Unit 15 Conquest and Appropriation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Name, a Novel

NAME, A NOVEL toadex hobogrammathon /ubu editions 2004 Name, A Novel Toadex Hobogrammathon Cover Ilustration: “Psycles”, Excerpts from The Bikeriders, Danny Lyon' book about the Chicago Outlaws motorcycle club. Printed in Aspen 4: The McLuhan Issue. Thefull text can be accessed in UbuWeb’s Aspen archive: ubu.com/aspen. /ubueditions ubu.com Series Editor: Brian Kim Stefans ©2004 /ubueditions NAME, A NOVEL toadex hobogrammathon /ubueditions 2004 name, a novel toadex hobogrammathon ade Foreskin stepped off the plank. The smell of turbid waters struck him, as though fro afar, and he thought of Spain, medallions, and cork. How long had it been, sussing reader, since J he had been in Spain with all those corkoid Spanish medallions, granted him by Generalissimo Hieronimo Susstro? Thirty, thirty-three years? Or maybe eighty-seven? Anyhow, as he slipped a whip clap down, he thought he might greet REVERSE BLOOD NUT 1, if only he could clear a wasp. And the plank was homely. After greeting a flock of fried antlers at the shevroad tuesday plied canticle massacre with a flash of blessed venom, he had been inter- viewed, but briefly, by the skinny wench of a woman. But now he was in Rio, fresh of a plank and trying to catch some asscheeks before heading on to Remorse. I first came in the twilight of the Soviet. Swigging some muck, and lampreys, like a bad dram in a Soviet plezhvadya dish, licking an anagram off my hands so the ——— woundn’t foust a stiff trinket up me. So that the Soviets would find out. -

IGNOU Modern World History

MHI-02 Modern World : [32] Block-1 Theories of the Modern World : [3] Unit-1 Renaissance and the Idea of the Individual Unit-2 The Enlightenment Unit-3 Critiques of Enlightenment Block-2 Modern World: Essential Components : [3] Unit-4 Theories of the State Unit-5 Capitalist Economy and its Critique Unit-6 The Social Structure Block-3 The Modern State and Politics : [4] Unit-7 Bureaucratization Unit-8 Democratic Politics Unit-9 Modern State and Welfare Unit-10 Nationalism Block-4 Capitalism and Industrialization : [4] Unit-11 Commercial Capitalism Unit-12 Capitalist Industrialization Unit-13 Socialist Industrialization Unit-14 Underdevelopment Block-5 Expansion of Europe : [5] Unit-15 Conquest and Appropriation Unit-16 Migrations and Settlements Unit-17 Imperialism Unit-18 Colonialism Unit-19 Decolonization Block-6 International Relations : [3] Unit-20 Nation-State System Unit-21 International Rivalries of Twentieth Century Unit-22 The Unipolar World and Counter-Currents Block-7 Revolutions : [4] Unit-23 Political Revolution: France Unit-24 Political Revolution: Russia Unit-25 Knowledge Revolution: Printing and Informatics Unit-26 Technological Revolution: Communications and Medical Block-8 Violence and Repression : [3] Unit-27 Modern Warfare Unit-28 Total War Unit-29 Violence by Non-State Actors Block-9 Dilemmas of Development : [3] Unit-30 Demography Unit-31 Ecology Unit-32 Consumerism UNIT 1 RENAIASSANCE AND THE IDEA OF THE INDIVIDUAL Structure 1.1 Introduction 1.2 The Invention of the Idea 1.3 Developments in Italy 1.4 New Groups: Lawyers and Notaries 1.5 Humanism 1.6 New Education 1.7 Print 1.8 Secular Openings 1.9 Realism vs. -

