rapper Noxious Fumes NBC Chicago Fire Episode 711 A Higher Law MTV UK Gonzo Gold Acoustics 201 Perserverance MTV2 Cribs September 5, 2008 As If / Lazy Bones MTV India Semi Girebaal June 18, 2006 Famous Last Words MTV Europe Gonzo Episode 208 Tell the World MTV TR3s Pimpeando Pimped Bikes Grandma Rosocha MTV TR3s Quiero My Boda Halle and Daneil Grandma Rosocha MTV TR3s Quiero My Boda Raquel and Philipe Hot Spot MTV TR3s Quiero Mis Quinces Priscilla Tiffany and Lauren MTV TR3s Quiero Mis Quinces Stephanie Duenas Grandma Rosocha VH1 Behind the Music Fantasia So Far So Good VH1 I Want to Work For Diddy Episode 204 Mumbo Jumbo VH1 Brooke Knows Best Season 2 - Episode 10 Lazy Bones VH1 Driven Janet Jackson As If / Lazy Bones VH1 Classic Hangin' with Neil Peart Part 3 Noxious Fumes VH1 Celebrity Fit Club UK May 10, 2005 As If VH1 Best Week Ever February 3, 2006 Tell the World VH1 Best Week Ever Episode 309 Walt's Waltz VH1 My Big Fat -

The Hunger Games: an Indictment of Reality Television

The Hunger Games: An Indictment of Reality Television An ELA Performance Task The Hunger Games and Reality Television Introductory Classroom Activity (30 minutes) Have students sit in small groups of about 4-5 people. Each group should have someone to record their discussion and someone who will report out orally for the group. Present on a projector the video clip drawing comparisons between The Hunger Games and shows currently on Reality TV: (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wdmOwt77D2g) After watching the video clip, ask each group recorder to create two columns on a piece of paper. In one column, the group will list recent or current reality television shows that have similarities to the way reality television is portrayed in The Hunger Games. In the second column, list or explain some of those similarities. To clarify this assignment, ask the following two questions: 1. What are the rules that have been set up for The Hunger Games, particularly those that are intended to appeal to the television audience? 2. Are there any shows currently or recently on television that use similar rules or elements to draw a larger audience? Allow about 5 to 10 minutes for students to work in their small groups to complete their lists. Have students report out on their group work, starting with question #1. Repeat the report out process with question #2. Discuss as a large group the following questions: 1. The narrator in the video clip suggests that entertainments like The Hunger Games “desensitize us” to violence. How true do you think this is? 2. -

City Manager Interviews Set Education Is Putting Its Selection Currently Sits in Seventh Place with of a New Director of Schools on 2,859 Points After Day 1

T U E S D A Y 162nd YEAR • NO. 21 MAY 24, 2016 CLEVELAND, TN 16 PAGES • 50¢ Sheriff accused of ‘conduct unbecoming’ By BRIAN GRAVES She said it was not her belief the sheriff Banner Staff Writer "of his own volition took [the BCSO Facebook] page down." Watson issues response Sheriff Eric Watson was accused of "I think that someone who may or may "conduct unbecoming" and being unre- not be in this room told him to, and I sponsive to a constituent's concerns dur- thank them," Williams said. to residents’ complaints ing Monday night's work session of the She said after the May 2014 Republican Bradley County Commission. primary when Watson won his office By BRIAN GRAVES During a meeting light on business, it because there was no Democratic opposi- Banner Staff Writer was the comments by two local residents tion, one of her daughters posted on her Bradley County Sheriff Eric Watson has responded to accusa- concerning the sheriff which took the Facebook page "a comment about him." tions made against him at Monday night’s County Commission spotlight. She did not give any specifics of the post- meeting after hearing a recording of that session Tuesday morn- Debbie Williams, who admitted to being ing. ing. a supporter of former Sheriff Jim Ruth, "It was true. The then-superintendent of In response to the comments made by Bradley County resident said she wanted to discuss the lawsuit schools and her principal called her in," Debbie Williams to commissioners during a work session, the against Watson and the county by the she said, noting her daughter had been Banner photo, BRIAN GRAVES sheriff said he appreciated “her honesty in expressing her sup- DEBBIE WILLIAMS addressed the Bradley American Atheists and a local "Jane Doe." told "He could sue you." port, past and present, for the former sheriff.” "What I'm in fear of is more lawsuits Williams said they researched U.S. -

