Partitive Noun Phrases in Hungarian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Strategy of Case-Marking

Case marking strategies Helen de Hoop & Andrej Malchukov1 Radboud University Nijmegen DRAFT January 2006 Abstract Two strategies of case marking in natural languages are discussed. These are defined as two violable constraints whose effects are shown to converge in the case of differential object marking but diverge in the case of differential subject marking. The strength of the case bearing arguments will be shown to be of utmost importance for case marking as well as voice alternations. The strength of arguments can be viewed as a function of their discourse prominence. The analysis of the case marking patterns we find cross-linguistically is couched in a bidirectional OT analysis. 1. Assumptions In this section we wish to put forward our three basic assumptions: (1) In ergative-absolutive systems ergative case is assigned to the first argument x of a two-place relation R(x,y). (2) In nominative-accusative systems accusative case is assigned to the second argument y of a two-place relation R(x,y). (3) Morphologically unmarked case can be the absence of case. The first two assumptions deal with the linking between the first (highest) and second (lowest) argument in a transitive sentence and the type of case marking. For reasons of convenience, we will refer to these arguments quite sloppily as the subject and the object respectively, although we are aware of the fact that the labels subject and object may not be appropriate in all contexts, dependent on how they are actually defined. In many languages, ergative and accusative case are assigned only or mainly in transitive sentences, while in intransitive sentences ergative and accusative case are usually not assigned. -

Nouns, Verbs and Sentences 98-348: Lecture 2 Any Questions About the Homework? Everyone Read One Word

Nouns, Verbs, and Sentences 98-348: Lecture 2 Nouns, verbs and sentences 98-348: Lecture 2 Any questions about the homework? Everyone read one word • Þat var snimma í ǫndverða bygð goðanna, þá er goðin hǫfðu sett Miðgarð ok gǫrt Valhǫ́ll, þá kom þar smiðr nǫkkurr ok bauð at gøra þeim borg á þrim misserum svá góða at trú ok ørugg væri fyrir bergrisum ok hrímþursum, þótt þeir kœmi inn um Miðgarð; en hann mælti sér þat til kaups, at hann skyldi eignask Freyju, ok hafa vildi hann sól ok mána. How do we build sentences with words? • English • The king slays the serpent. • The serpent slays the king. • OI • Konungr vegr orm. king slays serpent (What does this mean?) • Orm vegr konugr. serpent slays king (What does this mean?) How do we build sentences with words? • English • The king slays the serpent. • The serpent slays the king. They have the • OI same meaning! • Konungr vegr orm. But why? king slays serpent ‘The king slays the serpent.’ • Orm vegr konugr. serpent slays king ‘The king slays the serpent.’ Different strategies to mark subjects/objects • English uses word order: (whatever noun) slays (whatever noun) This noun is a subject! This noun is a subject! • OI uses inflection: konung r konung This noun is a subject! This noun is an object! Inflection • Words change their forms to encode information. • This happens in a lot of languages! • English: • the kid one kid • the kids more than one kid • We say that English nouns inflect for number, i.e. English nouns change forms based on what number they have. -

The Term Declension, the Three Basic Qualities of Latin Nouns, That

Chapter 2: First Declension Chapter 2 covers the following: the term declension, the three basic qualities of Latin nouns, that is, case, number and gender, basic sentence structure, subject, verb, direct object and so on, the six cases of Latin nouns and the uses of those cases, the formation of the different cases in Latin, and the way adjectives agree with nouns. At the end of this lesson we’ll review the vocabulary you should memorize in this chapter. Declension. As with conjugation, the term declension has two meanings in Latin. It means, first, the process of joining a case ending onto a noun base. Second, it is a term used to refer to one of the five categories of nouns distinguished by the sound ending the noun base: /a/, /ŏ/ or /ŭ/, a consonant or /ĭ/, /ū/, /ē/. First, let’s look at the three basic characteristics of every Latin noun: case, number and gender. All Latin nouns and adjectives have these three grammatical qualities. First, case: how the noun functions in a sentence, that is, is it the subject, the direct object, the object of a preposition or any of many other uses? Second, number: singular or plural. And third, gender: masculine, feminine or neuter. Every noun in Latin will have one case, one number and one gender, and only one of each of these qualities. In other words, a noun in a sentence cannot be both singular and plural, or masculine and feminine. Whenever asked ─ and I will ask ─ you should be able to give the correct answer for all three qualities. -

