Unit 1 Historiography of the Pre-Colonial Economy – Ancient

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iudaea Capta Vs. Mother Zion: the Flavian Discourse on Judaeans and Its Delegitimation in 4 Ezra

Journal for the Study of Judaism 49 (2018) 498-550 Journal for the Study of Judaism brill.com/jsj Iudaea Capta vs. Mother Zion: The Flavian Discourse on Judaeans and Its Delegitimation in 4 Ezra G. Anthony Keddie1 Assistant Professor, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada [email protected] Abstract This study proposes that the empire-wide Iudaea capta discourse should be viewed as a motivating pressure on the author of 4 Ezra. The discourse focused on Iudaea capta, Judaea captured, was pervasive across the Roman empire following the First Revolt. Though initiated by the Flavians, it became misrecognized across the Mediterranean and was expressed in a range of media. In this article, I examine the diverse evidence for this discourse and demonstrate that it not only cast Judaeans as barbaric enemies of Rome using a common set of symbols, but also attributed responsibility for a minor provincial revolt to a transregional ethnos/gens. One of the most distinctive symbols of this discourse was a personification of Judaea as a mourning woman. I argue that 4 Ezra delegitimates this Iudaea capta discourse, with its mourning woman, through the counter-image of a Mother Zion figure who transforms into the eschatological city. Keywords Iudaea capta/Judaea capta − Flavian dynasty − 4 Ezra − Roman iconography − Jewish-Roman relations − Mother Zion − apocalyptic discourse − First Jewish Revolt 1 I would like to thank Steven Friesen and L. Michael White for their helpful feedback and insightful suggestions on earlier versions of this study. © koninklijke brill nv, leiden, 2018 | doi:10.1163/15700631-12494235Downloaded from Brill.com10/06/2021 11:31:49PM via free access Iudaea Capta vs. -

VU Research Portal

VU Research Portal The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon Pirngruber, R. 2012 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Pirngruber, R. (2012). The impact of empire on market prices in Babylon: in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 - 140 B.C. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. R. Pirngruber VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT THE IMPACT OF EMPIRE ON MARKET PRICES IN BABYLON in the Late Achaemenid and Seleucid periods, ca. 400 – 140 B.C. ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad Doctor aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. -

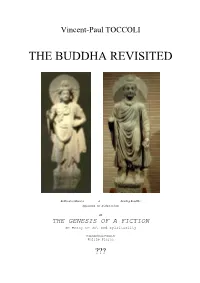

The Buddha Revisited

Vincent-Paul TOCCOLI THE BUDDHA REVISITED Bodhisattva Maitreya & Standing Bouddha Afghanistan, 1er & 2ème sicècles or THE GENESIS OF A FICTION an essay on art and spirituality Translated from French by Philip Pierce ??? "Stories do not belong to eternity "They belong to time "And out of time they grow... "It is in time "That stories, relived and redreamed "Become timeless... "Nations and people are largely the stories they feed themselves "If they tell themselves stories that are lies, "They will suffer the future consequences of those lies. "If they tell themselves stories that free their own truths "They will free their histories forfuture flowerings. (Ben OKRI, Birds of heaven, 25, 15) "Dans leur prétention à la sagesse, "Ils sont devenus fous, "Et ils ont changé la gloire du dieu incorruptible "Contre une représentation, "Simple image d`homme corruptible. (St Paul, to the Romans, 1, 22-23) C O N T E N T S INTRODUCTION FIRST PART: THE MAKING-SENSE TRANSGRESSIONS 1st SECTION: ON THE GANGES SIDE, 5th-1st cent. BC. Chap.1: The Buddhism of the Buddha Chap.2: The state of Buddhism under the last Mauryas 2nd SECTION: ON THE INDUS SIDE, 4th-1st cent. BC. Chap.3: The permanence of Philhellenism, from the Graeco-bactrians to the Scytho-Parthans Chap.4: An approach to the graeco-hellenistic influence SECOND PART: THE ARTIFICIAL FECUNDATIONS 3rd SECTION: THE SYMBOLIC IMAGINARY AND THE REPRESENTATION OF THE SACRED Chap.5: The figurative vision of Buddhism Chap.6: The aesthetic tradition of Greek sculpture 4th SECTION: THE PRECIPITATE IN SPACE -

