Contents/Sommaire

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oix-Progint Mise En Page 1 10/06/11 11:54 Page1

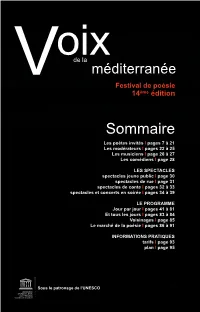

10050077-Voix-progINT_Mise en page 1 10/06/11 11:54 Page1 oixde la V méditerranée Festival de poésie 14ème édition Sommaire Les poètes invités I pages 7 à 21 Les modérateurs I pages 22 à 25 Les musiciens I page 26 à 27 Les comédiens I page 28 LES SPECTACLES spectacles jeune public I page 30 spectacles de rue I page 31 spectacles de conte I pages 32 à 33 spectacles et concerts en soirée I pages 34 à 39 LE PROGRAMME Jour par jour I pages 41 à 81 Et tous les jours I pages 83 à 84 Voisinages I page 85 Le marché de la poésie I pages 86 à 91 INFORMATIONS PRATIQUES tarifs I page 93 plan I page 95 10050077-Voix-progINT_Mise en page 1 10/06/11 11:54 Page2 2 10050077-Voix-progINT_Mise en page 1 10/06/11 11:54 Page3 / édito Festival de poésie e 14 ous le patronage de l’UNESCO, le festival Voix de la Méditerranée va accueillir du 16 au 23 juillet, plus d’une centaine de poètes et Sd’artistes, conteurs, chanteurs et musiciens venus de toute la Méditerranée. A nouveau Lodève vivra du matin au soir au rythme de la poésie avec plus de 200 rendez-vous proposés à un public fidèle et curieux, conquis par l’atmosphère intime de la ville et la convivialité de la manifestation. Depuis 14 ans, l’invitation est lancée aux poètes, aux habitants du Voix de la Méditerranée / Voix territoire et à tous les festivaliers pour partager un temps d’échanges et de dialogue entre les cultures mais aussi entre les générations. -

DIRECTORATE GENERAL for RESEARCH Directorate a Division for International and Constitutional Affairs ------WIP 2002/02/0054-0055 AL/Bo Luxembourg, 13 February 2002*

DIRECTORATE GENERAL FOR RESEARCH Directorate A Division for International and Constitutional affairs ------------------------------------------------------------------- WIP 2002/02/0054-0055 AL/bo Luxembourg, 13 February 2002* NOTE ON THE POLITICAL AND ECONOMIC SITUATION IN ROMANIA AND ITS RELATIONS WITH THE EUROPEAN UNION IN THE FRAMEWORK OF ENLARGEMENT This note has been prepared for the information of Members of the European Parliament. The opinions expressed in this document are the author's and do not necessarily reflect the position of the European Parliament. * Updated 11 March 2002 Sources: - European Commission - European Parliament - European Council - Economic Intelligence Unit - Oxford Analytica - ISI Emerging Markets - Reuters Business Briefing -World Markets Country Analysis - BBC Monitoring Service WIP/2002/02/0054-55/rev. FdR 464703 PE 313.139 NOTE ON THE POLITICAL AND ECONOMIC SITUATION IN ROMANIA AND ITS RELATIONS WITH THE EUROPEAN UNION IN THE FRAMEWORK OF ENLARGEMENT CONTENTS SUMMARY................................................................................................................................ 3 I. POLITICAL SITUATION a) Historical background......................................................................................................3 b) Institutions...................................................................... .................................................5 c) Recent developments...................................................... .................................................6 -

Communism and Post-Communism in Romania : Challenges to Democratic Transition

TITLE : COMMUNISM AND POST-COMMUNISM IN ROMANIA : CHALLENGES TO DEMOCRATIC TRANSITION AUTHOR : VLADIMIR TISMANEANU, University of Marylan d THE NATIONAL COUNCIL FO R EURASIAN AND EAST EUROPEAN RESEARC H TITLE VIII PROGRA M 1755 Massachusetts Avenue, N .W . Washington, D .C . 20036 LEGAL NOTICE The Government of the District of Columbia has certified an amendment of th e Articles of Incorporation of the National Council for Soviet and East European Research changing the name of the Corporation to THE NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR EURASIAN AND EAST EUROPEAN RESEARCH, effective on June 9, 1997. Grants, contracts and all other legal engagements of and with the Corporation made unde r its former name are unaffected and remain in force unless/until modified in writin g by the parties thereto . PROJECT INFORMATION : 1 CONTRACTOR : University of Marylan d PR1NCIPAL 1NVEST1GATOR : Vladimir Tismanean u COUNCIL CONTRACT NUMBER : 81 1-2 3 DATE : March 26, 1998 COPYRIGHT INFORMATIO N Individual researchers retain the copyright on their work products derived from research funded by contract with the National Council for Eurasian and East European Research . However, the Council and the United States Government have the right to duplicate an d disseminate, in written and electronic form, this Report submitted to the Council under thi s Contract, as follows : Such dissemination may be made by the Council solely (a) for its ow n internal use, and (b) to the United States Government (1) for its own internal use ; (2) for further dissemination to domestic, international and foreign governments, entities an d individuals to serve official United States Government purposes ; and (3) for dissemination i n accordance with the Freedom of Information Act or other law or policy of the United State s Government granting the public rights of access to documents held by the United State s Government. -

