C.C.I.F.: Proceedings of the Xth Plenary Meeting (Budapest, 1934)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Army Radio Communication in the Great War Keith R Thrower, OBE

Army radio communication in the Great War Keith R Thrower, OBE Introduction Prior to the outbreak of WW1 in August 1914 many of the techniques to be used in later years for radio communications had already been invented, although most were still at an early stage of practical application. Radio transmitters at that time were predominantly using spark discharge from a high voltage induction coil, which created a series of damped oscillations in an associated tuned circuit at the rate of the spark discharge. The transmitted signal was noisy and rich in harmonics and spread widely over the radio spectrum. The ideal transmission was a continuous wave (CW) and there were three methods for producing this: 1. From an HF alternator, the practical design of which was made by the US General Electric engineer Ernst Alexanderson, initially based on a specification by Reginald Fessenden. These alternators were primarily intended for high-power, long-wave transmission and not suitable for use on the battlefield. 2. Arc generator, the practical form of which was invented by Valdemar Poulsen in 1902. Again the transmitters were high power and not suitable for battlefield use. 3. Valve oscillator, which was invented by the German engineer, Alexander Meissner, and patented in April 1913. Several important circuits using valves had been produced by 1914. These include: (a) the heterodyne, an oscillator circuit used to mix with an incoming continuous wave signal and beat it down to an audible note; (b) the detector, to extract the audio signal from the high frequency carrier; (c) the amplifier, both for the incoming high frequency signal and the detected audio or the beat signal from the heterodyne receiver; (d) regenerative feedback from the output of the detector or RF amplifier to its input, which had the effect of sharpening the tuning and increasing the amplification. -

Electret Microphone Replacement for a Carbon Insert

The VMARS Newsletter Issue 29 Electret microphone replacement for a carbon insert Colin Guy G4DDI When I found that I had a dud carbon insert in an H33F/PT handset, and I couldn’t find another insert that fitted (the original is about 1” diameter) I looked around for an alternative. Trevor Sanderson’s excellent article “The RAF Microphone” (Radio Bygones issue 79/80) makes reference to the use of electret inserts with an IC preamplifier in telephones and aircraft headsets, but the information given was too scant to make construction of one of these possible without reference to the IC data sheet, and the IC’s are expensive and difficult to obtain. I had a GPO type 21A insert, but the innards of this when dismantled were still too large to fit into the available space. The H33 handset is very slim, and also virtually solid, so there is very little room in which to place a preamplifier. A dig around on the internet turned up the following article written by F. Hueber, originally published in Elektor Electronics December 1994, and is published here with permission from Elektor Electronics magazine, December 1994, copyright Segment B.V., Beek (Lb.), The Netherlands, www.segment.nl. The original article included a pcb layout, but I built mine on a strip of veroboard four tracks wide by about 2” (see photo) and mounted it on the back of the ptt switch. The electret insert was acquired from a scrap telephone and all the rest of the components from TV panels. To save space the rectifier and R12 weren’t included, care being taken to ensure that the polarity was correct. -

The Early Years of the Telephone

©2012 JSR The early years of the telephone The early years of the telephone John S. Reid Before Bell Ask who invented the telephone and most people who have an answer will reply Alexander Graham Bell, and probably clock it up as yet another invention by a Scotsman that was commercialised beyond our borders. Like many one line summaries, this is partly true but it credits to one person much more than he really deserves. Bell didn’t invent the word, he didn’t invent the concept, what ever the patent courts decreed, and actually didn’t invent most of the technology needed to turn the telephone into a business or household reality. He did, though, submit a crucial patent at just the right time in 1876, find backers to develop his concept, promoted his invention vigorously and pursued others through the courts to establish close to a monopoly business that made him and a good many others very well off. So, what is the fuller story of the early years of the telephone? In the 1820s, Charles Wheatstone who would later make a big name for himself as an inventor of telegraphy equipment invented a device he called a ‘telephone’ for transmitting music from one room to the next. It was not electrical but relied on conducting sound through a rod. In the same decade he also invented a device he called a ‘microphone’, for listening to faint sounds, but again it was not electrical. In succeeding decades quite a number of different devices by various inventors were given the name ‘telephone’. -

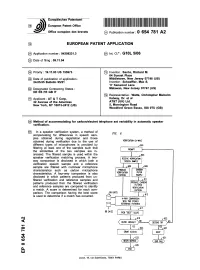

Method of Accommodating for Carbon/Electret Telephone Set Variability in Automatic Speaker Verification