2007 Conference Papers

Volume19 Journalof the NumismaticAs soc ratron of Austraha 2007Conference Papers Images in the Roman world Hugh Preston The role of the visual in establishing, themselves as Roman. The use of imagery reinforcing and transforming Roman seems to have created a significant degree culture is sometimes overlooked in of cohesion, and that surely was one of the traditional historical accounts. It is perhaps reasons that the Empire lasted for centuries. no surprise that the visual receives more Images reinforced cultural and attention in art history. Thus, art historian political identity. The same or similar Jas Elsner, in Imperial Rome and Christian images were used across the Empire and Triumph, wrote ‘In several significant were reused over hundreds of years, ways the Roman world was a visual although the use of imagery became more culture’ and ‘With the vast majority of the sophisticated with time as its propaganda empire’s inhabitants illiterate and often value was increasingly appreciated. unable to speak the dominant languages of The vast visual heritage left by the the elite, which were Greek in the East and Romans is an important source of infor- Latin in the West, the most direct way of mation to complement the written word, communicating was through images.’1,2 and to illuminate the vision we have of their The Roman state was immense and world. While it is important to recognize lasted for centuries. It comprised a host of visual and pictorial imagery as legitimate different ethnic groups and geophysical sources of historical information, care environments. Figure 1 shows the Empire should be taken not to rely exclusively on at its greatest extent. -

Archaeology and History of Lydia from the Early Lydian Period to Late Antiquity (8Th Century B.C.-6Th Century A.D.)

Dokuz Eylül University – DEU The Research Center for the Archaeology of Western Anatolia – EKVAM Colloquia Anatolica et Aegaea Congressus internationales Smyrnenses IX Archaeology and history of Lydia from the early Lydian period to late antiquity (8th century B.C.-6th century A.D.). An international symposium May 17-18, 2017 / Izmir, Turkey ABSTRACTS Edited by Ergün Laflı Gülseren Kan Şahin Last Update: 21/04/2017. Izmir, May 2017 Websites: https://independent.academia.edu/TheLydiaSymposium https://www.researchgate.net/profile/The_Lydia_Symposium 1 This symposium has been dedicated to Roberto Gusmani (1935-2009) and Peter Herrmann (1927-2002) due to their pioneering works on the archaeology and history of ancient Lydia. Fig. 1: Map of Lydia and neighbouring areas in western Asia Minor (S. Patacı, 2017). 2 Table of contents Ergün Laflı, An introduction to Lydian studies: Editorial remarks to the abstract booklet of the Lydia Symposium....................................................................................................................................................8-9. Nihal Akıllı, Protohistorical excavations at Hastane Höyük in Akhisar………………………………10. Sedat Akkurnaz, New examples of Archaic architectural terracottas from Lydia………………………..11. Gülseren Alkış Yazıcı, Some remarks on the ancient religions of Lydia……………………………….12. Elif Alten, Revolt of Achaeus against Antiochus III the Great and the siege of Sardis, based on classical textual, epigraphic and numismatic evidence………………………………………………………………....13. Gaetano Arena, Heleis: A chief doctor in Roman Lydia…….……………………………………....14. Ilias N. Arnaoutoglou, Κοινὸν, συμβίωσις: Associations in Hellenistic and Roman Lydia……….……..15. Eirini Artemi, The role of Ephesus in the late antiquity from the period of Diocletian to A.D. 449, the “Robber Synod”.……………………………………………………………………….………...16. Natalia S. Astashova, Anatolian pottery from Panticapaeum…………………………………….17-18. Ayşegül Aykurt, Minoan presence in western Anatolia……………………………………………...19. -

Fall 2019 Catalog, Please Contact

FALL / WINTER 2019 J with Hopkins SalesUNIVERSITY Partners PRESS I have been involved in the Association of University Presses since my fi rst job as a marketing assistant in scholarly publishing in the early 1980s. Therefore, it has been easy for me to take for granted the willingness of my university press colleagues to share information at the AUPresses Annual Meeting and, once the internet was invented, to continue conversations online all year long. And so, many of you will not be surprised by how excited we are to introduce a collaborative new entity called Hopkins Sales Partners. By pooling our resources and building scale, we know that university presses can be more successful in meeting our missions to disseminate knowledge far and wide and be fi nancially responsible in the process. Building new sales opportunities together with our sister presses seemed only natural to us here at JHUP. Barbara Kline Pope circa 1990. We welcome Wesleyan University Press, Northeastern University Press, Family Development Press, University of New Orleans Press, and Central European University Press to Hopkins Sales Partners and invite you to discover their exceptional books on pages 90–107. I hope that as you explore the books from our partner presses and from our own Johns Hopkins University Press you will fi nd our collective o erings remarkable and inspiring. [email protected] Table of Contents General Interest 2 History Health & Wellness 28 American History 24–25, 43–46, 86–87, 89 Scholarly and Professional 34 Ancient History 51–53 The Complete -

