Insights Volume 1 Number 4

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

65 Tax L. Rev. 241 2011-2012

DATE DOWNLOADED: Sun Sep 26 04:12:46 2021 SOURCE: Content Downloaded from HeinOnline Citations: 65 Tax L. Rev. 241 2011-2012 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at https://hn3.giga-lib.com/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your license, please use: Copyright Information The Case for a "Super-Matching" Rule YARON Z. REICH* I. Introduction ............................................ 242 II. Overview of Matching and Mismatches ................. 245 III. The Matching Concept and Mismatches in Various A reas ................................................... 248 A. Character: Capital vs. Ordinary .................... 248 B . T im ing .............................................. 251 C. Hedging, Straddles, and Other Approaches to Matching Character and Timing .................... 254 1. Hedging Transactions ........................... 254 2. Section 475 ..................................... 260 3. Straddles ........................................ 263 4. Foreign Currency Hedging Transactions ........ 265 D. International Tax Provisions ........................ 268 1. Source .......................................... 269 a. In G eneral .................................. 269 b. Interest Expense ............................ 270 c. Interest Equivalents ........................ 274 d. Foreign Currency Sourcing Rules ........... 274 e. Personal -

Going from the Frying Pan Into the Fire? a Critique of the U.S. Treasury's Newly Proposed Section 987 Currency Regulations Joseph Tobin

University of Miami Law School Institutional Repository University of Miami Business Law Review 10-1-2008 Going from the Frying Pan into the Fire? A Critique of the U.S. Treasury's Newly Proposed Section 987 Currency Regulations Joseph Tobin Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.law.miami.edu/umblr Part of the Taxation-Federal Commons Recommended Citation Joseph Tobin, Going from the Frying Pan into the Fire? A Critique of the U.S. Treasury's Newly Proposed Section 987 Currency Regulations, 17 U. Miami Bus. L. Rev. 211 (2008) Available at: http://repository.law.miami.edu/umblr/vol17/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Miami Business Law Review by an authorized administrator of Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GOING FROM THE FRYING PAN INTO THE FIRE? A CRITIQUE OF THE U.S. TREASURY'S NEWLY PROPOSED SECTION 987 CURRENCY REGULATIONS JOSEPH TOBIN* INTRODUCTION .............................. 213 II. A BRIEF HISTORY OF U.S. TAXATION OF CURRENCY GAINS AND LOSSES ............................ 217 A. Chaos in the Courts: The Early Case Law on Taxation of Currency Gains and Losses .................. 217 1. Bowers v. Kerbaugh-Empire Co .......... 217 2. B.F. Goodrich Co. v. Commissioner ..... 218 3. KVP Sutherland Paper Co. v. United States 219 4. International Flavors & Fragrances v. Commissioner ....................... 220 B. The IRS's Administrative Response: Revenue Ruling 75-106 and Revenue Ruling 75-107 ....... 222 1. Revenue Ruling 75-106 and the "Net Worth M ethod". -

Tax Planning for Foreign Expansion by U.S. Petroleum Companies

Journal of Natural Resources & Environmental Law Volume 13 Issue 1 Journal of Natural Resources & Article 2 Environmental Law, Volume 13, Issue 1 January 1997 Tax Planning for Foreign Expansion by U.S. Petroleum Companies Martin Van Brauman United States Internal Revenue Service Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/jnrel Part of the Oil, Gas, and Mineral Law Commons, Taxation-Transnational Commons, and the Tax Law Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Van Brauman, Martin (1997) "Tax Planning for Foreign Expansion by U.S. Petroleum Companies," Journal of Natural Resources & Environmental Law: Vol. 13 : Iss. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/jnrel/vol13/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Natural Resources & Environmental Law by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TAx PLANNING FOR FOREIGN EXPANSION BY U.S. PETROLEUM COMPANIES MARTIN VAN BRAUMAN* I. INTRODUCTION The purpose of this article is to provide a basic overview of the tax planning considerations for expansion in foreign petroleum exploration and production operations by U.S. oil companies, with two typical examples of reorganizing foreign branches of U.S. corporations into foreign corporations. U.S. companies have many options in deciding how to begin and expand foreign operations--from the debt capitalization and financing of a foreign entity to the contribution of property to a foreign entity. -

