Branching Boogaloo: Botanical Adventures in Multi-Mediated Morphologies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MCB5068 Intro

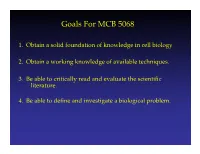

Goals For MCB 5068 1. Obtain a solid foundation of knowledge in cell biology 2. Obtain a working knowledge of available techniques. 3. Be able to critically read and evaluate the scientific literature. 4. Be able to define and investigate a biological problem. Molecular Cell Biology 5068 To Do: Visit website: www.mcb5068.wustl.edu Sign up for course. Check out Self Assessment homework under Mercer- Introduction Visit Discussion Sections: Read “Official” Instructions TA’s: 1st Session: Nana Owusu-Boaitey [email protected] 2nd Session: Shankar Parajuli [email protected] 3rd Session: Jeff Kremer [email protected] What is Cell Biology? biochemistry genetics cytology physiology Molecular Cell Biology CELL BIOLOGY/MICROSCOPE Microscope first built in 1595 by Hans and Zacharias Jensen in Holland Zacharias Jensen CELL BIOLOGY/MICROSCOPE Robert Hooke accomplished in physics, astronomy, chemistry, biology, geology, and architecture. Invented universal joint, iris diaphragm, anchor escapement & balance spring, devised equation describing elasticity (“Hooke’s Law”). In 1665 publishes Micrographia CELL BIOLOGY/MICROSCOPE Robert Hooke . “I could exceedingly plainly perceive it to be all perforated and porous, much like a Honey- comb, but that the pores of it were not regular. these pores, or cells, . were indeed the first microscopical pores I ever saw, and perhaps, that were ever seen, for I had not met with any Writer or Person, that had made any mention of them before this. .” CELL BIOLOGY/MICROSCOPE Antony van Leeuwenhoek (1632-1723) CELL BIOLOGY/MICROSCOPE Antony van Leeuwenhoek (1632-1723) a tradesman of Delft, Holland, in 1673, with no formal training, makes some of the most important discoveries in biology. -

History of the Cell Theory All Living Organisms Are Composed of Cells, and All Cells Arise from Other Cells

History of the Cell Theory All living organisms are composed of cells, and all cells arise from other cells. These simple and powerful statements form the basis of the cell theory, first formulated by a group of European biologists in the mid-1800s. So fundamental are these ideas to biology that it is easy to forget they were not always thought to be true. Early Observations The invention of the microscope allowed the first view of cells. English physicist and microscopist Robert Hooke (1635–1702) first described cells in 1665. He made thin slices of cork and likened the boxy partitions he observed to the cells (small rooms) in a monastery. The open spaces Hooke observed were empty, but he and others suggested these spaces might be used for fluid transport in living plants. He did not propose, and gave no indication that he believed, that these structures represented the basic unit of Robert Hooke's microscope. Hooke living organisms. first described cells in 1665. Marcello Malpighi (1628–1694), and Hooke's colleague, Nehemiah Grew (1641–1712), made detailed studies of plant cells and established the presence of cellular structures throughout the plant body. Grew likened the cellular spaces to the gas bubbles in rising bread and suggested they may have formed through a similar process. The presence of cells in animal tissue was demonstrated later than in plants because the thin sections needed for viewing under the microscope are more difficult to prepare for animal tissues. The prevalent view of Hooke's contemporaries was that animals were composed of several types of fibers, the various properties of which accounted for the differences among tissues. -

Microtechnique 3Rd Year Studen

1 Genetics – Theory 4th Stage Students-Biology Lec. 1 History of Genetics People have known about inheritance for a long time. Children resemble their parents. Domestication of animals and plants, selective breeding for good characteristics. Sumerian horse breeding records. Egyptian data palm breeding. Ability to identify a person as a member of a particular family by certain physical traits. (Hair, nose….etc.). The mechanisms were not readily apparent. The Greek philosophers had a variety of ideas: 1. Theophrastus proposed that male flowers caused female flowers to ripen. 2. Hippocrates speculated that "seeds" were produced by various body parts and transmitted to offspring at the time of conception. 3. Arisotle thought that male and female semen mixed at conception. 4. Aeschylus proposed the male as the parent, with the female as a "nurse for the young life sown within her". There are different old theories proposed to explain the similarities and dissimilarities between individuals: 1. Blending theory, blending theory of inheritance. The mixture of sperm and egg resulted in progeny that were a "blend" of two parents' characteristics. The blending theory means mixing between two colors (for example white and black produce a gray color, then it is very difficult to return to the original colors). the idea that individuals inherit a smooth blend of traits from their parents. Mendel's work disproved this, showing that traits are composed of combinations of distinct genes rather than a continuous blend. 2. Acquired character inheritance: Another theory that had some support at that time was the inheritance of acquired characteristics: the belief that individuals inherit traits strengthened by their parents. -