In the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit

Case: 17-17531, 04/02/2018, ID: 10821327, DktEntry: 13-1, Page 1 of 111 IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT WINDING CREEK SOLAR LLC, Case No. 17-17531 Plaintiff-Appellant, On Appeal from the United States v. District Court for the Northern District of California CARLA PETERMAN; MARTHA No. 3:13-cv-04934-JD GUZMAN ACEVES; LIANE Hon. James Donato RANDOLPH; CLIFFORD RECHTSCHAFFEN; MICHAEL PICKER, in their official capacities as Commissioners of the California Public Utilities Commission, Defendants-Appellees. Case No. 17-17532 WINDING CREEK SOLAR LLC, On Appeal from the United States Plaintiff-Appellee, District Court for the Northern District v. of California No. 3:13-cv-04934-JD CARLA PETERMAN; MARTHA Hon. James Donato GUZMAN ACEVES; LIANE RANDOLPH; CLIFFORD RECHTSCHAFFEN; MICHAEL PICKER, in their official capacities as Commissioners of the California Public Utilities Commission, Defendants-Appellants. APPELLANT’S FIRST BRIEF ON CROSS-APPEAL Thomas Melone ALLCO RENEWABLE ENERGY LTD. 1740 Broadway, 15th Floor New York, NY 10019 Telephone: (212) 681-1120 Email: [email protected] Attorneys for Appellant WINDING CREEK SOLAR LLC Case: 17-17531, 04/02/2018, ID: 10821327, DktEntry: 13-1, Page 2 of 111 CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT Winding Creek Solar LLC is 100% owned by Allco Finance Limited, which is a privately held company in the business of developing solar energy projects. Allco Finance Limited has no parent companies, and no publicly held company owns 10 percent or more of its stock. /s/ Thomas Melone i Case: 17-17531, 04/02/2018, ID: 10821327, DktEntry: 13-1, Page 3 of 111 TABLE OF CONTENTS CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT ................................................... -

Calendar of Roman Events

Introduction Steve Worboys and I began this calendar in 1980 or 1981 when we discovered that the exact dates of many events survive from Roman antiquity, the most famous being the ides of March murder of Caesar. Flipping through a few books on Roman history revealed a handful of dates, and we believed that to fill every day of the year would certainly be impossible. From 1981 until 1989 I kept the calendar, adding dates as I ran across them. In 1989 I typed the list into the computer and we began again to plunder books and journals for dates, this time recording sources. Since then I have worked and reworked the Calendar, revising old entries and adding many, many more. The Roman Calendar The calendar was reformed twice, once by Caesar in 46 BC and later by Augustus in 8 BC. Each of these reforms is described in A. K. Michels’ book The Calendar of the Roman Republic. In an ordinary pre-Julian year, the number of days in each month was as follows: 29 January 31 May 29 September 28 February 29 June 31 October 31 March 31 Quintilis (July) 29 November 29 April 29 Sextilis (August) 29 December. The Romans did not number the days of the months consecutively. They reckoned backwards from three fixed points: The kalends, the nones, and the ides. The kalends is the first day of the month. For months with 31 days the nones fall on the 7th and the ides the 15th. For other months the nones fall on the 5th and the ides on the 13th. -

Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean Culture

ANTONIJE SHKOKLJEV SLAVE NIKOLOVSKI - KATIN PREHISTORY CENTRAL BALKANS CRADLE OF AEGEAN CULTURE Prehistory - Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean culture By Antonije Shkokljev Slave Nikolovski – Katin Translated from Macedonian to English and edited By Risto Stefov Prehistory - Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean culture Published by: Risto Stefov Publications [email protected] Toronto, Canada All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without written consent from the author, except for the inclusion of brief and documented quotations in a review. Copyright 2013 by Antonije Shkokljev, Slave Nikolovski – Katin & Risto Stefov e-book edition 2 Index Index........................................................................................................3 COMMON HISTORY AND FUTURE ..................................................5 I - GEOGRAPHICAL CONFIGURATION OF THE BALKANS.........8 II - ARCHAEOLOGICAL DISCOVERIES .........................................10 III - EPISTEMOLOGY OF THE PANNONIAN ONOMASTICS.......11 IV - DEVELOPMENT OF PALEOGRAPHY IN THE BALKANS....33 V – THRACE ........................................................................................37 VI – PREHISTORIC MACEDONIA....................................................41 VII - THESSALY - PREHISTORIC AEOLIA.....................................62 VIII – EPIRUS – PELASGIAN TESPROTIA......................................69 -