130536601.Pdf

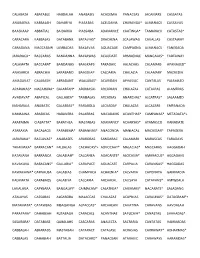

CALABAZA ABATABLE HABDALAH ANABASIS ACADEMIA PANACEAS JACAMARS CASSATAS ANABAENA KABBALAH DAHABIYA PIASABAS ACELDAMA CHARANGA* ALMANACK CASSAVAS BAASKAAP ABBATIAL BAIDARKA PIASSABA ADAMANCE CAATINGA* TAMARACK CATASTAS* CARACARA KABBALAS DATABANK BATAVIAS* DRACAENA SCALAWAG CAVALLAS CASTAWAY CARAGANA MACCABAW LAMBADAS BAKLAVAS AQUACADE CAMPAGNA ALMANACS FANEGADA JARARACA* BACCARAS BANDANNA BAKLAWAS ACAUDATE ARMAGNAC MANCALAS* FADEAWAY CALAMATA BACCARAT BANDANAS BAASKAPS FARADAIC HALACHAS CALAMARS APANAGED* ANASARCA ABRACHIA SARABAND BAASSKAP CALDARIA CHALAZIA CALAMARY MAZAEDIA AMADAVAT CALABASH ABRADANT WALLABAS* ACARIDAN APHASIAC CANTALAS PAJAMAED APADANAS* MACAHUBA* GALABEAH* ABOMASAL ARCADIAN CHALAZAL CATALPAS ALAMEDAS AVADAVAT ABAPICAL GALLABEA* TAMBALAS ARCADIAS ANARCHAL* ALCATRAS* SALAAMED MAHARAJA ANABATIC GALABEAS* PARABOLA LACKADAY CHALAZAS ALCAZARS EMPANADA KAMAAINA ARABICAS HABANERA PALABRAS MACADAMS ACANTHAS* CAMPANAS* METADATA*+ ARAPAIMA CIABATTA* BARATHEA MASTABAS ADAMANCY ACHARYAS* ATAMASCO VANADATE ATARAXIA BACALAOS PARABEMA* RABANNAS* ANACONDA MANIACAL MACASSAR* TAPADERA JARARAKA* BACLAVAS* ANABASES ARAROBAS SANDARAC CALAMARI MARASCAS FARADAYS TAKAMAKA* BARRACAN* FALBALAS CACHACAS*+ ADVOCAAT* MALACIAS* MASCARAS HAGGADAH KATAKANA BARRANCA GALABIAH* CALCANEA AGACANTE* ALOCASIA* AMARACUS* AGGADAHS KAVAKAVA BARACANS* GALLABIA* CARAPACE AGUACATE CARPALIA CARANNAS* HAGGADAS KAWAKAWA* CARNAUBA GALABIAS CHAMPACA ACHAENIA* CALVARIA CAPONATA GAMMADIA KALAMATA CARABAOS GALABIYA CALCARIA ARCHAEAL CALISAYA CATAPANS* AMYGDALA LAVALAVA -

A General History of the Pyrates

his fixed Resolution to have blown up together, when he foundno possibility of escaping. When the Lieutenant came to Bath-Town, he made bold to seize in the Governor’s Store-House, the sixty Hogsheads of Sugar, and from honest Mr. Knight, twenty; which it seems was their Dividend A General History of the of the Plunder taken in the French Ship; the latter did not long sur- Pyrates vive this shameful Discovery, for being apprehensive that he might be called to an Account for these Trifles, fell sick with the Fright, from their first rise and settlement in the island of and died in a few Days. Providence, to the present time After the wounded Men were pretty well recover’d, the Lieu- tenant sailed back to the Men of War in James River, in Virginia, with Black-beard’s Head still hanging at the Bolt-sprit End, and Captain Charles Johnson fiveteen Prisoners, thirteen of whom were hanged. It appearing upon Tryal, that one of them, viz. Samuel Odell, was taken out of the trading Sloop, but the Night before the Engagement. This poor Fellow was a little unlucky at his first entering upon his new Trade, there appearing no less than 70 Wounds upon him after the Action, notwithstanding which, he lived, and was cured of them all. The other Person that escaped the Gallows, was one Israel Hands, the Master of Black-beard’s Sloop, and formerly Captain of the same, before the Queen Ann’s Revenge was lost in Topsail Inlet. The aforesaid Hands happened not to be in the Fight, but was taken afterwards ashore at Bath-Town, having been sometime be- fore disabled by Black-beard, in one of his savage Humours, af- ter the following Manner.—One Night drinking in his Cabin with Hands, the Pilot, and another Man; Black-beard without any Provo- cation privately draws out a small Pair of Pistols, and cocks them under the Table, which being perceived by the Man, he withdrew and went upon Deck, leaving Hands, the Pilot, and the Captain to- gether. -