Income-Tax Purposes and Not for Transfer-Tax Purposes, and Vice Versa • There Is No “Perfect” Holding Structure for U.S

Texas Tax Lawyer A Tax Journal Winter 2016 • Vol. 43 • No. 2 www.texastaxsection.org TABLE OF CONTENTS FROM OUR LEADER: Click on title to jump to article • The Chair's Message Alyson Outenreath, Texas Tech University, School of Law UPCOMING CLE EVENTS: • Annual Property Tax Seminar April 25, 2016 – Austin, Texas • Tax Section Annual Meeting CLE June 17, 2016 – Fort Worth, Texas SPECIAL ATTENTION: • Submit a Nomination – Outstanding Texas Tax Lawyer Award Nomination Form • Apply Today – Law Student Scholarship Application SPECIAL RECOGNITIONS: • Congratulations to the 2016 Texas Tax Legend Stanley Blend, San Antonio • Hats Off to the 2016-2017 Leadership Academy Class ARTICLES: • New Partnership Tax Audit Rules Michael J. Donahue, Gardere • S Corporation Opportunities and Pitfalls Christina A. Mondrik, Mondrik & Associates 1 • Where is my Secret Decoder Ring? Decoding and Applying Local Tax Rates Christina A. Mondrik, Mondrik & Associates • Who Can Sign Tax Returns and Make Tax Elections: A review of who has signature authority to file tax returns and make tax elections Kenneth S. Freed, Crady, Jewett & McCulley, LLP • New Allocation Regulations Provide Flexibility for Issuers of Tax Exempt Bonds Peter D. Smith, Norton Rose Fulbright • Resurgence of EOR Credits: Oil Tax Planning Opportunity Drew Willey, Drew Willey Law • EEOC’s Attempt to Regulate Employer Instituted Wellness Plan Struck Down Alexia Noble, Polsinelli, PC Henry Talavera, Polsinelli, PC • Addressing the Corporate Inversion Loophole: A Proposal to Redefine Domestic Corporation Status Sara Anne Giddings, Smith Rose Finley, P.C. PRACTITIONER’S CORNER: • Materials from the 18th Annual International Tax Symposium o U.S. International Tax Developments James P. -

Technical Explanation of Division C of H.R. 3221, the Housing Assistance

TECHNICAL EXPLANATION OF DIVISION C OF H.R. 3221, THE “HOUSING ASSISTANCE TAX ACT OF 2008” AS SCHEDULED FOR CONSIDERATION BY THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ON JULY 23, 2008 Prepared by the Staff of the JOINT COMMITTEE ON TAXATION July 23, 2008 JCX-63-08 CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1 I. EXPLANATION OF THE BILL.............................................................................................. 2 TITLE I – BENEFITS FOR MULTI-FAMILY LOW-INCOME HOUSING ............................... 2 A. Low-Income Housing Credit .............................................................................................. 3 1. Temporary increase in the low-income housing credit volume limits (sec. 3001 of the bill and sec. 42 of the Code).............................................................. 3 2. Determination of credit rate (sec. 3002 of the bill and sec. 42 of the Code) ................ 4 3. Modifications to definition of eligible basis (sec. 3003 of the bill and sec. 42 of the Code)................................................................................................................... 5 4. Other simplification and reform of low-income housing tax incentives (sec. 3004 of the bill and sec. 42 of the Code)............................................................ 11 5. Treatment of Basic Housing Allowances for purposes of income eligibility rules (sec. 3005 of the bill and sec. 42 of the Code)........................................................... -

