Openair@RGU the Open Access Institutional Repository at Robert

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Restatement Redux

Vanderbilt Law Review Volume 48 Issue 6 Issue 6 - November 1995 Article 3 11-1995 Restatement Redux Anita Bernstein Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr Part of the Torts Commons Recommended Citation Anita Bernstein, Restatement Redux, 48 Vanderbilt Law Review 1663 (1995) Available at: https://scholarship.law.vanderbilt.edu/vlr/vol48/iss6/3 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vanderbilt Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship@Vanderbilt Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BOOK REVIEW Restatement Redux PRODUCT LIABILITY. By Jane Stapleton.* Butterworths, 1994. Pp. xxvii, 384, index. $50.00 Reviewed by Anita Bernstein** I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................... 1664 II. THE VALUE OF COMMON-LAw RESTATEMENT: A RETROSPECTIVE .............................................................. 1666 A. The Restatement at Century's End ........................ 1667 1. The First Problem of Variation .................. 1669 2. The Second Problem of Variation .............. 1671 B. Some Benefits of Restatement ................................ 1675 III. CAN PRODUCTS LIABILITY BE RESTATED? A THREE- QUESTION FRAMEWORK ..................................................... 1677 A. What is the Problem? ............................................. 1678 B. To Whom is the Solution Addressed? ......... ........ ... 1683 C. Do Normative PrinciplesGuide -

Conversations with Professor Peter Frederic Cane by Lesley Dingle1 and Daniel Bates2

Conversations with Professor Peter Frederic Cane by Lesley Dingle1 and Daniel Bates2 10th July 2012 This is the fourth interview for the Eminent Scholars Archive with an incumbent of the Arthur Goodhart Visiting Professor of Legal Science. Peter Cane is professor at the John Fleming Centre for Advancement of Legal Research at the Australian National University, Canberra. He holds the Goodhart chair jointly with his wife Professor Jane Stapleton. Interviewer: Lesley Dingle, her questions and topics are in bold type Professor Cane’s answers are in normal type. Comments added by LD, in italics. All footnotes added by LD. 1. Professor Cane, normally at this juncture I would be interviewing the incumbent Goodhart Professor as a follow up to a first interview, and would concentrate on how the time during the tenure had transpired. In your case, we are faced with an interesting circumstance, because the first interview was with Professor Stapleton. So, here we are, at the end of the academic year but, instead of just a backward glance, I hope we can spend a good deal of the interview looking at your early career, as well as some reflections of your time here. You and Professor Stapleton constitute the fourth holder of the Professorship, but you are the fifth incumbent to be interviewed. So, briefly, could we look at your early career, how it developed, and then come to the Goodhart material and perhaps at the end, very broadly, some aspects of your personal research interests? You were born in Maitland in New South Wales in 1950. Correct. -

Professor Barbara Jane Stapleton

Jane Stapleton citation Chancellor, it gives me great pleasure to present to you Barbara Jane Stapleton. The honorary degree of Doctor of Laws (honoris causa) is being awarded to Professor Jane Stapleton in acknowledgement of her distinguished service to the law and the legal profession in Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States. Professor Stapleton is internationally regarded for her expertise in the fields of tort and personal injury law. She has pursued this work at the highest level across four decades, including academic and leadership roles, research and consultancies on complex cases within her field. Born in Sydney in 1952, Professor Stapleton was initially educated in science – she earned a Bachelor of Science with First Class Honours from the University of New South Wales, and a PhD in Chemistry at the University of Adelaide. Soon after, Jane made a critical decision to change her career to law. She received a Bachelor of Laws with First Class Honours and received the University Medal from the Australian National University. She went on to complete a D.Phil in Law at the University of Oxford, Balliol College – this was to be her second of three doctorates, many years later receiving a Doctor of Civil Law from the University of Oxford. Professor Stapleton was admitted as a Barrister of the Supreme Court of New South Wales in 1981, and to the High Court of Australia in 1984. In the 1980s and '90s she held various academic positions with the University of Sydney Law School, Trinity College, and Balliol College, Oxford. By 1996 she had been made Reader in Law at the University of Oxford. -

Conversations with Professor Barbara Jane Stapleton by Lesley Dingle and Daniel Bates First Interview: 6 February 2012 This Is

