8 Language Change and Endangerment in West Java

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made from the Ori Inal Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 481 305 FL 027 837 AUTHOR Lo Bianco, Joseph, Ed. TITLE Voices from Phnom Penh. Development & Language: Global Influences & Local Effects. ISBN ISBN-1-876768-50-9 PUB DATE 2002-00-00 NOTE 362p. AVAILABLE FROM Language Australia Ltd., GPO Box 372F, Melbourne VIC 3001, Australia ($40). Web site: http://languageaustralia.com.au/. PUB TYPE Books (010) Collected Works Proceedings (021) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC15 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *College School Cooperation; Community Development; Distance Education; Elementary Secondary Education; *English (Second Language); Ethnicity; Foreign Countries; Gender Issues; Higher Education; Indigenous Populations; Intercultural Communication; Language Usage; Language of Instruction; Literacy Education; Native Speakers; *Partnerships in Education; Preservice Teacher Education; Socioeconomic Status; Student Evaluation; Sustainable Development IDENTIFIERS Cambodia; China; East Timor; Language Policy; Laos; Malaysia; Open q^,-ity; Philippines; Self Monitoring; Sri Lanka; Sustainability; Vernacular Education; Vietnam ABSTRACT This collection of papers is based on the 5th International Conference on Language and Development: Defining the Role of Language in Development, held in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, in 2001. The 25 papers include the following: (1) "Destitution, Wealth, and Cultural Contest: Language and Development Connections" (Joseph Lo Bianco); (2) "English and East Timor" (Roslyn Appleby); (3) "Partnership in Initial Teacher Education" (Bao Kham and Phan Thi Bich Ngoc); (4) "Indigenous -

Chapter 1 Introduction

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background of the study Language is primary tool for communicating. Every language has several entities that may not be owned by the other languages, on the other word, language is special and unique. The uniqueness of the language is strongly influenced by the culture of native speaker. Therefore, the language varies cross-culturally. Language also become a tool for social interaction whereas every interlocutor has their own style that can be heard when doing conversation. Moreover, the manner of conversation that is done by people is an important thing that should be more considered. According to Yule (1996), people who involved in interaction indirectly make the norms and principles that arise in the community as their politeness standards (Yule, 1996). Language often expresses the speaker's identity, as well as regional languages in Indonesia such Betawinese, Javanese, Sundanese etc. According to research that was conducted by The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) found more than a hundred of regional languages in Indonesia have been extinct. One of regional languages that still exist today is Betawi language, which is almost as old as the name of the area where the language is developed, Jakarta. Formed since the 17th century, Jakarta has various ethnicities, races, and social backgrounds, and the original community uses Betawi language as their language of daily life . Betawi language is derived from Malay, and so many Sumatra or Malay Malaysian terms are used in Betawi. One example is the word "Niari" which means today or “hari ini” in Indonesian. Although there are similarities with the Malay Malaysian, but this language has been mixed with foreign languages, such as Dutch, Portuguese, Arabic, Chinese, Bugis, Sumatera and many other languages (Muhadjir, 2000). -

116 LANGUAGE AWARENESS: LANGUAGE USE and REASONS for CODE-SWITCHING Cresensiana Widi Astuti STIKS Tarakanita Jakarta, Indonesia

LLT Journal, e-ISSN 2579-9533, p-ISSN 1410-7201, Vol. 23, No. 1, April 2020 LLT Journal: A Journal on Language and Language Teaching http://e-journal.usd.ac.id/index.php/LLT Sanata Dharma University, Yogyakarta, Indonesia LANGUAGE AWARENESS: LANGUAGE USE AND REASONS FOR CODE-SWITCHING Cresensiana Widi Astuti STIKS Tarakanita Jakarta, Indonesia correspondence: [email protected] DOI: doi.org/10.24071/llt.2020.230109 received 4 January 2020; accepted 26 March 2020 Abstract The co-existence of languages in a speech community prompts language users to do code-switching in communication. They do it for certain reasons. This paper is to report language awareness among language users and the reasons why people do code-switching in their speech communities. Using an open-ended questionnaire, this research involved 50 participants. They were asked to identify the languages they had in their repertoire, the language they used when they communicate with certain people, and the reasons why they did code-switching in communication. The results showed that, first, the participants had awareness of languages in their repertoire, namely Indonesian, a local language, and English. Second, they admitted that they did code-switching in communication. Thirdly, the reasons for code- switching were to discuss a particular topic, to signal a change of dimension, to signal group membership, and to show affective functions. Keywords: language awareness, language use, code-switching reasons Introduction It is common nowadays to find several languages used in a speech community. When people communicate in a speech community, they are usually aware of the language they should use in communication with other people. -

