Do Public Confederate Monuments Constitute Racist Government Speech Violating the Equal Protection Clause?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No

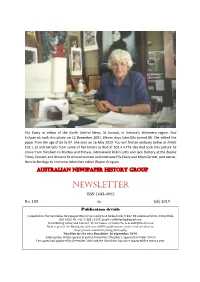

Ella Ebery as editor of the North Central News, St Arnaud, in Victoria’s Wimmera region. Rod Kirkpatrick took this photo on 12 December 2001. Eleven days later Ella turned 86. She edited the paper from the age of 63 to 97. She died on 16 May 2019. You will find an obituary below at ANHG 103.1.13 and extracts from some of her letters to Rod at 103.4.4.The day Rod took this picture he drove from Horsham to Murtoa and Minyip, interviewed Robin Letts and Jack Slattery at the Buloke Times, Donald, and drove to St Arnaud to meet and interview Ella Ebery and Brian Garrett, part owner, then to Bendigo to interview Advertiser editor Wayne Gregson. AUSTRALIAN NEWSPAPER HISTORY GROUP NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No. 103 m July 2019 Publication details Compiled for the Australian Newspaper History Group by Rod Kirkpatrick, U 337, 55 Linkwood Drive, Ferny Hills, Qld, 4055. Ph. +61-7-3351 6175. Email: [email protected] Contributing editor and founder: Victor Isaacs, of Canberra, is at [email protected] Back copies of the Newsletter and some ANHG publications can be viewed online at: http://www.amhd.info/anhg/index.php Deadline for the next Newsletter: 30 September 2019. Subscription details appear at end of Newsletter. [Number 1 appeared October 1999.] Ten issues had appeared by December 2000 and the Newsletter has since appeared five times a year. 1—Current Developments: National & Metropolitan Index to issues 1-100: thanks Thank you to the subscribers who contributed to the appeal for $650 to help fund the index to issues 76 to 100 of the ANHG Newsletter, with the index to be incorporated in a master index covering Nos. -

Orange County Board of Commissioners Agenda Bocc

ORANGE COUNTY BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS AGENDA BOCC Virtual Work Session February 9, 2021 Meeting – 7:00 p.m. Due to current public health concerns, the Board of Commissioners is conducting a Virtual Work Session on February 9, 2021. Members of the Board of Commissioners will be participating in the meeting remotely. As in prior meetings, members of the public will be able to view and listen to the meeting via live streaming video at orangecountync.gov/967/Meeting-Videos and on Orange County Gov-TV on channels 1301 or 97.6 (Spectrum Cable). (7:00 – 7:40) 1. Advisory Board Appointments Discussion (7:40 – 8:20) 2. Additional Discussion Regarding the Regulation of the Discharge of Firearms in Areas of the County with a High Residential Unit Density (8:20 – 9:10) 3. Discussion on Current Policy Regarding Housing Federal Inmates in the Orange County Detention Center (9:10 – 10:00) 4. Discussion on Written Consent for Conducting Vehicle Searches Orange County Board of Commissioners’ meetings and work sessions are available via live streaming video at orangecountync.gov/967/Meeting-Videos and Orange County Gov- TV on channels 1301 or 97.6 (Spectrum Cable). 1 ORANGE COUNTY BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS ACTION AGENDA ITEM ABSTRACT Meeting Date: February 9, 2021 Action Agenda Item No. 1 SUBJECT: Advisory Board Appointments Discussion DEPARTMENT: Board of Commissioners ATTACHMENT(S): INFORMATION CONTACT: Arts Commission - Documentation Clerk’s Office, 919-245-2130 Chapel Hill Orange County Visitors Bureau – Documentation Orange County Board of Adjustment – Documentation Orange County Housing Authority – Documentation Orange County Parks and Recreation Council – Documentation Orange County Planning Board - Documentation PURPOSE: To discuss appointments to the Orange County Advisory Boards. -

Amelia Coleman Thesis

Different, threatening and problematic: Representations of non- mainstream religious schools (Chang, 2016) Amelia Coleman N8306869 Bachelor of Media and Communications (Public Relations) Queensland University of Technology Supervised by Dr Shaun Nykvist (Principal) Dr Rebecca English (Associate) Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Education (Research) Office of Education Research (OER) Faculty of Education Queensland University of Technology 2017 Keywords School choice Media representation Religious schools Multicultural education Marketisation Discourse Identity Pluralism ii Abstract Over recent years we have seen a dramatic increase in representation of Muslim schools within the Australian media. This thesis presents the findings of a study comparing media representations of Muslim schools and “fundamentalist” Christian schools in Australia during a 12-month period in which Muslim schools were receiving significant media attention due to financial mismanagement issues occurring within these schools. During this time period an allegation was made that thousands of dollars of taxpayer funding was being sent to Muslim school’s parent organisation, AFIC, rather than being spent on the education of students (Taylor, 2016). The study focused on comparing how Muslim schools and “fundamentalist” Christian schools were constructed by the media during the timeframe in which Muslim schools were under investigation, and how their media representation may become a proxy for understanding how the Australian public are invited to feel about different types of religious schools. The study draws together Fairclough’s framework for Critical Discourse Analysis with Hall’s work on identity and cultural difference in order to explore inequalities that exist within representations of different varieties of non-mainstream religious schools in Australia. -