Conversations with Professor Barbara Jane Stapleton by Lesley Dingle1 and Daniel Bates2 First Interview: 6th February 2012 This is the fourth interview for the Eminent Scholars Archive with an incumbent of the Arthur Goodhart Visiting Professor of Legal Science. Jane Stapleton is a professor in the Faculty of Law at the Australian National University, Canberra and also the Ernest E. Smith, Professor of Law at the University of Texas at Austin. She holds the Goodhart chair jointly with her husband Professor Peter Cane, the first time the position has been a joint appointment. Interviewer: Lesley Dingle, her questions and topics are in bold type Professor Stapleton’s answers are in normal type. Comments added by LD, in italics. All footnotes added by LD. 1. Professor Stapleton, you are the fourth Goodhart Professor that I have had the pleasure of interviewing for the archive. We are making a tradition of hearing the views of the Goodhart incumbents at the start and end of their tenure. So I am extremely grateful to you for agreeing to add to the archive. Can I start by asking you what you hope to achieve in your time here? Yes, I am hoping to map out a book about causation and consequences in common law and private law. I have done quite a bit of work on that over the last few years and I thought this was the time to draw it all together and provide the structure and start writing the book. 2. I notice that you are organising a series of Goodhart seminars on private and public law. -

Proquest Dissertations

A NOVEL APPROACH TO THE LAW: THE CASE FOR AN EXPANDED STUDY OF CANADIAN LAW AND LITERATURE by David L. Steeves Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Laws at Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia April 2009 © Copyright by David L. Steeves, 2009 Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-50276-1 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-50276-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

British Academy New Fellows 2015 Fellows Professor Janette Atkinson

British Academy New Fellows 2015 Fellows Professor Janette Atkinson FMedSci Emeritus Professor, University College London; Visiting Professor, University of Oxford Professor Oriana Bandiera Professor of Economics, Director of STICERD, London School of Economics Professor Melanie Bartley Emeritus Professor of Medical Sociology, University College London Professor Christine Bell Professor of Constitutional Law, Assistant Principal and Executive Director, Global Justice Academy, University of Edinburgh Professor Julia Black Professor of Law and Pro Director for Research, London School of Economics and Political Science Professor Cyprian Broodbank John Disney Professor of Archaeology and Director, McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, University of Cambridge Professor David Buckingham Emeritus Professor of Media and Communications, Loughborough University; Visiting Professor, Sussex University; Visiting Professor, Norwegian Centre for Child Research Professor Craig Calhoun Director and School Professor, London School of Economics Professor Michael Carrithers Professor of Anthropology, Durham University Professor Dawn Chatty Professor of Anthropology and Forced Migration, University of Oxford Professor Andy Clark FRSE Professor of Logic and Metaphysics, University of Edinburgh Professor Thomas Corns Emeritus Professor of English Literature, Bangor University Professor Elizabeth Edwards Professor of Photographic History, Director of Photographic History Research Centre, De Montfort University Professor Briony Fer Professor of Art History, -

The Sydney Law Review Vol40 Num4

volume 40 number 4 december 2018 the sydney law review articles Non-State Policing, Legal Pluralism and the Mundane Governance of “Crime” – Amanda Porter 445 The Liability of Australian Online Intermediaries – Kylie Pappalardo and Nicolas Suzor 469 Adolescent Family Violence: What is the Role for Legal Responses? – Heather Douglas and Tamara Walsh 499 Contracts against Public Policy: Contracts for Meretricious Sexual Services – Angus Macauley 527 before the high court Australian Securities and Investments Commission v Kobelt: Evaluating Statutory Unconscionability in the Cultural Context of an Indigenous Community – Sharmin Tania and Rachel Yates 557 corrigendum 571 EDITORIAL BOARD Elisa Arcioni (Editor) Celeste Black (Editor) Tanya Mitchell Emily Crawford Joellen Riley John Eldridge Wojciech Sadurski Emily Hammond Michael Sevel Sheelagh McCracken Cameron Stewart STUDENT EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Angus Brown Tim Morgan Courtney Raad Book Review Editor: John Eldridge Before the High Court Editor: Emily Hammond Publishing Manager: Cate Stewart Correspondence should be addressed to: Sydney Law Review Law Publishing Unit Sydney Law School Building F10, Eastern Avenue UNIVERSITY OF SYDNEY NSW 2006 AUSTRALIA Email: [email protected] Website and submissions: <https://sydney.edu.au/law/our-research/ publications/sydney-law-review.html> For subscriptions outside North America: <http://sydney.edu.au/sup/> For subscriptions in North America, contact Gaunt: [email protected] The Sydney Law Review is a refereed journal. © 2018 Sydney Law Review and authors. ISSN 0082–0512 (PRINT) ISSN 1444–9528 (ONLINE) Non-State Policing, Legal Pluralism and the Mundane Governance of “Crime” Amanda Porter Abstract Faced with the problem of rising incarceration rates, there has been an emerging discourse in recent years about the need to decolonise justice for Indigenous Australians. -

