Minimum Headspace and Maximum COL So a Chamber Reamer, A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bamboo Nail: a Novel Connector for Timber Assemblies

Tech Science Press DOI: 10.32604/jrm.2021.015193 ARTICLE Bamboo Nail: A Novel Connector for Timber Assemblies Yehan Xu, Zhifu Dong, Chong Jia, Zhiqiang Wang* and Xiaoning Lu* College of Materials Science and Engineering, Nanjing Forestry University, Nanjing, 210037, China *Corresponding Authors: Zhiqiang Wang. Email: [email protected]; Xiaoning Lu. Email: [email protected] Received: 30 November 2020 Accepted: 18 January 2021 ABSTRACT Nail connection is widely used in engineering and construction fields. In this study, bamboo nail was proposed as a novel connector for timber assemblies. Penetration depth of bamboo nail into wood was predicted and tested. The influence of nail parameters (length, radius and ogive radius) on penetration depth were verified. For both tested and predicted results, the penetration depth of bamboo nail increased with the increasing length, radius or ogive radius. In addition, the effect of densification on penetration depth or mechanical properties was evaluated. 1.12 g/cm3 was a critical density when densification was needed, and further increment of density would decrease the penetration depth of nail. The results of this study manifests that the proposed model is capable to predict the penetration depth of bamboo nail. These findings may provide new insight into efficiently utilization of bamboo resources. KEYWORDS Nail connection; bamboo nail; penetration depth; nail parameter; densification 1 Introduction Facing on energetic and environmental challenges, sustainable materials for structural application have being worldwide used, such as wood and bamboo [1]. The applications of wood and bamboo have significant effect on the global environment, as wood and bamboo can absorb carbon dioxide from the atmosphere as they grow [2−4]. -

On the Temporal Dynamics of Spatial Stimulus-Response Transfer Between Spatial Incompatibility and Simon Tasks

ORIGINAL RESEARCH ARTICLE published: 19 August 2014 doi: 10.3389/fnins.2014.00243 On the temporal dynamics of spatial stimulus-response transfer between spatial incompatibility and Simon tasks Jason Ivanoff 1*, Ryan Blagdon 1, Stefanie Feener 1, Melanie McNeil 1 and Paul H. Muir 2 1 Department of Psychology, Saint Mary’s University, Halifax, NS, Canada 2 Department of Mathematics and Computing Science, Saint Mary’s University, Halifax, NS, Canada Edited by: The Simon effect refers to the performance (response time and accuracy) advantage Dominic Standage, Queen’s for responses that spatially correspond to the task-irrelevant location of a stimulus. It University, Canada has been attributed to a natural tendency to respond toward the source of stimulation. Reviewed by: When location is task-relevant, however, and responses are intentionally directed away Leendert Van Maanen, University of Amsterdam, Netherlands (incompatible) or toward (compatible) the source of the stimulation, there is also an Tiffany Cheing Ho, University of advantage for spatially compatible responses over spatially incompatible responses. California, San Francisco, USA Interestingly, a number of studies have demonstrated a reversed, or reduced, Simon effect *Correspondence: following practice with a spatial incompatibility task. One interpretation of this finding Jason Ivanoff, Department of is that practicing a spatial incompatibility task disables the natural tendency to respond Psychology, Saint Mary’s University, Halifax, NS, B3H 3C3, Canada toward stimuli. Here, the temporal dynamics of this stimulus-response (S-R) transfer e-mail: [email protected] were explored with speed-accuracy trade-offs (SATs). All experiments used the mixed-task paradigm in which Simon and spatial compatibility/incompatibility tasks were interleaved across blocks of trials. -