Gains and Losses from Foreign Currency Hedges After Arkansas Best Corp

Journal of Civil Rights and Economic Development Volume 4 Issue 2 Volume 4, 1989, Issue 2 Article 3 Gains and Losses From Foreign Currency Hedges After Arkansas Best Corp. v. Commissioner John Ferretti Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/jcred This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Civil Rights and Economic Development by an authorized editor of St. John's Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SUPREME COURT RAMIFICATIONS GAINS AND LOSSES FROM FOREIGN CURRENCY HEDGES AFTER ARKANSAS BEST CORP. v. COMMISSIONER The economic growth of the United States is dependent upon the successful competition of its business enterprises in the global marketplace.' Although foreign markets provide great opportu- nity, the turbulence of the foreign exchange markets is a signifi- cant drawback.' Fluctuations in foreign currency exchange rates See Comment, United States Regulation of Foreign Currency Futures and Options Trading: Hedging for Business Competitiveness, 8 Nw. J. INT'L L. & Bus. 405, 405 (1987) Ihereinafter Business Competitiveness]. This author notes that due to the export trade deficit experienced annually by this country, Congress has been encouraging United States businesses to com- pete with their foreign counterparts as a means of remedying the trade imbalance. Id. See also Aland, The Treasury Report on Tax Havens - A Response, 59 TAXES 993, 993 n.l (1981) (showing growth of U.S. investment in foreign countries): Business Competitiveness, supra, at 415 n.72 (as of 1987 more enterprises were competing in the international marketplace than at any previous time). -

1111I NEW YORK ST ATE BAR ASSOCIA TION NYSBA One Elk Street, Albany, New York 12207 • 518.463.3200 •

0 " 1111I NEW YORK ST ATE BAR ASSOCIA TION NYSBA One Elk Street, Albany, New York 12207 • 518.463.3200 • www.nysba.org TAX SECTION MEMBERS-AT-LARGE OF EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE S. Douglas Borisky Robert J. Levinsohn Charles M. Morgan Andrew P. Solomon 2010-2011 Executive Committee Kathleen L. Ferrell Lisa A. Levy David M. Schizel Eric Solomon PETER H. BLESSING Marcy G. Geller Vadim Mahmoudov Peter F. G. Schuur Chair Charles I. Kingson Gary B. Mandel Ansgar Simon Shearman & Sterling LLP Stephen Land Douglas McFadyen Eric Sloan 599 Lexington Avenue 11" Floor New York, NY 10022 2121848·4106 JODI J. SCHWARTZ September 29, 2010 First Vice·Chair 2121403·1212 ANDREW W. NEEDHAM Second Vice·Chair The Honorable Max Baucus, The Honorable Charles E. Grassley, 2121474-1440 Chairman Ranking Minority Member DIANA L. WOLLMAN Secretary Committee on Finance Committee on Finance 2121558·4055 COMMITTEE CHAIRS: US Senate US Senate Bankruptcy and Operating Losses Stuart J. Goldring Washington, DC 20510 Washington, D.C. 20510 Russell J. Kestenbaum Compliance, Practice & Procedure Elliot Pisem The Honorable Dave Camp Bryan C. Skarlatos The Honorable Sander E. Levin, Consolidated Returns Chairman Ranking Minority Member Lawrence M. Garrett Edward E. Gonzalez Comm ittee on Ways and Means Committee on Ways and Means Corporations David R. Sicular US House of Representatives US House of Representatives Karen Gilbreath Sowell Cross· Border Capital Markets Washington, DC 20515 Washington, DC 20515 And rew Walker Gordon Wamke Employee Benefits The Honorable William J. Wilkins Regina Olshan The Honorable Douglas H. Shulman Andrew L. Oringer Commissioner Chief Counsel Estates and Trusts Amy Heller Internal Revenue Service Internal Revenue Service Jeffrey N. -