Torch Light in the City: Auto/Ethnographic Studies of Urban Kampung Community in Depok City, West Java1

Torch light in the city: Auto/Ethnographic Studies of Urban Kampung Community in Depok City, West Java1 Hestu Prahara Department of Anthropology, University of Indonesia “Di kamar ini aku dilahirkan, di bale bambu buah tangan bapakku. Di rumah ini aku dibesar- kan, dibelai mesra lentik jari ibuku. Nama dusunku Ujung Aspal Pondokgede. Rimbun dan anggun, ramah senyum penghuni dusunku. Sampai saat tanah moyangku tersentuh sebuah rencana demi serakahnya kota. Terlihat murung wajah pribumi… Angkuh tembok pabrik berdiri. Satu persatu sahabat pergi dan takkan pernah kembali” “In this room I was born, in a bamboo bed made by my father’s hands. In this house I was raised, caressed tenderly by my mother’s hands. Ujung Aspal Pondokgede is the name of my village. She is lush and graceful with friendly smile from the villagers. Until then my ancestor’s land was touched by the greedy plan of the city. The people’s faces look wistful… Factory wall arrogantly stood. One by one best friends leave and will never come back” (Iwan Fals, Ujung Aspal Pondokgede) Background The economic growth and socio-spatial trans- an important role as a buffer zone for the nucleus. formation in Kota Depok cannot be separated Demographically speaking, there is a tendency of from the growth of the capital city of Indonesia, increasing population in JABODETABEK area DKI Jakarta. Sunarya (2004) described Kota from time to time. From the total of Indonesian Depok as Kota Baru (new city) of which its socio- population, 3 percent live in satellite cities of economic transformations is strongly related to Jakarta area in 1961, increased by 6 percent in the development of greater Jakarta metropolitan. -

Buku Profil Anggota DPRD Kabupaten Tangerang

PROFIL ANGGOTA DEWAN PERWAKILAN RAKYAT DAERAH KABUPATEN TANGERANG PERIODE 2014 – 2019 KOMISI PEMILIHAN UMUM KABUPATEN TANGERANG DAERAH PEMILIHAN TANGERANG 1 Kecamatan : BALARAJA JAYANTI TIGARAKSA JAMBE CISOKA SOLEAR JUMLAH KURSI : 9 JUMLAH SUARA SAH : 240,349 ANGKA BILANGAN PEMBAGI PEMILIH (BPP) : 26,705 Halaman 1 PROFIL ANGGOTA DEWAN PERWAKILAN RAKYAT DAERAH KABUPATEN TANGERANG PERIODE 2014 – 2019 KOMISI PEMILIHAN UMUM KABUPATEN TANGERANG NAMA : BURHAN TEMPAT/TANGGAL LAHIR : Jakarta, , 02 September 1975 ALAMAT : Taman Kirana Surya Rt. 006/08 Pasanggrahan Solear AGAMA : ISLAM JENIS KELAMIN : LAKI-LAKI STATUS PERKAWINAN : MENIKAH NAMA ISTERI/SUAMI : AWALIYANTI JUMLAH ANAK : 2 PEKERJAAN : SWASTA/PEKERJAAN LAINNYA RIWAYAT PENDIDIKAN : - SEKOLAH DASAR : 1981-1987, SD, SDN 06 PASEBAN, JAKARTA PUSAT - SEKOLAH MENENGAH PERTAMA : 1987-1990, SLTP, SMPN 1 BALARAJA, TANGERANG - SEKOLAH MENENGAH ATAS : 1990-1993, SLTA, SMAN 1 BALARAJA, TANGERANG - PERGURUAN TINGGI : - RIWAYAT ORGANISASI : - RIWAYAT PEKERJAAN : - PARTAI : PKB NOMOR URUT : 2 DAPIL : Tangerang 1 (satu) SUARA CALON : 2293 SUARA PARTAI : 14718 KUOTA KURSI : 26705 SUARA Halaman 2 PROFIL ANGGOTA DEWAN PERWAKILAN RAKYAT DAERAH KABUPATEN TANGERANG PERIODE 2014 – 2019 KOMISI PEMILIHAN UMUM KABUPATEN TANGERANG NAMA : SURYANI ANYA, S.Sos TEMPAT/TANGGAL LAHIR : Tangerang, 02 Maret 1990 ALAMAT : Kp. Saredang Rt. 002/003 Matagara Tigaraksa AGAMA : ISLAM JENIS KELAMIN : PEREMPUAN STATUS PERKAWINAN : BELUM MENIKAH NAMA ISTERI/SUAMI : JUMLAH ANAK : PEKERJAAN : WIRASWASTA RIWAYAT PENDIDIKAN : - SEKOLAH -