Precision Measurement Station

INSTRUCTIONS PRECISION MEASUREMENT STATION Item No. 050078 The Hornady® Precision BILL OF MATERIALS Measurement Station allows the reloader to sort Item No. Part Number Description Qty. components according to size and 1 399750 Comparator Gauge Base 1 quality by comparing bullet ogive 2 399751 Indicator Shaft 1 location, cartridge base to ogive 3 399771 Case Shoulder Holder 1 location, headspace location and 4 399770 Case Head Holder 1 overall case length. In addition, this 5 399758 Comparator Holder 1 6 399762 BHCS, Flanged, 10-32 x 3/8 1 tool provides the reloader the ability 7 399210 BHCS, 10-32 x 1/4 4 to check true bullet to case 8 399759 Dial Indicator Flat Attachment 1 concentricity and identify 9 399764 1/4-20 Lock Nut 4 inconsistencies such as case and 10 399753 Indicator Holder 1 1 bullet dents. The base of the Hornady 11 399754 Indicator Holder 2 1 Precision Measurement Station 12 399763 #6-32 T-Slot Nut 2 weighs nearly eight pounds and has 13 398523 Dial Indicator .0005 1 leveling feet for stability. 14 399752 1/4-20 Rubber Leveling Foot 4 15 69100 Bullet Comparator .224 1 16 69101 Bullet Comparator .243 1 17 69103 Bullet Comparator .257 1 18 69102 Bullet Comparator .264 1 19 69105 Bullet Comparator .277 1 20 69104 Bullet Comparator .284 1 21 69106 Bullet Comparator .308 1 22 399765 8-32 Brass Thumb Screw 1 23 69006 Thumb Screw OAL Comp Headspace 4 24 69024 Headspace Bushing “A” (.330) 1 25 69025 Headspace Bushing “B” (.350) 1 26 69026 Headspace Bushing “C” (.375) 1 27 69027 Headspace Bushing “D” (.400) 1 28 69028 Headspace Bushing “E” (.420) 1 1 EXPLODED VIEW 13 8 22 23 28 21 27 26 10 25 11 24 23 20 19 23 7 18 4 2 17 23 16 6 15 12 5 3 1 9 14 2 CHANGING INDICATOR ATTACHMENTS (REFERENCE EXPLODED VIEW ON PG. -

Characterization of Volatile Organic Gunshot Residues in Fired Handgun Cartridges by Headspace Sorptive Extraction

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Serveur académique lausannois CHARACTERIZATION OF VOLATILE ORGANIC GUNSHOT RESIDUES IN FIRED HANDGUN CARTRIDGES BY HEADSPACE SORPTIVE EXTRACTION a* b a M. Gallidabino , F. S. Romolo , C. Weyermann a University of Lausanne, École des Sciences Criminelles, Institut de Police Scientifique, Bâtiment Batochime, 1015 Lausanne-Dorigny, Switzerland b Sapienza Università di Roma, Section of Legal Medicine, Department SAIMLAL, Viale Regina Elena 336, 00161 Roma, Italy Abstract In forensic investigation of firearm-related cases, determination of the residual amount of volatile compounds remaining inside a cartridge could be useful in estimating the time since its discharge. Published approaches are based on following the decrease of selected target compounds as a function of time by using solid phase micro-extraction (SPME). Naphthalene, as well as an unidentified decomposition product of nitrocellulose (referred to as “TEA2”), are usually employed for this purpose. However, reliability can be brought into ques- tion given their high volatility and the low reproducibility of the extracted procedure. In order to identify alternatives and therefore develop improved dating methods, an extensive study on the composition and variability of volatile residues in nine different types of cartridges was carried out. Analysis was performed using headspace sorptive extraction (HSSE), which is a more exhaustive technique compared to SPME. 166 compounds were identified (several of which for the first time), and it was observed that the final compositional characteristics of each residue were strongly dependent on its source. Variability of single identified compounds within and between different types of cartridge, as well as their evolution over time, were also studied. -

May 2, 2021, On-Line Auction (PDF)

May 2, 2021 Spring Sale (All Sessions) Lot Title Winning Bid Amount 1 Canada's V.C.'s Hardcover Book 95 2 Loyal She Remains A Pictoral History of Ontario 22.5 3 Mixed Lot Military Softcover Books 6 4 Canadian Military Register of Foreign Awards 16 5 Mixed Lot Air Force Books 40 6 Warman's Civil War Collectables 22.5 7 London News Coronation 1937 and Canadian Valour Books 6 9 Mixed Lot Military Books 11 10 Military Books 2 11 Military Books 3 12 Framed Badges & Flashes 6 13 Mixed Lot American Civil War Books 10 14 Vintage Tank Periscope Prism Lenses 6 16 Mixed Lot Military Books 14 17 Canadian Expeditionary Force 1914-1918 170 18 Badges of the Canadian Forces 27.5 19 Warman's WW2 Collectables 15 20 Mixed Lot Books 2 21 Royal Canadian Mint Canadian Military WW2. Toronto Star Archives WW2 Photo Calendar. 2 22 Mixed Lot Military Books 42.5 23 Military Books 2 24 Military Breeches 25 25 Military Books WW2 2 26 British Battles & Medals 6 27 History of the Canadian Forces 1914-19 12 28 Collector Guide to the Fairbain-Sykes Fighting Knife 65 29 Canadian At War 1939/45 8 30 Military Books 3 31 Mixed Lot Military Books 16 32 McGill Honour Roll 1914-1918 32.5 33 Bank of Montreal Record of Service 1914-1918 16 35 Honours & Awards Canadian Naval Forces WW2 55 36 Mixed Lot Military Books 2 37 British Gallantry Awards 2 38 Mixed Lot Military Books 8 39 Canadian Military Aircraft Manufacturer Photographs 6 40 Bank of Commerce WW2 Service Records 16 41 University of Toronto Roll of Service 1914-1918 16 42 Dominion of Canada Militia List 1917 16 43 Mixed -

