From Dawn to Decadence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Right to Peace, Which Occurred on 19 December 2016 by a Majority of Its Member States

In July 2016, the Human Rights Council (HRC) of the United Nations in Geneva recommended to the General Assembly (UNGA) to adopt a Declaration on the Right to Peace, which occurred on 19 December 2016 by a majority of its Member States. The Declaration on the Right to Peace invites all stakeholders to C. Guillermet D. Fernández M. Bosé guide themselves in their activities by recognizing the great importance of practicing tolerance, dialogue, cooperation and solidarity among all peoples and nations of the world as a means to promote peace. To reach this end, the Declaration states that present generations should ensure that both they and future generations learn to live together in peace with the highest aspiration of sparing future generations the scourge of war. Mr. Federico Mayor This book proposes the right to enjoy peace, human rights and development as a means to reinforce the linkage between the three main pillars of the United Nations. Since the right to life is massively violated in a context of war and armed conflict, the international community elaborated this fundamental right in the 2016 Declaration on the Right to Peace in connection to these latter notions in order to improve the conditions of life of humankind. Ambassador Christian Guillermet Fernandez - Dr. David The Right to Peace: Fernandez Puyana Past, Present and Future The Right to Peace: Past, Present and Future, demonstrates the advances in the debate of this topic, the challenges to delving deeper into some of its aspects, but also the great hopes of strengthening the path towards achieving Peace. -

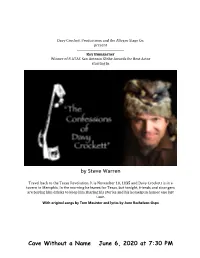

Cave Without a Name June 6, 2020 at 7:30 PM

Davy Crockett Productions and the Allegro Stage Co. present Roy Bumgarner Winner of 8 ATAC San Antonio Globe Awards for Best Actor starring in by Steve Warren Travel back to the Texas Revolution. It is November 10, 1835 and Davy Crockett is in a tavern in Memphis. In the morning he leaves for Texas, but tonight, friends and strangers are buying him drinks to keep him sharing his stories and his homespun humor one last time. With original songs by Tom Masinter and lyrics by June Rachelson-Ospa Cave Without a Name June 6, 2020 at 7:30 PM Roy Bumgarner (Davy Crockett) Roy is one of San Antonio’s favorite and most versatile lead actors. He has performed on nearly every theater stage in town, including The Majestic Theatre with San Antonio Symphony. He is loved for his roles in Jane Eyre (Rochester), Annie (Daddy Warbucks), Sweeny Todd (Sweeney), The King & I (King), My Fair Lady (Higgins), Evita (Che), Camelot (Arthur), West Side Story (Tony), Titantic (Andrews), Lend Me a Tenor (Max), Chicago (Billy), Into the Woods (Wolf, Cinderella’s Prince), Jekyll & Hyde (Jekyll/Hyde), The Crucible (John Proctor), Noises Off (Gary), Urinetown (Officer Lockston), Visiting Mr. Green (Ross), The Mystery of Edwin Drood (Jasper), Taming of the Shrew (Petrucchio), The Lion in Winter (Richard), State Fair (Pat Gilbert), The Pajama Game (Sid), Godspell (Jesus), Crazy For You, Some Like it Hot, Forever Plaid, Vexed, Forbidden Broadway and more. He has created lead rosles in the following original musicals: Gone to Texas (Bowie), Fire on the Bayou (Eduardo), Roads Courageous (Brinkley), and High Hair & Jalapenos. -

World Book Night 2016 | University of Essex

09/29/21 World Book Night 2016 | University of Essex World Book Night 2016 View Online A list of books you might like to try reading for fun - they're all in stock at the Albert Sloman Library! 197 items General Fiction (48 items) Contemporary authors (18 items) Life after life - Kate Atkinson, 2013 Book | Costa Book Award winner 2013. "During a snowstorm in England in 1910, a baby is born and dies before she can take her first breath. During a snowstorm in England in 1910, the same baby is born and lives to tell the tale. What if there were second chances? And third chances? In fact an infinite number of chances to live your life? Would you eventually be able to save the world from its own inevitable destiny? And would you even want to? Life After Life follows Ursula Todd as she lives through the turbulent events of the last century again and again. With wit and compassion, Kate Atkinson finds warmth even in life’s bleakest moments, and shows an extraordinary ability to evoke the past. Here she is at her most profound and inventive, in a novel that celebrates the best and worst of ourselves." (Review/summary from Amazon) House of leaves - Mark Z. Danielewski, 2001 Book | Horror/Romance/Postmodern. "Johnny Truant, a wild and troubled sometime employee in a LA tattoo parlour, finds a notebook kept by Zampano', a reclusive old man found dead in a cluttered apartment. Herein is the heavily annotated story of the Navidson Report. Will Navidson, a photojournalist, and his family move into a new house. -