Implementasi Program Tangerang Berkebun Di Kecamatan Pinang Dan Kecamatan Karang Tengah

IMPLEMENTASI PROGRAM TANGERANG BERKEBUN DI KECAMATAN PINANG DAN KECAMATAN KARANG TENGAH SKRIPSI Diajukan sebagai Salah Satu Syarat untuk Memperoleh Gelar Sarjana Ilmu Administrasi Publik pada Konsentrasi Kebijakan Publik Program Studi Ilmu Administrasi Publik Oleh Dhani Chairani 6661110960 FAKULTAS ILMU SOSIAL DAN ILMU POLITIK UNIVERSITAS SULTAN AGENG TIRTAYASA SERANG, 2018 MOTTO DAN PERSEMBAHAN Motto “It always seems impossible until it’s done.” — Nelson Mandela Persembahan “Dengan penuh cinta dan sebagai bentuk terima kasih, ku persembahkan skripsi ini untuk Mama dan Papa yang tidak pernah lelah mendoakan dan dengan sabar memahamiku. Serta untuk adikku agar tidak berhenti menuntut ilmu.” ABSTRAK Dhani Chairani. NIM: 6661110960. Skripsi. Implementasi Program Tangerang Berkebun Di Kecamatan Pinang dan Kecamatan Karang Tengah. Program Studi Ilmu Administrasi Publik. Fakultas Ilmu Sosial dan Ilmu Politik. Universitas Sultan Ageng Tirtayasa. Pembimbing I: Dr. Agus Sjafari, M.Si. Pembimbing II: Dr. Gandung Ismanto, M.M. Tangerang Berkebun adalah program yang dicanangkan oleh Dinas Ketahanan Pangan Kota Tangerang untuk mengembangkan sektor pertanian dengan cara menerapkan sistem pertanian perkotaan dengan tujuan untuk pemenuhan gizi keluarga. Pada pelaksanaannya, penyelenggaraan Program Tangerang Berkebun di Kecamatan Pinang dan Kecamatan Karang Tengah menemui berbagai permasalahan seperti tidak dilibatkannya petani lokal pada Program Tangerang Berkebun; waktu pembinaan masyarakat yang terbilang singkat; kurangnya minat dan motivasi masyarakat untuk membudidayakan tanaman; dan belum dilibatkannya kaum muda pada penyelenggaraan Program Tangerang Berkebun. Untuk mengkaji permasalahan yang muncul, peneliti menggunakan teori implementasi publik menurut Van Metter Van Horn. Tujuan penelitian ini untuk mengetahui pelaksanaan program tersebut dan faktor-faktor apa saja yang menghambat pelaksanaannya. Penelitian ini menggunakan metode kualitatif deskriptif dan peneliti bertindak sebagai instrumen penelitian. -