Winter 2013 Committee on Government Submissions

Winter 3 40 2 3 TO MOVE DIRECTLY TO AN ARTICLE CLICK ON THE TITLE TABLE OF CONTENTS FROM OUR LEADER: • The Chair's Message Tina R. Green, Capshaw Green PLLC SPECIAL RECOGNITIONS, UPCOMING EVENTS, AND SECTION INFORMATION: • 2013 Texas State Bar Tax Section Annual Meeting • 2013 Texas State Bar Tax Section Annual Meeting Sponsorship Form • Leadership Academy Graduates ARTICLES: • Catching the Leprechaun: Potential pitfalls and perplexing problems with finding the now-permanent portability pot-of-gold Christian S. Kelso, Malouf, Lynch, Jackson & Swinson P.C. • Defined-Value Transfers Stephen T. Dyer and Richard Ramirez, Baker Botts L.L.P. • Estate Planning Issues With Intra-Family Loans and Notes Steve R. Akers, Bessemer Trust; Philip J. Hayes, First Republic Trust Company • Are The Passive Loss Material Participation Regulations Invalid? Dan G. Baucum, Shakelford, Melton & McKinley • The Tax Court Pro Bono Program Bob Probasco, Thompson & Knight LLP 50606151.1 TEXAS TAX LAWYER – WINTER 2013 COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT SUBMISSIONS: • State Bar of Texas, Section of Taxation Comments to Internal Revenue Service on Proposed Regulation Relating to Circular 230 (REG-138367-06), December 14, 2012 David Gair, Looper Reed & McGraw P.C. David Colmenero, Meadows, Collier, Reed, Cousins & Blau, LLP Shawn R. O’Brien, Mayer Brown, LLP • State Bar of Texas, Section of Taxation Comments to Office of Health Plan Standards and Compliance Assistance, Employee Benefits Security Administration on Proposed Regulations Relating to Incentives for Nondiscriminatory Wellness Programs in Group Health Plans, January 25, 2013 Henry Talavera, Polsinelli Shughart PC 15TH ANNUAL INTERNATIONAL TAX SYMPOSIUM, NOVEMBER 1, 2012: • International Tax Update David L. -

Internal Revenue Bulletin No

IRB 1998-33 8/12/98 11:04 AM Page 1 Internal Revenue Bulletin No. 1998–33 bulletin August 17, 1998 HIGHLIGHTS OF THIS ISSUE These synopses are intended only as aids to the reader in identifying the subject matter covered. They may not be relied upon as authoritative interpretations. INCOME TAX EMPLOYMENT TAX Rev. Rul. 98–39, page 4 Notice 98–43, page 13. All events test; cooperative advertising. Under the all Tax Court review of worker classification and section events test of section 461 of the Code, an accrual method 530 determinations. This notice describes new proce- manufacturer’s liability for cooperative advertising services dures that the Service has implemented to comply with new of a retailer is incurred in Year 1, the year the services are section 7436 of the Code. performed, provided the manufacturer is able to reasonably estimate the liability, even though the retailer does not sub- ADMINISTRATIVE mit the required claim form until Year 2. Rev. Proc. 97–37 modified and amplified. Notice 98–39, page 11. Church plans; nondiscrimination; safe harbors. This no- Rev. Rul. 98–40, page 4. tice extends the effective date of the applicable nondiscrimi- Fringe benefits aircraft valuation formula. For pur- nation regulations for certain church plans. poses of section 1.61–21(g) of the Income Tax Regulations, relating to the rule for valuing noncommercial flights on em- Notice 98–41, page 12. ployer-provided aircraft, the Standard Industry Fare Level 1998 enhanced oil recovery credit. The enhanced oil (SIFL) cents-per-mile rates and terminal charges in effect for recovery credit for taxable years beginning in the 1998 cal- the second half of 1998 are set forth. -

Al Tax Section987 Jan17.Pdf

Tax News and Developments North America Client Alert Treasury Releases Final & Temporary Section 987 January 9, 2017 Branch Currency Translation Regulations Subpart J of the Code governs the recognition of currency gains and losses and translation of certain assets from one currency environment to another. 1 Specifically, under Code Section 989, individuals, corporations, and the "qualified business units" or "QBUs" that they own must have a "functional currency" in which he/she/it computes profit or loss. In broad strokes, Subpart J of the Code attempts to address what happens when a taxpayer or its QBU engages in a transaction that is denominated in a currency other than its functional currency (a.k.a., a "non-functional currency"). Subpart J also addresses what happens when assets, liabilities, profit or loss need to be translated from one functional currency environment to another. EXAMPLE: U.S. Corp is a domestic corporation that owns all of the outstanding shares of a UK private limited company ("UKDRE") that conducts a business and has elected to be treated as a disregarded entity for U.S. tax purposes. UKDRE uses the British pound as its functional currency and UKDRE borrows Euros from an unrelated party bank. In the foregoing example, Code Section 988 governs the computation of UKDRE's recognition of foreign currency gain or loss on the repayment of the Euro borrowing from the bank. This provision measures UKDRE's transaction- based foreign currency gain or loss in pounds. Yet, USCO owns UKDRE, UKDRE's profit and loss flow up to USCO, and USCO has to file its U.S. -