Plant Ecology and Biostatistics

BSCBO- 203 B.Sc. II YEAR Plant Ecology and Biostatistics DEPARTMENT OF BOTANY SCHOOL OF SCIENCES UTTARAKHAND OPEN UNIVERSITY PLANT ECOLOGY AND BIOSTATISTICS BSCBO-203 BSCBO-203 PLANT ECOLOGY AND BIOSTATISTICS SCHOOL OF SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF BOTANY UTTARAKHAND OPEN UNIVERSITY Phone No. 05946-261122, 261123 Toll free No. 18001804025 Fax No. 05946-264232, E. mail [email protected] htpp://uou.ac.in UTTARAKHAND OPEN UNIVERSITY Page 1 PLANT ECOLOGY AND BIOSTATISTICS BSCBO-203 Expert Committee Prof. J. C. Ghildiyal Prof. G.S. Rajwar Retired Principal Principal Government PG College Government PG College Karnprayag Augustmuni Prof. Lalit Tewari Dr. Hemant Kandpal Department of Botany School of Health Science DSB Campus, Uttarakhand Open University Kumaun University, Nainital Haldwani Dr. Pooja Juyal Department of Botany School of Sciences Uttarakhand Open University, Haldwani Board of Studies Late Prof. S. C. Tewari Prof. Uma Palni Department of Botany Department of Botany HNB Garhwal University, Retired, DSB Campus, Srinagar Kumoun University, Nainital Dr. R.S. Rawal Dr. H.C. Joshi Scientist, GB Pant National Institute of Department of Environmental Science Himalayan Environment & Sustainable School of Sciences Development, Almora Uttarakhand Open University, Haldwani Dr. Pooja Juyal Department of Botany School of Sciences Uttarakhand Open University, Haldwani Programme Coordinator Dr. Pooja Juyal Department of Botany School of Sciences Uttarakhand Open University, Haldwani UTTARAKHAND OPEN UNIVERSITY Page 2 PLANT ECOLOGY AND BIOSTATISTICS BSCBO-203 Unit Written By: Unit No. 1-Dr. Pooja Juyal 1, 4 & 5 Department of Botany School of Sciences Uttarakhand Open University Haldwani, Nainital 2-Dr. Harsh Bodh Paliwal 2 & 3 Asst Prof. (Senior Grade) School of Forestry & Environment SHIATS Deemed University, Naini, Allahabad 3-Dr. -