Daftar-Nama-Sekolah-Geo-Tagging.Pdf

DAFTAR NAMA SEKOLAH YANG AKAN DIKUNJUNGI TIM PUSAT DALAM RANGKA PENGAMBILAN CITRA (GEO TAGGING) NO. NPSN NAMA ALAMAT KELURAHAN KECAMATAN JENJANG 1 20604549 SDN BALARAJA I JL. RAYA SERANG KM. 24 BALARAJA BALARAJA SD 2 20604550 SDN BALARAJA II JL. RAYA KRESEK KP. ILAT BALARAJA BALARAJA SD 3 20604551 SDN BALARAJA III JL. RAYA KRESEK KM. 0,5 BALARAJA BALARAJA SD 4 20602767 SDN SAGA I JL. DS. BUNAR SAGA BALARAJA SD 5 20602768 SDN SAGA II JL. KP. PEKONG SAGA BALARAJA SD 6 20602769 SDN SAGA III JL. DS. BUNAR SAGA BALARAJA SD 7 20602770 SDN SAGA IV JL. BUNAR SAGA BALARAJA SD 8 20603417 SDN TALAGASARI I JL. RAYA SERANG KM. 24 TALAGASARI BALARAJA SD 9 20603433 SDN TALAGASARI II JL. RAYA SERANG KM.23,5 TALAGASARI BALARAJA SD 10 20615513 SDLB NEGERI 01 KABUPATEN TANGERANG JL. CARINGIN II RT. 02/02 SAGA BALARAJA SLB 11 69726949 SMPLB NEGERI 01 KABUPATEN TANGERANG JL. CARINGIN II RT. 02/02 SAGA BALARAJA SLB 12 20613465 SMAN 19 KABUPATEN TANGERANG JL. RAYA KRESEK KM 1,5 SAGA BALARAJA SMA 13 20622268 SMKS AL - BADAR JL. RAYA GEMBONG - CARIU KP. DANGDEUR SUKAMURNI BALARAJA SMK 14 20613680 SMKS TUNAS HARAPAN BALARAJA JL. RAYA BUNAR SAGA BALARAJA SMK 15 20623129 SMKS YAMITEC JL. RAYA SERANG KM. 30 GEMBONG BALARAJA SMK 16 20603156 SMPN 3 BALARAJA JL. SENTUL JAYA KM. 03 TOBAT BALARAJA SMP 17 20614344 SMPS AL BADAR DANGDEUR JL. GEMBONG CARIU DS. SUKAMURNI KEC KRESEK SUKAMURNI BALARAJA SMP 18 20616552 SDS ISLAM AZZAHRO JL. RAYA SERANG KM. 13 KP. CIREWED SUKADAMAI CIKUPA SD 19 20613492 SDLBS SAHIDA CIKUPA JL. -

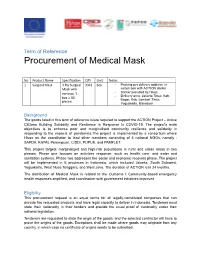

Term of Reference Procurement of Medical Mask

Term of Reference Procurement of Medical Mask No Product Name Specificaon QTY Unit Notes 1 Surgical Mask 3 Ply Surgical 3341 box - Packing per delivery address in Mask with carton box with ACTION sticker earloop; 1 - Sticker provided by Hivos - Delivery area: Jakarta Timur, Kab. box = 50 Bogor, Kab. Lombok Timur, pieces Yogyakarta, Makassar Background The goods listed in this term of reference is/are required to support the ACTION Project – Active Citizens Building Solidarity and Resilience in Response to COVID-19. The project’s main objectives is to enhance poor and marginalised community resilience and solidarity in responding to the impacts of pandemics.The project is implemented by a consortium where Hivos as the coordinator to lead other members consisting of 5 national NGOs, namely : SAPDA, KAPAL Perempuan, CISDI, PUPUK, and PAMFLET. This project targets marginalized and high-risk populations in rural and urban areas in two phases. Phase one focuses on activities response, such as health care, and water and sanitation systems. Phase two addresses the social and economic recovery phase. The project will be implemented in 5 provinces in Indonesia, which included Jakarta, South Sulawesi, Yogyakarta, West Nusa Tenggara, and West Java. The duration of ACTION is in 24 months. The distribution of Medical Mask is related to the Outcome I: Community-based emergency health responses amplified, and coordination with government initiatives improved Eligibility This procurement request is on equal terms for all legally-constituted companies that can provide the requested products and have legal capacity to deliver in Indonesia. Tenderers must state their nationality in their tenders and provide the usual proof of nationality under their national legislation. -

