312526 Cottle & Cooper Contents P1.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

09/30/2016 Daily Program Listing II 07/27/2016 Page 1 of 119

Daily Program Listing II 43.1 Date: 07/27/2016 09/01/2016 - 09/30/2016 Page 1 of 119 Thu, Sep 01, 2016 Title Start Subtitle Distrib Stereo Cap AS2 Episode 00:00:01 Newsline APTEX (S) (CC) N/A #7109 00:30:00 In Good Shape WNVC (S) (CC) N/A #332 01:00:00 New Tanglewood Tales: Backstage with Rising Artists APTEX (S) (CC) N/A #104H New Tanglewood Tales: Backstage with Rising Artists features members of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, including flutist Elizabeth Rowe; concertmaster Malcolm Lowe; percussionist Dan Bauch, and members of the bass section and trumpet section working with the fellows. Tension is involved in preparing for The Festival of Contemporary Music. The fellows blow off steam at a big dance party. 01:30:00 Music Voyager APTEX (S) (CC) N/A #704H The Exumas The islands of Exuma are the picture perfect description of a Caribbean paradise. Stories, myths and legends fuse with everyday life across the 365 islands within the Exumas. With Mirissa Neff, as guide, one begins to understand that the treasure is scattered in the beauty of the Exumas- from the natural Blue Holes and the fresh conch salad to the roasted grouper and lobster and crabs. She follows the island legends to discover that the land and ocean blend perfectly into the story of the Exumas. 02:00:00 Xerox Rochester International Jazz Festival APTEX (S) (CC) N/A #704H Antonio Sanchez & Migration Four-time Grammy Award winner Antonio Sanchez is considered by many critics and musicians alike as one of the most prominent drummers, bandleaders and composers of his generation. -

P36-37 Layout 1

lifestyle WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 12, 2014 GOSSIP Bradley Cooper is ‘living the dream’ he 39-year-old actor can’t believe the success he is enjoying in his career and feels lucky to work with such respected names as Clint TEastwood - who will direct him in ‘American Sniper’ - and filmmaker David O Russell, who directed him in both ‘Silver Linings Playbook’ and ‘American Hustle’. Responding to a comment he always seems “honored and grateful” for Oscar attention, he said: “It would be hard not to be. I get to do the things I dreamt of as a kid, like working now with Clint Eastwood and being able to work twice with David O Russell. I am absolutely living the dream.” Bradley has received his second Best Actor nomination in a row this year and admits he still doesn’t think he deserves to be consid- ered. Speaking at the annual Academy Awards Nominees Luncheon at the Beverly Hilton hotel in Beverly Hills yesterday he added: “To be able to be a part of this kind of thing two years in a row, I just keep waiting for them to take me away and say, ‘Sorry, sir, what are you doing here?’ Maybe it’s the way I was raised.” Rosie Whiteley he pair - who live together in Los Angeles - have to marry been dating since 2010 and are said to have plans to Ttie the knot near the blonde beauty’s parents home town in south west England. A source told Yahoo Celebrity: “They’re getting married this summer, it’ll be a country Jason Statham wedding where Rosie grew up in Devon, close to her par- ents’ farm. -

