Liberian Studies Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Short History of the First Liberian Republic

Joseph Saye Guannu A Short History of the First Liberian Republic Third edition Star*Books Contents Preface viii About the author x The new state and its government Introduction The Declaration of Independence and Constitution Causes leading to the Declaration of Independence The Constitutional Convention The Constitution The kind of state and system of government 4 The kind of state Organization of government System of government The l1ag and seal of Liberia The exclusion and inclusion of ethnic Liberians The rulers and their administrations 10 Joseph Jenkins Roberts Stephen Allen Benson Daniel Bashiel Warner James Spriggs Payne Edward James Roye James Skirving Smith Anthony William Gardner Alfred Francis Russell Hilary Richard Wright Johnson JosephJames Cheeseman William David Coleman Garretson Wilmot Gibson Arthur Barclay Daniel Edward Howard Charles Dunbar Burgess King Edwin James Barclay William Vacanarat Shadrach Tubman William Richard Tolbert PresidentiaI succession in Liberian history 36 BeforeRoye After Roye iii A Short HIstory 01 the First lIberlJn Republlc The expansion of presidential powers 36 The socio-political factors The economic factors Abrief history of party politics 31 Before the True Whig Party The True Whig Party Interior policy of the True Whig Party Major oppositions to the True Whig Party The Election of 1927 The Election of 1951 The Election of 1955 The plot that failed Questions Activities 2 Territorial expansion of, and encroachment on, Liberia 4~ Introduction 41 Two major reasons for expansion 4' Economic -

Mr. Speaker; Mr. President Pro-Tempore; Honorable Members

ANNUAL MESSAGE TO THE FOURTH SESSION OF THE FIFTY-FOURTH NATIONAL LEGISLATURE OF THE REPUBLIC OF LIBERIA DELIVERED BY HIS EXCELLENCY DR. GEORGE MANNEH WEAH PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF LIBERIA THE CAPITOL BUILDING CAPITOL HILL MONROVIA, LIBERIA 25 JANUARY 2021 Madam Vice President and President of the Senate; Mr. Speaker; Mr. President Pro-Tempore; Honorable Members of the Legislature; Your Honor the Chief Justice, Associate Justices of the Supreme Court and Members of the Judiciary; The Dean and Members of the Cabinet and other Government Officials; The Doyen, Excellencies and Members of the Diplomatic and Consular Corps; His Excellency, the Special Representative of the Secretary-General of the United Nations in Liberia; The Officers and Staff of the United Nations Mission in Liberia (UNMIL); The Chief of Staff and Men and Women of the Armed Forces of Liberia (AFL); Former Officials of Government; Traditional Leaders, Chiefs and Elders; Political and Business Leaders; Religious Leaders; Officers and Members of the National Bar Association; Labor and Trade Unions; Civil Society Organizations; Members of the Press; Special Guests; Distinguished Ladies and Gentlemen; Fellow Liberians: In fulfilment of my official duty under the mandate of Article 58 of the Constitution of Liberia, I am here again to present the Administration’s Legislative Program for the ensuing Fourth Session of this Honorable Legislature, and to report to you on the State of the Republic. I am further mandated to present the overall economic condition of the Nation, which should cover both expenditure and income. I want to congratulate all new Senators and Representatives who were elected to this august body from the Senatorial and By-elections held on December 8, 2020. -

Joseph Jenkins Roberts Birthday 2009

A PROCLAMATION BY THE PRESIDENT WHEREAS, it is virtuously befitting that a people and a nation, should recognize and pay homage to persons who contributively make significant impact for the installation of the State, and its perpetuity; and WHEREAS, the Creation of the Republic of Liberia, out of the aspiration of the African and his Descendents was made possible by the combined efforts of Those who came to these shores with Those whom they met here, with Joseph Jenkins Roberts, arriving on 9th February 1829 with the Robert’s Family, including his Mother, who wrote that they were “pleased with the Country and had not the least desire to leave” for any other place; and WHEREAS, Joseph Jenkins Roberts was preeminent in fostering the Movement of the “Colony” to inspire all those concerned resulting in the Declaration of Independence of the Republic of Liberia on July 26, 1847, thus becoming “the Father of the Nation”; and WHEREAS, under his Leadership as Governor from 1822 to 1847, and as President, from 1847 to 1855, and then, from 1871 to 1876, Liberia developed along the West African Coast from the Shebro River to the Pedro River, counting approximately 600 miles of seacoast; and WHEREAS, under the role of an effective and objective Leadership, he substantiated many diplomatic, legal, political and social cornerstones for the continuation of the Republic of Liberia, which have remained as irrepressible and irreplaceable until today, from which our present Republic draws its strength in its independence and sovereign interactions with -

