(For Color Plates, See Pages 27– 46) 152 Participants 155 Institutional

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Checklist of Helminths from Lizards and Amphisbaenians (Reptilia, Squamata) of South America Ticle R A

The Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins including Tropical Diseases ISSN 1678-9199 | 2010 | volume 16 | issue 4 | pages 543-572 Checklist of helminths from lizards and amphisbaenians (Reptilia, Squamata) of South America TICLE R A Ávila RW (1), Silva RJ (1) EVIEW R (1) Department of Parasitology, Botucatu Biosciences Institute, São Paulo State University (UNESP – Univ Estadual Paulista), Botucatu, São Paulo State, Brazil. Abstract: A comprehensive and up to date summary of the literature on the helminth parasites of lizards and amphisbaenians from South America is herein presented. One-hundred eighteen lizard species from twelve countries were reported in the literature harboring a total of 155 helminth species, being none acanthocephalans, 15 cestodes, 20 trematodes and 111 nematodes. Of these, one record was from Chile and French Guiana, three from Colombia, three from Uruguay, eight from Bolivia, nine from Surinam, 13 from Paraguay, 12 from Venezuela, 27 from Ecuador, 17 from Argentina, 39 from Peru and 103 from Brazil. The present list provides host, geographical distribution (with the respective biome, when possible), site of infection and references from the parasites. A systematic parasite-host list is also provided. Key words: Cestoda, Nematoda, Trematoda, Squamata, neotropical. INTRODUCTION The present checklist summarizes the diversity of helminths from lizards and amphisbaenians Parasitological studies on helminths that of South America, providing a host-parasite list infect squamates (particularly lizards) in South with localities and biomes. America had recent increased in the past few years, with many new records of hosts and/or STUDIED REGIONS localities and description of several new species (1-3). -

Nitrogen Containing Volatile Organic Compounds

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit Nitrogen containing Volatile Organic Compounds Verfasserin Olena Bigler angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Pharmazie (Mag.pharm.) Wien, 2012 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 996 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Pharmazie Betreuer: Univ. Prof. Mag. Dr. Gerhard Buchbauer Danksagung Vor allem lieben herzlichen Dank an meinen gütigen, optimistischen, nicht-aus-der-Ruhe-zu-bringenden Betreuer Herrn Univ. Prof. Mag. Dr. Gerhard Buchbauer ohne dessen freundlichen, fundierten Hinweisen und Ratschlägen diese Arbeit wohl niemals in der vorliegenden Form zustande gekommen wäre. Nochmals Danke, Danke, Danke. Weiteres danke ich meinen Eltern, die sich alles vom Munde abgespart haben, um mir dieses Studium der Pharmazie erst zu ermöglichen, und deren unerschütterlicher Glaube an die Fähigkeiten ihrer Tochter, mich auch dann weitermachen ließ, wenn ich mal alles hinschmeissen wollte. Auch meiner Schwester Ira gebührt Dank, auch sie war mir immer eine Stütze und Hilfe, und immer war sie da, für einen guten Rat und ein offenes Ohr. Dank auch an meinen Sohn Igor, der mit viel Verständnis akzeptierte, dass in dieser Zeit meine Prioritäten an meiner Diplomarbeit waren, und mein Zeitbudget auch für ihn eingeschränkt war. Schliesslich last, but not least - Dank auch an meinen Mann Joseph, der mich auch dann ertragen hat, wenn ich eigentlich unerträglich war. 2 Abstract This review presents a general analysis of the scienthr information about nitrogen containing volatile organic compounds (N-VOC’s) in plants. -

Iii Pontificia Universidad Católica Del

III PONTIFICIA UNIVERSIDAD CATÓLICA DEL ECUADOR FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS EXACTAS Y NATURALES ESCUELA DE CIENCIAS BIOLÓGICAS Un método integrativo para evaluar el estado de conservación de las especies y su aplicación a los reptiles del Ecuador Tesis previa a la obtención del título de Magister en Biología de la Conservación CAROLINA DEL PILAR REYES PUIG Quito, 2015 IV CERTIFICACIÓN Certifico que la disertación de la Maestría en Biología de la Conservación de la candidata Carolina del Pilar Reyes Puig ha sido concluida de conformidad con las normas establecidas; por tanto, puede ser presentada para la calificación correspondiente. Dr. Omar Torres Carvajal Director de la Disertación Quito, Octubre del 2015 V AGRADECIMIENTOS A Omar Torres-Carvajal, curador de la División de Reptiles del Museo de Zoología de la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador (QCAZ), por su continua ayuda y contribución en todas las etapas de este estudio. A Andrés Merino-Viteri (QCAZ) por su valiosa ayuda en la generación de mapas de distribución potencial de reptiles del Ecuador. A Santiago Espinosa y Santiago Ron (QCAZ) por sus acertados comentarios y correcciones. A Ana Almendáriz por haber facilitado las localidades geográficas de presencia de ciertos reptiles del Ecuador de la base de datos de la Escuela Politécnica Nacional (EPN). A Mario Yánez-Muñoz de la División de Herpetología del Museo Ecuatoriano de Ciencias Naturales del Instituto Nacional de Biodiversidad (DHMECN-INB), por su ayuda y comentarios a la evaluación de ciertos reptiles del Ecuador. A Marcio Martins, Uri Roll, Fred Kraus, Shai Meiri, Peter Uetz y Omar Torres- Carvajal del Global Assessment of Reptile Distributions (GARD) por su colaboración y comentarios en las encuestas realizadas a expertos. -

