THE MANUSCRIPTS 2.1 General Observations the 21 Manuscripts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Preliminary Survey

THE PRONUNCIATION TRADITION OF BIBLICAL HEBREIV AMONG THE JEWS OF COCHIN: A PRELIMINARY SURVEY Jarmo Forsström r. INTRODUCTION The small colony of Jews in Cochin in south-western lndia has attracted the attention of travellers and scholars since the beginning of Portuguese rule in that areâ (1502-1663), when the existence of a Jewish settlement there became known in the West. Almost all facets of the life of this community have been studied and published in numerous articles and books, except for their traditional pronunciation of Hebrew. This gap in our otherwise deøiled knowledge of the Cochin Jews needs urgently to be filled, because this com- munity wittr its unique features is rapidly disappearing in India and becoming assimilated in Israel too. The anival of Jews on the Malabar coast in South-west India has remained shrouded in mystery, in spite of the ca¡eful research that has been undertaken in an aüempt to discover their origin. The study of the origin of the Cochin Jews and of the time of their a¡rival in India is greatly hampered by the fact that their history before the end of the first millennium cE is totally hidden behind folklore, legends and folk songs. Much has been done by the Cochinites themselves and by scholars around the world to strain historical clues from this heterogeneous material, nevertheless without producing many results. The following summary of the history of the Cochin Jews accords more or less with those who have dealt with the subject.l The Cochin Jews have preserved various old legends conceming the coming of their ancestors to the Malabar coast. -

(Cf. 1.Common Semitic) a Bibliography of Ugaritic

6A. STANDARD HEBREW 6A.1. BIBLIOGRAPHY (cf. 1. Common Semitic ) A Bibliography of Ugaritic Grammar and Biblical Hebrew in the Twentieth Century , by M. Smith [http://oi.uchicago.edu/OI/DEPT/RA/bibs/BH-Ugaritic.html: pdf, doc, rtf]. “A classified discourse analysis bibliography”, by K.E. Lowery, in DABL , pp. 213-253. An Index of English Periodical Literature on the Old Testament and Ancient Near Eastern Studies , 2 vols. (American Theological Library Association. Bibliography Series 21), by W.G. Hupper, Philadelphia 1987-1999. ´ “Bibliografia historii i kultury Zydów w Polsce za rok 1994”, by St. G ąsiorowski, Studia Judaica Crocoviensia: Series Bibliographica 2 (10), Krakow 2002 [Bibliography on the history and culture od the Jews in Poland for the year 1994]. “Bibliographie, Altes Testament/Qumran”, AfO 14, 1941-1944 // 29-30, 1983-1984 (Palestina und Syrien ; Altes Testament un nachbiblische Schriftum ; Die handschriftenfunde am Toten Meer/Qumran). Bibliographie biblique/Biblical Bibliography/Biblische Bibliographie/Bibliografla biblica/Bibliografía bíblica. III : 1930-1983 , by P.-E. Langevin, Québec 1985 [‘Philologie’, 335-464]. “Bibliographische Dokurnentation: lexikalisches und grammatisches Material”, bearb. von T. Ijoherty et al. , ZAH l, 1988, 122-137, 210-234. “Bibliographische Dokumentation: lexikalisches und grammatisches Material”, bearb. von W. Breder et al. , ZAH 2, 1989, 93-119; 2, 1989, 213-243, 3, 1990, 98-125; 3, 1990, 221-231. “Bibliographische Dokumentation: lexikalisches und grammatisches Material”, bearb. von B. Brauer et al. ., ZAH 4, 1991, 95-114,194-209; 5, 1992, 91-112, 226-236; 6, 1993, 128-148; 6, 1993, 243-256 ; 6, 1993, 128-148; 6, 1993, 243-256 ; 7, 1994, 88-100; 7, 1994, 245-257; “Bibliographische Dokumientation: lexikalisches und grammatisches Material”, in Verbindung mit B. -