Zoology Cell Biology Definition and History

1 Subject: Zoology Cell Biology definition and History “Life is manifested only through the functioning of intact cells,,never in their absence”..Diversity in the conformational organization of the bio-molecules results in the living world with different types of cellular organisms. Cell is the basic unit of all living organism.It is the smallest part of the body of an organism which is capable of independent existence and performing the essential functions of life. • The word Cell comes from the Latin word “Cella” means “Hollow cavity” • Cell can be defined as the fundamental structural and functional unit of all living beings. • Study of cell structure is called Cytology • Study of life at cellular level is called Cell Biology. • Cell Biology deals with all aspects of cell including structure and metabolism. History of Cell Biology The invention of microscope by Hans and Zacharias Janssen in 1590 opened up a smaller world showing what living forms were composed of. • Robert Hooke first identified the compartment like structures in the cork . • Hooke (1665) observed a thin slice of cork under microscope and observed rectangular spaces which looked like small rooms inhabited by monks, hence named them as cells. 2 Fig.1.Robert Hooke Fig.2.Cork cells • His observations were published in a book called Micrographia. • However, what Hooke actually saw under the microscope was the cell walls of dead cells., Hooke did not know their real structure or function. • The first man to witness a live cell under a microscope was Antony van Leeuwenhoek (1674). • He observed many microscopic organisms like protozoans, bacteria, algae and sperms and described them as animalcules. -

Cell Theory 1 Cell Theory

Cell theory 1 Cell theory Cell theory refers to the idea that cells are the basic unit of structure in every living thing. Development of this theory during the mid 17th century was made possible by advances in microscopy. This theory is one of the foundations of biology. The theory says that new cells are formed from other existing cells, and that the cell is a fundamental unit of structure, function and organization in all living organisms. A prokaryote Cell theory 2 History The cell was discovered by Robert Hooke in 1665. He examined (under a coarse, compound microscope) very thin slices of cork and saw a multitude of tiny pores that he remarked looked like the walled compartments of a honeycomb. Because of this association, Hooke called them cells, the name they still bear. However, Hooke did not know their real structure or function.[1] Hooke's description of these cells (which were actually non-living cell walls) was published in Micrographia.[2] . His cell observations gave no indication of the nucleus and other organelles found in most living cells. The first man to witness a live cell under a microscope was Antony van Leeuwenhoek (although the first man to make a compound microscope was Zacharias Janssen), who in 1674 described the algae Spirogyra and named the moving organisms animalcules, meaning "little animals".[3] . Leeuwenhoek probably also saw bacteria.[4] Cell theory was in contrast to the vitalism theories proposed before the discovery of cells. The idea that cells were separable into individual units Drawing of the structure of cork by Robert Hooke that appeared in was proposed by Ludolph Christian Treviranus[5] and Micrographia Johann Jacob Paul Moldenhawer[6] . -

History of the 19Th Century Cell Theory in the Light of Philip Kitcher's Theory of Unification

HISTORY OF THE 19TH CENTURY CELL THEORY IN THE LIGHT OF PHILIP KITCHER'S THEORY OF UNIFICATION A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY ŞAHİN ALP TAŞKAYA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THE DEPARTMENT OF PHILOSOPHY JANUARY 2013 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Prof. Dr. Meliha Altunışık Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts Prof. Dr. Ahmet İnam Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts Assoc. Prof Samet Bağçe Supervisor Examining Committee Members Assoc. Prof. Barış Parkan (METU,PHIL) Assoc. Prof. Samet Bağçe (METU,PHIL) Assoc. Prof. Erdoğan Yıldırım (METU,SOC) PLAGIARISM I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name : Signature : iii ABSTRACT HISTORY OF THE 19TH CENTURY CELL THEORY IN THE LIGHT OF PHILIP KITCHER'S THEORY OF UNIFICATION Taşkaya, Şahin Alp M.A., Graduate School of Social Sciences Supervisor: Assoc. Prof. Samet Bağçe January 2013, 47 pages In the turn of 19th century, Biology as a scientific discipline emerged; focused on every aspect of organisms, there was no consensus on the basic entity where the observed phenomena stemmed from. -