A Book of Jewish Thoughts Selected and Arranged by the Chief Rabbi (Dr

GIFT OF Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/bookofjewishthouOOhertrich A BOOK OF JEWISH THOUGHTS \f A BOOK OF JEWISH THOUGHTS SELECTED AND ARRANGED BY THE CHIEF EABBI (DR. J. H. HERTZ) n Second Impression HUMPHREY MILFORD OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON EDINBURGH GLASGOW COPENHAGEN NEW YORK TORONTO MELBOURNE CAPE TOWN BOMBAY CALCUTTA MADRAS SHANGHAI PEKING 5681—1921 TO THE SACRED MEMORY OF THE SONS OF ISRAEL WHO FELL IN THE GREAT WAR 1914-1918 44S736 PREFATORY NOTE THIS Book of Jewish Thoughts brings the message of Judaism together with memories of Jewish martyrdom and spiritual achievement throughout the ages. Its first part, ^I am an Hebrew \ covers the more important aspects of the life and consciousness of the Jew. The second, ^ The People of the Book \ deals with IsraeFs religious contribution to mankind, and touches upon some epochal events in IsraeFs story. In the third, ' The Testimony of the Nations \ will be found some striking tributes to Jews and Judaism from non-Jewish sources. The fourth pai-t, ^ The Voice of Prayer ', surveys the Sacred Occasions of the Jewish Year, and takes note of their echoes in the Liturgy. The fifth and concluding part, ^The Voice of Wisdom \ is, in the main, a collection of the deep sayings of the Jewish sages on the ultimate problems of Life and the Hereafter. The nucleus from which this Jewish anthology gradually developed was produced three years ago for the use of Jewish sailors and soldiers. To many of them, I have been assured, it came as a re-discovery of the imperishable wealth of Israel's heritage ; while viii PREFATORY NOTE to the non-Jew into whose hands it fell it was a striking revelation of Jewish ideals and teachings. -

Excessive Use of Force by the Police Against Black Americans in the United States

Inter-American Commission on Human Rights Written Submission in Support of the Thematic Hearing on Excessive Use of Force by the Police against Black Americans in the United States Original Submission: October 23, 2015 Updated: February 12, 2016 156th Ordinary Period of Sessions Written Submission Prepared by Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights Global Justice Clinic, New York University School of Law International Human Rights Law Clinic, University of Virginia School of Law Justin Hansford, St. Louis University School of Law Page 1 of 112 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary & Recommendations ................................................................................................................................... 4 I. Pervasive and Disproportionate Police Violence against Black Americans ..................................................................... 21 A. Growing statistical evidence reveals the disproportionate impact of police violence on Black Americans ................. 22 B. Police violence against Black Americans compounds multiple forms of discrimination ............................................ 23 C. The treatment of Black Americans has been repeatedly condemned by international bodies ...................................... 25 D. Police killings are a uniquely urgent problem ............................................................................................................. 25 II. Legal Framework Regulating the Use of Force by Police ................................................................................................ -

100 Years of Barzun by Donors Kraft and Campbell

OPEN WIDE KARA WALKER SIEMENS Columbia Expands On Exhibit at SCIENCE DAY its Dental Plan | 5 The Whitney| 2 for Budding Scientists | 6 VOL. 33, NO. 04 NEWS AND IDEAS FOR THE COLUMBIA COMMUNITY OCTOBER 25, 2007 Athletic Goal: Climate Scientists Work To Battle $100 Million Disease By Bridget O’Brian By Clare Oh olumbia launched its $100 mil- lion campaign to transform the he International Research CUniversity’s athletics program, Institute for Climate and and in recognition of a $5 million Society (IRI), housed at gift, the playing field at Lawrence T Columbia’s Lamont campus A. Wien Stadium was named the in Palisades, New York, is Robert K. Kraft Field. Kraft is a 1963 graduate of Columbia College working with policy makers who now owns the New England in the nation of Colombia to Patriots. The field was renamed show how climate forecasts during homecoming weekend. can help communities better In addition to that gift, William prepare for climate-sensitive C. Campbell, chairman of the Uni- disease outbreaks. versity’s board of trustees and him- IRI scientists work around self a former captain and head coach the world to expand the knowl- of Lions football, pledged more than edge of climate and its rela- $10 million to the athletics initia- tionship to health, agriculture, tive. There were eight other gifts of water, and other sectors, $1 million or more. The Columbia Campaign for and help communities better Athletics: Achieving Excellence, adapt to changes that affect part of the University’s $4 billion their lives and livelihoods. capital campaign, has raised $46 Over the past three de- million so far. -