2018-2019 National History Bowl Round 6

NHBB C-Set Bowl 2018-2019 Bowl Round 6 Bowl Round 6 First Quarter (1) This politician was dogged by accusations of an affair with Nan Britton. The Four Power Treaty was signed when this man called the Washington Naval Conference to limit arms. This man, who appointed the first Cabinet member to go to prison, died of a cerebral hemorrhage before the Teapot Dome scandal was brought to light. For ten points, name this US president who promised a \return to normalcy" and was succeeded by Calvin Coolidge. ANSWER: Warren Harding (2) Members of this group in Shanghai organized a seven-day camp at the Moganshan resort. The motto \Blood and Honor" was adopted by this group, which was led by Baldur von Schirach and Artur Axmann. Volkssturm commonly drafted members of this group, one unit of which assisted the Kriegsmarine. An organization similar to this one that was only open to women was the League of German Girls. For ten points, name this organization consisting of boys who assisted the Nazi effort. ANSWER: Hitler Youth (accept Hitlerjugend) (3) An obelisk in this location includes bas-reliefs of eight historical moments and proclaims \Eternal glory to the heroes of the people." While covering an event in this location, a thrown rock nearly killed photographer Jeff Widener. This location's Great Hall of the People contained a banquet hall that Richard Nixon visited during a 1972 visit. A man was shown standing in front of a tank in a photo taken during a 1989 protest in this location. For ten points, name this square in Beijing. -

TRC of Liberia Final Report Volum Ii

REPUBLIC OF LIBERIA FINAL REPORT VOLUME II: CONSOLIDATED FINAL REPORT This volume constitutes the final and complete report of the TRC of Liberia containing findings, determinations and recommendations to the government and people of Liberia Volume II: Consolidated Final Report Table of Contents List of Abbreviations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<............. i Acknowledgements <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... iii Final Statement from the Commission <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<............... v Quotations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 1 1.0 Executive Summary <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 2 1.1 Mandate of the TRC <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 2 1.2 Background of the Founding of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... 3 1.3 History of the Conflict <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<................ 4 1.4 Findings and Determinations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<< 6 1.5 Recommendations <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<... 12 1.5.1 To the People of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 12 1.5.2 To the Government of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<. <<<<<<. 12 1.5.3 To the International Community <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 13 2.0 Introduction <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 14 2.1 The Beginning <<................................................................................................... 14 2.2 Profile of Commissioners of the TRC of Liberia <<<<<<<<<<<<.. 14 2.3 Profile of International Technical Advisory Committee <<<<<<<<<. 18 2.4 Secretariat and Specialized Staff <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 20 2.5 Commissioners, Specialists, Senior Staff, and Administration <<<<<<.. 21 2.5.1 Commissioners <<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<<. 22 2.5.2 International Technical Advisory -

Activity Report Activity MSF

6 MSF International Office Rue de Lausanne 78, Case Postale 116, CH-1211 Geneva 21, Switzerland T (+41-22) 8498 400, F (+41-22) 8498 404, E [email protected], www.msf.org MSF Activity Report 2005/0 MSF Activity Repor t July 2005 – July 20 06 Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) was founded in 1971 by a small group of doctors and journalists who believed that all people should have access to emergency relief. MSF was one of the first nongovernmental organisations to provide urgently needed medical assistance and to publicly bear witness to the plight of the people it helps. Today MSF is an international medical humanitarian movement with branch offices in 19 countries. In 2005, over 2225 MSF volunteer doctors, nurses, other medical professionals, logistical experts, water and sanitation engineers and administrators joined approximately 25,850 locally hired staff to provide medical aid in over 70 countries. MSF was awarded the 1999 Nobel Peace Prize. The Médecins Sans Frontières Charter About this publication FEATURE WRITERS Médecins Sans Frontières is a private international association. Nathalie Borremans, Leopold Buhendwa, Dieudonné Bwirire, Fabien Dubuet, Margaret Fitzgerald, The association is made up mainly of doctors and health C. Foncha, Moses Massaquoi, Marilyn McHarg, Dalitso Minsinde, Rodrick Nalingukgwi, Fasineh Samura, Milton Tectonidis, Emmanuel Tronc sector workers and is also open to all other professions which might help in achieving its aims. COUNTRY TEXT AND SIDEBAR MATERIAL WRITTEN BY Emma Bell, Claude Briade, Lucy Clayton, -