Israel Prize

Year Winner Discipline 1953 Gedaliah Alon Jewish studies 1953 Haim Hazaz literature 1953 Ya'akov Cohen literature 1953 Dina Feitelson-Schur education 1953 Mark Dvorzhetski social science 1953 Lipman Heilprin medical science 1953 Zeev Ben-Zvi sculpture 1953 Shimshon Amitsur exact sciences 1953 Jacob Levitzki exact sciences 1954 Moshe Zvi Segal Jewish studies 1954 Schmuel Hugo Bergmann humanities 1954 David Shimoni literature 1954 Shmuel Yosef Agnon literature 1954 Arthur Biram education 1954 Gad Tedeschi jurisprudence 1954 Franz Ollendorff exact sciences 1954 Michael Zohary life sciences 1954 Shimon Fritz Bodenheimer agriculture 1955 Ödön Pártos music 1955 Ephraim Urbach Jewish studies 1955 Isaac Heinemann Jewish studies 1955 Zalman Shneur literature 1955 Yitzhak Lamdan literature 1955 Michael Fekete exact sciences 1955 Israel Reichart life sciences 1955 Yaakov Ben-Tor life sciences 1955 Akiva Vroman life sciences 1955 Benjamin Shapira medical science 1955 Sara Hestrin-Lerner medical science 1955 Netanel Hochberg agriculture 1956 Zahara Schatz painting and sculpture 1956 Naftali Herz Tur-Sinai Jewish studies 1956 Yigael Yadin Jewish studies 1956 Yehezkel Abramsky Rabbinical literature 1956 Gershon Shufman literature 1956 Miriam Yalan-Shteklis children's literature 1956 Nechama Leibowitz education 1956 Yaakov Talmon social sciences 1956 Avraham HaLevi Frankel exact sciences 1956 Manfred Aschner life sciences 1956 Haim Ernst Wertheimer medicine 1957 Hanna Rovina theatre 1957 Haim Shirman Jewish studies 1957 Yohanan Levi humanities 1957 Yaakov -

Dictionaries

LIST OF PUBLICATIONS THE ACADEMY OF THE HEBREW LANGUAGE ! Prices quoted in U.S. dollars ! The cost of surface postage is included To order publications of the Academy of the Hebrew Language, contact Etti Mishli by e-mail at [email protected] or by phone at +972-2-6493512 PERIODICALS Leshonenu A Journal for the Study of the Hebrew Language and Cognate Subjects Single Issue 15$ Double Issue 25$ Annual Subscription 42$ Ha’Ivrit A Popular Journal for the Hebrew Language Single Issue 7$ Double Issue 15$ Annual Subscription 32$ Zikhronot HaAZqademya Lalashon Ha’Ivrit (Proceedings of the Academy of the Hebrew Language), Vols. 19–57 Single Issue 12$ Aqaddem free GRAMMATICAL PUBLICATIONS The Academic Secretariat | Academy Rulings: Grammar 2014 | 137 pp. | Booklet 22$ The Academic Secretariat | Transcription Rules 22$ 2012 | Ha’ivtrit | vol. 60 , no. 1–2 , 94 pp. The Academic Secretariat | Punctuation Rules; Spelling Rules for Unpointed 10$ Hebrew 2002 | 61 pp. | Booklet BOOKS Shimon Sharvit | A Phonology of Mishnaic Hebrew (Analyzed Materials) 2016 | 478 pp. | Hardcover 47$ Yael Reshef | Hebrew in the Mandate Period 37$ 2015 | 392 pp. | Hardcover Uri Mor | Judean Hebrew: The Language of the Hebrew Documents from 37$ Judea Between the First and the Second Revolts 2015 | 444 pp. | Hardcover Mordechay Mishor | The Consolidation of Early Vocabulary: A Fieldwork 2015 | 120 pp. | Hardcover 25$ Michael Rand and Jonathan Vardi | The Diwan of Samuel Ha-Nagid – A Gniza Codex 2015 | 230 pp. | Hardcover 50$ Moshe Bar-Asher | A Morphology of Mishnaic Hebrew: Introductions and For purchase: Noun Morphology Mosad Bialik, Jerusalem 2015 | 2 vols., 1744 pp. -