Centurions, Quarries, and the Emperor

Comp. by: C. Vijayakumar Stage : Revises1 ChapterID: 0002507155 Date:5/5/15 Time:11:37:24 Filepath://ppdys1122/BgPr/OUP_CAP/IN/Process/0002507155.3d View metadata,Dictionary : OUP_UKdictionarycitation and similar 289 papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – REVISES, 5/5/2015,provided SPi by University of Liverpool Repository 16 Centurions, Quarries, and the Emperor Alfred M. Hirt INTRODUCTION The impact of Rome on the exploitation of natural resources remains highly visible in the many ancient stone and marble quarries dotting the landscape of the former empire. Not only do they reveal the techniques employed in separating the marble or granite from the rock face, the distribution of their output can still be traced. The progressively more scientific determination of type and origin of these stones used in sacred and profane architecture of the Roman Empire reveals an increasingly detailed image of the distributive patterns of coloured stones. Even so, the analysis of these patterns stays vexed: the written sources are frightfully mute on the core issues, expressly on the emperor’s role in the quarrying industry and his impact on the marble trade. Scholarly discourse has oscillated between two positions: John Ward- Perkins argued that by the mid-first century AD all ‘principal’ quarries were ‘nationalized’, i.e. put under imperial control and leased out to contractors for rent; the quarries were a source of revenue for the emperor, the distribution of its output driven by commercial factors.1 Clayton Fant, however, offered a different view: the emperor monopolized the use of coloured and white marbles and their sources not for profit, but for ‘prestige’, consolidating his position as unchallenged patron and benefactor of the empire. -

AAS - Planning Your Course of Study 2019-2020

AAS - Planning Your Course of Study 2019-2020 Required Courses for an AAS degree PREREQUISITE COURSES AD 101 – Alcohol Use and Addiction (3 CR) WR 121 – English Composition (4 CR) LIB 101 – Library Research and Beyond (1 CR) AD 153 – Theories of Counseling (3 CR) AD 160 – Basic Counseling (4 CR) PRIORITY CLASSES – Recommended to be taken prior to cohort to increase your chance of admission (2 PTS for Admission) AD 102 – Drug Use and Addiction (practicum prerequisite) AD 106 – Smoking Cessation (1CR) AD 156 – Ethical and Professional Issues (3 CR) PSY 239 – Abnormal Psychology (requires either PSY 201A or AD 102 prior) RECOMMENDED – CAS 100A or CAS 133 (to strengthen your technology skills) See advisor for more info. COHORT CLASSES AD 152 – Group Counseling and Addiction (3 CR) (This class should be taken during the first term of practicum) AD 154 – Client Record Management and Addiction (3 CR) AD 161 – Motivational Interviewing (4 CR) AD 278 – Practicum Preparation (1 CR) ADDITIONAL REQUIRED COURSES FOR ASSOCIATES DEGREE – THESE CAN BE TAKEN CONCURRENTLY WITH YOUR PRACTICUM (200 LEVEL CLASSES RECOMMENDED TO TAKE WITH PRACTICUM) AD 103 – Women and Addiction (3 CR) AD 104 – Multicultural Counseling (3 CR) AD 184 – Men and Addiction (3 CR) AD 202 – Trauma and Recovery (3 CR) AD 255 – Multiple Diagnoses (PREREQ/CONCURRENT AD 101, AD 102, WRN 121 PSY 239) One (1) Arts and Letters General Education Requirement (4 CR class) One (1) Science/Mathematics/Computer Studies General Education Req. (4 CR class) Math coursework -

Dio Chrysostom (707) Dowden, Ken

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Portal Dio Chrysostom (707) Dowden, Ken License: None: All rights reserved Document Version Peer reviewed version Citation for published version (Harvard): Dowden, K 2015, Dio Chrysostom (707). in I Worthington (ed.), Brills New Jacoby. Brill's New Jacoby, Brill. Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: Published in Brill's New Jacoby. Final version of record available online: http://referenceworks.brillonline.com/browse/brill-s-new-jacoby General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. When citing, please reference the published version. Take down policy While the University of Birmingham exercises care and attention in making items available there are rare occasions when an item has been uploaded in error or has been deemed to be commercially or otherwise sensitive.