Recent Books

RECENT BOOKS ART LAW Art Law: Rights and Liabilities of Creators and Collectors, Volumes I & II. Franklin Feldman & Stephen E. Weil, with the collaboration of Susan Duke Biederman. Little, Brown & Company, Boston, 1986. Pp. xxxiii, 677; xxxiii, 733. $160.00. BANKRUPTCY LAW The Logic and Limits of Bankruptcy Law. Thomas H. Jackson. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass., 1986. Pp. 287. $25.00. BIOGRAPHY Zechariah Chafee, Jr.: Defender of Liberty and Law. Donald L. Smith. Harvard Uni- versity Press, Cambridge, Mass., 1986. Pp. x, 355. $25.00. CIVIL RIGHTS The Evolution of Rights in Liberal Theory. Ian Shapiro. Cambridge University Press, New York, 1986. Pp. x, 326. Cloth $39.50. Paper $11.95. Natural Rights and Natural Law: The Legacy of George Mason. Robert P. Davidow, ed. The George Mason University Press, Fairfax, Vir., 1986. Pp. v, 264. Paper $12.50. Swann's Way: The School Busing Case & the Supreme Court. Bernard Schwartz. Ox- ford University Press, New York, 1986. Pp. 245. $19.95. COMMON LAW Legal Theory and Common Law. William Twining, ed. Basil Blackwell Ltd., New York, 1986. Pp. viii, 267. $45.00. COMPARATIVE LAW The Faces of Justice and State Authority: A Comparative Approach to the Legal Pro- cess. Mirjan R. Damaska. Yale University Press, New Haven, Conn., 1986. Pp. xi, 247. $26.00. COMPUTER LAW Bernacchi on Computer Law: A Guide to the Legal and Management Aspects of Com- puter Technology. Volumes 1 & 2. Richard L. Bernacchi, Peter B. Frank & Norman Statland. Little, Brown & Company, Boston, 1986. Pp. xxxiv, 1056. $160.00. CONSTITUTIONAL LAW American ConstitutionalLaw: Introductory Essays and Selected Cases (8th ed.). -

The Honor of Private Law

ARTICLES THE HONOR OF PRIVATE LAW Nathan B. Oman* While combativeness is central to how our culture both experiences and conceptualizes litigation, we generally notice it only as a regrettable cost. This Article offers a less squeamish vision, one that sees in the struggle of people suing one another a morally valuable activity: the vindication of insulted honor. This claim is offered as a normative defense of a civil recourse approach to private law. According to civil recourse theorists, tort and contract law should be seen as empowering plaintiffs to act against defendants, rather than as economically optimal incentives or as a means of enforcing duties of corrective justice. The justification of civil recourse must answer three questions. First, under what circumstances—if any—is one justified in acting or retaliating against a wrongdoer? Second, under what circumstances does the state have reasons for providing a mechanism for such action? Finally, how are the answers to these questions related to the current structure of our private law? This Article offers the vindication of wronged honor as an answer to these three questions. First, I establish the historical connection between honor and litigation by looking at the quintessential honor practice, dueling. Then I argue that the vindication of honor is normatively attractive. I do this by divorcing the idea of honor from unsavory associations with violence and aristocracy, showing how it can be made congruent with certain core modern concerns. In particular, when insulted parties act against wrongdoers, they reestablish the position of respect and equality that the insult upset. I then show how having the state provide plaintiffs with a means of vindicating their honor avoids making the political community complicit in the humiliation of its citizens and provides those citizens with a means of exercising their agency in ways that provide a foundation for self-respect. -