Performing the Self on Survivor

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Texas A&M Repository TEMPORARILY MACHIAVELLIAN: PERFORMING THE SELF ON SURVIVOR An Undergraduate Research Scholars Thesis by REBECCA J. ROBERTS Submitted to the Undergraduate Research Scholars program at Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the designation as an UNDERGRADUATE RESEARCH SCHOLAR Approved by Research Advisor: Dr. James Ball III May 2018 Major: Performance Studies Psychology TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT ............................................................................................................................. 1 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ........................................................................................................ 2 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................... 3 CHAPTERS I. OUTWIT. OUTPLAY. OUTLAST ......................................................................... 8 History of Survivor ............................................................................................ 8 Origin Story of Survivor .................................................................................. 10 Becoming the Sole Survivor ............................................................................ 12 II. IDENTITY & SELF-PRESENTATION ................................................................ 17 Role Performance ........................................................................................... -

Reality Television 1

Reality Television 1 Reality Television: Understanding the Genre and Viewer Motivations and Effects Matthew Lombard Mahdee T. Ali Min-Ju Chung Matthew Dissinger Amanda Scheiner Kendra Todd (All authors except first author are students) Department of Broadcasting, Telecommunications and Mass Media School of Communications and Theater Temple University Philadelphia, PA 19122 Phone: (215) 204-7182 E-mail: [email protected] A class project by the students and instructor of BTMM 5114 Communication Research Methods in Spring 2003 Reality Television 2 Reality Television: Toward Understanding the Genre and Viewer Motivations and Effects Abstract This paper examines the appeal behind and the potential effects of the recent phenomenonal growth in reality television programming. As part of a review of the limited scholarly research but substantial popular commentary about these programs, a specific definition that captures the core characteristics of the genre is presented, the key characteristics of 130 current programs are reported, and the results of an exploratory online survey regarding the reasons people watch these programs and the effects of this viewing is presented. Reality Television 3 Reality Television: Understanding the Genre and Viewer Motivations and Effects ”What new could be said about reality shows? Well, with programs like 'American Idol,' 'The Bachelor,' and 'Joe Millionaire' dominating the airwaves and receiving high TV ratings, the demand for these shows is apparent. But the important question is, why?” (Hudson, 2003) Over 10 million people watched the season premier of the fourth installment of ABC’s The Bachelor/Bachelorette franchise (http://www.chron.com/cs/CDA/story.hts/ae/tv/1858168). FOX’s Joe Millionaire finale in spring 2003 drew 40 million viewers and 40% of adults 18-49 watching television at the time (Local & National Audiences, 2003). -

BRAND NAME PRODUCTS Predicting Market Success New

pass_a01ffirs.qxd 7/25/06 11:48 AM Page v PrediPredictingcting MarketMarket SuccessSuccess New Ways to Measure Customer Loyalty and Engage Consumers with Your Brand ROBERT PASSIKOFF, PHD John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pass_a01ffirs.qxd 7/25/06 11:48 AM Page viii pass_a01ffirs.qxd 7/25/06 11:48 AM Page i Praise for Predicting Market Success “Brand marketing is at a crossroads, and Robert Passikoff shows the way to the future—shattering conventional branding wisdom with one hand, and giving actionable advice with the other. Predicting Market Success delivers the key in- gredients for breakthrough marketing strategies: a clear-headed understanding of brands, and a predictive approach to measuring them.” Marc E. Babej President, Reason, Inc. “In the newly created world of utility deregulation, companies like KeySpan need to be able to differentiate themselves from their competitors. Predicting Market Success provides an easy to understand manual for applying engagement metrics to the brand, and defining what values create differentiation to create a successful brand platform for success.” Bob Catell Chairman & CEO, KeySpan Energy “Managers who cannot accurately measure and predict the performance of their brands cannot succeed. They are doomed to failure. This book provides an excellent road map with proven measurement tools. If managers follow it, they will not just succeed, they will dominate their competition.” Larry Chiagouris, PhD Associate Professor of Marketing, Lubin School of Business, Pace University “In a world where any marketer’s most important skill is dealing with con- stant change, Robert Passikoff is consistently the best signpost for what will happen next. His book will help marketers be more nimble and more purpose- ful in our nimbleness. -