Religion and Politics in Post-Communist Romania RELIGION and GLOBAL POLITICS SERIES

Religion and Politics in Post-Communist Romania RELIGION AND GLOBAL POLITICS SERIES Series Editor John L. Esposito University Professor and Director Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal Center for Muslim-Christian Understanding Georgetown University Islamic Leviathan Islam and the Making of State Power Seyyed Vali Reza Nasr Rachid Ghannouchi A Democrat within Islamism Azzam S. Tamimi Balkan Idols Religion and Nationalism in Yugoslav States Vjekoslav Perica Islamic Political Identity in Turkey M. Hakan Yavuz Religion and Politics in Post-Communist Romania lavinia stan lucian turcescu 1 2007 3 Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that further Oxford University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education. Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Copyright # 2007 by Oxford University Press, Inc. Published by Oxford University Press, Inc. 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016 www.oup.com Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Stan, Lavinia. Religion and politics in post-communist Romania / Lavinia Stan, Lucian Turcescu. p. cm.—(Religion and global politics series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-19-530853-2 1. -

Absurdistan Refacut Cu Headere Ultimul.P65

Dorin Tudoran (n. 30 iunie 1945, Timi[oara). Absolvent al Facult\]ii de Limb\ [i Literatur\ Român\ a Universit\]ii din Bucure[ti, pro- mo]ia 1968. Este Senior Director, pentru Comunicare [i Cercetare, membru al conducerii executive a Funda]iei Interna]ionale IFES, Washington D.C., Statele Unite, [i redactor-[ef al revistei democracy at large. C\r]i de poezie: Mic tratat de glorie (1973), C`ntec de trecut Akheronul (1975), O zi `n natur\ (1977), Uneori, plutirea (1977), Respira]ie artificial\ (1978), Pasaj de pietoni (1978), Semne particulare (antologie, 1979), De bun\ voie, autobiografia mea (1986), Ultimul turnir (antologie, 1992), Optional Future (1988), Viitorul Facultativ/Optional Future (1999), T`n\rul Ulise (antologie, 2000). C\r]i de publicistic\: Martori oculari (`n colaborare cu Eugen Seceleanu, 1976), Biografia debuturilor (1978), Nostalgii intacte (1982), Adaptarea la realitate (1982), Frost or Fear? On the Condition of the Romanian Intelectual (traducere [i prefa]\ de Vladimir Tism\neanu, 1988), Onoarea de a `n]elege (antologie, 1998), Kakistokra]ia (1998). Pentru unele dintre c\r]ile sale, autorul a primit Premiul Uniunii Scriitorilor (1973, 1977, 1998), Marele Premiu al Asocia]iilor Scriitorilor Profesioni[ti ASPRO (1998), Premiul Uniunii Scriitorilor din Republica Moldova (1998), Premiul revistei Cuv`ntul Superlativele anului (1998). I s-a decernat un Premiu Special al Uniunii Scriitorilor (1992) [i este laureatul Premiului ALA pe anul 2001. www.polirom.ro © 2006 by Editura POLIROM Editura POLIROM Ia[i, B-dul Carol I nr. 4, P.O. BOX 266, 700506 Bucure[ti, B-dul I.C. Br\tianu nr. 6, et. -