Report 2007 Pp

Annual Review 2006: Research and Activities Contents BRITISH INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AND COMPARATIVE LAW GOVERNANCE v ADVISORY COUNCIL vii STAFF AND CONSULTANTS xi INTERNATIONAL AND COMPARATIVE LAW QUARTERLY BOARD OF EDITORS xviii DIRECTOR’S ANNUAL REPORT TO MEMBERS 1 RESEARCH PROJECTS 18 EUROPEAN AND COMPARATIVE LAW PROGRAMME 18 Competition Law Forum 20 Product Liability Forum 33 Tort Law Centre 39 The Centre of French Law 42 European Financial and Corporate Law Centre 43 Legalization of Public Documents between EU Member States 48 Application of the Brussels I Regulation on Jurisdiction and the Recognition and Enforcement of Judgments in Civil and Commercial Matters in England & Wales 52 INTERNATIONAL LAW PROGRAMME 53 Private International Law 55 State Jurisdiction in a Global Environment: Rethinking Extraterritoriality 67 Investment Treaty Forum 69 Evidence Before International Courts and Tribunals 75 Damages in International Law 79 International Economic Law and the WTO 82 Promotion of Democratization and Human Rights in Iran 88 LAW AND DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME 93 International Trade Law Aspects of Exporting Morphine and Codeine from Afghanistan 93 iii Armenian Public Sector Reform Programme 94 Advocates for International Development Training Programme 95 RESEARCH PROFILES 96 BIBLIOGRAPHY 109 PUBLICATIONS 115 CONFERENCES, LECTURES AND OTHER EVENTS 128 SPONSORS 133 ICLQ 2006 TABLE OF CONTENTS 135 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 139 * All staff photos and any photos marked * in this review are © Geoffrey Sautner, and reprinted with his permission. -

Spring 2005 the Magazine of the University of Texas School of Ulaw Tlaw

Cover 4/26/05 1:07 PM Page 1 SPECIAL CONTRIBUTORS’ REPORT SPRING 2005 THE MAGAZINE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS SCHOOL OF ULAW TLAW PLUS Saying Good-bye to Bob Dawson AND Coming Home UT Law alumni Stephen to Tatum, ’79, Marcus Schwartz, Townes ’73, and Edwin DeYoung, ’71, three of the founding Hall members of the new Charles Alan Wright Society. TheWrightSociety Building Charles Alan Wright’s Legacy Through Giving THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS LAW SCHOOL FOUNDATION, 727 E. DEAN KEETON STREET, AUSTIN, TEXAS 78705 01_Contents 4/26/05 1:14 PM Page 1 CONTENTS ABLE OF SPRING 2005 T Professor Jane Stapleton, a product liability expert, joins the American Law Institute Council. See page 12. FRONT OF THE BOOK FEATURES BACK OF THE BOOK 4 IN CAMERA MAJOR GIFTS 21 ATexas knighthood and A NEW SOCIETY LAW PARTNERS AND student societies reach out 18 GIFTS OF NOTE 26 9 DEAN POWERS GIVING BY FUND 32 A Common Purpose by Bill Powers The new Charles Alan Wright Society. GIVING BY CLASS 60 by Allegra J. Young 11 CALENDAR FRIENDS OF THE SPECIAL FEATURE LAW SCHOOL 76 12 AROUND THE LAW SCHOOL THE CONTRIBUTORS’ CORPORATIONS AND Professor Bob Dawson, alumni honors, REPORT F OUNDATIONS 78 and Del Williams, ’85, is elected 20 CLOSING ARGUMENT 80 Coming Home to Townes Hall UT Law recognizes those who gave by Sofia Harber Bowden,’95 to help us succeed. Cover photograph and photograph UTLAW this page by Wyatt McSpadden VOLUME 4 • ISSUE 1 02_Masthead/Ads_R2 4/29/05 4:05 PM Page 2 UTLAW UT SCHOOL OF LAW Dean BILL POWERS, JR. -

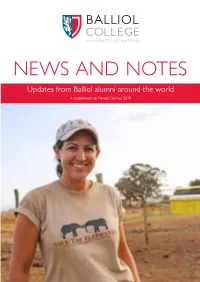

Updates from Balliol Alumni Around the World

Updates from Balliol alumni around the world A supplement to Floreat Domus 2019 News and Notes NEWS AND NOTES We are delighted to share the latest news from the Balliol community became professors at the Australian and now continuing with a life of 1940s National University here in Canberra, its own, in which more than thirty Australia. He encouraged me to learn dramatists were invited to revisit David Grove (1941) to play the recorder, as he did! the entire Shakespeare canon and At 96 the most exciting thing present versions that were completely that happens is the birth of great- intelligible to a contemporary audience grandchildren. My fifth was born in while changing as few of Shakespeare’s January to Melody Grove, actress; her 1950s original lines as possible. As expected, sister, Leila Feld, lawyer, is expecting considerable controversy followed the sixth later this year. Good to Professor Barry Cox (1950) this project in the American press, know that my genes will continue to Well, at the age of 87, it seems the but in the case of the two plays for flourish, albeit somewhat diluted. time has come to let my computer which I was responsible, both have cool down – though I hope to keep already received sumptuous, full- Hyla Holden (1942) my body warm for a few years more! A scale productions at the Alabama Rather deaf and wobbly, I continue few years ago, I published the last of Shakespeare Festival, under the to write – music and musings my research papers on the structure direction of a British-born and (neither publishable).