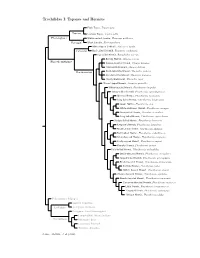

Topazes and Hermits

Trochilidae I: Topazes and Hermits Fiery Topaz, Topaza pyra Topazini Crimson Topaz, Topaza pella Florisuginae White-necked Jacobin, Florisuga mellivora Florisugini Black Jacobin, Florisuga fusca White-tipped Sicklebill, Eutoxeres aquila Eutoxerini Buff-tailed Sicklebill, Eutoxeres condamini Saw-billed Hermit, Ramphodon naevius Bronzy Hermit, Glaucis aeneus Phaethornithinae Rufous-breasted Hermit, Glaucis hirsutus ?Hook-billed Hermit, Glaucis dohrnii Threnetes ruckeri Phaethornithini Band-tailed Barbthroat, Pale-tailed Barbthroat, Threnetes leucurus ?Sooty Barbthroat, Threnetes niger ?Broad-tipped Hermit, Anopetia gounellei White-bearded Hermit, Phaethornis hispidus Tawny-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis syrmatophorus Mexican Hermit, Phaethornis mexicanus Long-billed Hermit, Phaethornis longirostris Green Hermit, Phaethornis guy White-whiskered Hermit, Phaethornis yaruqui Great-billed Hermit, Phaethornis malaris Long-tailed Hermit, Phaethornis superciliosus Straight-billed Hermit, Phaethornis bourcieri Koepcke’s Hermit, Phaethornis koepckeae Needle-billed Hermit, Phaethornis philippii Buff-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis subochraceus Scale-throated Hermit, Phaethornis eurynome Sooty-capped Hermit, Phaethornis augusti Planalto Hermit, Phaethornis pretrei Pale-bellied Hermit, Phaethornis anthophilus Stripe-throated Hermit, Phaethornis striigularis Gray-chinned Hermit, Phaethornis griseogularis Black-throated Hermit, Phaethornis atrimentalis Reddish Hermit, Phaethornis ruber ?White-browed Hermit, Phaethornis stuarti ?Dusky-throated Hermit, Phaethornis squalidus Streak-throated Hermit, Phaethornis rupurumii Cinnamon-throated Hermit, Phaethornis nattereri Little Hermit, Phaethornis longuemareus ?Tapajos Hermit, Phaethornis aethopygus ?Minute Hermit, Phaethornis idaliae Polytminae: Mangos Lesbiini: Coquettes Lesbiinae Coeligenini: Brilliants Patagonini: Giant Hummingbird Lampornithini: Mountain-Gems Tro chilinae Mellisugini: Bees Cynanthini: Emeralds Trochilini: Amazilias Source: McGuire et al. (2014).. -

Myrciaria Floribunda, Le Merisier-Cerise, Source Dela Guavaberry, Liqueur Traditionnelle De L’Ile De Saint-Martin Charlélie Couput