The Words of the Champions for 2021

2 O 2 1 CELEBRATING CHAMPIONS OF THE WORDS! gladiolus [glad-ee-OHL-us] noun stichomythia bougainvillea [sti-kuh-MITH-ee-uh] [boo-gun-VIL-yuh] noun noun eudaemonic vouchsafe [yoo-dee-MAHN-ik] [vauch-SAYF] adjective verb staphylococci [sta-fuh-loh-KAHK-sahy] plural noun chlorophyll appoggiatura fibranne [KLOR-uh-fil] [uh-pah-juh-TOO-ruh] [FAHY-bran] noun noun noun interlocutory [in-tur-LAHK-yuh-tor-ee] adjective cymotrichous [sahy-MAH-tri-kus] adjective insouciant smaragdine [in-SOO-see-unt] [smuh-RAG-dun] adjective adjective logorrhea [lah-guh-REE-uh] noun GREETINGS, CHAMPIONS! About this Study Guide Do you dream of winning a school spelling bee, or even attending the Scripps National Spelling Bee? Words of the Champions is the official study resource of the Scripps National Spelling Bee, so you’ve found the perfect place to start. Prepare for a 2020 or 2021 classroom, grade-level, school, district, county, regional or state spelling bee with this list of 4,000 words. All words in this book have been selected by the Scripps National Spelling Bee from our official dictionary,Merriam- Webster Unabridged (http://unabridged.merriam-webster.com). Words of the Champions is divided into three difficulty levels, ranked One Bee (800 words), Two Bee (2,100 words) and Three Bee (1,200 words). These are great words to challenge you, whether you’re just getting started in spelling bees or if you’ve already participated in several. At the beginning of each level, you’ll find theSchool Spelling Bee Study List words. For any classroom, grade-level or school spelling bee, study the 150-word One Bee School Spelling Bee Study List, the 150-word Two Bee School Spelling Bee Study List and the 150-word Three Bee School Spelling Bee Study List: a total of 450 words. -

Eighteenth-Century Gujarat TANAP Monographs on the History of Asian-European Interaction

Eighteenth-Century Gujarat TANAP Monographs on the History of Asian-European Interaction Edited by Leonard Blussé and Cynthia Viallé VOLUME 11 Eighteenth-Century Gujarat The Dynamics of Its Political Economy, 1750-1800 By Ghulam A. Nadri LEIDEN • BOSTON 2009 The TANAP programme is funded by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO). This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Nadri, Ghulam A. Eighteenth-century Gujarat : the dynamics of its political economy, 1750-1800 / by Ghulam A. Nadri. p. cm. — (TANAP monographs on the history of Asian-European interaction, ISSN 1871-6938 ; v. 11) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-17202-9 (hardback : alk. paper) 1. Gujarat (India)--Economic conditions—18th century. 2. Businesspeople—India— Gujarat—History—18th century. 3. Gujarat (India—Politics and government—18th century. I. Title. II. Series. HC437.G85N25 2009 330.954’750296—dc22 2008045747 ISSN 1871-6938 ISBN 978 90 04 17202 9 Copyright 2009 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Brill has made all reasonable efforts to trace all right holders to any copyrighted material used in this work. In cases where these efforts have not been successful the publisher welcomes communications from copyright holders, so that the appropriate acknowledgements can be made in future editions, and to settle other permission matters. -