Character of Exchange Gain Or Loss on Currency Transactions

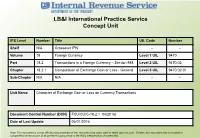

LB&I International Practice Service Concept Unit IPS Level Number Title UIL Code Number Shelf N/A Crossover IPN – – Volume 18 Foreign Currency Level 1 UIL 9470 Part 18.2 Transactions in a Foreign Currency – Section 988 Level 2 UIL 9470.02 Chapter 18.2.1 Computation of Exchange Gain or Loss - General Level 3 UIL 9470.02-01 Sub-Chapter N/A N/A – – Unit Name Character of Exchange Gain or Loss on Currency Transactions Document Control Number (DCN) FCU/CU/C-18.2.1_04(2016) Date of Last Update 06/01/2016 Note: This document is not an official pronouncement of law, and cannot be used, cited or relied upon as such. Further, this document may not contain a comprehensive discussion of all pertinent issues or law or the IRS's interpretation of current law. DRAFT Table of Contents (View this PowerPoint in “Presentation View” to click on the links below) General Overview Facts of Concept Detailed Explanation of the Concept Training and Additional Resources Glossary of Terms and Acronyms Index of Related Issues 2 2 DRAFT General Overview Character of Exchange Gain or Loss on Currency Transactions The functional currency of US taxpayers is generally the US dollar. If a US taxpayer engages in a transaction denominated in nonfunctional currency, it will most likely result in a foreign currency exchange gain or loss, separate from the underlying transaction. A foreign currency exchange gain or loss is the gain or loss realized due to the change in exchange rates between the booking date and the payment date of a transaction involving an asset or liability denominated in a nonfunctional currency. -

Study of the Overall State of the Federal Tax System and Recommendations for Simplification, Pursuant to Section 8022(3)(B) of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986

[JOINT COMMITTEE PRINT] STUDY OF THE OVERALL STATE OF THE FEDERAL TAX SYSTEM AND RECOMMENDATIONS FOR SIMPLIFICATION, PURSUANT TO SECTION 8022(3)(B) OF THE INTERNAL REVENUE CODE OF 1986 VOLUME II: RECOMMENDATIONS OF THE STAFF OF THE JOINT COMMITTEE ON TAXATION TO SIMPLIFY THE FEDERAL TAX SYSTEM Prepared by the Staff of the Joint Committee on Taxation April 2001 U.S. Government Printing Office Washington: 2001 JCS-3-01 JOINT COMMITTEE ON TAXATION 107TH CONGRESS, 1ST SESSION ___________ HOUSE SENATE WILLIAM M. THOMAS, California CHARLES E. GRASSLEY, Iowa Chairman Vice Chairman PHILIP M. CRANE, Illinois ORRIN G. HATCH, Utah E. CLAY SHAW, JR., Florida FRANK H. MURKOWSKI, Alaska CHARLES B. RANGEL, New York MAX BAUCUS, Montana FORTNEY PETE STARK, California JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER, IV, West Virginia Lindy L. Paull, Chief of Staff Bernard A. Schmitt, Deputy Chief of Staff Mary M. Schmitt, Deputy Chief of Staff (i) ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Joint Committee on Taxation study of the overall state of the Federal tax system and recommendations to simplify taxpayer and administrative burdens is required by the IRS Restructuring and Reform Act of 1998 and funded by appropriations approved by the Congress. The study was prepared and produced by virtually the entire Joint Committee staff. Special recognition must be given to Mary Schmitt and Carolyn Smith who helped on every stage of this project, from planning and coordinating staff teams to the final editing of the report. In addition, Rick Grafmeyer, who left the staff last year, was instrumental in assisting in the planning of this report. Cecily Rock, who contributed to various portions of the report, also coordinated the final production of the Joint Committee staff recommendations in Volume II.