9789004263406 12-Buth HLI

The Language Environment of First Century Judaea Jerusalem Studies in the Synoptic Gospels Volume Two Edited by Randall Buth and R. Steven Notley LEIDEN | BOSTON This is a digital offfprint for restricted use only | © 2014 Koninklijke Brill NV Contents Introduction: Language Issues Are Important for Gospel Studies 1 Randall Buth Sociolinguistic Issues in a Trilingual Framework 7 1 The Origins of the “Exclusive Aramaic Model” in the Nineteenth Century: Methodological Fallacies and Subtle Motives 9 Guido Baltes 2 The Use of Hebrew and Aramaic in Epigraphic Sources of the New Testament Era 35 Guido Baltes 3 Hebraisti in Ancient Texts: Does Ἑβραϊστί Ever Mean “Aramaic”? 66 Randall Buth and Chad Pierce 4 The Linguistic Ethos of the Galilee in the First Century C.E. 110 Marc Turnage 5 Hebrew versus Aramaic as Jesus’ Language: Notes on Early Opinions by Syriac Authors 182 Serge Ruzer Literary Issues in a Trilingual Framework 207 6 Hebrew, Aramaic, and the Difffering Phenomena of Targum and Translation in the Second Temple Period and Post-Second Temple Period 209 Daniel A. Machiela 7 Distinguishing Hebrew from Aramaic in Semitized Greek Texts, with an Application for the Gospels and Pseudepigrapha 247 Randall Buth This is a digital offfprint for restricted use only | © 2014 Koninklijke Brill NV vi contents 8 Non-Septuagintal Hebraisms in the Third Gospel: An Inconvenient Truth 320 R. Steven Notley Reading Gospel Texts in a Trilingual Framework 347 9 Hebrew-Only Exegesis: A Philological Approach to Jesus’ Use of the Hebrew Bible 349 R. Steven Notley and Jefffrey P. Garcia 10 Jesus’ Petros–petra Wordplay (Matthew 16:18): Is It Greek, Aramaic, or Hebrew? 375 David N. -

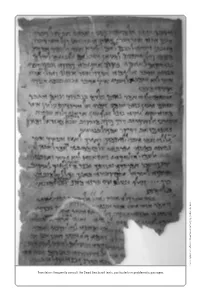

Translators Frequently Consult the Dead Sea Scroll Texts, Particularly in Problematic Passages

Translators frequently consult the Dead Sea Scroll texts, particularly consulttheDeadSeaScroll passages. frequently inproblematic Translators Photo by Berthold Werner. Dead Sea Scroll 4Q175, Jordan, Amman. Why Bible Translations Differ: A Guide for the Perplexed ben spackman Ben Spackman ([email protected]) received an MA in Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations from the University of Chicago, where he pursued further graduate work. Currently a premedical student at City College of New York, he will apply to medical schools in 2014. righam Young once said that “if [the Bible] be translated incorrectly, and Bthere is a scholar on the earth who professes to be a Christian, and he can translate it any better than King James’s translators did it, he is under obli- gation to do so.”1 Many translations have appeared since 1611, and modern Apostles have profitably consulted these other Bible translations, sometimes citing them in general conference or the Ensign.2 Latter-day Saints who likewise wish to engage in personal study from other Bible translations will quickly notice differences of various kinds, not only in style but also in sub- stance. Some differences between translations are subtle, others glaringly obvious, such as the first translation of Psalm 23 into Tlingit: “The Lord is my Goatherder, I don’t want him; he hauls me up the mountain; he drags me down to the beach.”3 While the typical Latter-day Saint reads the Bible fairly often,4 many are unfamiliar with “where the [biblical] texts originated, how they were trans- mitted, what sorts of issues translators struggled with, or even how different types of translations work, or even where to start finding answers.”5 Generally speaking, differences arise from four aspects of the translation process, three 31 32 Religious Educator · VOL. -