GIPE-062139.Pdf

J\ttorlJi of §ort .t. Q;-eorge LETTERS FROM TELLICHERRY 1733-34 Volume ill • MADRAS PRI1li'TED BY THE SUPERINTENDENT. GOVERNMENT PRESS 'J 1, L : grn:lt'?S>l.. ~ 6;4 t !> .' , PREFATORY NOTE ';I.'his volume conta.ins the letters sent from Tellicherry from October 1733 to September 1734 and is the third in the series of records known as "Letters from Tellicherry." The manuscript volume has been mended and is in a fair state of preservation. N. KELU NAIR, EGMORE, Assistant Ourator-in-Okarge, 9th August 1934. Madras Record Office. RECORDS OF FORT ST. GEORGE LETTERS FROM TELLICHERRY 1733-34 (VOLUME No.3) To THE HONBLE ROBERT COWAN ESQB. PRESIDENT AND GOVERNOUR &0".· COUNOILL ON BOMBAY. HONBLE SIR & Sms . Since our last of the 15th: Ultimo Via Goa Triplicate whereof goes now We have received your Commands of the 11th. September' Shybar the 23d, Ditto. and another of the 28th• of said Month.' Princess of Wales, who imported the 23d , Instant at Night. We shall be mindfull to recover of the Supra Cargoes of the Canton Merchant the Value of thirty Baggs Paddy short delivered us, and we hope when the Paddy we kept in Store is delivered out, no considerable Loss will arise, as We have taken the outmost Care to prevent it. The Newcastle arrived the 20th, Instant and sailed that day after landing Six Chests of Treasure containing Sixty th:0usand Rupees for Callicutt, to take on board the Eighteen thousand feet of Plank, and the Stick lying there in readiness for Gombroon Factory, but we understand She is gone to Cochin for Provisions, and ~ay speedily be expected .back, when. -

J825js4q5pzdkp7v9hmygd2f801.Pdf

INDEX S. NO. CHAPTER PAGE NO. 1. ANCIENT INDIA - 1 a. STONE AGE b. I. V. C c. PRE MAURYA d. MAURYAS e. POST MAURYAN PERIOD f. GUPTA AGE g. GUPTA AGE h. CHRONOLOGY OF INDIAN HISTORY 2. MEDIVAL INDIA - 62 a. EARLY MEDIEVAL INDIA MAJOR DYNASTIES b. DELHI SULTANATE c. VIJAYANAGAR AND BANMAHI d. BHAKTI MOVEMENT e. SUFI MOVEMENT f. THE MUGHALS g. MARATHAS 3. MODERN INDIA - 191 a. FAIR CHRONOLOGY b. FAIR 1857 c. FAIR FOUNDATION OF I.N.C. d. FAIR MODERATE e. FAIR EXTREMISTS f. FAIR PARTITION BENGAL g. FAIR SURAT SPLIT h. FAIR HOME RULE LEAGUES i. FAIR KHILAFAT j. FAIR N.C.M k. FAIR SIMON COMMISSION l. FAIR NEHRU REPORT m. FAIR JINNAH 14 POINT n. FAIR C.D.M o. FAIR R.T.C. p. FAIR AUGUST OFFER q. FAIR CRIPPS MISSION r. FAIR Q.I.M. s. FAIR I.N.A. t. FAIR RIN REVOLT u. FAIR CABINET MISSION v. MOUNTBATTEN PLAN w. FAIR GOVERNOR GENERALS La Excellence IAS Ancient India THE STONE AGE The age when the prehistoric man began to use stones for utilitarian purpose is termed as the Stone Age. The Stone Age is divided into three broad divisions-Paleolithic Age or the Old Stone Age (from unknown till 8000 BC), Mesolithic Age or the Middle Stone Age (8000 BC-4000 BC) and the Neolithic Age or the New Stone Age (4000 BC-2500 BC). The famous Bhimbetka caves near Bhopal belong to the Stone Age and are famous for their cave paintings. The art of the prehistoric man can be seen in all its glory with the depiction of wild animals, hunting scenes, ritual scenes and scenes from day-to-day life of the period. -