Seminar Nasional / National Seminar

PROGRAM BOOK PIT5-IABI 2018 PERTEMUAN ILMIAH TAHUNAN (PIT) KE-5 RISET KEBENCANAAN 2018 IKATAN AHLI KEBENCANAN INDONESIA (IABI) 5TH ANNUAL SCIENTIFIC MEETING – DISASTER RESEARCH 2018 INDONESIAN ASSOCIATION OF DISASTER EXPERTS (IABI) . SEMINAR NASIONAL / NATIONAL SEMINAR . INTERNASIONAL CONFERENCE ON DISASTER MANAGEMENT (ICDM) ANDALAS UNIVERSITY PADANG, WEST SUMATRA, INDONESIA 2-4 MAY 2018 PROGRAM BOOK PIT5-IABI 2018 Editor: Benny Hidayat, PhD Nurhamidah, MT Panitia sudah berusaha melakukan pengecekan bertahap terhadap kesalahan ketik, judul makalah, dan isi buku program ini sebelum proses pencetakan buku. Jika masih terdapat kesalahan dan kertinggalan maka panitia akan perbaiki di versi digital buku ini yang disimpan di website acara PIT5-IABI. The committee has been trying to check the typos and the contents of this program book before going to the book printing process. If there were still errors and omissions then the committee will fix it in the digital version of this book which is stored on the website of the PIT5-IABI event. Doc. Version: 11 2 PIT5-IABI OPENING REMARK FROM THE RECTOR Dear the International Conference on Disaster Management (ICDM 2018) and The National Conference of Disaster Management participants: Welcome to Andalas University! It is our great honor to host the very important conference at our green campus at Limau Manis, Padang. Andalas University (UNAND) is the oldest university outside of Java Island, and the fourth oldest university in Indonesia. It was officially launched on 13 September 1956 by our founding fathers Dr. Mohammad Hatta, Indonesia first Vice President. It is now having 15 faculties and postgraduate program and is home for almost 25000 students. -

LEMBARAN DAERAH KOTA TANGERANG Nomor 5 Tahun 2000

LEMBARAN DAERAH KOTA TANGERANG Nomor 5 Tahun 2000 Seri C PERATURAN DAERAH KOTA TANGERANG NOMOR 23 TAHUN 2000 T E N T A N G RENCANA TATA RUANG WILAYAH DENGAN RAHMAT TUHAN YANG MAHA ESA WALIKOTA TANGERANG Menimbang : a. bahwa untuk mengarahkan pembangunan di Kota Tangerang dengan memanfaatkan ruang wilayah secara serasi, selaras, seimbang, berdaya guna, berhasil guna, berbudaya dan berkelanjutan dalam rangka meningkatkan kesejahteraan masyarakat yang berkeadilan dan pertahanan keamanan, perlu disusun Rencana Tata Ruang Wilayah; b. bahwa dalam rangka mewujudkan keterpaduan pembangunan antar sektor, daerah, dan masyarakat, maka Rencana Tata Ruang Wilayah merupakan arahan dalam pemanfaatan ruang bagi semua kepentingan secara terpadu yang dilaksanakan secara bersama oleh pemerintah, masyarakat, dan/atau dunia usaha; c. bahwa dengan berlakunya Undang-undang Nomor 24 Tahun 1992 tentang Penataan Ruang dan Peraturan Pemerintah Nomor 47 Tahun 1997 tentang Rencana Tata Ruang Wilayah Nasional, maka strategi dan arahan kebijakan pemanfaatan ruang wilayah nasional perlu dijabarkan ke dalam Rencana Tata Ruang Wilayah Kota Tangerang; d. bahwa Peraturan Daerah Kotamadya Daerah Tingkat II Tangerang Nomor 19 Tahun 1994 tentang Rencana Tata Ruang Wilayah Kotamadya Daerah Tingkat II Tangerang tidak sesuai lagi dengan perkembangan keadaan sehingga perlu di ganti; e. bahwa berdasarkan pertimbangan pada huruf a, b, c dan d, maka perlu menetapkan Rencana Tata Ruang Wilayah Kota Tangerang dengan Peraturan Daerah. 2 Mengingat : 1. Undang-undang Nomor 8 Tahun 1981 tentang Kitab Undang- undang Hukum Acara Pidana (Lembaran Negara Tahun 1981 Nomor 76, TLN Nomor 3209); 2. Undang-undang Nomor 24 Tahun 1992 tentang Penataan Ruang (Lembaran Negara Nomor 1992 Nomor 115, TLN Nomor 5301); 3. -