James Kwegyir Aggrey (1875- 1927) Kwegyir Aggrey Was Born in Anomabo

James Kwegyir Aggrey (1875- 1927) Kwegyir Aggrey was born in Anomabo. At the age of eight, he was baptized and given his Christian name James. He also attended the above mentioned Wesleyan elementary school.1 In 1898, the Bishop John Bryan Small (?- 1915) of the “African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Zion Church” (USA) came to Gold Coast. He had been there, before, when he had come from Barbados/ Bahamas as a clerk of the British Army, but had resigned because of British aggression towards the Asante. He then had travelled to the US to become a minister at the AME Zion Church. In Gold Coast, he was looking for educationally qualified young men who would go to the US for training and later return as missionaries. Small stayed for only six years and then returned to the US. Nevertheless, when he died, some of his last words were: "Don't let my African work fail!"2 Small selected Aggrey because he was known to be very bright. Aggrey was brought to Salisbury/ North Carolina and attended the Livingstone College where he graduated in 1902 with three academic degrees. He was appointed minister of the AME Zion Church in Salisbury and married Rose Douglas, a native of Virginia, with whom he had four children. Aggrey began to teach at the college. In 1920, Dr. Paul Monroe,3 professor at Columbia University, offered to him the opportunity to join the otherwise all-white African Education Commission of the Phelps-Stokes Fund4 to assess the educational needs in Africa. Aggrey agreed and started a voyage visiting areas in the today countries Sierra Leone, Liberia, Ghana, Cameroon, Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Angola. -

World Stage Curriculum

World Stage Curriculum Washington Irving’s Tour 1832 TEACHER You have been given a completed world stage and a world stage that your students can complete. This world stage is a snapshot of the world with Oklahoma, Cherokee Nation and Muscogee Creek Nation, at its center. The Pawnee, Comanche, and Kiowa were out to the west. Europe is to the north and east. Africa is to the south and east. South America is south and a bit east. Asia and the Pacific are to the west. Use a globe to show your students that these directions are accurate. Students - Directions 1. Your teacher will assign one of these actors to you. 2. After research, note the age of the actor in 1832, the year that Irving, Ellsworth, Pourtalès, and Latrobe took a Tour on the Oklahoma prairies. 3. Place the name and age of the actor in the right place on the World Stage. 4. Write a biographical sketch about the actor. 5. Make a report to the class, sharing the biographical sketch, the age of the actor in 1832, and the place the actor was at that time. 6. Listen to all the other reports and place all of the actors in their correct locations with their correct ages in 1832. Students - Information 1. The majority of the characters can be found in your public library in biographies and encyclopedia. You will need a library card to access this information. There is enough information about each actor for a biographical sketch. 2. Other actors can be found on the Internet. -

Toward a Sociology of Colonial Subjectivity: Political Agency In

SREXXX10.1177/2332649218799369Sociology of Race and EthnicityHammer and White 799369research-article2018 Original Research Article Sociology of Race and Ethnicity 1 –14 Toward a Sociology of © American Sociological Association 2018 DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/2332649218799369 10.1177/2332649218799369 Colonial Subjectivity: Political sre.sagepub.com Agency in Haiti and Liberia Ricarda Hammer1 and Alexandre I. R. White2 Abstract The authors seek to connect global historical sociology with racial formation theory to examine how antislavery movements fostered novel forms of self-government and justifications for state formation. The cases of Haiti and Liberia demonstrate how enslaved and formerly enslaved actors rethought modern politics at the time, producing novel political subjects in the process. Prior to the existence of these nations, self-determination by black subjects in colonial spaces was impossible, and each sought to carve out that possibility in the face of a transatlantic structure of slavery. This work demonstrates how Haitian and Liberian American founders responded to colonial structures, though in Liberia reproducing them albeit for their own ends. The authors demonstrate the importance of colonial subjectivities to the discernment of racial structures and counter-racist action. They highlight how anticolonial actors challenged global antiblack oppression and how they legitimated their self-governance and freedom on the world stage. Theorizing from colonized subjectivities allows sociology to begin to understand the politics around global racial formations and starts to incorporate histories of black agency into the sociological canon. Keywords colonialism, postcolonial, transnational, racial formation, citizenship The French and American revolutions are seen as and the framers of the Liberian postcolonial state emblematic of political modernity, overthrowing proclaimed their freedom in response to a racial- the authority of the king and colonial overseers. -