ABSTRACT Stereotypes of Asians and Asian Americans in the U.S. Media

ABSTRACT Stereotypes of Asians and Asian Americans in the U.S. Media: Appearance, Disappearance, and Assimilation Yueqin Yang, M.A. Mentor: Douglas R. Ferdon, Jr., Ph.D. This thesis commits to highlighting major stereotypes concerning Asians and Asian Americans found in the U.S. media, the “Yellow Peril,” the perpetual foreigner, the model minority, and problematic representations of gender and sexuality. In the U.S. media, Asians and Asian Americans are greatly underrepresented. Acting roles that are granted to them in television series, films, and shows usually consist of stereotyped characters. It is unacceptable to socialize such stereotypes, for the media play a significant role of education and social networking which help people understand themselves and their relation with others. Within the limited pages of the thesis, I devote to exploring such labels as the “Yellow Peril,” perpetual foreigner, the model minority, the emasculated Asian male and the hyper-sexualized Asian female in the U.S. media. In doing so I hope to promote awareness of such typecasts by white dominant culture and society to ethnic minorities in the U.S. Stereotypes of Asians and Asian Americans in the U.S. Media: Appearance, Disappearance, and Assimilation by Yueqin Yang, B.A. A Thesis Approved by the Department of American Studies ___________________________________ Douglas R. Ferdon, Jr., Ph.D., Chairperson Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved by the Thesis Committee ___________________________________ Douglas R. Ferdon, Jr., Ph.D., Chairperson ___________________________________ James M. SoRelle, Ph.D. ___________________________________ Xin Wang, Ph.D. -

Classrooms Piling High

UNIVERSITY OF NORTH FLORIDA March www.unfspinnaker.com 14 Volume 30, Issue 26 2007 Wednesday Classrooms piling high Administration searches for answer to tight classroom space in fall 2007 BY SARAH DIENER ASSISTANT NEWS EDITOR The University of North Florida’s Space Committee is finding ILLUSTRATION: new ways to accommodate classes during the Student Union con- ROBERT K. PIETRZYK struction planned for summer 2007. Currently, nearly 100 classes are in need of space for the Fall 2007 semester. Committee members said they are UNF faculty confident finding spaces for the classes will not be a problem. “We’re in as good of shape as we can be,” said Joann Campbell, lowest paid associate vice president for academic affairs. PHO Over the course of campus construction, which has included T O ILLUSTRATION: JEN QUINN O ILLUSTRATION: the demolition of Building 11 and future removal of the portables near lots 3 and 4, many classrooms have been eliminated or made in state unavailable for student use, said Shari Shuman, vice president of administration and finance. To compensate for the missing class- BY MATT COLEMAN rooms, the Space Committee has planned new areas of FEATURES EDITOR See ROOM, page 4 Professors at the University of North Florida are the lowest paid out of all 11 public universi- ties in the state, according to a study by UNF computing profes- sor Dr. William Klostermeyer. SB 228 Bright Futures SB 850 Technology fee HB 289 Textbook pricing The study showed UNF What’s ranked last among the other 11 WHAT IT MEANS WHAT IT MEANS WHAT IT MEANS schools with an average salary of $59,466, more than $10,000 below going on in l l l Students may apply Bright State universities may Some textbooks sold in on- the state average of $71,994. -

La Construcción Discursiva Del Espectador En Los Reality Shows. El Caso De Gran Hermano Del Pacífico

FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS Y ARTES DE LA COMUNICACIÓN La construcción discursiva del espectador en los reality shows. El caso de Gran Hermano del Pacífico. Tesis para optar el Título de LICENCIADA EN PUBLICIDAD Presentada por CYNTHIA INGRID CABREJOS CALIENES Lima 2007 INTRODUCCIÓN El presente trabajo de investigación lleva como título: “La construcción discursiva del espectador en los reality shows. El caso de Gran Hermano del Pacífico”. Partiendo de las repercusiones sociales que este formato ha tenido en el plano social e individual, me interesa centrar mi análisis en esta nueva forma de hacer televisión que explota día a día la publicidad de la intimidad y el entretenimiento como recursos válidos para ganar audiencias. Todos sabemos que la televisión ejerce una fuerte influencia en sus televidentes, especialmente en la forma en la que estos se relacionan con su entorno. Sin duda, las imágenes de la televisión de hoy representan a su espectador, en la forma en que este concibe su sociedad y además, en cuáles son sus hábitos de consumo. Por otro lado, tenemos que la forma en la que estos reality shows presentan los objetos que exhiben y cuánto exhiben de ellos, es muestra de su papel por construir a un tipo de espectador ideal. Como un libro que ha sido escrito para un lector que idealmente interpreta y comprende los contenidos de la forma que lo ha concebido el autor, los reality shows establecen marcas enunciativas para atribuirle a su espectador diferentes competencias que finalmente terminen por fidelizarlo y engancharlo al drama. Precisamente la pregunta que esta investigación pretende responder es cómo el discurso de los realities (concentrándose particularmente en el de Gran Hermano) construye a un espectador ideal omnisciente y omnividente. -

GRANDPA "Pilot" 1/21/15 by Daniel Chun ©2015, ABC Studios. All

GRANDPA "Pilot" 1/21/15 by Daniel Chun ©2015, ABC Studios. All rights reserved. This material is the exclusive property of ABC Studios and is intended solely for the use of its personnel. Distribution to unauthorized persons or reproduction, in whole or in part, without the written consent of ABC Studios is strictly prohibited. Grandpa 1. COLD OPEN INT. A DIMLY-LIT ROOM - NIGHT CLOSE UP on JIMMY’s handsome face, with the eyes and the hair and the sexy everything. JAZZY music plays faintly underneath. Jimmy stares right at camera - intense, smoldering, searching. JIMMY Hah! There you are, you little bastard. REVEAL that he’s looking in the mirror of a men’s room. He finds and plucks a grey hair from the middle of his head. He checks himself out again and smiles: perfect. He walks out. Note - the following is an evolving master shot using a combination of motion control and time lapse. It’s like the guy who shot Birdman had sex with the guy who shot the Steve Carell motion control shot in Crazy Stupid Love and they had a baby that was this shot. The funniest, coolest, sexiest opening to a comedy pilot ever. No pressure. INT. JIMMY’S RESTAURANT - CONTINUOUS Jimmy walks down the hall toward the main dining room. The song gets louder and we hear the lyrics: ...and all the girls dreamed that they’d be your partner, they’d be your partner and--” “YOU’RE SO VAIN” plays as Jimmy strolls into his crowded, old- school-cool restaurant, Jimmy's. -

Harsh Realities: Substantial Similarity in the Reality Television Context

HARSH REALITIES: SUBSTANTIAL SIMILARITY IN THE REALITY TELEVISION CONTEXT Daniel Fox* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ........................................... 224 II. THE "SIMPLE" LIFE: DEVELOPMENT AND EVOLUTION OF SUBSTANTIAL SIMILARITY ANALYSIS IN THE SECOND AND NINTH CIRCUITS .................................... 227 A. The Basic Elements of Copyright Infringement ....... 227 B. Substantial Similarity: Introduction and Related D octrines ............................................ 227 C. The Test for Substantial Similarity: Second and Ninth Circuit Formulations ................................. 230 1. Second Circuit: Bifurcating "Similarity" . ........ 230 2. Ninth Circuit: Extrinsic-Intrinsic Distinction ..... 231 III. THE BIGGEST LOSER(S): METCALF AND CBS ............ 234 A . M etcalf v. Bochco ................................... 235 1. O verview ........................................ 235 2. A nalysis ......................................... 237 B. CBS v. A BC ......................................... 242 1. O verview ........................................ 242 2. A nalysis ......................................... 245 IV. EXTREME MAKEOVER?: POST METCALF JURISPRUDENCE .......................................... 248 * Editor, UCLA Law Review, Volume 54. J.D. Candidate, UCLA School of Law, 2007; A.B., Harvard University, 2004. I thank Professor David Ginsburg for his invaluable gui- dance, insight, and support at every stage of this Comment's development. I also thank Eliot Hamlisch, Jen Ringel, Eric Black, Matt Segneri, Allison