Villages Daily Sun Inks Press, Postpress Deals for New Production

www.newsandtech.com www.newsandtech.com September/October 2019 The premier resource for insight, analysis and technology integration in newspaper and hybrid operations and production. Villages Daily Sun inks press, postpress deals for new production facility u BY TARA MCMEEKIN CONTRIBUTING WRITER The Villages (Florida) Daily Sun is on the list of publishers which is nearer to Orlando. But with development trending as winning the good fight when it comes to community news- it is, Sprung said The Daily Sun will soon be at the center of the papering. The paper’s circulation is just over 60,000, and KBA Photo: expanded community. — thanks to rapid growth in the community — that number is steadily climbing. Some 120,000 people already call The Partnerships key Villages home, and approximately 300 new houses are being Choosing vendors to supply various parts of the workflow at built there every month. the new facility has been about forming partnerships, accord- To keep pace with the growth, The Daily Sun purchased a Pictured following the contract ing to Sprung. Cost is obviously a consideration, but success brand-new 100,000-square-foot production facility and new signing for a new KBA press in ultimately depends on relationships, he said — both with the Florida: Jim Sprung, associate printing equipment. The publisher is confident the investment publisher for The Villages Media community The Daily Sun serves and the technology providers will help further entrench The Daily Sun as the definitive news- Group; Winfried Schenker, senior who help to produce the printed product. paper publisher and printer in the region. -

The Will to Find a Better

This Weekend Smith and Phillips FRIDAY Party Cloudy Middle Schools 47/27 SATURDAY honor rolls Party Cloudy 47/29 SUNDAY Clear 49/23 Page 5 carrborocitizen.com DECEMBER 4, 2008 u OL CALLY OWNed AND OPerATed u VOLUme II NO. XXXVIII FREE The will to find a better way BY TAYloR SISK Nicholas Stratas refers to mental His sentiments are echoed by are overcrowded and are losing federal Staff Writer illness as a “fragmenting” problem. mental health advocates throughout funding. The new $138 million facil- Stratas, a Raleigh-based psychia- the state. We’ve suffered, they say, ity in Butner, Central Regional Hospi- trist and former state deputy com- from a lack of leadership and the ab- tal, has just been determined by state BREAKDowN missioner of mental health, explains sence of a cohesive vision of how to inspectors to be unsafe. And mental that as we become adults, individua- deal with those who are stigmatized health care services are all but nonexis- A series tion takes place – boundaries develop, because of their disease. tent in many areas of the state. In sum, thoughts, feelings and actions are They argue for an approach that the measures promised by House Bill on Mental forged – and we go through a process brings to the table the objectives and 381, the reform legislation passed in of internal integration. We begin to concerns of those with mental illness, 2001 that called for moving the men- form relationships. their families and mental health care tally ill out of state institutions and Health Care But with mental illness, instead professionals – voices that have been into community-based services and for of integration there is fragmentation, inadequately heard for at least three de- those services to be offered by private in NC and that restricts our ability to con- cades. -

NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No

Some front pages from Melbourne’s Herald Sun (Australia’s biggest selling daily) during 2016. AUSTRALIAN NEWSPAPER HISTORY GROUP NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No. 91 February 2017 Publication details Compiled for the Australian Newspaper History Group by Rod Kirkpatrick, U 337, 55 Linkwood Drive, Ferny Hills, Qld, 4055. Ph. +61-7-3351 6175. Email: [email protected] Contributing editor and founder: Victor Isaacs, of Canberra, is at [email protected] Back copies of the Newsletter and some ANHG publications can be viewed online at: http://www.amhd.info/anhg/index.php Deadline for the next Newsletter: 30 April 2017. Subscription details appear at end of Newsletter. [Number 1 appeared October 1999.] Ten issues had appeared by December 2000 and the Newsletter has since appeared five times a year. 1—Current Developments: National & Metropolitan 91.1.1 Fairfax sticks to print but not to editors-in-chief Fairfax Media chief executive Greg Hywood has said the company will “continue to print our publications daily for some years yet”. Hywood said this in mid-February in an internal message to staff after appointing a digital expert, Chris Janz, to run its flagship titles, the Sydney Morning Herald, Melbourne’s Age and the Australian Financial Review. Janz, formerly the director of publishing innovation, is now the managing director of Fairfax’s metro publishing unit. Hywood said, “Chris has been overseeing the impressive product and technology development work that will be the centrepiece of Metro’s next-generation publishing model.” Janz had run Fairfax’s joint venture with the Huffington Post and before that founded Allure Media, which runs the local websites of Business Insider, PopSugar and other titles under licence (Australian, 15 February 2017). -