11012411.Pdf

Alma Mater Studiorum – Università di Bologna DOTTORATO DI RICERCA Cooperazione Internazionale e Politiche per lo Sviluppo Sostenibile International Cooperation and Sustainable Development Policies Ciclo XX Settore/i scientifico disciplinari di afferenza: Storico, politico e sociale SPS/13 DEVELOPMENT DISCOURSE IN ROMANIA: from Socialism to EU Membership Presentata da: Mirela Oprea Coordinatore Dottorato Relatore Prof. Andrea Segrè Prof. Stefano Bianchini Esame finale anno 2009 - 2 - EXECUTIVE SUMMARY With their accession to the European Union, twelve new countries - Romania among them - (re)entered the international community of international donors. In the history of development aid this can be seen as a unique event: it is for the first time in history that such a large number of countries become international donors, with such short notice and in such a particular context that sees some scholars announcing the ‘death’ of development. But in spite of what might be claimed regarding the ‘end’ of the development era, development discourse seems to be rather vigorous and in good health: it is able to extert an undeniable force of attraction over the twelve countries that, in a matter of years, have already convinced themselves of its validity and adhered to its main tenets. This thesis collects evidence for improving our understanding of this process that sees the co-optation of twelve new countries to the dominant theory and practice of development cooperation. The evidence collected seems to show that one of the tools employed by the promoters of this co-optation process is that of constructing the ‘new’ Member States as ‘new’, inexpert donors that need to learn from the ‘old’ ones. -

Romanian Book Review Address of the Editorial Office : the Romanian Cultural Institute , Playwrights’ Club at the RCI Aleea Alexandru No

Published by the Romanian Cultural Institute Romanian ditorial by ANDREI Book REORIENMTARTGIOA NS IN EUROPE For several years now, there are percepti- ble cEhanges in our world. In the late eighties, liberal democracy continued the expansion started after World War II, at least in Europe. Meanwhile, national states have weakened, under the pressure to liberalize trade and the fight for recognition of minority (ethnic, poli- Review tical, sexual, etc.) movements. Globalization of the economy, communications, security, ISSUED MONTHLY G No. 5 G JUNE 2013 G DISTRIBUTED FOR FREE knowledge has become a reality. The financial crisis that broke out in 2008 surprised the world organized on market prin- ciples as economic regulator, and threatens to develop into an economic crisis with extended repercussions still hard to detect. U.S. last two elections favored the advocates of “change”, and the policy reorientation of the first world power does not remain without consequences for all mankind. On the stage of the producers of the world, China and Germany are now the first exporters. Russia lies among the powers that cannot be ignored in a serious political approach. (...) What happens, now? Facts cannot be cap- tured only by impressions, perceptions and occasional random experiences, even though many intellectuals are lured by them, produ- cing the barren chatter around us. Systematic TTThhhrrreeeeee DDDaaayyysss WWWiiittthhh thinking is always indispensable to those who want to actually understand what is going on . Not long ago, the famous National Intelligence Council, which, in the U.S., periodically offers interpretations of the global trends, published Global Report 2015 (2008). -

Editions La Traductiere Catalog

1 éditions La Traductière Paris, 2017 Pour nouer encore plus solidement les distances bout à bout, La Traductière s’est lancée, en 2016, dans l’édition de livres. Profil : poésie en traduction. Champ d’action : domaine universel. Teneur : anthologies thématiques, anthologies d’auteur, recueils, revues. Accent d’intensité : du patrimoine à l’extrême contemporain. Notre principe, vous l’aurez compris, est de puiser dans les énormes réserves de la poésie contemporaine afin de la promouvoir en France et dans le monde francophone. Il ne me reste maintenant qu’à vous inviter à découvrir dans les pages du présent catalogue nos ovrages de la rentrée 2017. Auteurs incontournables et recrues de la nouvelle génération – un commando poétique. Linda Maria Baros 3 LITUANIE FRANÇAIS Domaine lituanien. Anthologie poèmes 80 pages La Traductière ISBN : 979-10-97304-05-8 préface et traduction par Jean-Baptiste Cabaud et Ainis Selena Cette anthologie est représentative des multiples mouvements qui traversent et constituent aujourd’hui la poésie lituanienne. Dainius Gintalas se situe à cheval entre le monde occidental et le monde slave. Plutôt dans une lignée de poèmes-fleuves, très rythmés, aux images fortes, il apporte à la poésie de son pays un côté radical. Giedrė Kazlauskaitė, très ancrée dans son époque, est féministe. Son écriture intellectuelle et religieuse s’affranchit volontiers de l’esthétique normée. Dovilė Kuzminskaitė s’inspire des formes et thématiques classiques, mais leur rajoute une dimension ludique et un regard d’une subtilité délicieuse. À la manière peut-être d’un Prévert en France, Liudvikas Jakimavičius oscille entre grande sensibilité poétique, humour et critique. -

Jurnal Contemporan Fluxul Memoriei Prezenta Lucrare Este Un Pamflet Publicistic Şi Trebuie Tratată Ca Atare