Downton Abbey Siebenteilige Serie Im ZDF-Weihnachtsprogramm

Downton Abbey Siebenteilige Serie im ZDF-Weihnachtsprogramm Ab Freitag, 21. Dezember 2012, 20.15 Uhr in ZDFneo Ab Sonntag, 23. Dezember 2012, 17.05 Uhr im ZDF 2 Weltweite Faszination: Superlative und Preise Vorwort von Susanne Müller 4 Auf einen Blick: Die Sendetermine in ZDF und ZDFneo 5 "Downton Abbey": Stabliste, Darsteller, Infos zur Serie 8 Die Inhalte der einzelnen Folgen 21 Who is who in Downton Abbey? Rollenprofile 25 Die Weltsicht von Lady Violet – eine Auswahl von Zitaten 26 Biografien 29 Bildhinweis, Kontakt, Impressum z.presse 12. November 2012 Weltweite Faszination: Superlative und Preise Die erfolgreiche Serie "Downton Abbey" als Free-TV-Premiere im ZDF Ich freue mich sehr, dass ZDF und ZDFneo rund um Weihnachten endlich die deutsche Free-TV-Premiere der weltweit erfolgreichsten britischen Serie seit 30 Jahren zeigen können. Superlative begleiten dieses Programm seit seiner Erstausstrahlung im britischen Sender ITV im Herbst 2010. Zuschauer und Kritiker wa- ren gleichermaßen begeistert. Höchste Zuschauerzahlen und Abruf- zahlen im Internet, ein Eintrag im Guinness-Buch der Rekorde als von den Kritikern am besten bewertete Fernsehserie. Die meisten Nomi- nierungen bei den amerikanischen Primetime-Emmys, die jemals eine ausländische Serie erhielt. Zahlreiche Preise und Auszeichnungen. Weltweit verkauft. Die erfolgreichste DVD-Box eines großen Internet- Kaufhauses. All das zeigt: "Downton Abbey" hat eine große Fange- meinde gewonnen, die sich nach Fortsetzung sehnt. Inzwischen wurde in England schon die dritte Staffel ausgestrahlt und der Erfolg ist un- gebrochen. Doch worin liegt diese Faszination begründet? Ist nicht jeder von uns ein bisschen Voyeur? Der Erfolg der Hochglanzmagazine, die über die Schönen und Reichen und vor allem die Adligen dieser Welt berichten, spricht dafür. -

The Midlands Essential Entertainment Guide

Midlands Cover - Feb_Mids Cover - August 28/01/2013 18:00 Page 1 MIDLANDS WHAT’S MIDLANDS ON WHAT’S THE MIDLANDS ESSENTIAL ENTERTAINMENT GUIDE ISSUE 326 FEBRUARY 2013 www.whatsonlive.co.uk £1.80 ISSUE 326 FEBRUARY 2013 MICKY FLANA TOURS THEG REGIONAN INSIDE Harry Hill back on the circuit THE DEFINITIVE interview inside LISTINGS GUIDE Tara Fitzgerald on making her RSC debut interview inside Sheila Reid Benidorm actress leaves her scooter behind... interview inside PART OF MIDLANDS WHAT’S ON MAGAZINE GROUP PUBLICATIONS GROUP MAGAZINE ON WHAT’S MIDLANDS OF PART What’sOn MAGAZINE GROUP Hot Right Now and appearing in Brum... ISSN 1462-7035 GRAND_FP- Feb13_Layout 1 28/01/2013 14:51 Page 1 Great Theatre at the Grand! MON 4 - SAT 9 FEB TUES 12 - SAT 16 FEB SUN 17 - TUES 19 FEB ‘BRILLIANT! ITEXPLODESLIKEGLITTERINGFIREWORKS’ Russia’s acclaimed ballet company BILL KENWRIGHT BY ARRANGEMENT WITH THE REALLY USEFUL GROUP PRESENTS returns to Wolverhampton following a sensational season in 2012 The Nutcracker Coppélia Swan Lake Performed by LYRICS BY MUSIC BY TIM RICE ANDREW LLOYD WEBBER The Russian State Ballet & Orchestra of Siberia STARRING KEITH JACK WED 20 FEB FRI 22 FEB TUES 26 FEB - SAT 2 MARCH SPOT © Eric Hill / SalSPOT lTd, 2012 licEnSEd by SalSPOT lTd. funwiTHSPOT.cOm WED 6 - SAT 9 MARCH ALSO BOOKING TUES 19 - SAT 30 MARCH SAT 23 FEBRUARY THE BILLY FURY YEARS TUES 12 - SAT 16 MARCH WOLVERHAMPTON MUSICAL COMEDY COMPANY FOOTLOOSE TUESDAY 2 - WEDNESDAY 3 APRIL HORMONAL HOUSEWIVES SAT 6 APRIL JIM DAVIDSON SUNDAY 7 APRIL THE SOLID SILVER 60s SHOW -

