Also Available As an E-Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pr-Dvd-Holdings-As-Of-September-18

CALL # LOCATION TITLE AUTHOR BINGE BOX COMEDIES prmnd Comedies binge box (includes Airplane! --Ferris Bueller's Day Off --The First Wives Club --Happy Gilmore)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX CONCERTS AND MUSICIANSprmnd Concerts and musicians binge box (Includes Brad Paisley: Life Amplified Live Tour, Live from WV --Close to You: Remembering the Carpenters --John Sebastian Presents Folk Rewind: My Music --Roy Orbison and Friends: Black and White Night)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX MUSICALS prmnd Musicals binge box (includes Mamma Mia! --Moulin Rouge --Rodgers and Hammerstein's Cinderella [DVD] --West Side Story) [videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX ROMANTIC COMEDIESprmnd Romantic comedies binge box (includes Hitch --P.S. I Love You --The Wedding Date --While You Were Sleeping)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. DVD 001.942 ALI DISC 1-3 prmdv Aliens, abductions & extraordinary sightings [videorecording]. DVD 001.942 BES prmdv Best of ancient aliens [videorecording] / A&E Television Networks History executive producer, Kevin Burns. DVD 004.09 CRE prmdv The creation of the computer [videorecording] / executive producer, Bob Jaffe written and produced by Donald Sellers created by Bruce Nash History channel executive producers, Charlie Maday, Gerald W. Abrams Jaffe Productions Hearst Entertainment Television in association with the History Channel. DVD 133.3 UNE DISC 1-2 prmdv The unexplained [videorecording] / produced by Towers Productions, Inc. for A&E Network executive producer, Michael Cascio. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again [videorecording] / producers, Simon Harries [and three others] director, Ashok Prasad [and five others]. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again. Season 2 [videorecording] / director, Luc Tremoulet producer, Page Shepherd. -

1 Production Design / Art Direction

[email protected] - 0422 096 761 PRODUCTION DESIGN / ART DIRECTION WORKED ON THE FOLLOWING PROJECTS:- 2012 Robot I “Enjoy More” Samsung TVC Production Designer 2012 Foxtel “Journey Begins” TVC Production Designer 2012 Motion Picture Co “Mitsubishi Fridge” TVC Production Designer 2012 Foxtel / WTFN “The People Speak” TV Show Production Designer 2012 Channel 10 / WTFN “The Living Room” TV Show Production Designer 2012 The DMC Initiative “Westfield Premium” TVC Production Designer 2011 Foxtel Creative “Christmas Promo” TVC Production Designer 2011 Bazmark III “The Great Gatsby” Feature Film Draftsperson 2011 Jungleboys “Moonpark” Only The Sea Slugs - Film Clip Production Designer 2011 “Wasted” PopUp Restaurant - Event Designer 2011 Foxtel – Area 51 “Australian Drama” – TVC Production Designer 2011 Beyond Productions “Behind Mansion Walls” - TV Series Production Designer 2011 SeeSaw Films Art Direction of Style Book “Monkey” Commissioned by: Emile Sherman – Producers Guild of America Award Winner & Academy Award Nominee 2010 Corsan Films – “Singularity” Design Assistant Director: Roland Joffe Academy Award Winner - Production Designer: Luciana Arrighi 2010 Universal Studios - Art Direction of Style Book “Dracula Year Zero” Director: Alex Proyas / Production Designer: Roger Ford 2010 Plasma . Tactic Creative Services – Audio Post House Interior Designer 2010 Fox Searchlight Art Direction of Style Book “The Book Thief” 2010 Starchild Productions / Sony “Lying” Amy Meredith Film Clip Production Designer 2009 Walden Media & Fox Searchlight Set -