Evidence Based Policy Research Project 20 Case Studies

October 2018 EVIDENCE BASED POLICY RESEARCH PROJECT 20 CASE STUDIES A report commissioned by the Evidence Based Policy Research Project facilitated by the newDemocracy Foundation. Matthew Lesh, Research Fellow This page intentionally left blank EVIDENCE BASED POLICY RESEARCH PROJECT 20 CASE STUDIES Matthew Lesh, Research Fellow About the author Matthew Lesh is a Research Fellow at the Institute of Public Affairs Matthew’s research interests include the power of economic and social freedom, the foundations of western civilisation, university intellectual freedom, and the dignity of work. Matthew has been published on a variety of topics across a range of media outlets, and provided extensive commentary on radio and television. He is also the author of Democracy in a Divided Australia (2018). Matthew holds a Bachelor of Arts (Degree with Honours), from the University of Melbourne, and an MSc in Public Policy and Administration from the London School of Economics. Before joining the IPA, he worked for state and federal parliamentarians and in digital communications, and founded a mobile application Evidence Based Policy Research Project This page intentionally left blank Contents Introduction 3 The challenge of limited knowledge 3 A failure of process 4 Analysis 5 Limitations 7 Findings 8 Federal 9 Abolition and replacement of the 457 Visa 9 Australian Marriage Law Postal Survey 13 Creation of ‘Home Affairs’ department 16 Electoral reform bill 19 Enterprise Tax Plan (Corporate tax cuts) 21 Future Submarine Program 24 Media reform bill 26 -

Media Release

Media Release 24 April, 2014 The Daily Telegraph and NewsLocal launch phase two of their ‘Fair Go for the West’ campaign: ‘Champions of the West’ grants program The Daily Telegraph and NewsLocal have launched ‘Champions of the West’, a grants program that will support local community initiatives in Australia’s third largest economic region, Western Sydney. ‘Champions of the West’ will award twelve $10,000 grants to individuals, groups and businesses that require funding to launch projects that will make a difference in their community. It will then recognise and celebrate the individuals behind the initiatives. A panel of judges, including Brett Clegg, State Director, News NSW; Katie Page, CEO, Harvey Norman; and Professor Barney Glover, Vice-Chancellor, University of Western Sydney, will choose the winners, who will be announced at an event on Tuesday 3 June 2014. ‘Champions of the West’ is a key part of The Daily Telegraph and NewsLocal’s ‘Fair Go for the West’ campaign that aims to improve infrastructure and increase focus on Western Sydney. The Daily Telegraph deputy editor Ben English said: “The Champions of the West program was established to celebrate and reward innovation in this exciting and vibrant section of Sydney. And with the support of our corporate partners, and also CH7 News and Nova 96.9, we are sure to uncover some exciting new projects that will benefit the community for years to come. “We are already overwhelmed by the quality and breadth of Champions that have been nominated for the $10,000 grants. Deciding who gets -

Durham Joins Other NC Cities, Counties in Requiring Masks in All Indoor Settings

Durham, NC, to require everyone to wear masks indoors | Durham Herald Sun 8/9/21, 11(26 AM SECTIONS DURHAM COUNTY Durham joins other NC cities, counties in requiring masks in all indoor settings BY JULIAN SHEN-BERRO UPDATED AUGUST 09, 2021 08:55 AM ! " # $ $ The Delta variant, which is more contagious than other strains, makes up most of North Carolina’s COVID-19 cases. DHHS says vaccinations can protect you from hospitalization and death and help stop how quickly severe cases are risinG in the state. BY NORTH CAROLINA DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES Only have a minute? Listen instead -03:44 Powered by Trinity Audio Durham County and city officials announced a new state of emergency, to begin Monday, that requires everyone to wear masks indoors regardless of vaccination status. Though there are specific exemptions, the mandate applies to everyone age 5 and older. The news comes as North Carolina sees a rising number of COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations and tests returning positive, mostly due to the delta variant spreading among people who have not been vaccinated. TOP ARTICLES https://www.heraldsun.com/news/local/counties/durham-county/article253348598.html Page 1 oF 7 Durham, NC, to require everyone to wear masks indoors | Durham Herald Sun 8/9/21, 11(26 AM Hispanic people more likely to die at home from COVID-19 in North Carolina Several other cities and towns across North Carolina have declared states of emergency and imposed similar requirements. In the town of Boone in Watauga County, a state of emergency that takes effect Tuesday evening requires everyone age 2 and older to wear masks, The Charlotte Observer reported. -