The Vocalization of Verbs Containing Gutturals in Tiberian and Babylonian Traditions. an Attempt of Systematic Description

Uniwersytet Warszawski Wydział Orientalistyczny Wiktor Gębski Nr albumu: 305018 The Vocalization of Verbs Containing Gutturals in Tiberian and Babylonian Traditions. An Attempt of Systematic Description Praca magisterska na kierunku orientalistyka w zakresie hebraistyki Praca wykonana pod kierunkiem Dr Angeliki Adamczyk Dr Lidii Napiórkowskiej Zakład Hebraistyki Warszawa, maj 2018 Oświadczenie kierującego pracą Oświadczam, że niniejsza praca została przygotowana pod moim kierunkiem i stwierdzam, że spełnia ona warunki do przedstawienia jej w postępowaniu o nadanie tytułu zawodowego. Data Podpis kierującego pracą Oświadczenie autora (autorów) pracy Świadom odpowiedzialności prawnej oświadczam, że niniejsza praca dyplomowa została napisana przez mnie samodzielnie i nie zawiera treści uzyskanych w sposób niezgodny z obowiązującymi przepisami. Oświadczam również, że przedstawiona praca nie była wcześniej przedmiotem procedur związanych z uzyskaniem tytułu zawodowego w wyższej uczelni. Oświadczam ponadto, że niniejsza wersja pracy jest identyczna z załączoną wersją elektroniczną. Data Podpis autora (autorów) pracy Streszczenie The subject of the present research is the inconsistencies within the vocalization of the Tiberian and Babylonian tradition. The thesis consists of three chapters. While in the first one the general overview of the pronunciation traditions of Biblical Hebrew was given, the second one constitutes a description of the vowel systems of the selected traditions. The third chapter contains the analytical part of the thesis. The collected material included 127 verbal forms from various stems which subsequently were analysed in order to spot fluctuations demonstrated by their vowel systems and prosodic structure. As will be seen, in the Tiberian tradition most of the inconsistencies are a matter of shewa placement and vowel length. Contrary to this, in the Babylonian one the fluctuations occur mostly in the vowel quality. -

The Hebrew Language Council from 1904 to 1914*

Bulletin of the SOAS, 73, 1 (2010), 45–64. © School of Oriental and African Studies, 2010. doi:10.1017/S0041977X09990346 Revisiting the language factor in Zionism: The Hebrew Language Council from 1904 to 1914* İlker Aytürk Bilkent University, Turkey [email protected] Abstract The role of language and linguistic-philological studies in the nationalist movements of the nineteenth century received much attention. The aim of this article is to focus on the language factor in Zionism and the revival of Hebrew as a spoken language in the Yishuv between 1904 and 1914. Founded in 1904, the Hebrew Language Council was expected to enhance the process of revival and, from the very beginning, an unmistakably nationalist attitude to its subject matter marked the Council’s agenda. However, the authority of the Council to make binding decisions on lin- guistic matters was contested by a number of other Zionist institutions, a development which ruined the prestige and effectiveness of the Council. The controversy resulted less from a turf war or quarrels over scarce resources than a deeper question of which institution represented the “true” Hebraic spirit. The World Zionist Organization’s decision to de- align from cultural matters, including the revival of Hebrew, worsened the conditions under which the Council operated. From a comparative per- spective, thus, the Hebrew case provides an unusual case of linguistic nationalism, which should be of interest to students of both nationalism and sociolinguistics. The majority of the scholars in the field of nationalism studies today agree on the modernity of nations and believe nations to be “constructs”, “artefacts” or “ima- gined communities”, invented by a host of nationalist ideologues since the late eighteenth century. -