The Dead Devils of Cockle Creek by Kathryn Marquet

A COMEDY WITH THE SAFETY OFF LA BOITE AND PLAYLAB PRESENT THE DEAD DEVILS OF COCKLE CREEK BY KATHRYN MARQUET PROGRAM Image by Dylan Evans PROGRAMLA BOITE THE DEAD DEVILS OF COCKLE CREEK LA BOITE THEATRE COMPANY 1 THEATRE COMPANY La Boite Theatre Company is supported by the La Boite Theatre Company is assisted by the Australian Government Queensland Government through Arts Queensland through the Australia Council, its funding and advisory body PRESENTED BY LA BOITE THEATRE COMPANY AND PLAYLAB 10 FEBRUARY – 03 MARCH 2018 AT THE ROUNDHOUSE THEATRE ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF COUNTRY AT LA BOITE WE ACKNOWLEDGE THE COUNTRY ON WHICH WE WORK, AND THE CAST TRADITIONAL CUSTODIANS OF THIS LAND - THE TURRBAL AND JAGERA PEOPLE. WE GIVE OUR RESPECTS TO THEIR ELDERS PAST, PRESENT, AND EMERGING. MICKEY O’TOOLE ........................................................... JOHN BATCHELOR HARRIS ROBB .................................................................. JULIAN CURTIS WE HONOUR THE ABORIGINAL AND TORRES STRAIT ISLANDER PEOPLE, THE FIRST DESTINEE LEE .............................................................KIMIE TSUKAKOSHI AUSTRALIANS, WHOSE LANDS, WINDS AND WATERS WE ALL NOW SHARE, AND GEORGE TEMPLETON .............................................................EMILY WEIR THEIR ANCIENT AND ENDURING CULTURES. THIS COUNTRY WAS THE HOME OF STORY-TELLING LONG BEFORE LA BOITE EXISTED, AND WE ARE PRIVILEGED AND CREATIVES GRATEFUL TO SHARE OUR STORIES HERE TODAY. WRITER .................................................................... KATHRYN MARQUET -

Why We Oppose Autism Speaks

Why We Oppose Autism Speaks Autism Speaks, despite its name, does not speak for autistic people. When polled, 98% of autistic adults oppose Autism Speaks –and there is a massive global movement by autistic people and allies to stop Autism Speaks. In fact, regardless of the many differences among autistic advocates about politics and advocacy, there is one view we pretty much ALL agree on: that Autism Speaks is a hate group. Some reasons: Autism Speaks has allocated hundreds of millions of dollars towards “eugenics” projects that may seek to prevent autistic people from being born. • Autism Speaks is a co-founder of the MSSNG project, a massive, far-reaching project to make a global database of 10,000+ autistic children’s DNA available for use by researchers throughout the world who can fill out a pop-up menu on their website to access it. • The DNA is extracted without the children’s permission. • It is done with the purpose of identifying “autism genes” that will then be used in prenatal testing. • If common genes are identified through this research, people will do prenatal testing and terminate pregnancies if they think there are “signs of autism”. • This project is active in Canada. Autism Speaks Canada has earmarked hundreds of thousands of dollars to its own arm of the project. A group of geneticists in Toronto has also been involved in collecting data for the database. • One of the project’s co-founders, Dr. James Watson, was fired from Cold Spring Harbour Laboratory for his racist remarks about African Americans, intelligence and using eugenics to find “a cure for stupid”. -

Disability in an Age of Environmental Risk by Sarah Gibbons a Thesis

Disablement, Diversity, Deviation: Disability in an Age of Environmental Risk by Sarah Gibbons A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfillment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2016 © Sarah Gibbons 2016 I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This dissertation brings disability studies and postcolonial studies into dialogue with discourse surrounding risk in the environmental humanities. The central question that it investigates is how critics can reframe and reinterpret existing threat registers to accept and celebrate disability and embodied difference without passively accepting the social policies that produce disabling conditions. It examines the literary and rhetorical strategies of contemporary cultural works that one, promote a disability politics that aims for greater recognition of how our environmental surroundings affect human health and ability, but also two, put forward a disability politics that objects to devaluing disabled bodies by stigmatizing them as unnatural. Some of the major works under discussion in this dissertation include Marie Clements’s Burning Vision (2003), Indra Sinha’s Animal’s People (2007), Gerardine Wurzburg’s Wretches & Jabberers (2010) and Corinne Duyvis’s On the Edge of Gone (2016). The first section of this dissertation focuses on disability, illness, industry, and environmental health to consider how critics can discuss disability and environmental health in conjunction without returning to a medical model in which the term ‘disability’ often designates how closely bodies visibly conform or deviate from definitions of the normal body. -