Cataloging Service Bulletin 102, Fall 2003

ISSN 0160-8029 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS/WASHINGTON CATALOGING SERVICE BULLETIN LIBRARY SERVICES Number 102, Fall 2003 Editor: Robert M. Hiatt CONTENTS Page DESCRIPTIVE CATALOGING Library of Congress Rule Interpretations 2 SUBJECT CATALOGING Subdivision Simplification Progress 48 Changed or Cancelled Free-Floating Subdivisions 49 Aboriginal Australians and Aboriginal Tasmanians 49 Subject Headings of Current Interest 50 Revised LC Subject Headings 50 Subject Headings Replaced by Name Headings 58 MARC Language Codes 58 ROMANIZATION Change in Yiddish Romanization Practice 58 Editorial postal address: Cataloging Policy and Support Office, Library Services, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540-4305 Editorial electronic mail address: [email protected] Editorial fax number: (202) 707-6629 Subscription address: Customer Support Team, Cataloging Distribution Service, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20541-4912 Subscription electronic mail address: [email protected] Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 78-51400 ISSN 0160-8029 Key title: Cataloging service bulletin Copyright ©2003 the Library of Congress, except within the U.S.A. DESCRIPTIVE CATALOGING LIBRARY OF CONGRESS RULE INTERPRETATIONS (LCRI) Cumulative index of LCRI to the Anglo-American Cataloguing Rules, second edition, 2002 revision, that have appeared in issues of Cataloging Service Bulletin. Any LCRI previously published but not listed below is no longer applicable and has been cancelled. Lines in the margins ( , ) of revised interpretations indicate where changes have occurred. -

The Stelliferous Fold : Toward a Virtual Law of Literature’S Self- Formation / Rodolphe Gasche´.—1St Ed

T he S telliferous Fold he Stelliferous Fold Toward a V irtual L aw of TL iterature’ s S elf-Formation R odolphe G asche´ fordham university press New York 2011 Copyright ᭧ 2011 Fordham University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. Fordham University Press has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or third-party Internet websites referred to in this publication and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate. Fordham University Press also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats. Some content that appears in print may not be available in electronic books. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gasche´, Rodolphe. The stelliferous fold : toward a virtual law of literature’s self- formation / Rodolphe Gasche´.—1st ed. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN 978-0-8232-3434-9 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8232-3435-6 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8232-3436-3 (ebk.) 1. Literature—Philosophy. 2. Literature—History and criticism—Theory, etc.I. Title. PN45.G326 2011 801—dc22 2011009669 Printed in the United States of America 131211 54321 First edition For Bronia Karst and Alexandra Gasche´ contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction 1 Part I. Scenarios for a Theory 1. Un-Staging the Beginning: Herman Melville’s Cetology 27 2. -

Prospero's Monsters: Authenticity, Identity, and Hybridity in the Post-Colonial Age

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU 18th Annual Africana Studies Student Research Africana Studies Student Research Conference Conference and Luncheon Feb 12th, 10:30 AM - 11:50 AM Prospero's Monsters: Authenticity, Identity, and Hybridity in the Post-Colonial Age Dominique Pen Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/africana_studies_conf Part of the African Languages and Societies Commons Pen, Dominique, "Prospero's Monsters: Authenticity, Identity, and Hybridity in the Post-Colonial Age" (2016). Africana Studies Student Research Conference. 3. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/africana_studies_conf/2016/002/3 This Event is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences and Events at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Africana Studies Student Research Conference by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. Pen1 Prospero’s Monsters: Authenticity, Identity, and Hybridity in the Post-Colonial Age Dominique Pen M.A. Candidate, Art History, School of Art 18th Annual Africana Studies Student Research Conference Pen2 In 2005, Yinka Shonibare was offered the prestigious distinction of becoming recognized as a Member of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (MBE). As an artist whose work is characterized by his direct engagement with and critiques of power, the establishment, colonialism and imperialism, in many cases specifically relating to Britain’s past and present, some questioned whether he was going to refuse the honor. This inquiry was perhaps encouraged -

On Gender, Sainthood, and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome

History is not the past. It is the stories we tell about the past. How we tell these stories – triumphantly or self-critically, metaphysically or dialectically – has a lot to do with whether we cut short or advance our evolution as human beings. 01/21 – Grace Lee Boggs1 Part 1: Her Second Coming The Nailing of the Cross of St. Kümmernis depicts the fourteenth-century crucifixion of St. Wilgefortis, a medieval bearded female saint. The early nineteenth-century painting by Leopold Sam Richardson Pellaucher replaced another depiction of the saint at St. Veits Chapel in Austria, which had been destroyed by an overzealous Franciscan A Saintly Curse: clerk. Rather than the typical image of Wilgefortis already nailed to the cross, On Gender, Pellaucher opted to depict the scene leading up to her crucifixion, showing a distressed St. Sainthood, and Wilgefortis, an angry father who has ordered his daughter’s execution, and weeping female witnesses to the martyrdom.2 In choosing this Polycystic moment, the painting also equates Wilgefortis’s crucifixion with the rebirth or renewal associated Ovary with generic Christian interpretations of Christ. Christ’s crucifixion is symbolic of a second coming, his resurrection; Wilgefortis’s “second Syndrome e m coming” is perhaps representative of a o r d necessary escape to a separate life in order to n y begin anew. S y r ÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊÊOriginally either a pagan noblewoman or the a v O princess of Portugal (her origins are disputed), c i t St. Wilgefortis was promised to a suitor by her n s o y 3 s c father. -

1 Introduction the Empire at the End of Decadence the Social, Scientific

1 Introduction The Empire at the End of Decadence The social, scientific and industrial revolutions of the later nineteenth century brought with them a ferment of new artistic visions. An emphasis on scientific determinism and the depiction of reality led to the aesthetic movement known as Naturalism, which allowed the human condition to be presented in detached, objective terms, often with a minimum of moral judgment. This in turn was counterbalanced by more metaphorical modes of expression such as Symbolism, Decadence, and Aestheticism, which flourished in both literature and the visual arts, and tended to exalt subjective individual experience at the expense of straightforward depictions of nature and reality. Dismay at the fast pace of social and technological innovation led many adherents of these less realistic movements to reject faith in the new beginnings proclaimed by the voices of progress, and instead focus in an almost perverse way on the imagery of degeneration, artificiality, and ruin. By the 1890s, the provocative, anti-traditionalist attitudes of those writers and artists who had come to be called Decadents, combined with their often bizarre personal habits, had inspired the name for an age that was fascinated by the contemplation of both sumptuousness and demise: the fin de siècle. These artistic and social visions of degeneration and death derived from a variety of inspirations. The pessimistic philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860), who had envisioned human existence as a miserable round of unsatisfied needs and desires that might only be alleviated by the contemplation of works of art or the annihilation of the self, contributed much to fin-de-siècle consciousness.1 Another significant influence may be found in the numerous writers and artists whose works served to link the themes and imagery of Romanticism 2 with those of Symbolism and the fin-de-siècle evocations of Decadence, such as William Blake, Edgar Allen Poe, Eugène Delacroix, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Charles Baudelaire, and Gustave Flaubert. -

WASHINGTON, B.C. March 27, 1973. Jacques Barzun, Prominent

SIXTH STREET AT CONSTITUTION AVENUE NW WASHINGTON DC 20565 • 737-4215 extension 224 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE JACQUES BARZUN TO DELIVER 1973 MELLON LECTURES IN THE FINE ARTS WASHINGTON, B.C. March 27, 1973. Jacques Barzun, prominent educator, author and cultural historian, will deliver the 22nd annual Andrew W, Mellon Lectures in the Fine Arts at the National Gallery of Art beginning Sunday April 1. The title of Professor Barzun's Mellon Lectures is The Use and Abuse of Art, with subtitles in the six-part series ranging from "Why Art Must Be Challenged" and "The Rise of Art as Religion" to "Art and Its Tempter, Science" and "Art in the Vacuum of Belief." The other titles are "Art the Destroyer" and "Art the Redeemer." The lectures will be given on six consecutive Sundays at 4:00 p.m. from April 1 through May 6 in the National Gallery Auditorium. The series is open to the public without charge. Professor Barzun 1 s publications include The French Race, Romanticism and the Modern Ego, Darwin, Marx, Wagner, and Berlioz and His Century. Among his critical works are Teacher in America, The House of Intellect, and The American University: How It Runs, Where It is Going. A native of France, Professor Barzun received his B.A 0 degree from Columbia College in New York in 1927 and began to teach there the same year. He also received his M.A. (1928) and Ph.D. (1932) from Columbia, where he became a full professor in 1945, (more) JACQUES BARZUN TO DELIVER 1973 MELLON LECTURES IN THE FINE ARTS -2 specializing in comtemporary cultural history.