Downton Abbey, the Final Season Sundays, Beginning January 3, at 9:00 P.M

PROGRAM GUIDE JANUARY 2016 VOL. 46 NO. 1 Downton Abbey, The Final Season Sundays, beginning January 3, at 9:00 p.m. Join us for the final season of the best-loved drama by Masterpiece on PBS®. Will Carson and Mrs. Hughes make it down the aisle? Will Branson find happiness in America? Will Mary snap up the affections of the "snappy chariot" driver? Let’s make this a season of celebration, as we prepare to say goodbye to the show we've all come to love. Details coming soon about WPSU's Downton Abbey Farewell event on March 6! Sherlock: The Abominable Bride Friday, January 1, at 9:00 p.m. The game is afoot. Benedict Cumberbatch (The Imitation Game) and Martin Freeman (The Hobbit) return as Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson in the acclaimed modern retelling of Arthur Conan Doyle's classic stories. But now, our heroes find themselves in 1890s London in this 90-minute special. The Investment Mercy Street Holding History: Thursday, January 14, Sundays, starting January 17, The Collections of at 8:00 p.m. at 10:00 p.m. Charles L. Blockson Student entrepreneurs from Penn Based on real events, this new series Thursday, January 21, State, Bucknell, and the University from Masterpiece on PBS® is a Civil at 8:30 p.m. of Pittsburgh at Johnstown present War era medical drama, which takes their business ideas to a panel of us beyond the battlefield and into A new WPSU original production, judges, Shark Tank-style. The team the lives of Americans on the home this short form documentary tells the or teams with the strongest ideas front — facing the unprecedented story of Charles L. -

Luther Saturdays at 10 P.M

Trusted. Valued. Essential. FEBRUARY 2016 Luther Saturdays at 10 p.m. beginning February 20 Vegas PBS A Message From the Management Team General Manager General Manager Tom Axtell, Vegas PBS Production Services Manager Kareem Hatcher Communications and Brand Management Director Shauna Lemieux Individual Giving Director Kelly McCarthy Business Manager Brandon Merrill Outdoor Nevada Content Director as Vegas is an improbable city in the harsh Mojave Desert. Many of our Cyndy Robbins new residents are unaware of the desert’s beauty and biological diversi- Workforce Training & Economic Development Director Debra Solt ty, so when it is hot or cold, they often stay home in the air conditioned Corporate Partnerships Director cocoon of their residence. Bruce Spotleson But Nevada is not only a desert; we have snowcapped mountains, Lalpine meadows, limestone caves, extinct fossil beds, ghost towns, lakes, and even gey- Southern Nevada Public Television Board of Directors Executive Director sers. Fortunately we do not have to travel very far to experience them all. Tom Axtell, Vegas PBS Members tell us they donate to Vegas PBS because we present programs that edu- President cate, present the arts, and transport viewers to places they never knew existed.That is Bill Curran, Ballard Spahr, LLP why we are so pleased to bring together program sponsors, recreational experts and Vice President talented producers to present Outdoor Nevada on Wednesday nights at 7:30 pm. It Nancy Brune, Guinn Center for Policy Priorities will join the regular lineup of outstanding science and nature programs detailed on Secretary Barbara Molasky, Barbara Molasky and Associates pages 10 and 11 of this Vegas PBS Source. -

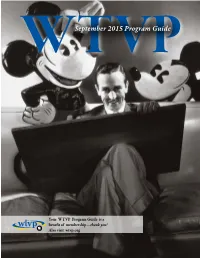

September 2015 Program Guide

WTVPSeptember 2015 Program Guide Your WTVP Program Guide is a benefit of membership—thank you! Also visit wtvp.org 2 2 WTVP—More Choices For more information, please visit Wwtvp. org On the Cover... Walt Disney In 1966, the year Walt Disney died, 240 million people saw a Disney movie, 100 million tuned in to a Disney television program, 80 million bought Disney merchandise, and close to seven million visited Disneyland. Few creative figures before or since have held such a long-lasting place in American life and popular culture. American Experience offers an unprecedented look at the life and legacy of one of America’s most enduring and influential storytellers in Walt Disney, a new two-part, four-hour film premiering Monday and Tuesday, Sep. 14-15 from 8-10 p.m. The film examines Disney’s complex life and enduring legacy, featuring rare archival footage from the Disney vaults, scenes from some of his greatest films, and interviews with biogra- phers, animators and artists who worked on early films, includingSnow White, and the designers who helped turn his dream of Disneyland into reality. Disney’s movies grew out of his own life experiences. He told stories of outsiders struggling for acceptance and belonging, while questioning the conventions of class and authority. As Disney rose to prominence and gained financial security, his work became increasingly celebratory of the American way of life that made his unlikely success possible. Yet despite that success, he was driven and restless, a demanding perfectionist on whom decades of relentless work and chain-smoking would take their toll. -