Twisters Hit Florida Cities

,w ; • • \; DkIIt Nut P fw i Rot ^ * »F TIm Week Knded The Weather , D ecem ber t , IMV Occaaional rain tonight. Tern* erat^rea In ui^>or SOb. T om or 15,563 row cloudy with rain likely. High In 40a. Manchenter^— A City of Village Charm VOL. LXXXVp, NO. 60 (TWENTY-POUR PAGES—TWO SECTIONS) MANCHESTER, pONN., MONDAY, DECEMBER 11, 1967 (Claemiled Adyeitisliig on P a ge *i) PRICE SEVEN CENTS j ’ l State n || w8 Twisters Hit Concert Leads to r/ Florida Cities \ PANAMA CITY, Fla. (AP)— TVirnadoes also hit at smell A rtew tornado watch was issued towns between Panama Olty Arrests today for the Florida Panhan and P ensacola 160 m iles w e s t dle, ravaged Sunday morning One twister smariied Into- the NEW HAVEN, Conn. (AP) — by roaring twisters which lev Alabama * coastline, damaging A rock ’n’ roll concert wocr eled hundreds of homes, killed homes at MlfUn and raking a stopped by p<^ce, the lead sing two and caused more than 97 boatyard in Bon Secour, Ala., er o t the groiq>, “The doors,” million in damages. where the uninsured loss was was dragged off the atage, a few Ten Florida Panhandle cities estimated at 920,000. acuffles broke out and three per- were hit Sunday morning and ’Three-year-old Joan (Joker, aona In the Journalism field residents spent a restless night one of six children dug out o4 were arrested Saturday night. as tornado watches were posted the wreckage of their Fort Wal P olice said Jim M orrison, 24, and then lifted at T a.m. -

Kathiawad Pirates Kachchh Pirates Malabar Pirates S

Table 1: Seafaring Community Indulging in Plundering Kathiawad Pirates Kachchh Pirates Malabar Pirates S. No. Community Place Occupation Community Place Occupation Community Place Occupation Saltwater Bharuch Malabar, Zamorin’s Fishermen 1. MACHHI & - - - KUNJALI Kotte & naval & Sailors Valsad Cochin soldiers KHARWA Veraval, Saltwater KHARWA Mandvi Saltwater Alibag, Fishermen Diu Fishermen Byet, Fishermen Mangaon & 2. Rajput, Cambay, & Sailors Rajput, KHARVI Dwarka & & Sailors & Sailors Koli Surat, Lascar, Koli & Porbandar Lascar Mahad & Muslim Hansot ply-boat Muslim Freshwater All over Fishermen 3. BHOI - Fishermen - - - BHOI Malabar & Sailors & Sailors coast Byet, Diu, Saltwater Mahad Fishermen Dwarka, Fishermen 4. BHADELA BHADELA - Lascar GABIT and & Sailors Jaffrabad, & Sailors Ratnagiri Jamnagar Lascar Saltwater Byet, Fishermen, Halar Fishermen 5. VAGHER VAGHER Dwarka, Pirates & MAPPILA Kerala Seafarers Navanagar & Sailors Okhamandal Freebooter Lascar Nawanagar, Saltwater 6. SANGHAR Khambhaliya Fishermen SANGHAR - - MALABARI Malabar Sailors Porbandar. & Sailors Nongmaithem Keshorjit Singh Page 112 a Table 1: Seafaring Community Indulging in Plundering Saltwater Bombay, Fishermen Fishermen, ANGRIAS Karwar, 7. MIANA Malia MIANA Vavaniya Sailors & Sailors Pirates (MARATHA) Gheria, Lascar Kolaba Saltwater 8. DHEBRA Surat Fishermen - - - - - - & Sailors Kolaba, Byet, Fishermen Fishermen Rahtad, Dwarka, and All over the Sailors & KOLI & 9. KOLI & Sailors KOLI Mangaon Porbandar coast Fishermen Sailors Lascar Bassein & Cheul Diu, KOLI Fishermen 10. Bhavnagar, - - - - - - KHARWA & Sailors Talaja KASBATI Gogha, Surat Fishermen 11. - - - - - - KHARWA & Bharuch & Sailors Fishermen 12. MANEKS Okhamandal - - - - - - & Sailors Mangrol, KABAVA- Fishermen 13. Porbandar - - - - - - LIYA & Sailors & Veraval Source: James Campbell , Hindu and Tribes of Gujarat, Vol. II, 1988 & C. A. Kincaid The Outlaws of Kathiawad and Other Studies, 1905 Nongmaithem Keshorjit Singh Page 112 a Table II: Piracy and Piratal Aggressions Pre- c. -