Myrciaria floribunda, le Merisier-Cerise, source dela Guavaberry, liqueur traditionnelle de l’ile de Saint-Martin Charlélie Couput To cite this version: Charlélie Couput. Myrciaria floribunda, le Merisier-Cerise, source de la Guavaberry, liqueur tradi- tionnelle de l’ile de Saint-Martin. Sciences du Vivant [q-bio]. 2019. dumas-02297127 HAL Id: dumas-02297127 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-02297127 Submitted on 25 Sep 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. UNIVERSITE DE BORDEAUX U.F.R. des Sciences Pharmaceutiques Année 2019 Thèse n°45 THESE pour le DIPLOME D'ETAT DE DOCTEUR EN PHARMACIE Présentée et soutenue publiquement le : 6 juin 2019 par Charlélie COUPUT né le 18/11/1988 à Pau (Pyrénées-Atlantiques) MYRCIARIA FLORIBUNDA, LE MERISIER-CERISE, SOURCE DE LA GUAVABERRY, LIQUEUR TRADITIONNELLE DE L’ILE DE SAINT-MARTIN MEMBRES DU JURY : M. Pierre WAFFO-TÉGUO, Professeur ........................ ....Président M. Alain BADOC, Maitre de conférences ..................... ....Directeur de thèse M. Jean MAPA, Docteur en pharmacie ......................... ....Assesseur ! !1 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !2 REMERCIEMENTS À monsieur Alain Badoc, pour m’avoir épaulé et conseillé tout au long de mon travail. Merci pour votre patience et pour tous vos précieux conseils qui m’ont permis d’achever cette thèse. -

Chemical Composition and Antioxidant Activity of Genipa Americana L

Journal of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences December 2014, Vol. 3, No. 4, pp. 51-61 ISSN: 2334-2404 (Print), 2334-2412 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). 2014. All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/jaes.v3n4a4 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.15640/jaes.v3n4a4 Chemical Composition and Antioxidant Activity of Genipa Americana L. (Jenipapo) of the Brazilian Cerrado Rayssa Gabriela Costa Lima Porto1, Bárbara Verônica Sousa Cardoso1, Nara Vanessa dos Anjos Barros1, Edjane Mayara Ferreira Cunha1, Marcos Antônio da Mota Araújo2, & Regilda Saraiva dos Reis Moreira-Araújo3 Abstract Brazil has the largest biodiversity of any country in the world, which includes a large number of fruit species. Cerrado, a Brazilian biome that has a large number of underexploited native and exotic fruit species, is of potential interest to the agroindustry and a possible future source of income for the local population. This paper presents the centesimal composition, phenolic contents, anthocyanin, flavonoids, and antioxidant activity of Genipa americana L. fruit. The results indicated the following composition: moisture (75.00%), lipids (1.60%), proteins (0.67%), carbohydrates (20.50%), and ash (2.20%). The Genipa americana fruit contained considerable amounts of phenolic compounds (857.10 mgGAE.100-1 g) and flavonoids (728.00 mg.100-1 g), which contribute to its high antioxidant activity. This study highlights the potential of this fruit as an important source of both nutritional and bioactive compounds available in the native Brazilian flora. Keywords: Genipa americana L. (jenipapo), food chemistry, phenolic compounds, antioxidant capacity 1. Introduction Brazil has the largest biodiversity of any country in the world, which includes a large number of fruit species (Leterme et al., 2006 ). -

Ethnopharmacology of Fruit Plants

molecules Review Ethnopharmacology of Fruit Plants: A Literature Review on the Toxicological, Phytochemical, Cultural Aspects, and a Mechanistic Approach to the Pharmacological Effects of Four Widely Used Species Aline T. de Carvalho 1, Marina M. Paes 1 , Mila S. Cunha 1, Gustavo C. Brandão 2, Ana M. Mapeli 3 , Vanessa C. Rescia 1 , Silvia A. Oesterreich 4 and Gustavo R. Villas-Boas 1,* 1 Research Group on Development of Pharmaceutical Products (P&DProFar), Center for Biological and Health Sciences, Federal University of Western Bahia, Rua Bertioga, 892, Morada Nobre II, Barreiras-BA CEP 47810-059, Brazil; [email protected] (A.T.d.C.); [email protected] (M.M.P.); [email protected] (M.S.C.); [email protected] (V.C.R.) 2 Physical Education Course, Center for Health Studies and Research (NEPSAU), Univel University Center, Cascavel-PR, Av. Tito Muffato, 2317, Santa Cruz, Cascavel-PR CEP 85806-080, Brazil; [email protected] 3 Research Group on Biomolecules and Catalyze, Center for Biological and Health Sciences, Federal University of Western Bahia, Rua Bertioga, 892, Morada Nobre II, Barreiras-BA CEP 47810-059, Brazil; [email protected] 4 Faculty of Health Sciences, Federal University of Grande Dourados, Dourados, Rodovia Dourados, Itahum Km 12, Cidade Universitaria, Caixa. postal 364, Dourados-MS CEP 79804-970, Brazil; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +55-(77)-3614-3152 Academic Editors: Raffaele Pezzani and Sara Vitalini Received: 22 July 2020; Accepted: 31 July 2020; Published: 26 August 2020 Abstract: Fruit plants have been widely used by the population as a source of food, income and in the treatment of various diseases due to their nutritional and pharmacological properties. -