2018 TERMS and CONDITIONS 1. Information on How

2018 TERMS AND CONDITIONS 1. Information on how to participate forms part of the terms and conditions. Your participation as described below is deemed acceptance of these terms and conditions. 2. The Promoter is Nationwide News Pty Ltd (ABN 98 008 438 828) of 2 Holt Street Surry Hills NSW 2010. 3. Participation is open to all Australian residents aged 13 years and over. Participants under the age of 18 must obtain prior permission of their legal parent or guardian over the age of 18 to enter. 4. How to participate in Snap Australia: a. Photos must be taken in Australia between 8 May, 2018 to 30 December, 2018 and be originals. b. Participate through any of the following social media platforms: (i) Twitter: Tweet your photo with #Snap[REGION] publication as per the publication/hashtag list below. It is optional to tag or @mention your News Corp Australia publication. (ii) Instagram: Post your photo with #Snap[REGION] as per the publication/hashtag list below. Ensure your profile is public to ensure visibility. It is optional to tag or @mention your News Corp Australia publication. (iii) Facebook: Post your photo with #Snap[REGION] as per the publication/hashtag list below. Ensure your post is public to ensure visibility. It is optional to tag or @mention your News Corp Australia publication. c. The following News Corp Australia publications are participating using the following hashtags and tags on Instagram (and these need to be referenced as per the below instructions for the different platforms): @thecairnspost Cairns Post #SnapCairns -

2019 Feb EOIR Morning Briefing

EOIR MORNING BRIEFING U.S. Department of Justice Executive Office for Immigration Review By TechMIS Mobile User Copy and Searchable Archives Friday, Feb. 1, 2019 [TX] 1 in 6 migrants granted asylum in Executive Office for Immigration San Antonio immigration courts .............. 8 Review [CA] Hundreds in line at California Hundreds show up for immigration-court immigration court ......................................... 8 hearings that turn out not to exist ........... 2 [CA] Confusion erupts as dozens show Courts turn away hundreds of up for fake court date at SF immigration immigrants, blame shutdown ................... 3 court ................................................................. 9 New wave of 'fake dates' cause chaos Policy and Legislative News in immigration courts Thursday ............... 4 Trump predicts failure by congressional ICE told hundreds of immigrants to committee charged with resolving show up to court Thursday — for many, border stalemate .......................................... 9 those hearings are fake ............................. 5 Family Feud: Dems' border security Immigrants drove hours for fake, ICE- plan takes fire from the left ..................... 10 issued court dates on Thursday ............. 5 Ocasio-Cortez, progressives press DHS Caused Hundreds of Immigrants Pelosi to not increase DHS funding in to Show Up Thursday for Fake Court any spending deal ..................................... 11 Dates ............................................................... 6 Trump, Dem talk of 'smart wall' -

'It Was Just Raining Touchdowns'

Serving UNC students and the University community since 1893 Volume 123, Issue 110 dailytarheel.com Monday, November 9, 2015 Title IX programs increase costs UNC-system schools are working to comply with new regulations. By Danielle Chemtob Staff Writer A wave of gender discrimina- tion regulations in the last year has forced UNC-system schools to rapidly rework their policies and expand staff — a cost schools have incurred without assistance. Many of these regulations stem from the Campus Security Initiative, a systemwide report released by the UNC General Assembly in July 2014. To comply with the report’s recom- mendations that went into effect beginning fall 2014, many UNC campuses have turned to hiring full-time Title IX coordinators with established qualifications — DTH/KATIE WILLIAMS though a full-time coordinator is Redshirt senior Marquise Williams now holds North Carolina’s record for career touchdowns, with 83, after his five touchdowns against Duke on Saturday. not technically recommended. Title IX, which was signed into law in 1972, prevents gen- der discrimination in federally funded schools nationwide. ‘It was just raining touchdowns’ Recommendations have meant a financial impact on UNC-system schools as they aim to hire additional staff mem- Marquise Williams set multiple school records on Saturday bers, said Dawn Floyd, a UNC- Charlotte Title IX coordinator FOOTBALL He snapped.” senior guard Landon Turner, who game. The 66 points the Tar Heels who began her role in 2014. The snap happened on UNC’s was part of an offensive line that pre- put up were the most any previous “All of these regulations and NORTH CAROLINA 66 first offensive play of the game, vented the then-No.