The Tragic Sense of Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proceedings of the Seventh European Conference on Echinoderms, Göttingen, Germany, 2–9 October 2010

Zoosymposia 7: vii–ix (2012) ISSN 1178-9905 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zoosymposia/ ZOOSYMPOSIA Copyright © 2012 · Magnolia Press ISSN 1178-9913 (online edition) Preface—7th European Conference on Echinoderms MIKE REICH1,2 & JOACHIM REITNER1,2,3 1 Georg-August University of Göttingen, Geoscience Museum & Geopark, Göttingen, Germany; E-mail: [email protected] 2 Georg-August University of Göttingen, Geoscience Centre, Department of Geobiology, Göttingen, Germany 3 Georg-August University of Göttingen, Courant Research Centre Geobiology, Göttingen, Germany *In: Kroh, A. & Reich, M. (Eds.) Echinoderm Research 2010: Proceedings of the Seventh European Conference on Echinoderms, Göttingen, Germany, 2–9 October 2010. Zoosymposia, 7, xii + 316 pp. Since the pioneering meeting in 1979 in Brussels, the European echinoderm community has cele- brated advances in echinoderm science, biology and palaeontology in what has now become a regular conference series (see Ziegler & Kroh 2012, p. 1–24 of this volume). This reflects the interest of the scientific community in the multidisciplinary field of echinoderm research between biology, palae- ontology, physiology, fisheries, aquaculture, medicine and others. The 7th European Conference on Echinoderms (ECE) was held on October 2–9, 2010 (Fig. 1) in Germany, and was hosted by the Georg-August University of Göttingen. The Göttingen University has a long tradition in echinoderm research. A vast number of naturalists, zoologists, palaeontologists, and collectors, like Pehr Forsskål (1732–1769), Peter Simon -

Download (580Kb)

Manuscript version: Author’s Accepted Manuscript The version presented in WRAP is the author’s accepted manuscript and may differ from the published version or Version of Record. Persistent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/113725 How to cite: Please refer to published version for the most recent bibliographic citation information. If a published version is known of, the repository item page linked to above, will contain details on accessing it. Copyright and reuse: The Warwick Research Archive Portal (WRAP) makes this work by researchers of the University of Warwick available open access under the following conditions. Copyright © and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable the material made available in WRAP has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. Publisher’s statement: Please refer to the repository item page, publisher’s statement section, for further information. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected]. warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications Systematicity in Kant’s third Critique Andrew Cooper – [email protected] Penultimate draft – please refer to published version: https://www.pdcnet.org/idstudies/content/idstudies_2019_0999_1_14_83 Idealistic Studies 47(3), 2019 Abstract: Kant’s Critique of the Power of Judgment is often interpreted in light of its initial reception. -

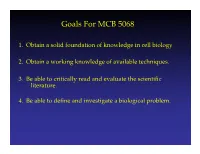

MCB5068 Intro

Goals For MCB 5068 1. Obtain a solid foundation of knowledge in cell biology 2. Obtain a working knowledge of available techniques. 3. Be able to critically read and evaluate the scientific literature. 4. Be able to define and investigate a biological problem. Molecular Cell Biology 5068 To Do: Visit website: www.mcb5068.wustl.edu Sign up for course. Check out Self Assessment homework under Mercer- Introduction Visit Discussion Sections: Read “Official” Instructions TA’s: 1st Session: Nana Owusu-Boaitey [email protected] 2nd Session: Shankar Parajuli [email protected] 3rd Session: Jeff Kremer [email protected] What is Cell Biology? biochemistry genetics cytology physiology Molecular Cell Biology CELL BIOLOGY/MICROSCOPE Microscope first built in 1595 by Hans and Zacharias Jensen in Holland Zacharias Jensen CELL BIOLOGY/MICROSCOPE Robert Hooke accomplished in physics, astronomy, chemistry, biology, geology, and architecture. Invented universal joint, iris diaphragm, anchor escapement & balance spring, devised equation describing elasticity (“Hooke’s Law”). In 1665 publishes Micrographia CELL BIOLOGY/MICROSCOPE Robert Hooke . “I could exceedingly plainly perceive it to be all perforated and porous, much like a Honey- comb, but that the pores of it were not regular. these pores, or cells, . were indeed the first microscopical pores I ever saw, and perhaps, that were ever seen, for I had not met with any Writer or Person, that had made any mention of them before this. .” CELL BIOLOGY/MICROSCOPE Antony van Leeuwenhoek (1632-1723) CELL BIOLOGY/MICROSCOPE Antony van Leeuwenhoek (1632-1723) a tradesman of Delft, Holland, in 1673, with no formal training, makes some of the most important discoveries in biology. -