Colombia Mega II 1St – 30Th November 2016 (30 Days) Trip Report

Colombia Mega II 1st – 30th November 2016 (30 Days) Trip Report Black Manakin by Trevor Ellery Trip Report compiled by tour leader: Trevor Ellery Trip Report – RBL Colombia - Mega II 2016 2 ___________________________________________________________________________________ Top ten birds of the trip as voted for by the Participants: 1. Ocellated Tapaculo 6. Blue-and-yellow Macaw 2. Rainbow-bearded Thornbill 7. Red-ruffed Fruitcrow 3. Multicolored Tanager 8. Sungrebe 4. Fiery Topaz 9. Buffy Helmetcrest 5. Sword-billed Hummingbird 10. White-capped Dipper Tour Summary This was one again a fantastic trip across the length and breadth of the world’s birdiest nation. Highlights were many and included everything from the flashy Fiery Topazes and Guianan Cock-of- the-Rocks of the Mitu lowlands to the spectacular Rainbow-bearded Thornbills and Buffy Helmetcrests of the windswept highlands. In between, we visited just about every type of habitat that it is possible to bird in Colombia and shared many special moments: the diminutive Lanceolated Monklet that perched above us as we sheltered from the rain at the Piha Reserve, the showy Ochre-breasted Antpitta we stumbled across at an antswarm at Las Tangaras Reserve, the Ocellated Tapaculo (voted bird of the trip) that paraded in front of us at Rio Blanco, and the male Vermilion Cardinal, in all his crimson glory, that we enjoyed in the Guajira desert on the final morning of the trip. If you like seeing lots of birds, lots of specialities, lots of endemics and enjoy birding in some of the most stunning scenery on earth, then this trip is pretty unbeatable. -

Ornithological Surveys in Serranía De Los Churumbelos, Southern Colombia

Ornithological surveys in Serranía de los Churumbelos, southern Colombia Paul G. W . Salaman, Thomas M. Donegan and Andrés M. Cuervo Cotinga 12 (1999): 29– 39 En el marco de dos expediciones biológicos y Anglo-Colombian conservation expeditions — ‘Co conservacionistas anglo-colombianas multi-taxa, s lombia ‘98’ and the ‘Colombian EBA Project’. Seven llevaron a cabo relevamientos de aves en lo Serranía study sites were investigated using non-systematic de los Churumbelos, Cauca, en julio-agosto 1988, y observations and standardised mist-netting tech julio 1999. Se estudiaron siete sitios enter en 350 y niques by the three authors, with Dan Davison and 2500 m, con 421 especes registrados. Presentamos Liliana Dávalos in 1998. Each study site was situ un resumen de los especes raros para cada sitio, ated along an altitudinal transect at c. 300- incluyendo los nuevos registros de distribución más m elevational steps, from 350–2500 m on the Ama significativos. Los resultados estabilicen firme lo zonian slope of the Serranía. Our principal aim was prioridad conservacionista de lo Serranía de los to allow comparisons to be made between sites and Churumbelos, y aluco nos encontramos trabajando with other biological groups (mammals, herptiles, junto a los autoridades ambientales locales con insects and plants), and, incorporating geographi cuiras a lo protección del marcizo. cal and anthropological information, to produce a conservation assessment of the region (full results M e th o d s in Salaman et al.4). A sizeable part of eastern During 14 July–17 August 1998 and 3–22 July 1999, Cauca — the Bota Caucana — including the 80-km- ornithological surveys were undertaken in Serranía long Serranía de los Churumbelos had never been de los Churumbelos, Department of Cauca, by two subject to faunal surveys. -

Brazil: Remote Southern Amazonia Campos Amazônicos Np & Acre

BRAZIL: REMOTE SOUTHERN AMAZONIA CAMPOS AMAZÔNICOS NP & ACRE 7 – 19 July 2015 White-breasted Antbird (Rhegmatorhina hoffmannsi), Tabajara, Rondônia © Bradley Davis trip report by Bradley Davis ([email protected] / www.birdingmatogrosso.com) photographs by Bradley Davis and Bruno Rennó Introduction: This trip had been in the making since the autumn of 2013. Duncan, an avowed antbird fanatic, contacted me after having come to the conclusion that he could no longer ignore the Rio Roosevelt given the recent batch of antbird splits and new taxa coming from the Madeira – Tapajós interfluvium. We had touched on the subject during his previous trips in Brazil, having also toyed with the idea of including an expedition-style extension to search for Brazil's biggest mega when it comes to antbirds – the Rondônia Bushbird. After some back and forth in the first two months of the following year, an e-mail came through from Duncan which ended thusly: “statement of the bleedin’ obvious: I would SERIOUSLY like to see the Bushbird.” At which point the game was on, so to speak. We began to organize an itinerary for the Rio Roosevelt with a dedicated expedition for Rondonia Bushbird. By mid-year things were coming together for a September trip, but in August we were de-railed by a minor health problem and two participants being forced to back out at the last minute. With a bushbird in the balance, we weren't about to call the whole thing off, and thus a new itinerary sans Roosevelt was hatched for 2015, an itinerary which called for about a week in the Tabajara area on the southern border of the Campos Amazônicos National Park, followed by a few days on the west bank of the rio Madeira to go for a couple of Duncan's targets in that area. -