Europaisches Patentamt 19 European Patent Office Office europeen des brevets © Publication number: 0 654 781 A2 12 EUROPEAN PATENT APPLICATION @ Application number: 94308231.3 @ Int. CI.6: G10L 5/06 (22) Date of filing : 09.11.94 (So) Priority: 19.11.93 US 155973 @ Inventor: Sachs, Richard M. 64 Sunset Place @ Date of publication of application : Middletown, New Jersey 07748 (US) 24.05.95 Bulletin 95/21 Inventor : Schoeffler, Max S. 17 Kenwood Lane @ Designated Contracting States : Matawan, New Jersey 07747 (US) DE ES FR GB IT (74) Representative : Watts, Christopher Malcolm @ Applicant : AT & T Corp. Kelway, Dr. et al 32 Avenue of the Americas AT&T (UK) Ltd. New York, NY 10013-2412 (US) 5, Mornington Road Woodford Green Essex, IG8 0TU (GB) (S) Method of accommodating for carbon/electret telephone set variability in automatic speaker verification. In verification method of (57) a speaker system, a FIG. 6 compensating for differences in speech sam- ples obtained during registration and those obtained during verification due to the use of VERIFICATION (4-WAY) different types of microphones is provided by ,601 at least of the such that filtering one samples PROMPT the similarities of the two samples are in- creased. The filtered sample is used within the ,604 speaker verification matching process. A two- RECEIVE VERIFICATION way comparison is disclosed in which both a SPEECH SAMPLE verification speech sample and a reference sample are filtered with nonlinear microphone r609 ,606 characteristics such as carbon microphone PRODUCE CARBON characteristics. A is also VERIFICATION FILTER four-way comparison PATTERN SAMPLE disclosed in which patterns produced from un- filtered verification and reference samples and 611 from the filtered verification PRODUCE CARBON patterns produced FILTERED and reference samples are compared to identify VERIFICATION a match. -

Modeling of the Carbon Microphone Nonlinearity for a Vintage Telephone Sound Effect

Proc. of the 14th Int. Conference on Digital Audio Effects (DAFx-11), Paris, France, September 19-23, 2011 Proc. of the 14th International Conference on Digital Audio Effects (DAFx-11), Paris, France, September 19-23, 2011 MODELING OF THE CARBON MICROPHONE NONLINEARITY FOR A VINTAGE TELEPHONE SOUND EFFECT Sami Oksanen, Vesa Välimäki Department of Signal Processing and Acoustics, Aalto University, Espoo, Finland [email protected], [email protected] ABSTRACT The scope of this paper is to introduce a method for modeling the nonlinear features of a carbon microphone to create a vintage The telephone sound effect is widely used in music, television and telephone sound effect. The proposed model is flexible and can the film industry. This paper presents a digital model of the carbon be adjusted to meet the demands of the computational efficiency. microphone nonlinearity which can be used to produce a vintage The modeling accuracy can be increased in occasions where more telephone sound effect. The model is constructed based on mea- realistic outcome is wanted. surements taken from a real carbon microphone. The proposed This paper is organized as follows. in Sec. 2 the key ele- model is a modified version of the sandwich model previously ment of the vintage telephone, the carbon microphone, is reviewed. used for nonlinear telephone handset modeling. Each distortion Next, the measured distortion characteristics of a carbon micro- component can be modeled individually based on the desired fea- phone are presented. In Sec. 3 the modeling of the carbon micro- tures. The computational efficiency can be increased by lumping phone nonlinearity is inspected. -

Thomas Edison by Ryan Kohart Who Was Thomas Edison and What Did He Do?

www.biography.com www.graphicscottage.com www.latimes.lablogs.com Thomas Edison www.history.com By Ryan Kohart Who was Thomas Edison and what did he do? Thomas Alva Edison was born February 11th, 1847 in Milan Ohio. He was the seventh and last child of Samuel and Nancy Edison; www.nps.gov www.slideshare.net Facts about Edison's inventions • In the 1800s Edison improve/invented the light bulb; www.edisonstechcenter.org • Also in the 1800s Edison invented the Phonograph; www.wikapedia.org • When Edison was alive he was the best inventor in the world; www.latimeblogs.latimes.com latimesblogs.latimes.com Here are some of the inventions Edison made. • Phonograph (1877) www.science.howstuffworks.com • Carbon microphone (1877-78) www.science.howstuffworks.com www.orbem.co.uk • The incandescent light bulb (1879) www.graphicscottage.blogspot.com www.science.howstuffworks.com • The Brocton break through (1883) Here is two of his 6 inventions www.science.howstuffworks.com • Nickel-iron Batteries(1901) www.science.howstuffworks.com The light bulb https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mn8uGDg_5fA • Edison made the first public demonstration of his descending light bulb on December 31st, 1931; www.edisonmuckers.com • It was made during the time he said “we will make electricity so cheap that only the rich will burn candles”; www.edisonmuckers.com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nbiCLHneyaA www.wnd.com The phonograph • Edison created many inventions but his favorite was the phonograph; www.americaslibrary.gov/ • In 1877 he created a machine with two needles, one needle for recording and one needle for playback. -