To View a Downloadable PDF of Alex

ZAMMY SENSIBILITIES AN INTERVIEW WITH ALEX ZAMM ALEX ZAMM? THE NAME GIVES you a Alex Zamm is the director of the latest he will ever sit down. In fact it seemed hint. Could there be some kind of fantastic comedy direct to DVD/video uncomfortable for him to be still for this connection? ‘Kapow’, ‘ Boom’. feature (IG2), which interview but like everything he does, Yes … there was a ‘Zamm’ in there some- was made by Disney in Brisbane and Alex has a commitment, clarity and care where. Is Zamm his real name? It turns is due for worldwide release 11 March, that personifi es the idea of inspiring out it is and as a kid, Alex loved seeing his 2003, starring French Stewart1 as the leadership together with the rare com- name fl ashing on the screen—maybe a inimitable Gadget.2 bination of skills and talent that makes childhood incentive to see it up there one for a great comedy director. And it all day for real. Like his name, Zamm brings a level of started with his impassioned search for energy, dedication and love to his writ- what makes comedy and stories work. PRU DONOVAN ing and directing that is truly exhila- rating. He reminds you a little of the RoadRunner. When he’s moving he’s almost invisible, and when he stops, he talks very fast and just long enough Mad to ensure you have the information you need before he’s off again to re-write a scene, or rush to a mix or start a new script in the ad break, and this after two years of complete dedication and ! " immersion in the incredibly complicated visual effects movie IG2. -

Constructing Narratives and Identities in Auto/Biography About Autism

RELATIONAL REPRESENTATION: CONSTRUCTING NARRATIVES AND IDENTITIES IN AUTO/BIOGRAPHY ABOUT AUTISM by MONICA L. ORLANDO Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May 2015 2 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the dissertation of Monica Orlando candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy.* Committee Chair Kimberly Emmons Committee Member Michael Clune Committee Member William Siebenschuh Committee Member Jonathan Sadowsky Committee Member Joseph Valente Date of Defense March 3, 2015 * We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. 3 Dedications and Thanks To my husband Joe, for his patience and support throughout this graduate school journey. To my family, especially my father, who is not here to see me finish, but has always been so proud of me. To Kim Emmons, my dissertation advisor and mentor, who has been a true joy to work with over the past several years. I am very fortunate to have been guided through this project by such a supportive and encouraging person. To the graduate students and faculty of the English department, who have made my experience at Case both educational and enjoyable. I am grateful for having shared the past five years with all of them. 4 Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................... 5 Chapter 1: Introduction Relationality and the Construction of Identity in Autism Life Writing ........................ 6 Chapter 2 Clara Claiborne Park’s The Siege and Exiting Nirvana: Shifting Conceptions of Autism and Authority ................................................................................................. 53 Chapter 3 Transformative Narratives: Double Voicing and Personhood in Collaborative Life Writing about Autism .............................................................................................. -

The Joy of Autism: Part 2

However, even autistic individuals who are profoundly disabled eventually gain the ability to communicate effectively, and to learn, and to reason about their behaviour and about effective ways to exercise control over their environment, their unique individual aspects of autism that go beyond the physiology of autism and the source of the profound intrinsic disabilities will come to light. These aspects of autism involve how they think, how they feel, how they express their sensory preferences and aesthetic sensibilities, and how they experience the world around them. Those aspects of individuality must be accorded the same degree of respect and the same validity of meaning as they would be in a non autistic individual rather than be written off, as they all too often are, as the meaningless products of a monolithically bad affliction." Based on these extremes -- the disabling factors and atypical individuality, Phil says, they are more so disabling because society devalues the atypical aspects and fails to accommodate the disabling ones. That my friends, is what we are working towards -- a place where the group we seek to "help," we listen to. We do not get offended when we are corrected by the group. We are the parents. We have a duty to listen because one day, our children may be the same people correcting others tomorrow. In closing, about assumptions, I post the article written by Ann MacDonald a few days ago in the Seattle Post Intelligencer: By ANNE MCDONALD GUEST COLUMNIST Three years ago, a 6-year-old Seattle girl called Ashley, who had severe disabilities, was, at her parents' request, given a medical treatment called "growth attenuation" to prevent her growing. -

What Killed Australian Cinema & Why Is the Bloody Corpse Still Moving?