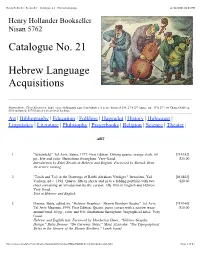

Hebrew Language 11/14/2005 04:01 PM

Henry Hollander, Bookseller - Catalogue 21 - Hebrew Language 11/14/2005 04:01 PM Henry Hollander Bookseller Nisan 5762 Catalogue No. 21 Hebrew Language Acquisitions Shown above, Three Klezmorim, hand-colored lithograph signed and numbered in an edition of 150, 23"x 29" (image size 19"x 25"), by Chaim Goldberg. $300 unframed; $375 framed with archival backing. Art | Bibliography | Education | Folklore | Haggadot | History | Holocaust | Linguistics | Literature | Philosophy | Prayerbooks | Religion | Science | Theater | ART 1. "Scheinfeld." Tel Aviv, Sabra, 1977. First Edition. Oblong quarto, orange cloth, 68 [#14152] pp., b/w and color illustrations throughout. Very Good. $25.00 Introduction by Ethel Broido in Hebrew and English. Foreword by Baruch Oren. An artist's catalog. 2. "Torah and Toil in the Drawings of Rabbi Abraham Verdiger." Jerusalem, Yad [#14802] Vashem, nd c. 1992. Quarto, fifteen sheets laid in to a folding portfolio with two $20.00 sheet containing an introduction by the curator, Elly Dlin in English and Hebrew. Very Good. Text in Hebrew and English. 3. Donner, Batia, edited by. "Hebrew Graphics - Shamir Brothers Studio." Tel Aviv, [#14140] Tel Aviv Museum, 1999. First Edition. Quarto, paper covers with a narrow wrap- $25.00 around band, 80 pp., color and b/w illustrations throughout, biographical notes. Very Good. Hebrew and English text. Foreword by Mordechai Omer.. "Hebrew Graphic Design," Batia Donner. "On Currency Notes," Maoz Azaryahu. "The Typographical Styles in the Oeuvre of the Shamir Brothers," Yanek Iontef. file:///Users/metafo/Polis/Clients/Henry%20Hollander/HOLLANDERCATS/Cat%2021/cat21.htm Page 1 of 63 Henry Hollander, Bookseller - Catalogue 21 - Hebrew Language 11/14/2005 04:01 PM 4. -

Name: Michal Ornan-Ephratt

Prof. Michal ORNAN-EPHRATT Name: Michal Ornan-Ephratt CURRICULUM VITAE 1. Personal Details Permanent Home Address: Nofit 3600100, Israel Home Telephone Number: 04-9930784 Office Telephone Number: 04-8240190 Cellular Phone: ------------ Email Address: [email protected] 2. Higher Education a. Undergraduate and Graduate Studies Period of Name of Institution Degree Degree Study and Department granted Bachelor's degree in linguistics and Bachelors 1976-1979 education, Hebrew University, "Magna Cum 1979 Jerusalem Laude" "Direct Doctoral program", in the Ph.D "Summa 1980-1084 Department of Hebrew Language. Cum Laude". 1984 Majoring in Computational Linguistics, at the Hebrew University, Jerusalem "Direct Doctoral program", at the "Post graduate Linguistic Department and at the worker" 1982 ------ School of Epistemics, Edinburgh University, Scotland b. Post-Doctoral Studies Period of Name of Institution and Department/Lab Study Computational Linguistics, Dept. of Computer Science, University of 1987 Rochester, NY (USA) 1 Prof. Michal ORNAN-EPHRATT 3. Academic Ranks and Tenure in Institutes of Higher Education Years Name of Institution and Department Rank/Position 1982 Dept. of Linguistics, Edinburgh Post graduate worker University, Scotland 1983 Dept. of Hebrew Language, at the Assistant Hebrew University, Jerusalem 1984-5 Dept. of Hebrew Language and Dept. Assistant of Computer science , at the Hebrew University, Jerusalem 1986 IBM Scientific Center, Haifa Research Fellow 1987 Dept. of Computer Science, University Assistant and Research of Rochester, NY (USA) Fellow 1989-1991 Dept. of Hebrew Language, University Lecturer, Proposed rank of Haifa 1991-1996 Dept. of Hebrew Language, University Lecturer of Haifa 1996-2004 Dept. of Hebrew Language, University Senior lecturer + tenure of Haifa 2005-2016 Dept. -