Genitive Constructions in Coptic Barbara Egedi

Genitive constructions in Coptic Barbara Egedi 1. Introduction 1.1. Definition of ‘Coptic’ Coptic is the language of Christian Egypt (4th to 14th century) written in a specific version of the Greek alphabet. It was gradually superseded by Ara- bic from the ninth century onward, but it survived to the present time as the liturgical language of the Christian church of Egypt. In this paper I examine only one of its main dialects, the Sahidic Coptic and I use a transcription which simply reflects the Coptic letters irrespectively of phonological de- tails.1 1.2. UG in the reconstruction of dead languages Natural languages are claimed to have universal properties or principles which constitute what is referred to as Universal Grammar. Accepting cer- tain universal principles and observing the corresponding parameters in Coptic, we can also analyse a language without living native speakers, and explain its structural relations with the help of coherent models. For example, it is considered a universal principle that the projections of lexical heads are extended by one or more functional projections. If we assume that it can be demonstrated in many languages, why could not we suppose the same in the case of Coptic? Indeed, as it will be shown in chap- ter 4, there are at least two functional projections above Coptic lexical noun phrase as well. The aim of this paper is to provide an adequate account of the basic structure of the Coptic NP within the theoretical framework of the Mini- malist Program (a short summary of which will be found in the following section); at the same time, I intend to find the answer to unsolved questions related to genitive constructions. -

Introduction to Gothic

Introduction to Gothic By David Salo Organized to PDF by CommanderK Table of Contents 3..........................................................................................................INTRODUCTION 4...........................................................................................................I. Masculine 4...........................................................................................................II. Feminine 4..............................................................................................................III. Neuter 7........................................................................................................GOTHIC SOUNDS: 7............................................................................................................Consonants 8..................................................................................................................Vowels 9....................................................................................................................LESSON 1 9.................................................................................................Verbs: Strong verbs 9..........................................................................................................Present Stem 12.................................................................................................................Nouns 14...................................................................................................................LESSON 2 14...........................................................................................Strong -

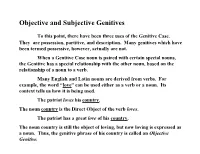

Objective and Subjective Genitives

Objective and Subjective Genitives To this point, there have been three uses of the Genitive Case. They are possession, partitive, and description. Many genitives which have been termed possessive, however, actually are not. When a Genitive Case noun is paired with certain special nouns, the Genitive has a special relationship with the other noun, based on the relationship of a noun to a verb. Many English and Latin nouns are derived from verbs. For example, the word “love” can be used either as a verb or a noun. Its context tells us how it is being used. The patriot loves his country. The noun country is the Direct Object of the verb loves. The patriot has a great love of his country. The noun country is still the object of loving, but now loving is expressed as a noun. Thus, the genitive phrase of his country is called an Objective Genitive. You have actually seen a number of Objective Genitives. Another common example is Rex causam itineris docuit. The king explained the cause of the journey (the thing that caused the journey). Because “cause” can be either a noun or a verb, when it is used as a noun its Direct Object must be expressed in the Genitive Case. A number of Latin adjectives also govern Objective Genitives. For example, Vir miser cupidus pecuniae est. A miser is desirous of money. Some special nouns and adjectives in Latin take Objective Genitives which are more difficult to see and to translate. The adjective peritus, -a, - um, meaning “skilled” or “experienced,” is one of these: Nautae sunt periti navium. -

Nominative and Objective Cases Reteaching

Name Date Lesson 1 Nominative and Objective Cases Reteaching Personal pronouns change form depending on how they function in a sentence. The form of a pronoun is called its case. The cases are nominative, objective, and possessive. Nominative Objective Possessive Singular First Person I me my, mine Second Person you you your, yours Third Person he, she, it him, her, it his, her, hers, its Plural First Person we us our, ours Second Person you you your, yours Third Person they them their, theirs The nominative form of a personal pronoun is used when the pronoun functions as a subject, as part of a compound subject, or as a predicate nominative. A pronoun used as a predicate nominative is called a predicate pronoun. It takes the nominative case. SUBJECT She is my mother’s niece. PART OF COMPOUND SUBJECT She and I are cousins. PREDICATE PRONOUN The cousin I most resemble is she. The objective form of a personal pronoun is used when the pronoun functions as a direct object, indirect object, or object of a preposition. Use it also when the pronoun is part of a compound object, or when it’s used with an infinitive. An infinitive is the base form of a verb preceded by the word to —to visit, to jog, to play. DIRECT OBJECT You can see her in these old family portraits. INDIRECT OBJECT My aunt sent me invitations to her wedding. OBJECT OF PREPOSITION A distant cousin has been searching for us. PART OF COMPOUND OBJECT My aunt reserved rooms for them and us. -