04/30/2017 Daily Program Listing II 03/19/2017 Page 1 of 117

Daily Program Listing II 43.1 Date: 03/19/2017 04/01/2017 - 04/30/2017 Page 1 of 117 Sat, Apr 01, 2017 Title Start Subtitle Distrib Stereo Cap AS2 Episode 00:00:01 NHK Newsline APTEX (S) (CC) N/A #7261 00:30:00 Global 3000 WNVC (S) (CC) N/A #912H 01:00:00 Song of the Mountains NETA (S) (CC) N/A #1107H Mayberry Deputy, David Browning/Dry Hill Dragger 02:00:00 Woodsongs NETA (S) (CC) N/A #1901H Sweet Honey in the Rock SWEET HONEY IN THE ROCK are Grammy winning folk and civil rights legends who express their history as African-American women through a capella song, dance, and even sign language. While there is no doubt the uniqueness of Sweet Honey is the message, her musical sound is what attracts first-time listeners. Described in the magazine High Fidelity as "breathtaking excursions into harmony singing" and "neck-hair raising" in Downbeat, one is startled at the many musical guises through which the message may appear. WoodSongs is proud to present this Special Event Broadcast from this legacy ensemble as they perform songs from their latest album 'LoveInEvolution'. WoodSongs Kids: Students of Lexington's SCAPA Vocals will be performing the civil rights anthem "We Shall Overcome". 03:00:00 Film School Shorts NETA (S) (CC) N/A #309H It's in the Blood Lambing Season (Columbia University) - Determined to meet the father who left her before she was born, a woman travels to Ireland, hoping it will help her understand his decision. Directed by Jeannie Donohoe. -

Oct 2015 FREE

Slap_October_2015_8_Layout 1 30/09/2015 08:28 Page 1 Issue 52 Oct 2015 FREE Supporting ocal rts & erformers Slap_October_2015_8_Layout 1 30/09/2015 08:28 Page 2 What’s On Gardeners Arms, Droitwich What’s on Entertainment October . Every Weds Quiz Night 8.30pm plus Curry Night £5.00 meal . Tues 6th - 27th Indonesian Day Village Dishes Served 7.30pm £16.00 BOOKING ONLY . Sat 3rd Rickie Laval Ulmate 60's Special Night 7.30pm . Sun 4th Jazz Alchemy Band plus guest singer 1.30pm . Thurs 8th SLAP MAGAZINE Performer of The Month Ben Vickers 8.30pm . Fri 9th Blue Mountain Jordan Live Covers Band Live Music 7.30pm . Tues 13th Tribute to the great Count Basie 2 courses £11.95pp 12.30pm . Fri 16th Everly Bro's Birthday Tribute Singer Live Music 7.30pm 2 Course £12.50pp . Fri 16th - 18th Sun CAMRA Members Jennings Bull's Eye £2.80 pint . Thurs 22nd Your Adverser Night Sponsorship Wilfs Carnival Band Night 8.00pm . Sat 24th Natasha Rock Chic Live The Best of Rock Live Entertainment 8.00pm . Thurs 29th Sally Hosts Droitwich Divas Ladies Night Sing Dance Drink Live Music 8.00p . Fri 30th Mike Skilbeck Live Entertainment 7.30pm . Sat 31st Halloween Fancy Dress Party 8.30pm Book a Party with us - 01905772936 It’s all live @ Gardeners 2 SLAP FEBRUARY Slap_October_2015_8_Layout 1 30/09/2015 08:28 Page 3 It is with more than a little pride that I pen this piece as September draws to a close in fine sunny style. Firstly I am immensely proud to have been part of the wonderful Worcester Music Festival which has been deemed to be a resounding success from all the venues, punters and musicians we have heard from. -