37 the )Istory of the Germ Theory of Disease

37 5IF)JTUPSZPGUIF(FSN5IFPSZPG%JTFBTF icrobes, just like the ones you observed in Activity 36, “Looking M for Signs of Micro-Life,” were discovered in the late 1600s. But the Y idea that such tiny organisms could cause disease did not develop until the R A O L E P L 1860s, less than 150 years ago. Why did it take so long to "gure this out? CHALLENGE How did the germ theory of disease develop? MATERIALS For each group of four students miscellaneous props For each student 1 Student Sheet 37.2, “Timeline of the Germ Theory of Disease” PROCEDURE 1. Your group will be assigned one of the sections under “Cast of Characters.” 2. With your group, read the section carefully and identify the important contribution(s) to science made by your character(s). Record these in your science notebook. 3. Develop a skit to present these important points to your class. You can make your skit historical (for example, show how your scientist made the discovery) or modern (for example, create an ad to sell Hooke’s book). Be sure to create a role for each person in your group. 4. Collect any props or additional materials you require. 5. Present your skit to the class. 6. As you watch the various skits, complete the timeline on Student Sheet 37.2, “Timeline of the Germ Theory of Disease.” C-30 5IF)JTUPSZPGUIF(FSN5IFPSZPG%JTFBTF t Activity 37 CAST OF CHARACTERS Robert Hooke (1635–1703) The late 17th century was a period of great scienti!c discovery. While many people offered theories without experi- mentation or evidence, English scientist Robert Hooke believed that good science resulted from making obser- vations on what you could see. -

Sugar Cube Plant Cell Can You Create a Plant Cell and Label All the Major Organelles?

Sugar Cube Plant Cell Can you create a plant cell and label all the major organelles? Do the Experiment! MATERIALS 1. Glue sugar cubes onto a piece of 5x7 chipboard or cardboard so that they resemble the shape of a plant cell. Use the plant cell diagram to help you figure out the shape. 2. Use your permanent markers to draw the different organelles onto the sugar cubes. Don’t forget the cell wall. Sugar Cubes 3. On an address label write the name of a particular Glue organelle. On a second address label write what the Permanent Markers function of that organelle is. Your cell diagram will have Pencils this information. Make sure you do this step for all the 5x7 Chip Board organelles. Toothpicks 4. Stick each organelle and its function to different Address Labels toothpicks so that they look like little flags. Push the Plant Cell Diagram organelle flags into the sugar cube where you drew that organelle. 5. Don’t eat your sugar cube masterpiece—glue tastes gross. Tell everyone that sees your model how a plant cell functions! Botany © 2020 The Children’s Museum of Houston Institute for Family Learning. DID YOU KNOW... Cells are the basic units of all KNOWN living organisms. Cells are the smallest unit of life that can reproduce independently and are often referred to as the building blocks of life. Robert Hooke discovered cells in 1665, and Matthias Jakob Schleiden and Theodor Schwann developed cell theory in 1839. You just made a plant cell out of sugar cubes. Plant cells and animal cells have some similarities, but are very different. -

The History of Biology and Its Importance for Gender Studies

Instructions for authors, subscriptions and further details: http://generos.hipatiapress.com The History of Biology and its Importance for Gender Studies Yusuke Kaneko1 1) Meiji University, Japan Date of publication: June 25th, 2016 Edition period: June 2016 – October 2016 To cite this article: Kaneko, Y. (2016). The History of Biology and its Importance for Gender Studies. Multidisciplinary Journal of Gender Studies, 5(2), 1039-1067. doi: 10.4471/generos.2016.1537 To link this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.4471/generos.2016.1537 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE The terms and conditions of use are related to the Open Journal System and to Creative Commons Attribution License (CC-BY). GÉNEROS –Multidisciplinary Journal of Gender Studies Vol. 5 No. 2 June 2016 pp. 1039-1067 The History of Biology and its Importance for Gender Studies1 Yusuke Kaneko Meiji University Abstract The aim of this paper is to call the attention, especially that of feminists, to the current progress in biology. It appears gender studies still confine themselves to outdated ideas of sex chromosomes like XX, XY (§10). However, science has been making progress. It no longer sticks to such matters as XX, XY. Its interest is now in Sry, a kind of gene (§11), and MIS, a kind of sex hormone (§14). Abnormalities of sex chromosomes are no longer evidence to deny the biological approaches, for example. We shed light on this fact, putting gender studies in the context of chronologies of science as well (§§2-9). Keywords: Gender studies, chronology of science, sex chromosomes, Sry, sex hormones 2016 Hipatia Press ISSN: 2014-3613 doi: 10.4471/generos.2016.1537 GÉNEROS –Multidisciplinary Journal of Gender Studies Vol. -