History of the Cell Theory All Living Organisms Are Composed of Cells, and All Cells Arise from Other Cells

History of the Cell Theory All living organisms are composed of cells, and all cells arise from other cells. These simple and powerful statements form the basis of the cell theory, first formulated by a group of European biologists in the mid-1800s. So fundamental are these ideas to biology that it is easy to forget they were not always thought to be true. Early Observations The invention of the microscope allowed the first view of cells. English physicist and microscopist Robert Hooke (1635–1702) first described cells in 1665. He made thin slices of cork and likened the boxy partitions he observed to the cells (small rooms) in a monastery. The open spaces Hooke observed were empty, but he and others suggested these spaces might be used for fluid transport in living plants. He did not propose, and gave no indication that he believed, that these structures represented the basic unit of Robert Hooke's microscope. Hooke living organisms. first described cells in 1665. Marcello Malpighi (1628–1694), and Hooke's colleague, Nehemiah Grew (1641–1712), made detailed studies of plant cells and established the presence of cellular structures throughout the plant body. Grew likened the cellular spaces to the gas bubbles in rising bread and suggested they may have formed through a similar process. The presence of cells in animal tissue was demonstrated later than in plants because the thin sections needed for viewing under the microscope are more difficult to prepare for animal tissues. The prevalent view of Hooke's contemporaries was that animals were composed of several types of fibers, the various properties of which accounted for the differences among tissues. -

Copyrighted Material

Chapter 1 History Systematics has its origins in two threads of biological science: classification and evolution. The organization of natural variation into sets, groups, and hierarchies traces its roots to Aristotle and evolution to Darwin. Put simply, systematization of nature can and has progressed in absence of causative theories relying on ideas of “plan of nature,” divine or otherwise. Evolutionists (Darwin, Wallace, and others) proposed a rationale for these patterns. This mixture is the foundation of modern systematics. Originally, systematics was natural history. Today we think of systematics as being a more inclusive term, encompassing field collection, empirical compar- ative biology, and theory. To begin with, however, taxonomy, now known as the process of naming species and higher taxa in a coherent, hypothesis-based, and regular way, and systematics were equivalent. Roman bust of Aristotle (384–322 BCE) 1.1 Aristotle Systematics as classification (or taxonomy) draws its Western origins from Aris- totle1. A student of Plato at the Academy and reputed teacher of Alexander the Great, Aristotle founded the Lyceum in Athens, writing on a broad variety of topics including what we now call biology. To Aristotle, living things (species) came from nature as did other physical classes (e.g. gold or lead). Today, we refer to his classification of living things (Aristotle, 350 BCE) that show simi- larities with the sorts of classifications we create now. In short, there are three featuresCOPYRIGHTED of his methodology that weMATERIAL recognize immediately: it was functional, binary, and empirical. Aristotle’s classification divided animals (his work on plants is lost) using Ibn Rushd (Averroes) functional features as opposed to those of habitat or anatomical differences: “Of (1126–1198) land animals some are furnished with wings, such as birds and bees.” Although he recognized these features as different in aspect, they are identical in use. -

Ernst Haeckel's Embryological Illustrations

Pictures of Evolution and Charges of Fraud Ernst Haeckel’s Embryological Illustrations By Nick Hopwood* ABSTRACT Comparative illustrations of vertebrate embryos by the leading nineteenth-century Dar- winist Ernst Haeckel have been both highly contested and canonical. Though the target of repeated fraud charges since 1868, the pictures were widely reproduced in textbooks through the twentieth century. Concentrating on their first ten years, this essay uses the accusations to shed light on the novelty of Haeckel’s visual argumentation and to explore how images come to count as proper representations or illegitimate schematics as they cross between the esoteric and exoteric circles of science. It exploits previously unused manuscripts to reconstruct the drawing, printing, and publishing of the illustrations that attracted the first and most influential attack, compares these procedures to standard prac- tice, and highlights their originality. It then explains why, though Haeckel was soon ac- cused, controversy ignited only seven years later, after he aligned a disciplinary struggle over embryology with a major confrontation between liberal nationalism and Catholicism—and why the contested pictures nevertheless survived. INETEENTH-CENTURY IMAGES OF EVOLUTION powerfully and controversially N shape our view of the world. In 1997 a British developmental biologist accused the * Department of History and Philosophy of Science, University of Cambridge, Free School Lane, Cambridge CB2 3RH, United Kingdom. Research for this essay was supported by the Wellcome Trust and partly carried out in the departments of Lorraine Daston and Hans-Jo¨rg Rheinberger at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science. My greatest debt is to the archivists of the Ernst-Haeckel-Haus, Jena: the late Erika Krauße gave generous help and invaluable advice over many years, and Thomas Bach, her successor as Kustos, provided much assistance with this project. -