[ EI"-Tros,;Ern:E Laboratory

L.Apt;tc7 9~Apr [ /~-2~ 3 1176 01326 7670 -c 12--' .... 15~831 'I - • T • H • E OHIO 6tf SfA1E UNIVERSm' 1 • • 1 j I.D. luralde A.l. biDet 1, I.J. Gupta • I.B. Menu P.B. Pathak .. L. Peters, Jr • 1.. The Ohio State UtIiYelIi.., 1 " I J EI"-troS,;ern:e laboratory j DIfI DrtncM .. a.ctricaI be-eriRt ,..It c...... ow. 4212 ~ ~. (11Sl-CB-18312ij) B1D1B ceoss SECTIOS Ji88-26565 .. STODIES/CO~PACT BilGE BESE1BCB F~n~l iepo~t \1 1 (Ohio State Dnh.) 66 P CSC1. 111 1 Qllclas 1 GJ/32 0154831 I ! t Pinal Report No. 716148-31 Grant No. NSG-1613 June 1988 llational Aeronautic; Mel Spaee AdaJftistratioa Langley Fc!~arch C~nter Ha~pton. VA 23665 san"1t .. ~- IINft ~AT1OII IL IIPOU ... 1& ......... .. ,.. .......... ~-- ..! JUDe ....1988 RADAR CROSS SECTIO. STUDIES/CtltPACT lWICE RESEARCH .. , ........,., W.D. Burnside. A.K. Dominek. I.J. Gupta. &"' .. .~ 716148-31 ..... - E.lI. Newman. P.H. Pathak and L ............ 00 ....___ ,...... Peters Jr. .......-n_____ The Ohio State University •. ElectroSclence Laboratory • .. c...ctICl_ ~ ... 1320 Kinnear Road to Columbus. Ohio 43212 .. NSG-1613 u. ---.op .&T,.. ................ c-. National Aeronautics---"-- and Space Adalnistration Fioal Report Langley Research Center Hampton. VA 2366S .. at.. ... ..,-- __ n_,._ This report represents • su.aary of the achlev~ents on Grant NSC-1613 betveen The Ohio State University and the National Aeronautics and Space Ad.lnistratlon flO. Kay 1, 1987 to April 30. 1988. The ..jor topic. associated vith this study are as follovs: 1. Electroaagnetic scattering analysis 2. Indoor scattering lleasureaent systeas 3. -

410 Shotgun Lever Action Winchester

410 Shotgun Lever Action Winchester Buy Winchester 9410 Lever-Action Shotgun. MSRP is $680. This rifle is in excellent condition and has been owned by me for the last 48 years. Comes in Blue and Stainless finish. On sale 20 Gauge Bolt Action Slug Shotgun And 410 Lever Action Shotgun Winchester You can order 20 Gauge Bolt Action Slug Shotgun And 410 Lever Action Shotgun W. In 1887, Browning introduced the Model 1887 Lever Action Repeating Shotgun, which loaded a fresh cartridge from its internal magazine by the operation of the action lever. Henry Repeating Arms Side Gate Lever Action Shotgun Walnut / Brass. 410 bore is the equivalent of 67 gauge when referring to normal shotgun gauges (10, 12, 16, 20, or 28). 2 1/2 inch shells. 410 GA, 20" [H018X-410] CA$1,299. Action: Lever. Individual. Henry Repeating Arms Lever Action Axe Blued / Walnut. One of the most commonly used manufacturers for a wide range of shooting needs, Winchester USA is an outstanding pick due to its reliability, consistency and durability. finish is starting to fade and crack image: vg: ithaca: 0: 50. It is also called “the experts gun” for good reasons. The product you are looking for Winchester 410 Lever Action Shotgun And Diamond Arms 410 Shotgun. The 24" barrel boasts a Buckhorn Rear sight with a white Triangle guide plus a Green Fiber-optic light gathering front sight. 410 shotgun. Winchester. At 50 yards the Federal and Winchester slugs. Suit new shotgun buy. Winchester Model 1887 Deluxe Lever Action Shotgun; J. 410 Winchester 9410 in the 1990s, nearly a decade later Marlin introduced a lever. -

A BILL to Regulate Assault Weapons, to Ensure That the Right to Keep and Bear Arms Is Not Unlimited, and for Other Purposes