What Killed Australian Cinema & Why is the Bloody Corpse Still Moving? A Thesis Submitted By Jacob Zvi for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the Faculty of Health, Arts & Design, Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne © Jacob Zvi 2019 Swinburne University of Technology All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. II Abstract In 2004, annual Australian viewership of Australian cinema, regularly averaging below 5%, reached an all-time low of 1.3%. Considering Australia ranks among the top nations in both screens and cinema attendance per capita, and that Australians’ biggest cultural consumption is screen products and multi-media equipment, suggests that Australians love cinema, but refrain from watching their own. Why? During its golden period, 1970-1988, Australian cinema was operating under combined private and government investment, and responsible for critical and commercial successes. However, over the past thirty years, 1988-2018, due to the detrimental role of government film agencies played in binding Australian cinema to government funding, Australian films are perceived as under-developed, low budget, and depressing. Out of hundreds of films produced, and investment of billions of dollars, only a dozen managed to recoup their budget. The thesis demonstrates how ‘Australian national cinema’ discourse helped funding bodies consolidate their power. Australian filmmaking is defined by three ongoing and unresolved frictions: one external and two internal. Friction I debates Australian cinema vs. Australian audience, rejecting Australian cinema’s output, resulting in Frictions II and III, which respectively debate two industry questions: what content is produced? arthouse vs. -

Autistic Adult and Non-Autistic Parent Advocates: Bridging the Divide

AUTHORS' VERSION Rottier, H. & Gernsbacher, M. A. (2020). Autistic adult and non-autistic parent advocates: Bridging the divide. In. A. C. Carey, J. M., Ostrove, & T. Fannon (Eds.) Disability alliances and allies (Research in social science and disability, Vol. 12, pp. 155-166). Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1479-354720200000012011 Chapter 7 AUTISTIC ADULT AND NON-AUTISTIC PARENT ADVOCATES: BRIDGING THE DIVIDE Helen Rottier and Morton Ann Gernsbacher ABSTRACT Purpose: Due to the developmental nature of autism, which is often diagnosed in preschool or elementary school-aged children, non-autistic parents of autistic children typically play a prominent role in autism advocacy. How- ever, as autistic children become adults and adult diagnoses of autism continue to rise, autistic adults have played a more prominent role in advo- cacy. The purpose of this chapter is to explore the histories of adult and non-autistic parent advocacy in the United States and to examine the points of divergence and convergence. Approach: Because of their different perspectives and experiences, advocacy by autistic adults and non-autistic parents can have distinctive goals and conflicting priorities. Therefore, the approach we take in the current chapter is a collaboration between an autistic adult and a non-autistic parent, both of whom are research scholars. Findings: The authors explore the divergence of goals and discourse between autistic self-advocates and non-autistic parent advocates and offer three principles for building future -