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS) – 2009-2012 Version Available for Download From

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands (RIS) – 2009-2012 version Available for download from http://www.ramsar.org/ris/key_ris_index.htm. Categories approved by Recommendation 4.7 (1990), as amended by Resolution VIII.13 of the 8th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2002) and Resolutions IX.1 Annex B, IX.6, IX.21 and IX. 22 of the 9th Conference of the Contracting Parties (2005). Notes for compilers: 1. The RIS should be completed in accordance with the attached Explanatory Notes and Guidelines for completing the Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands. Compilers are strongly advised to read this guidance before filling in the RIS. 2. Further information and guidance in support of Ramsar site designations are provided in the Strategic Framework and guidelines for the future development of the List of Wetlands of International Importance (Ramsar Wise Use Handbook 14, 3rd edition). A 4th edition of the Handbook is in preparation and will be available in 2009. 3. Once completed, the RIS (and accompanying map(s)) should be submitted to the Ramsar Secretariat. Compilers should provide an electronic (MS Word) copy of the RIS and, where possible, digital copies of all maps. 1. Name and address of the compiler of this form: FOR OFFICE USE ONLY. DD MM YY Beatriz de Aquino Ribeiro - Bióloga - Analista Ambiental / [email protected], (95) Designation date Site Reference Number 99136-0940. Antonio Lisboa - Geógrafo - MSc. Biogeografia - Analista Ambiental / [email protected], (95) 99137-1192. Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade - ICMBio Rua Alfredo Cruz, 283, Centro, Boa Vista -RR. CEP: 69.301-140 2. -

Colombia: from the Choco to Amazonia

This gorgeous Cinnamon Screech Owl narrowly missed being our bird-of-the-trip! (Pete Morris) COLOMBIA: FROM THE CHOCO TO AMAZONIA 9/12/15 JANUARY – 5/11 FEBRUARY 2016 LEADER: PETE MORRIS Well, this was the first time that we had run our revised Colombia With a Difference tour – now aptly-named Colombia: From the Choco to Amazonia. Complete with all the trimmings, which included pre-tour visits to San Andres and Providencia, the Sooty-capped Puffbird Extension, and the post tour Mitu Extension, we managed to amass in excess of 850 species. Travelling to the Caribbean, the Pacific Coast, the High Andes and the Amazon all in one trip really was quite an experience, and the variety and diversity of species recorded, at times, almost overwhelming! Picking out just a few highlights from such a long list is difficult, but here’s just an 1 BirdQuest Tour Report:Colombia: From the Choco to Amazonia www.birdquest-tours.com The exquisite Golden-bellied Starfrontlet, one of a number of stunning hummers and our bird-of-the-trip! (Pete Morris) appetizer! The islands of San Andres and Providencia both easily gave up their endemic vireos – two Birdquest Lifers! The Sooty-capped Puffbirds were all we hoped for and a male Sapphire-bellied Hummingbird a bonus! A sneaky trip to Sumapaz National Park yielded several Green-bearded Helmetcrests and Bronze-tailed Thorn- bill. On the main tour we saw a huge number of goodies. Blue-throated, Dusky and Golden-bellied Starfrontlets (all stunners!); the rare Humboldt’s Sapphire was a Birdquest lifer; nightbirds included Black-and-white Owl and White-throated, Cinnamon and Choco Screech Owls; and a random selection of other favourites included Gorgeted Wood Quail, the much appreciated Brown Wood Rail, Beautiful Woodpecker, Chestnut-bellied Hum- mingbird, Black Inca, the brilliant Rusty-faced Parrot, Citron-throated Toucan, Recurve-billed Bushbird, Urrao Antpitta, Niceforo’s and Antioquia Wrens, the amazing Baudo Oropendola, Crested and Sooty Ant Tanagers and the rare Mountain Grackle.