Lahan Pertanian Abadi (Lpa) Di Kabupaten Tangerang

LAHAN PERTANIAN ABADI (LPA) DI KABUPATEN TANGERANG Yunita Ismail President University, Jababeka Education Park, Jln. Kihajar Dewantara Kota Jababeka, Bekasi 17550, Indonesia [email protected] ABSTRACT Tangerang regency is a supporting area for DKI Jakarta. The main function of this supporting area is as the human resource for fulfilling development needs of DKI Jakarta. Based on agricultural products from Tangerang regency, it is known that rice production almost 12 tons GKP/ha/year. This production is big enough to support harvest production nationally. Therefore, changing in dedicated agricultural field to be a non- agricultural area is considered will decrease rice production in Tangerang regency. Based on those conditions, it is needed to decide agricultural field which will not be used for non-agricultural activities, or so called agricultural land conversion (LPA). This research uses secondary data from Biro Pusat Statistik (Indonesia bureau of statistic) in Tangerang regency. The conclusion is that controlling the agricultural land conversion based on land capability survey in LPA area, as detail survey to irrigated rice field, non-irrigated rice field, and deep observation for agricultural field non-rice field. Keywords: LPA (agricultural land conversion), Tangerang, agricultural, rice production ABSTRAK Kabupaten Tangerang merupakan daerah penyangga bagi DKI Jakarta. Fungsi daerah penyangga yang paling utama adalah sebagai sumber tenaga kerja untuk memenuhi kebutuhan pembangunan DKI Jakarta. Dilihat dari hasil pertanian dari Kabupaten Tangerang, didapat bahwa produksi padi mencapai 12 ton GKP/ha/tahun. Produksi ini cukup besar untuk menunjang produksi panen secara nasional. Karenanya, perubahan peruntukan lahan pertanian menjadi untuk non pertanian dikhawatirkan akan menurunkan produksi padi di Kabupaten Tangerang. -

Lembaran Daerah Kabupaten Tangerang Nomor 13 Tahun

LEMBARAN DAERAH KABUPATEN TANGERANG NOMOR 13 TAHUN 2011 PERATURAN DAERAH KABUPATEN TANGERANG NOMOR 13 TAHUN 2011 TENTANG RENCANA TATA RUANG WILAYAH KABUPATEN TANGERANG TAHUN 2011-2031 DENGAN RAHMAT TUHAN YANG MAHA ESA BUPATI TANGERANG , Menimbang : a. bahwa berdasarkan Undang-Undang Nomor 26 Tahun 2007 tentang Penataan Ruang Pasal 78 ayat (4) huruf c mengamanatkan penyusunan atau penyesuaian Peraturan Daerah tentang Rencana Tata Ruang Wilayah Kabupaten; b. bahwa rencana tata ruang Kabupaten Tangerang sebagaimana diatur dalam Peraturan Daerah Kabupaten Daerah Tingkat II Tangerang Nomor 3 Tahun 1996 tentang Rencana Tata Ruang Wilayah Kabupaten Tangerang sebagaimana telah dua kali diubah terakhir dengan Peraturan Daerah Nomor 3 Tahun 2008 tentang Perubahan Kedua atas Peraturan Daerah Kabupaten Daerah Tingkat II Tangerang Nomor 3 Tahun 1996 tentang Rencana Tata Ruang Wilayah Kabupaten Tangerang tidak sesuai lagi dengan perkembangan sosial, ekonomi, politik, lingkungan regional , dan global, sehingga berdampak pada penurunan kualitas ruang di Kabupaten Tangerang; c. bahwa penataan ruang dilakukan sesuai kaidah - kaidah perencanaan yang mencakup azas keselarasan, keserasian, keterpaduan, kelestarian, keberlanjutan, serta keterkaitan antarwilayah; d. bahwa ... -2- d. bahwa berdasarkan pertimbangan sebagaimana dimaksud pada huruf a, huruf b, dan huruf c, perlu menetapkan Peraturan Daerah tentang Rencana Tata Ruang Wilayah Kabupaten Tangerang; Mengingat : 1. Pasal 18 ayat (6) Undang–Undang Dasar Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 1945; 2. Undang–Undang Nomor 14 Tahun 1950 tentang Pembentukan Daerah-Daerah Kabupaten Dalam Lingkungan Provinsi Jawa Barat (Berita Negara Tahun 1950); 3. Undang–Undang Nomor 5 Tahun 1960 tentang Peraturan Dasar Pokok–Pokok Agraria (Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 1960 Nomor 104 Tambahan Lembaran Negara Nomor 2043); 4. Undang-Undang Nomor 5 Tahun 1984 tentang Perindustrian (Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Tahun 1984 Nomor 22 Tambahan Lembaran Negara Republik Indonesia Nomor 3274); 5.