Ioan Pînzar Jurnal contemporan Fluxul memoriei Prezenta lucrare este un pamflet publicistic şi trebuie tratată ca atare. Ioan Pînzar Jurnal contemporan Fluxul memoriei Editura MUŞATINII Suceava, 2015 Consiliul Judeţean Suceava Preşedinte: Ioan Cătălin NECHIFOR Vicepreşedinţi: Ilie NIŢĂ, Alexandru RĂDULESCU Centrul Cultural „Bucovina“ Manager: Viorel VARVAROI Secţia pentru Conservarea şi Promovarea Culturii Tradiţionale Suceava Director: Călin BRĂTEANU Editura „Muşatinii” Suceava, str. Tipografiei nr. 1, Tel. 0230 523640, 0757 076885 (I.D.) Director general: Gheorghe DAVID tipar: Motto (mamei): În ce vară? În ce an? Anii trec ca apa. El era drumeţ sărman, Muncitor cu sapa. (George Topîrceanu) 5 Jurnal contemporan n anii luminoşi ai copilăriei mele, când s-a stins din viaţă tovarăşul ÎIosif Vissarionovici Stalin, trăia la Costâna şi mătuşa mea, Ecaterina, abia ieşită din adolescenţă, cu o gropiţă în obraji, cu părul roşu cârlionţat, de o blestemau flăcăii cu cântecul urbanEcaterino, vede-te-aş moartă/ Cu dric la poartă/ Şi cai mascaţi. Mama era înnebunită s-o mărite cu un flăcău bogat. Ea nici să audă. Şi-a găsit un tânăr chipeş, pe care l-a aşteptat să facă armata, s-a măritat şi a dus o lungă viaţă fericită, până ce s-a stins în anul 2012. Tânărul nu era bogat, dar hărnicia lor i-a îmbogăţit cu timpul. Despre generalissimul Stalin nu se putea spune atunci că a murit. S-a stins, a plecat de lângă noi, mă rog, expresii elegante. Ţăranii ar fi spus că a crăpat antihristul, nu credeau incă că va veni colhozul lui Stalin şi la noi. Numai bătrânul Feodor Karamazov, amorezat împreună cu Dimitri, fiul lui, de aceeaşi fată frumoasă şi neserioasă, Gruşenka, a strigat la moartea soţiei sale de-o viaţă, în faţa porţii, pe stradă: a crăpat căţeaua! Cred că la fel ar fi strigat şi genialul Tolstoi, dacă soţia lui nu ar fi fost mai tânără cu 15 ani decât el. -

Motivele De Apel Ale Familiei

B-dul Aviatorilor, nr. 43, sector 1, cod 011853, Bucuresti, ROMANIA Tel: (40-21) 202 5900; Fax: (40-21) 223 3957; 223 0495; E-mail: [email protected]; Website: www.musat.ro INALTA CURTE DE CASATIE SI JUSTITIE - SECTIA PENALA DOSAR PENAL NR.2500/2/2017 Termen de judecata: 21.05.2020 DOMNULE PRESEDINTE, Subsemnatul, URSU ANDREI HORIA si subsemnatele, URSU SORANA si URSU STEFAN OLGA, mostenitori ai defunctului Ursu Gheorghe Emil (fiu, sotie supravietuitoare si, respectiv fiica), in calitate de parti civile in dosarul penal nr.2500/2/2017 al Inaltei Curti de Casatie si Justitie, reprezentati conventional de catre MUSAT & ASOCIATII S.p.a.r.l., cu sediul profesional in Mun. Bucuresti, Bd. Aviatorilor nr. 43, Sector 1, unde, in temeiul art.85 rap. la art.81 alin.1 lit.d C. proc. pen., va solicitam respectuos sa ne fie comunicate toate actele de procedura efectuate in prezenta cauza, In temeiul dispozitiilor art.412 alin.4 C.proc.pen. formulam prezentul: MEMORIU cuprinzand motivele apelului declarat impotriva Sentintei penale nr.196/F/17.10.2019, pronuntata de Curtea de Apel Bucuresti, Sectia I Penala, in dosarul nr.2500/2/2017, solicitandu-va, in temeiul dispozitiilor art.421 alin.2 lit.a) C.proc.pen., pronuntarea unei decizii prin care sa dispuneti admiterea apelului, desfiintarea sentintei apelate si ● condamnarea inculpatului Pirvulescu Marin pentru savarsirea infractiunii de tratamente neomenoase, fapta prevazuta si pedepsita de art.358 alin.1 si 3 Cod penal din 1969; ● condamnarea inculpatului Hodis Vasile pentru savarsirea infractiunii de tratamente neomenoase, fapta prevazuta si pedepsita de art.358 alin.1 si 3 Cod penal din 1969; ● incetarea procesului penal pornit impotriva inculpatului Tudor Postelnicu, in temeiul dispozitiilor art. -