Educational Boards and Foundations, 1920-1922

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BUREAU OF EDUCATION BULLETIN, 1922, No. 38 EDUCATIONAL BOARDS AND FOUNDATIONS, 1920-1922 By HENRY R. EVANS EDITORIAL DIVISION. BUREAU OF EDUCATION [Advance sheets from the Biennial Survey of Education 1920-1922] WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFlCE 1922 ADDITIONAL COPIES OF THIS PUBLICATION :MAY BE PROCURED FROH THE SUPERINTENDENT OF DOCUMENTS GOVERNMENT PRJNTING OFFICE WASIDNGTON, D. C. AT 5 CENTS PER COPY EDUCATIONAL BOARDS AND FOUNDATIONS. By HENRY R. EVANS, Editorial Division, Bureau of Education. CoNTENTs.-General Education Board-Rockefeller Foundation-Carnegie Foundation for the Advance ment of Teaching-Jeanes Fund-John F. Slater Fund-Phelps-Stokes Fund. GENERAL EDUCATION BOARD. The General Education Board has, since its foundation in 1902, to July 1, 1921, appropriated $88,125,444.56 for various phases of educn tional work, $80,408,344.99 of this having been paid to or set aside for colleges and other institutions for whites, $5,806,205.62 for insti tutions for negroes, and $1,910,893.95 for miscellaneous objects. The following is a statement of appropriations of the General Education Board for the year ended June 30, 1921 (included in the foregoing paragraph) :1 For whites-Lincoln School, $1,582,929.73; medical schools, $11,- 859,513.25; professors of secondary education, $46,250; rural school agents, $84,700.94; State agents for secondary education, $62,300; universities and colleges, $18,205,353.50; total, $31,841,04 7 .42. For negroes-Colleges and schools, $646,000; county training schools, $128,000; critic teachers, $12,000; expenses of special students at summer schools, $10,000; John F. -

Document Resume Ed 125 949 So 009 226 /Author Title

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 125 949 SO 009 226 /AUTHOR Watson, Rose T. TITLE African Educational Systems: A Comparative Approach. Edu 510. PUB DATE 76 NOTE 45p. -EDRS PRICE 5F-$0.83 HC-$2.06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Bibliographies; Class Activities; *Comparative Education; Course Objectives; *Developing Nations; *Educational Development; *Educational History; Educational Policy; Educational Practice; Educational Trends; *Foundations of Education; Higher Education; Resource Materials; Units of Study {Subject Fields)-; World Problems IDENTIF- RS *Africa ABSTRACT; This course of study for collegestudentsiIl-about e ducational development in tropical Africa, or Africa south of the Sahara, exdluding North Aftica and the Republic' of South Africa.The major goals of the course.-are to help students gain knowledge about the educational policies.nd praCtices of Africai countries underthe rule of Belgium, England, France, .and Portugal during the early20th century and to help students understand contemporary trends,issues, and problems of education anddev)41opm'ent in independent African countries. The course involves students in critiquing, analyzing, and summarizing films, slides, journal articles, bo s, and natio and international documents. Students also write papers,. ile annotated bibliographies on.pertinent topics.. The courseconsists of seven nodules. Each nodule contains anintroduction, a list of student goals, a bibliography of print and nonprintinstructional resources, and suggested student activities andprojects. Included is a pretest with -

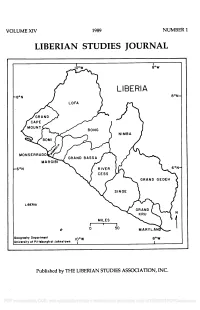

Volume Xiv 1989 Number 1 Liberian Studies Journal -8

VOLUME XIV 1989 NUMBER 1 LIBERIAN STUDIES JOURNAL I 10 °W 8 °W LIBERIA -8 °N 8 °N- MONSERRADO MARGIBI -6°N RIVER 6°N- MILES I I 0 50 MARYLAND Geography Department °W 10 8°W University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown 1 I Published by THE LIBERIAN STUDIES ASSOCIATION, INC. PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor Cover map: compiled by William Kory, cartography work by Jodie Molnar; Geography Department, University of Pittsburgh at Johnstown. PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor VOLUME XIV 1989 NUMBER 1 LIBERIAN STUDIES JOURNAL Editor D. El wood Dunn The University of the South Associate Editor Similih M. Cordor Kennesaw College Book Review Editor Dalvan M. Coger Memphis State University EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD Bertha B. Azango Lawrence B. Breitborde University of Liberia Beloit College Christopher Clapham Warren L. d'Azevedo Lancaster University University of Nevada Reno Joseph S. Guannu Thomas E. Hayden Cuttington University College Africa Faith and Justice Network Svend E. Holsoe J. Gus Liebenow University of Delaware Indiana University Corann Okorodudu Glassboro State College Edited at the Department of Political Science, The University of the South PDF compression, OCR, web optimization using a watermarked evaluation copy of CVISION PDFCompressor CONTENTS THE LIBERIAN REFINERY, A LOOK INSIDE A PARTIALLY "OPEN DOOR" ....................................................... 1 by Garland R. Farmer HARVEY S. FIRESTONE'S LIBERIAN INVESTMENT: 1922 -1932 .. 13 by Arthur J. Knoll LIBERIA AND ISRAEL: THE EVOLUTION OF A RELATIONSHIP 34 by Yekutiel Gershoni THE KRU COAST REVOLT OF 1915 -1916 ........................................... 51 by Jo Sullivan EUROPEAN INTERVENTION IN LIBERIA WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE "CADELL INCIDENT" OF 1908 -1909 .