Microtechnique 3Rd Year Studen

1 Genetics – Theory 4th Stage Students-Biology Lec. 1 History of Genetics People have known about inheritance for a long time. Children resemble their parents. Domestication of animals and plants, selective breeding for good characteristics. Sumerian horse breeding records. Egyptian data palm breeding. Ability to identify a person as a member of a particular family by certain physical traits. (Hair, nose….etc.). The mechanisms were not readily apparent. The Greek philosophers had a variety of ideas: 1. Theophrastus proposed that male flowers caused female flowers to ripen. 2. Hippocrates speculated that "seeds" were produced by various body parts and transmitted to offspring at the time of conception. 3. Arisotle thought that male and female semen mixed at conception. 4. Aeschylus proposed the male as the parent, with the female as a "nurse for the young life sown within her". There are different old theories proposed to explain the similarities and dissimilarities between individuals: 1. Blending theory, blending theory of inheritance. The mixture of sperm and egg resulted in progeny that were a "blend" of two parents' characteristics. The blending theory means mixing between two colors (for example white and black produce a gray color, then it is very difficult to return to the original colors). the idea that individuals inherit a smooth blend of traits from their parents. Mendel's work disproved this, showing that traits are composed of combinations of distinct genes rather than a continuous blend. 2. Acquired character inheritance: Another theory that had some support at that time was the inheritance of acquired characteristics: the belief that individuals inherit traits strengthened by their parents. -

Zoology Cell Biology Definition and History

1 Subject: Zoology Cell Biology definition and History “Life is manifested only through the functioning of intact cells,,never in their absence”..Diversity in the conformational organization of the bio-molecules results in the living world with different types of cellular organisms. Cell is the basic unit of all living organism.It is the smallest part of the body of an organism which is capable of independent existence and performing the essential functions of life. • The word Cell comes from the Latin word “Cella” means “Hollow cavity” • Cell can be defined as the fundamental structural and functional unit of all living beings. • Study of cell structure is called Cytology • Study of life at cellular level is called Cell Biology. • Cell Biology deals with all aspects of cell including structure and metabolism. History of Cell Biology The invention of microscope by Hans and Zacharias Janssen in 1590 opened up a smaller world showing what living forms were composed of. • Robert Hooke first identified the compartment like structures in the cork . • Hooke (1665) observed a thin slice of cork under microscope and observed rectangular spaces which looked like small rooms inhabited by monks, hence named them as cells. 2 Fig.1.Robert Hooke Fig.2.Cork cells • His observations were published in a book called Micrographia. • However, what Hooke actually saw under the microscope was the cell walls of dead cells., Hooke did not know their real structure or function. • The first man to witness a live cell under a microscope was Antony van Leeuwenhoek (1674). • He observed many microscopic organisms like protozoans, bacteria, algae and sperms and described them as animalcules. -

Cell Theory 1 Cell Theory

Cell theory 1 Cell theory Cell theory refers to the idea that cells are the basic unit of structure in every living thing. Development of this theory during the mid 17th century was made possible by advances in microscopy. This theory is one of the foundations of biology. The theory says that new cells are formed from other existing cells, and that the cell is a fundamental unit of structure, function and organization in all living organisms. A prokaryote Cell theory 2 History The cell was discovered by Robert Hooke in 1665. He examined (under a coarse, compound microscope) very thin slices of cork and saw a multitude of tiny pores that he remarked looked like the walled compartments of a honeycomb. Because of this association, Hooke called them cells, the name they still bear. However, Hooke did not know their real structure or function.[1] Hooke's description of these cells (which were actually non-living cell walls) was published in Micrographia.[2] . His cell observations gave no indication of the nucleus and other organelles found in most living cells. The first man to witness a live cell under a microscope was Antony van Leeuwenhoek (although the first man to make a compound microscope was Zacharias Janssen), who in 1674 described the algae Spirogyra and named the moving organisms animalcules, meaning "little animals".[3] . Leeuwenhoek probably also saw bacteria.[4] Cell theory was in contrast to the vitalism theories proposed before the discovery of cells. The idea that cells were separable into individual units Drawing of the structure of cork by Robert Hooke that appeared in was proposed by Ludolph Christian Treviranus[5] and Micrographia Johann Jacob Paul Moldenhawer[6] . -