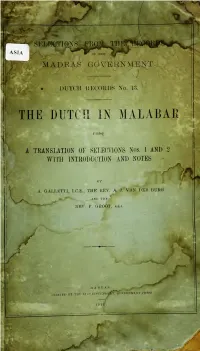

The Dutch in Malabar : Being a Translation of Selections Nos. 1 and 2

r< t^'. T^ j^ ^ >^Kl^WTTGX8^Em|.ra^^ ASIA ^ :. W OF THE raar^; 1. MADEAS G0VBRHM:]^NT • DUTCH UEC0KD8 No. 13. THE DUTCH IN MALABAR r.KISG \ A TRANSLATION OF SELECTIONS Nos. 1 AND 2 WUm INTRODUCTION AND NOTES A. GALLKTTl, I.C.S., THE KEV. A. T. VAN 1>EK BURG AND THt: REV. P. GROOT, 8.8..I. MADRAS: 1911 . IT J 1\5 CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Cornell University Library DS 485.M35A3 The Dutch In Malabar :belng a transiatio 3 1924 023 942 828 \<\ Cornell University Library XI The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924023942828 SELECTIONS FEOM THE RECORDS OF THE MADBAS GOVERNMENT. "^ (^'Pires\c\£t\c DUTCH RECORDS No. 13. THE DUTCH IN MALABAR BEIMG A TRANSLATION OF SELECTIONS Nos. I AND 2 WITH INTRODUCTION AND NOTES BY A. GALLETTI, I.C.S., THE KEY. A. J. VAN DER BURG AND THE REV. P. GROOT, S.S.J. MADRAS: FEINTED BY THE Sni-EKINTENDENT, GOVEENMESTT PBESS. , 1911, V .. CONTENTS OF INTRODUCTION. PAGE I. The Madras Dutch mamiscripts .. ., .. ,. ,. .. .. 1 II. " Memoirs " of the Dutch Chiefs of Malabar 2 III. The Dutch Settlements on the Malahar Coast , . , 3 IV. Foundation of the Dutch Empire in the Bast . 5 v. The taking of Cochin from the Portuguese . 7 VI. Portuguese influences. Fortification and its necessity . „ „ . 15 VII. The Peace with Portugal -* 38 Till. Campaigns of 1717 A.D. and of 1739-42 A.D 19 IX. -

A General History of the Pyrates

coming to attack him, as has been before observed; oneof his Men asked him, in Case any thing should happen to him in the Engagement with the Sloops, whether his Wife knew where he had buried his Money? He answered, That no Body but himself and the Devil, knew where it was, and the longest A General History of the Liver should take all. Pyrates Those of his Crew who were taken alive, told a Story which may appear a little incredible; however, we think it will not be from their first rise and settlement in the island of fair to omit it, since we had it from their own Mouths. That Providence, to the present time once upon a Cruize, they found out that they had a Man on Board more than their Crew; such a one was seen several Days amongst them, sometimes below, and sometimes upon Deck, Captain Charles Johnson yet no Man in the Ship could give an Account who he was, or from whence he came; but that he disappeared little before they were cast away in their great Ship, but, it seems, they verily believed it was the Devil. One would think these Things should induce them to reform their Lives, but so many Reprobates together, encouraged and spirited one another up in their Wickedness, to which a contin- ual Course of drinking did not a little contribute; for in Black- beard’s Journal, which was taken, there were several Memoran- dums of the following Nature, sound writ with his own Hand.— Such a Day, Rum all out:—Our Company somewhat sober:—A damn’d Confusion amongst us!—Rogues a plotting;—great Talk of Separation.—So I look’d sharp for a Prize;—such a Day took one, with a great deal of Liquor on Board, so kept the Company hot, damned hot, then all Things went well again.