Finnish Partitive Case As a Determiner Suffix

Finnish partitive case as a determiner suffix Problem: Finnish partitive case shows up on subject and object nouns, alternating with nominative and accusative respectively, where the interpretation involves indefiniteness or negation (Karlsson 1999). On these grounds some researchers have proposed that partitive is a structural case in Finnish (Vainikka 1993, Kiparsky 2001). A problematic consequence of this is that Finnish is assumed to have a structural case not found in other languages, losing the universal inventory of structural cases. I will propose an alternative, namely that partitive be analysed instead as a member of the Finnish determiner class. Data: There are three contexts in which the Finnish subject is in the partitive (alternating with the nominative in complementary contexts): (i) indefinite divisible non-count nouns (1), (ii) indefinite plural count nouns (2), (iii) where the existence of the argument is completely negated (3). The data are drawn from Karlsson (1999:82-5). (1) Divisible non-count nouns a. Partitive mass noun = indef b. c.f. Nominative mass noun = def Purki-ssa on leipä-ä. Leipä on purki-ssa. tin-INESS is bread-PART Bread is tin-INESS ‘There is some bread in the tin.’ ‘The bread is in the tin.’ (2) Plural count nouns a. Partitive count noun = indef b. c.f. Nominative count noun = def Kadu-lla on auto-j-a. Auto-t ovat kadulla. Street-ADESS is.3SG car-PL-PART Car-PL are.3PL street-ADESS ‘There are cars in the street.’ ‘The cars are in the street.’ (3) Negation a. Partitive, negation of existence b. c.f. -

AN INTRODUCTORY GRAMMAR of OLD ENGLISH Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies

AN INTRODUCTORY GRAMMAR OF OLD ENGLISH MEDievaL AND Renaissance Texts anD STUDies VOLUME 463 MRTS TEXTS FOR TEACHING VOLUme 8 An Introductory Grammar of Old English with an Anthology of Readings by R. D. Fulk Tempe, Arizona 2014 © Copyright 2020 R. D. Fulk This book was originally published in 2014 by the Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies at Arizona State University, Tempe Arizona. When the book went out of print, the press kindly allowed the copyright to revert to the author, so that this corrected reprint could be made freely available as an Open Access book. TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE viii ABBREVIATIONS ix WORKS CITED xi I. GRAMMAR INTRODUCTION (§§1–8) 3 CHAP. I (§§9–24) Phonology and Orthography 8 CHAP. II (§§25–31) Grammatical Gender • Case Functions • Masculine a-Stems • Anglo-Frisian Brightening and Restoration of a 16 CHAP. III (§§32–8) Neuter a-Stems • Uses of Demonstratives • Dual-Case Prepositions • Strong and Weak Verbs • First and Second Person Pronouns 21 CHAP. IV (§§39–45) ō-Stems • Third Person and Reflexive Pronouns • Verbal Rection • Subjunctive Mood 26 CHAP. V (§§46–53) Weak Nouns • Tense and Aspect • Forms of bēon 31 CHAP. VI (§§54–8) Strong and Weak Adjectives • Infinitives 35 CHAP. VII (§§59–66) Numerals • Demonstrative þēs • Breaking • Final Fricatives • Degemination • Impersonal Verbs 40 CHAP. VIII (§§67–72) West Germanic Consonant Gemination and Loss of j • wa-, wō-, ja-, and jō-Stem Nouns • Dipthongization by Initial Palatal Consonants 44 CHAP. IX (§§73–8) Proto-Germanic e before i and j • Front Mutation • hwā • Verb-Second Syntax 48 CHAP. -

Dative Case What Are the Main Contexts in Which the Dative Case Is Used? What Are the Forms of the Dative Case for Nouns in the Singular and Plural?