SIL17927 S.L.C. 115TH CONGRESS 1ST SESSION S. ll To regulate assault weapons, to ensure that the right to keep and bear arms is not unlimited, and for other purposes. IN THE SENATE OF THE UNITED STATES llllllllll Mrs. FEINSTEIN (for herself, Mr. BLUMENTHAL, Mr. MURPHY, Mr. SCHU- MER, Mr. DURBIN, Mrs. MURRAY, Mr. REED, Mr. CARPER, Mr. MENEN- DEZ, Mr. CARDIN, Ms. KLOBUCHAR, Mr. WHITEHOUSE, Mrs. GILLI- BRAND, Mr. FRANKEN, Mr. SCHATZ, Ms. HIRONO, Ms. WARREN, Mr. MARKEY, Mr. BOOKER, Mr. VAN HOLLEN, Ms. DUCKWORTH, and Ms. HARRIS) introduced the following bill; which was read twice and referred to the Committee on llllllllll A BILL To regulate assault weapons, to ensure that the right to keep and bear arms is not unlimited, and for other purposes. 1 Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representa- 2 tives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, 3 SECTION 1. SHORT TITLE. 4 This Act may be cited as the ‘‘Assault Weapons Ban 5 of 2017’’. 6 SEC. 2. DEFINITIONS. 7 (a) IN GENERAL.—Section 921(a) of title 18, United 8 States Code, is amended— SIL17927 S.L.C. 2 1 (1) by inserting after paragraph (29) the fol- 2 lowing: 3 ‘‘(30) The term ‘semiautomatic pistol’ means any re- 4 peating pistol that— 5 ‘‘(A) utilizes a portion of the energy of a firing 6 cartridge to extract the fired cartridge case and 7 chamber the next round; and 8 ‘‘(B) requires a separate pull of the trigger to 9 fire each cartridge. 10 ‘‘(31) The term ‘semiautomatic shotgun’ means any 11 repeating shotgun that— 12 ‘‘(A) utilizes a portion of the energy of a firing 13 cartridge to extract the fired cartridge case and 14 chamber the next round; and 15 ‘‘(B) requires a separate pull of the trigger to 16 fire each cartridge.’’; and 17 (2) by adding at the end the following: 18 ‘‘(36) The term ‘semiautomatic assault weapon’ 19 means any of the following, regardless of country of manu- 20 facture or caliber of ammunition accepted: 21 ‘‘(A) A semiautomatic rifle that has the capac- 22 ity to accept a detachable magazine and any 1 of the 23 following: 24 ‘‘(i) A pistol grip. -

March/April 1982 3 Amer.Caii

PISTOLSMITHING AT IT'S FINEST TRAPPER GUN INC. SEND YOUR COMPLETE $2.00 FOR FULL COLOR CATALOG CUSTOM HANDGUN CENTER ~iii BULLSEYE HANDGUN ACCESSORIES NOW AVAILABLE - THE SAME TOOLING WE USE IN OUR SHOP BULLSEYE WHITE OUTLINE REAR SIGHT BLADES for KIT #7 Fits all Colt Python & Older Style Troopers @KIT #16 Fits Virginia Dragoon. Complete Colt or Ruger (will not blur out) Rev. Reduces DA & SA trigger pull up to tune-up kit reduces trigger pull up t045% 45% HORIZON, The newest in rear sights for Ruger handguns. Designed to get on target fast! KIT #B Browning Hi-Power. Reduces trigger pull @KIT #R-l Fits all Ruger Mini 14. Inc"reases up t045% & increases slide power 15% cycle rate by 20% ... reduces trigger pull by 20% SPRING KITS ... increases hammer strike by 20% ... an aid to KIT #1 Fits all new model Ruger Single Action extraction by 15% Revolvers: Complete tune up kit with new style KIT #9 Fits all Colt Government Models/70 Series Hammber shock. Included: Your choice of either Hardballer & Crown City Arms. Reduces trigger pull up to 45% & increases slide power 15% Hunting or T.rget Trigger Springs. Hunting Model @KIT #R-2 Fits all Colt AR 15 and M-16 rifles. reduces trigger pull up to 45%. Target Model Increase cycle rate by 20% ... increase hammer reduces trigger pull up to 60% KIT #9-A Fits all Colt Government Models/70 strike by 20% ... an aid to extraction by KIT #2 Fits all center/ire Colt Mark III Troopers & Series Hardballer & Crown City Arms - Target 15% Lawman Rev. -

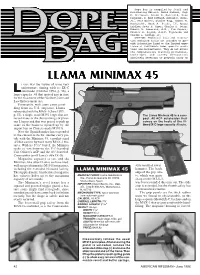

LLAMA MINIMAX 45 LAMA Was the Victim of Some Very Unfortunate Timing with Its IX-C Lautoloader (October 1994, P