Notes Bibliogràfiques

© IEC, Societat Catalana d’Estudis Hebraics Tamid (Barcelona), 4 (2002-2003) Notes bibliogràfiques I. Bibliografia sobre l’ús i l’estudi de l’hebreu a l’edat mitjana Tot i que l’hebreu no ha tingut mai cap veritable discontinuïtat, en tant que llengua escrita, al llarg del lent i mil·lenari procés que l’ha dut de l’època bíblica fins a la seva represa com a llengua parlada en els temps moderns, hom acostu- ma a denominar amb l’expressió d’hebreu bíblic la fase més antiga, d’hebreu mis- naic o rabínic la llengua postbíblica en què fou redactada la Misnà (viva encara en els primers segles de la nostra era), d’hebreu medieval la que utilitzaren els sa- vis jueus a l’edat mitjana i d’hebreu modern la llengua dels nostres dies. Tanma- teix, per més que l’edat mitjana hagi estat una etapa important del llarguíssim camí que aquesta evolució ha seguit, la denominació d’hebreu medieval aplicada a la llengua d’aquest període no sembla pas del tot pertinent ni és, en realitat, acceptada per tothom, llevat que es prengui en un sentit purament cronològic. Cal entendre que és medieval perquè la referim als erudits i literats jueus de l’e- dat mitjana, però no pas perquè es tracti de cap sistema lingüístic consolidat, amb característiques morfològiques i sintàctiques pròpies, comparable a l’ano- menat hebreu bíblic o a l’hebreu misnaic. L’hebreu medieval és, de fet, el resultat de l’ús que de l’hebreu misnaic van fer els diferents autors en múltiples països i zones culturals musulmanes i cristianes en aquella edat històrica, condicionats per l’entorn sociològic, polític i lingüístic en què vivien. -

Studies in Rabbinic Hebrew

Cambridge Semitic Languages and Cultures Heijmans Studies in Rabbinic Hebrew Studies in Rabbinic Hebrew Shai Heijmans (ed.) EDITED BY SHAI HEIJMANS This volume presents a collec� on of ar� cles centring on the language of the Mishnah and the Talmud — the most important Jewish texts (a� er the Bible), which were compiled in Pales� ne and Babylonia in the la� er centuries of Late An� quity. Despite the fact that Rabbinic Hebrew has been the subject of growing academic interest across the past Studies in Rabbinic Hebrew century, very li� le scholarship has been wri� en on it in English. Studies in Rabbinic Hebrew addresses this lacuna, with eight lucid but technically rigorous ar� cles wri� en in English by a range of experienced scholars, focusing on various aspects of Rabbinic Hebrew: its phonology, morphology, syntax, pragma� cs and lexicon. This volume is essen� al reading for students and scholars of Rabbinic studies alike, and appears in a new series, Studies in Semi� c Languages and Cultures, in collabora� on with the Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Cambridge. As with all Open Book publica� ons, this en� re book is available to read for free on the publisher’s website. Printed and digital edi� ons, together with supplementary digital material, can also be found here: www.openbookpublishers.com Cover image: A fragment from the Cairo Genizah, containing Mishnah Shabbat 9:7-11:2 with Babylonian vocalisat on (Cambridge University Library, T-S E1.47). Courtesy of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library. Cover design: Luca Baff a ebook 2 ebook and OA edi� ons also available OPEN ACCESS OBP To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: htps://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/952 Open Book Publishers is a non-proft independent initiative.