Music Captures the Holiday Season

Music Captures the DECEMBER 2015 Holiday Season Josh Groban was 21 years old when his first public television special,Josh Groban in Concert, debuted on Great Performances in 2002. The program was a prime example of the series’s unique tradition of introducing exciting new musical talents to public television viewers. Groban has appeared on public television many times since, and he returns this month with a new concert spotlighting the Broadway songbook — one of the many special programs we bring you this FINDING NEVERLAND month to celebrate the holiday season. Recorded before a live audience at the historic Los Angeles Theater in downtown L.A., Josh Groban: Stages Live (December 3 at 9:30pm) features the renowned singer performing iconic songs from some of the best-loved Broadway musicals. COURTESY OF TJL; Highlights include “All I Ask of You” (The Phantom of the Opera), a duet with Kelly Clarkson. Broadway musical devotees can also enjoy NYC-ARTS’s behind-the-scenes look at the popular musical Finding Neverland (December 1 at 7:30pm), featuring host Rafael Pi Roman in CLASSICAL REWIND 2, conversation with Tony Award-winning director Diane Paulus and co-stars Matthew Morrison and Laura Michelle Kelly. Dudu Fisher performs hits from Fiddler on the Roof, West Side Story, COURTESY OF TJL; and more in The Voice of Broadway (December 10 at 8pm). WLIW21 is alive with the sound of holiday music with St. Thomas Christmas Jubilant Light 2015 (December 24 at 9pm), which delivers familiar traditional carols and innovative contemporary selections. The popular My Music series returns with two new programs. -

Carol Burnett's Favorite Sketches at 8 Pm Friday, June 3

FRIENDS OF WILL MEMBERSHIP MAGAZINE patterns june 2016 Carol Burnett’s Favorite Sketches at 8 pm Friday, June 3 TM patterns Membership Hotline: 800-898-1065 june 2016 Volume XLIII, Number 12 WILL AM-FM-TV: 217-333-7300 Campbell Hall for Public Telecommunication 300 N. Goodwin Ave., Urbana, IL 61801-2316 Mailing List Exchange Donor records are proprietary and confidential. WILL does not sell, rent or trade its donor lists. Patterns Friends of WILL Membership Magazine Editor: Sarah Whittington Art Director: Michael Thomas Designer: Laura Adams-Wiggs Printed by Premier Print Group. Printed with SOY INK on RECYCLED, TM Trademark American Soybean Assoc. RECYCLABLE paper. Radio 90.9 FM: A mix of classical music and NPR information programs, including local news. (Also heard at 106.5 in Danville and with live Last June, I wrote to you about the anticipation of streaming on will.illinois.edu.) See pages 4-5. budget cuts from the state to both the University 101.1 FM and 90.9 FM HD2: Locally and the Illinois Arts Council. Here we are, a year produced music programs and classical music later, and we’re still reeling from the impact of a from C24. (101.1 is available in the Champaign- state with no budget. As if that weren’t enough, Urbana area.) See page 6. we continue to wonder if a budget for FY 17 will 580 AM: News and information, NPR, BBC, be just as absent. news, agriculture, talk shows. (Also heard on 90.9 FM HD3 with live streaming on will.illinois. And yet, despite the chaos of our state budget, edu.) See page 7. -

ANNUAL REPORT 2013 World Vision UK Trustees’ Report and Accounts for the Year Ended 30 September 2013

ANNUAL REPORT 2013 World Vision UK Trustees’ report and accounts for the year ended 30 September 2013 EVERY CHILD FREE FROM FEAR OUR VISION OUR ACTIVITY Our vision for every child, life in all its fullness; World Vision is the world’s largest international children’s Our prayer for every heart, the will to make it so. charity, working to bring real hope to millions of children in the world’s hardest places. And we do it all as a sign of OUR MISSION God’s unconditional love. To inspire the UK to take action that Poverty, conflict and disaster leave millions of children living transforms the lives of the world’s in fear. Fear of hunger and disease. Fear of violence, conflict poorest children. and exploitation. Fear that robs them of a childhood. OUR GOAL Our local staff work in thousands of communities across the world. They know the names and stories of each child To be transforming the lives of eight million they help to support – children like Jouri and George, children around the world with the help whose stories you can read on pages 3 and 14 of this of 500,000 supporters in the UK. report. They live and work alongside these children, their OUR VALUES families and communities to help change the world they live in for good. The core values that guide our behaviour are: Our worldwide presence means we’re quick to respond to ●●● We are Christian ●●● We are stewards emergencies like conflict and natural disasters. We also use ●●● We are committed ●●● We are partners our influence and global reach to ensure that children are to the poor ●●● We are responsive represented at every level of decision-making.