Und Seine Korrespondenz Mit Carl Friedrich Philipp Von Martius (1794-1868)

Adalbert Carl Friedrich Hellwig Schnizlein (1814-1868) und seine Korrespondenz mit Carl Friedrich Philipp von Martius (1794-1868) Aus dem Institut für Geschichte und Ethik der Medizin Der Medizinischen Fakultät der Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades Dr. med. vorgelegt von Carl Friedrich Christoph Kißlinger aus Rothenburg Als Dissertation genehmigt von der Medizinischen Fakultät der Friedrich-Alexander-Universität Erlangen-Nürnberg Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 16.04.2019 Vorsitzender des Promotionsorgans: Prof. Dr. Dr. h.c. Jürgen Schüttler Gutachter/in: Prof. Dr. Fritz Dross Prof. Dr. Renate Wittern-Sterzel Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Zusammenfassung ................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Summary ........................................................................................................ 4 2 Einleitung ............................................................................................................... 7 3 Die Korrespondenten .......................................................................................... 13 3.1 Adalbert Schnizlein (1814-1868) ................................................................. 14 3.2 Carl Friedrich Philipp von Martius (1794-1868) ......................................... 22 4 Briefkultur im 18./19. Jahrhundert ................................................................... 29 4.1 Korrespondenz:1843-1868 .......................................................................... -

The Tragic Sense of Life

the tragic sense of life CC4617.indb4617.indb i 11/7/08/7/08 11:32:22:32:22 PPMM Ernst Haeckel (seated) and his assistant Nikolai Miklucho on the way to the Canary Islands in 1866. Haeckel had just visited Darwin in the village of Downe. (Courtesy of Ernst-Haeckel-Haus, Jena.) CC4617.indb4617.indb iiii 11/7/08/7/08 11:32:22:32:22 PPMM G the tragic sense of life Ernst Haeckel and the Struggle over Evolutionary Thought robert j. richards the university of chicago press chicago and london CC4617.indb4617.indb iiiiii 11/7/08/7/08 11:32:22:32:22 PPMM for my colleagues and students at the university of chicago CC4617.indb4617.indb v 11/7/08/7/08 11:32:23:32:23 PPMM CC4617.indb4617.indb vvii 11/7/08/7/08 11:32:23:32:23 PPMM G contents List of Illustrations 000 Preface 000 1. Introduction 000 The Tragic Source of the Anti-Religious Character of Evolutionary Theory 000 2. Formation of a Romantic Biologist 000 Early Student Years 000 University Years 000 Habilitation and Engagement 000 3. Research in Italy and Conversion to Darwinism 000 Friendship with Allmers and Temptations of the Bohemian Life 000 Radiolarians and the Darwinian Explanation 000 Appendix: Haeckel’s Challenger Investigations 000 4. Triumph and Tragedy at Jena 000 Habilitation and Teaching 000 Friendship with Gegenbaur 000 For Love of Anna 000 The Defender of Darwin 000 Tragedy in Jena 000 vii CC4617.indb4617.indb vviiii 11/7/08/7/08 11:32:23:32:23 PPMM viii contents 5. -

HUNTIA a Journal of Botanical History

HUNTIA A Journal of Botanical History VOLUME 15 NUMBER 2 2015 Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation Carnegie Mellon University Pittsburgh The Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation, a research division of Carnegie Mellon University, specializes in the history of botany and all aspects of plant science and serves the international scientific community through research and documentation. To this end, the Institute acquires and maintains authoritative collections of books, plant images, manuscripts, portraits and data files, and provides publications and other modes of information service. The Institute meets the reference needs of botanists, biologists, historians, conservationists, librarians, bibliographers and the public at large, especially those concerned with any aspect of the North American flora. Huntia publishes articles on all aspects of the history of botany, including exploration, art, literature, biography, iconography and bibliography. The journal is published irregularly in one or more numbers per volume of approximately 200 pages by the Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation. External contributions to Huntia are welcomed. Page charges have been eliminated. All manuscripts are subject to external peer review. Before submitting manuscripts for consideration, please review the “Guidelines for Contributors” on our Web site. Direct editorial correspondence to the Editor. Send books for announcement or review to the Book Reviews and Announcements Editor. Subscription rates per volume for 2015 (includes shipping): U.S. $65.00; international $75.00. Send orders for subscriptions and back issues to the Institute. All issues are available as PDFs on our Web site, with the current issue added when that volume is completed. Hunt Institute Associates may elect to receive Huntia as a benefit of membership; contact the Institute for more information.