What About… Autism Spectrum Disorder

Special Needs J Biography The One and Only Sam: A Story Explaining Idioms Temple Grandin: How the Girl who Loved Cows Special Needs Picture Books The Red Beast: Controlling Anger in Children with for Children with Asperger Syndrome or Other Embraced Autism and Changed the World/ Sy Communication Difficulties/ Aileen Stalker 2010 Montgomery 2012 Asperger’s Syndrome/ K. Al-Ghani 2009 SPECIAL NEEDS E ALG SPECIAL NEEDS E STA SPECIAL NEEDS J BIO GRANDIN What About… Autistic Planet/ Jennifer Why does Izzy Cover her Ears?: Dealing with Sensory Special Needs DVD Overload/ Jennifer Veenendall 2009 Autism Elder 2007 Embracing Play: Teaching the SPECIAL NEEDS E ELD SPECIAL NEEDS E VEE Child with Autism 2006 SPECIAL NEEDS DVD EMBR Spectrum Looking After Louis/ Lesley I have Autism, I am Awesome/ Meredith Zolty 2011 Ely 2004 SPECIAL NEEDS E ZOL Living Along the Autism Disorder SPECIAL NEEDS E ELY Spectrum: 2009 Special Needs J/Y Fiction SPECIAL NEEDS DVD LIVI Who Took My Shoe?/ Karen Emigh 2003 Anything but Typical/ Nora Raleigh Baskin 2009 SPECIAL NEEDS E EMI SPECIAL NEEDS J FICTION BAS Managing Puberty, Social Challenges and Almost A-U-T-I-S-T-I-C?: How Silly is that?: I Don’t Need Jackson Whole Wyoming/ Joan Clark 2005 Everything 2013 Any Labels at All/ Lynda Farrington Wilson 2012 SPECIAL NEEDS J FICTION CLA SPECIAL NEEDS DVD MANA SPECIAL NEEDS E FAR Mockingbird: Mok’ing-bûrd/ Kathryn Erskine 2010 Model Me Friendship: For Children with Autism, Playing by the Rules: a Story about Autism/ Dena SPECIAL NEEDS J FIC ERS Asperger Syndrome, PDD-NOS, Nonverbal Learning Fox Luchsinger 2007 Disorders, Social Anxiety, Learning Disabilities and SPECIAL NEEDS E LUC The Boy Who Ate Stars/ Kochka Delays 2007 2006 SPECIAL NEEDS DVD MODE My Brother is Autistic/ Jennifer Moore-Mallinos 2008 SPECIAL NEEDS J FICTION KOC SPECIAL NEEDS E MOO Time for a Playdate 2005 Rules/ Cynthia Lord 2006 SPECIAL NEEDS DVD MODE David’s World : a Picture Book about Living with SPECIAL NEEDS J FIC LOR Autism/ Dagmar H. -

MNC Resume Tom Mcsweeney Jan2019

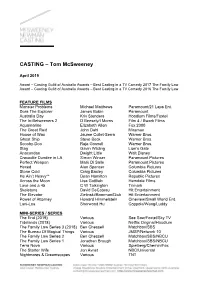

CASTING – Tom McSweeney April 2019 Award – Casting Guild of Australia Awards – Best Casting in a TV Comedy 2017 The Family Law Award – Casting Guild of Australia Awards – Best Casting in a TV Comedy 2016 The Family Law FEATURE FILMS Monster Problems Michael Matthews Paramount/21 Laps Ent. Dora The Explorer James Bobin Paramount Australia Day Kriv Stenders Hoodlum Films/Foxtel The In-Betweeners 2 D Beesely/I Morris Film 4 / Bwark Films Aquamarine Elizabeth Allen Fox 2000 The Great Raid John Dahl Miramax House of Wax Jaume Collet-Serra Warner Bros. Ghost Ship Steve Beck Warner Bros. Scooby-Doo Raja Gosnell Warner Bros. Stag Gavin Wilding Lion’s Gate Anacondas Dwight Little Walt Disney Crocodile Dundee in LA Simon Wincer Paramount Pictures Perfect Weapon Mark Di Salle Paramount Pictures Hexed Alan Spencer Columbia Pictures Stone Cold Craig Baxley Columbia Pictures He Ain’t Heavy** Dean Hamilton Republic Pictures Across the Moon Lisa Gottlieb Hemdale Films Love and a 45 C W Talkington Trimark Skeletons David DeCoteau Hit Entertainment The Elevator Zielinski/Boorman/Dick Hit Entertainment Power of Attorney Howard Himmelstein Cineview/Small World Ent. Lani-Loa Sherwood Hu Coppola/Wang/Luddy MINI-SERIES / SERIES The End (2019) Various See Saw/Foxtel/Sky TV Tidelands (2018) Various Netflix Original/Hoodlum The Family Law Series 3 (2018) Ben Chessell Matchbox/SBS The Bureau Of Magical Things Various JMSP/Network 10 The Family Law Series 2 Ben Chessell Matchbox/SBS/NBCU The Family Law Series 1 Jonathan Brough Matchbox/SBS/NBCU Terra Nova Various Spielberg/Chernin/Fox The Starter Wife Jon Avnet NBC/Universal Nightmares & Dreamscapes Various TNT Reef Doctors C.