Dope Bag is compiled by Staff and Contributing Editors: David Andrews, Hugh C. Birnbaum, Bruce N. Canfield, Russ Carpenter, O. Reid Coffield, William C. Davis, Jr., Pete Dickey, Charles Fagg, Robert W. Hunnicutt, Mark A. Keefe, IV, Angus Laidlaw, Scott E. Mayer, Charles E. Petty, Robert B. Pomeranz, O.D., Jim Supica, Charles R. Suydam, A.W.F. Taylerson and Stanton L. Wormley, Jr. CAUTION: Technical data and informa- tion contained herein are intended to pro- vide information based on the limited expe- rience of individuals under specific condi - tions and circumstances. They do not detail the comprehensive training procedures, techniques and safety precautions absolutely necessary to properly carry on ® LLAMA MINIMAX 45 LAMA was the victim of some very unfortunate timing with its IX-C Lautoloader (October 1994, p. 58), a large-capacity .45 that arrived just in time for the enactment of the Violent Crime and Law Enforcement Act. Fortunately, with some astute prod- ding from its U.S. importer, Llama rebounded with the MAX-1 (June 1995, p. 52), a single-stack M1911 type that cor- The Llama Minimax 45 is a com- rected many of the shortcomings of previ- pact .45 ACP autoloader that ous Llamas and that was priced to pick up comes on the heels of the ill- some of the business opened up by the timed IX-C large-capacity .45 auto. import ban on Chinese-made M1911s. Now the Spanish maker has responded to the current craze for smaller carry pis- tols with the Minimax 45, a pocket-sized .45 that carries forward many MAX-1 fea- 11 tures. -

GUNS Magazine March 2011

Enter To WIN!AT I GSG 19 11 $4.95 OUTSIDE U.S. $7.95 APRIL 2011 RangeRange IsIs Hot!Hot! SPRINGFIELD’SSPRINGFIELD’S RANGE OFFICER 1911 STOP THE MADNESS BRAKE THE BREAK-IN HABIT SHORT BARREL MAGIC RIFLE CARTRIDGE HANDGUNS Pg 18 AMMO SPECIAL! NEW PREMIUM & BUDGET LOADS Pg 77 CIRCUIT JUDGE .45 COLT/COLT/.410 CARBINECARBINE RIMFIRE SPECIAL • SAVAGE MODEL 93 .22 WMR • ACCURIZING THE RUGER 10/22 Pg 16 www.gunsmagazine.com A TRUE PAIR The most advanced training aid for Trap, Skeet And Sporting Clay Shooters alike “see where you are missing.” The Fiocchi Chemical Tracer powered by Cyalume, provides a daytime visible trace that travels with the cloud of shot as it hits or misses the clay bird.The Chemical Tracer is non-incendiary, non-toxic and meets EPA and Consumer Safety compliance. It leaves no residue in the barrel and is non-corrosive. The 12 Gauge 3/4 oz #8 shot + Cyalume Tracer Load is light sensitive and is therefore packaged as part of the New and Innovative Fiocchi ‘Canned Heat’ Line. The Fiocchi Chemical Tracer “see where you are missing” SINCE 1876 For the Fiocchi dealer near you, Call 417.449.1043 / visit www.fiocchiusa.com APRIL 2011 Vol. 57, Number 4, 665th Issue COLUMNS CROSSFIRE 6 LEttERS tO thE EdItOR RANGING SHOTS™ 8 CLINt SMIth HANDGUNS 1 2 MASSAd AyOOb GUNSMITHING H 1 6 AMILtON S. bOWEN 18 HANDLOADING 84 ENtER tO WIN! JOhN bARSNESS AMERICAN TACTICAL IMPORTS MONTANA MUSINGS 2 2 MIkE “dUkE” VENtURINO GSG 1911 .22 LONG RIFLE 2 4 OPTICS JACOb GOttfREdSON 8 RIFLEMAN Dave28 ANdERSON SHOTGUNNER Hol 3 0 t bOdINSON 6 0 KNIVES DEPARTMENTS A P t COVERt 34 OUT OF THE BOX™ 6 2 VIEWS, NEWS & REVIEWS SAVAGE MOdEL 93 .22 WMR RIGhtS WAtCh: David COdREA 36 SURPLUS LOCKER™ 86 ODD ANGRY SHOT Holt bOdINSON JOhN CONNOR 40 QUESTIONS & ANSWERS 9 0 CAMPFIRE TALES JEff JOhN JOhN TaffIN 74 CATALOG SHOWCASE 77 QUARTERMASTER 12 FeatURING GUNS ALLStARS! THIS MONTH: • JOhN CONNOR GUNS Magazine (ISSN 1044-6257) is published monthly by Publishers’ Development Corpora- tion, 12345 World Trade Drive, San Diego, CA 92128.