Dative Case What are the main contexts in which the dative case is used? What are the forms of the dative case for nouns in the singular and plural? One of the most frequent uses of the dative is as the indirect object of a verb. The indirect object is usually a person or animate being that is the recipient in an agent-object-recipient transaction. We can think of a typical “giving” scenario in which someone (an agent or doer of an action) gives an object to someone else (the recipient). The Czech dative is used to mark the recipient of the object. We have indirect objects in all kinds of English sentences, but the most we do to mark them is put a preposition (to or for) in front of them: Jakub gave Honza a puppy (Jakub gave a puppy to Honza), David made tea for his friends, Lidka bought her mother flowers (She bought flowers for her mother), The teacher lent the student a book, Did you send a postcard also to your parents?… Czech datives overlap with many English indirect objects and are used in much the same way. Some examples: Jakub dal Honzovi pejska. nom: Honza gave puppy David uvařil kamarádům čaj. nom pl: kamarádi boiled tea Lidka koupila mamince květiny. nom: maminka bought flowers Učitelka půjčila žákyni knihu. nom: žákyně lent student Poslal jsi pohled i rodičům? nom pl: rodiče did-you-send postcard also parents When you learn a new verb in Czech, ask yourself (or your teacher, if you’re not sure) if it’s a verb that requires the dative case and add that information to your flashcard for that verb. -

Positions for Oblique Case-Marked Arguments in Hungarian Noun Phrases1

17.1-2 (2016): 295-319 UDC 811.511.141'367.4=111 UDC 811.511.411'367.622=111 Original scientific article Received on 10. 07. 2015 Accepted for publication on 12. 04. 2016 Judit Farkas1 Gábor Alberti2 1Hungarian Academy of Sciences 2University of Pécs Positions for oblique case-marked arguments in Hungarian noun phrases1 We argue that there are four positions open to oblique case-marked arguments within the Hungarian noun phrase structure, of which certain ones have never been mentioned in the literature while even the others have been discussed very scarcely (for different reasons, which are also pointed out in the paper). In order to formally account for these four positions and the data “legitimizing” them, we provide a new DP structure integrating the basically morphology-based Hungarian traditions with the cartographic Split-DP Hypothesis (Giusti 1996; Ihsane and Puskás 2001). We point out that, chiefly by means of the four posi- tions for oblique case-marked arguments in Hungarian noun phrases and the operator layers based upon them, this language makes it possible for its speakers to explicitly express every possible scopal order of arguments of verbs, even if the given verbs are deeply embedded in complements of deverbal nominalizers. Key words: Hungarian noun phrase; generative syntax; Split-DP Hypothesis; oblique case-marked arguments; possessive construction. 1 We are grateful to OTKA NK 100804 (Comprehensive Grammar Resources: Hungarian) for their financial support. The present scientific contribution is dedicated to the 650th anniversary of the foundation of the University of Pécs, Hungary. 295 Judit Farkas – Gábor Alberti: Positions for obliques case-marked arguments in Hungarian noun phrases 1. -

The Special Datives

The Special Datives To this point, the functions of the Dative Case have been 1. Indirect Object of give, tell, show verbs 2. Dative with Special Adjectives friendly to, unfriendly to, similar to, dissimilar to, equal to, suitable for, near to, dear to, pleasing to, etc. 3. Dative with Special Intransitive Verbs parco, mando, impero, noceo, resisto, studeo, etc. 4. Dative with Certain Compound Verbs praesum, praeficio, occurro, etc. (often verbs with prefixes of ob- and prae-) Two new Dative Case functions, sometimes called Special Datives, are explained in Unit XIII. These are the Dative of Purpose and the Dative of Reference. 1. Dative of Purpose. Sometimes, the idea of purpose can be stated in a single noun. In such a case, the Dative Case form of the noun is used. It answers the question, “For what purpose does something exist?” Note how we often ask, “What is that for?” The consul donated money for a reward. Consul pecuniam praemio donavit. Seven common Latin nouns are often used as (for?!) the Dative of Purpose: Principal Parts Dative Singular Form Meaning cura, -ae, f. curae for a concern auxilium, -I, n. auxilio for a help impedimentum, -I, n. impedimento for an obstacle praemium, -I, n. praemio for a reward praesidium, -I, n. praesidio for a guard subsidium, -I, n. subsidio for a support usus,, -us, m. usui for a use NOTA BENE: These are not the only nouns which may be used for purpose; they are only the most common. Sometimes a plural Dative Case form is used for purpose. Catullus poeta scripsit puellas esse curis.