Le Mythe Du « Bon Paysan »

Le mythe du « Bon paysan » De l’utilisation politique d’une figure idéalisée Un travail de : Karel Ziehli [email protected] 079 266 16 57 Numéro d’immatriculation : 11-427-762 Master en Science Politique Mineur en Développement Durable Sous la direction du Prof. Dr. Marc Bühlmann Semestre d’automne 2018 Institut für Politikwissenschaft – Universität Bern Berne, le 8 février 2019 Figure 1 : Photographie réalisée par Gustave Roud, dans le cadre de son travail sur la paysannerie vau- doise (Source : https://loeildelaphotographie.com/fr/guingamp-gustave-roud-champscontre-champs-2016/) Universität Bern – Institut für Politikwissenschaft Karel Ziehli Travail de mémoire Automne 2018 « La méthode s’impose : par l’analyse des mythes rétablir les faits dans leur signification vraies. » Jean-Paul Sartre, 2011 : 13 An meine Omi, eine adlige Bäuerin 2 Universität Bern – Institut für Politikwissenschaft Karel Ziehli Travail de mémoire Automne 2018 Résumé La politique agricole est souvent décrite comme étant une « vache sacrée » en Suisse. Elle profite, en effet, d’un fort soutien au sein du parlement fédéral ainsi qu’auprès de la population. Ce soutien se traduit par des mesures protectionnistes et d’aides directes n’ayant pas d’équivalent dans les autres branches économiques. Ce statut d’exception, la politique agricole l’a depuis la fin des deux guerres mondiales. Ce présent travail s’in- téresse donc aux raisons expliquant la persistance de ce soutien. Il a été décidé de s’appuyer sur l’approche développée par Mayntz et Scharpf (2001) – l’institutionnalisme centré sur les acteurs – et de se pencher sur le mythe en tant qu’institution réglementant les interactions entre acteurs (March et Olsen, 1983). -

Ministru Ministerul De Interne Mihai Chițac Doru-Viorel Ursu Victor

Ministru Ministerul de interne Mihai Chi țac Doru-Viorel Ursu Victor Babiuc George-Ioan Dănescu Doru-Ioan Tărăcilă Gavril Dejeu Constantin-Dudu Ionescu Ioan Rus Marian Săniu ță Vasile Blaga Cristian David Gabriel Oprea Liviu Dragnea Dan Nica Vasile Blaga Vasile Blaga Traian Iga ș Gabriel Berca Ioan Rus Mircea Du șa Radu Stroe Gabriel Oprea Petre Tobă Drago ș Tudorache Media mandatului la Interne Ministerul de externe Sergiu Celac Adrian Năstase Teodor Mele șcanu Adrian Severin Andrei Ple șu Petre Roman Mircea Geoană Mihai Răzvan Ungureanu Călin Popescu Tăriceanu Adrian Cioroianu Lazăr Comănescu Cristian Diaconescu Cătălin Predoiu (interimar) Theodor Baconschi Cristian Diaconescu Andrei Marga Titus Corlă țean Teodor Mele șcanu Bogdan Aurescu Lazăr Comănescu Media mandatului la Externe Ministerul finantelor Ion Pă țan Theodor Stolojan Eugen Dijmărescu George Danielescu Florin Georgescu Mircea Ciumara Daniel Dăianu Decebal Traian Reme ș Mihai Nicolae Tănăsescu Ionu ț Popescu Sebastian Vlădescu Varujan Vosganian Gheorghe Pogea Sebastian Vlădescu Gheorghe Ialomi țianu Bogdan Alexandru Drăgoi Florin Georgescu Daniel Chi țoiu Ioana Petrescu Darius Bogdan Vâlcov Victor Ponta Eugen Teodorovici Anca Paliu Dragu Viorel Ștefan Ionu ț Mișa Media mandatului la Finan țe Educatie Andrei Marga Ecaterina Andronescu Alexandru Athanasiu Mircea Miclea Mihai Hărdău Cristian Adomni ței Anton Anton Daniel Funeriu Cătălin Baba Liviu Pop Ecaterina Andronescu Remus Pricopie Sorin Cîmpeanu Adrian Curaj Mircea Dumitru Pavel Nastase Liviu Pop Media mandatului la Educatie