History of the 19Th Century Cell Theory in the Light of Philip Kitcher's Theory of Unification

HISTORY OF THE 19TH CENTURY CELL THEORY IN THE LIGHT OF PHILIP KITCHER'S THEORY OF UNIFICATION A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY ŞAHİN ALP TAŞKAYA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN THE DEPARTMENT OF PHILOSOPHY JANUARY 2013 Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences Prof. Dr. Meliha Altunışık Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts Prof. Dr. Ahmet İnam Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts Assoc. Prof Samet Bağçe Supervisor Examining Committee Members Assoc. Prof. Barış Parkan (METU,PHIL) Assoc. Prof. Samet Bağçe (METU,PHIL) Assoc. Prof. Erdoğan Yıldırım (METU,SOC) PLAGIARISM I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last name : Signature : iii ABSTRACT HISTORY OF THE 19TH CENTURY CELL THEORY IN THE LIGHT OF PHILIP KITCHER'S THEORY OF UNIFICATION Taşkaya, Şahin Alp M.A., Graduate School of Social Sciences Supervisor: Assoc. Prof. Samet Bağçe January 2013, 47 pages In the turn of 19th century, Biology as a scientific discipline emerged; focused on every aspect of organisms, there was no consensus on the basic entity where the observed phenomena stemmed from. -

Thomas Henry Huxley: the War Between Science and Religion Author(S): Sheridan Gilley and Ann Loades Source: the Journal of Religion , Jul., 1981, Vol

Thomas Henry Huxley: The War between Science and Religion Author(s): Sheridan Gilley and Ann Loades Source: The Journal of Religion , Jul., 1981, Vol. 61, No. 3 (Jul., 1981), pp. 285-308 Published by: The University of Chicago Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1202815 REFERENCES Linked references are available on JSTOR for this article: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1202815?seq=1&cid=pdf- reference#references_tab_contents You may need to log in to JSTOR to access the linked references. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at https://about.jstor.org/terms The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Religion This content downloaded from 140.160.244.146 on Wed, 24 Mar 2021 03:52:12 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms Thomas Henry Huxley: The War between Science and Religion Sheridan Gilley and Ann Loades / University of Durham Viewers of the recent BBC television series, "The Voyage of Charles Darwin,"1 must have been amused at the portrayal of Samuel Wilberforce, bishop of Oxford, at the famous meeting of the British Association at Oxford in 1860, where Wilberforce condemned the evolutionary doctrine of Darwin's Origin of Species. -

The Growth of Botanical Science in Nineteenth Century St

University of Missouri, St. Louis IRL @ UMSL Theses Graduate Works 3-20-2013 Order Out of Chaos: The Growth of Botanical Science in Nineteenth Century St. Louis Nuala F. Caomhánach University of Missouri-St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: http://irl.umsl.edu/thesis Recommended Citation Caomhánach, Nuala F., "Order Out of Chaos: The Growth of Botanical Science in Nineteenth Century St. Louis" (2013). Theses. 173. http://irl.umsl.edu/thesis/173 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Works at IRL @ UMSL. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of IRL @ UMSL. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Order Out of Chaos: The Growth of Botanical Science in Nineteenth Century St. Louis. Nuala F. Caomhánach M.A., History Department, University of Missouri–St. Louis, 2013 A Thesis Submitted to The Graduate School at the University of Missouri–St. Louis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in History May 2013 Advisory Committee Professor John Gillingham Chairperson Professor Steven Rowan Dr. Peter Raven Copyright, Nuala F. Caomhánach, 2013 Contents Abstract 3 Acknowledgements 4 Preface 7 Chapter 1. Introduction 11 Chapter 2. Order Out of Chaos 26 Chapter 3. Comprehending Minds 41 Chapter 4. As the Third City Ought To 56 Chapter 5. The Mississippian Kew 70 Chapter 6. Epilogue 83 Bibliography 87 2 Abstract Order out of Chaos: The Growth of Botanical Science in Nineteenth Century St. Louis This thesis places the botanical community in nineteenth century St. Louis back in the centre of the development of botanical science in the United States.