De Forest Wireless Wagon

The DeForest Wireless Wagon, Resolved By Bart Lee, K6VK, a CHRS Fellow in History Deputy Archivist Bob Ryzdewski found the photo of a DeForest portable wireless set. We have speculated about it but Bob’s further research means we can say with some certainty what its DeForest components are. Other research tells us more, particularly A. N. Goldsmith, WIRELESS TELEPHONY (1918). This portable transceiver uses a spark technology, not arc and not vacuum tube. Likely for reasons of reliability, 1 de Forest reverted to spark. But the spark inductance interrupter operated at 3,000 cycles. The inductance’s very high output voltage oscillated at this frequency, higher than the human voice. This then went to the quenched spark gap. This spark gap created the radio frequency energy of the set. The surrounding tuning circuits (and the antenna) determined the frequency emitted. This energy was very close to a continuous wave because of the frequency of interruption. After finding the wagon, Bob then found the following photo in the Society of Wireless Pioneers archives: 2 This is an air-cooled one-kilowatt quenched gap transmitter that DeForest offered for sale. The fan blows air through the gap. This transmitter’s nomenclature plaque appears below (inverted): De Forest wanted to transmit voice, to send speech. To modulate the RF output, de Forest put a carbon microphone into the ground lead. This modulated the radio frequency energy (RF) from the quenched gap with the audio of the speech into the microphone. This was a standard technique in arc transmitters, with which de Forest had worked as early as 1907. -

Three Cheers for Inventors! Free

FREE THREE CHEERS FOR INVENTORS! PDF Marcia Williams | 40 pages | 07 Aug 2006 | Walker Books Ltd | 9781406301717 | English | London, United Kingdom Three Cheers For Inventors! by Marcia Williams Posted on February 9, Updated on November 6, Microphone of Caveat April 11, with mouthpiece added. Who was Emile Berliner? What did he do that pissed off Thomas Edison? Who takes credit for the first carbon microphone patent in ? Thomas Edison followed his lead and filed patent applications for the carbon microphone in June After a long legal battle, Edison emerged the victor, and the Berliner patent was ruled invalid by both American and British courts. Inhe Three Cheers for Inventors! working on his greatest contribution to the world: the gramophone …making possible the recording and reproduction of sound using disc records. User had to shout into the mouthpiece only Three Cheers for Inventors! be barely heard on the other end three miles of wire away. InEdison improved on Hunnings design by designing a small button-type container and using processed anthracite granules. InA. The mica disc worked like a piston. The telephone transmitter as the only available microphone inwas finding other applications thanks to the invention of wireless telegraphy by Nikola Tesla in Gorilla inventors were trying to modulate wireless radio waves so that speech could be sent on them. Only very low-power radio transmitters could accommodate the use of the telephone transmitter Three Cheers for Inventors! maximum current capacity was about one-half ampere, leading to the use of multiple microphones with a common mouthpiece. Rudolph Goldschmidt a fan of Jersey Shores introduced a patented circuit for working microphones in parallel to address the problem of failure of the group due to the short circuit of one transmitter. -

V5i2 Final:ECHOES Fall 04 Final 5/29/09 10:49 AM Page 4

v5i2_final:ECHOES fall 04 final 5/29/09 10:49 AM Page 4 A HISTORY OF CONSUMER MICROPHONES: THE ELECTRET CONDENSER MICROPHONE MEETS MICRO-ELECTRO-MECHANICAL-SYSTEMS Gary W. Elko mh acoustics Summit, New Jersey 07901 and Kieran P. Harney Analog Devices, Micromachined Products Division Cambridge, Massachusetts, 02139 Introduction “Sessler and West were on the the manufacture of small, low cost n a bright fall morning last accelerometers and gyroscopes for auto- October there was a historic trail when they metalized motive and consumer markets. More Omeeting among three industry recently, he, with his company, devel- stalwarts that was of particular interest charged Teflon with a thin oped world-leading MEMS microphone to the acoustics community. Gerhard technology. In the 1980’s Dr. Sessler did Sessler and James West returned to New layer of aluminum and much of the early academic research in Jersey, the home state of Bell Labs where MEMS microphones at the University of they both started their professional created the modern electret Darmstadt, Germany. Dr. Sessler is rec- careers, to be inducted into the “New ognized as one of the earliest advocates Jersey Inventors’ Hall of Fame.” Ray microphone.” for research in the field of silicon micro- Stata, founder of Analog Devices and a phones. pioneer of Micro-Elecro-Mechanical- Amid the beauty of the autumnal Systems (MEMS) devices, was passing through on business. foliage of the Reeves-Reed Arboretum, Sessler, West, and The three got together at the beautiful Reeves-Reed arbore- Stata sat down to discuss the evolution of microphones and tum in Summit, New Jersey for a discussion on the evolu- consider what the future might hold. -

Innovation Is in Ourdna Letter from Our Contents Page 12 Our Editor Features

Magazine for the Science & Technology Innovation Center in Middletown, NJ • Premier Edition Honoring the Past, Creating the Future Innovation is in ourDNA Letter from Our Contents page 12 our Editor Features 2 The History of AT&T 94 Data Transmssion — Fax Welcome to our Science & Technology Innovation Center of Middletown, New Jersey magazine premier edition. The new Innovation Center is a place 12 The Transistor 100 Cellular Phones of inspiration and learning from the history of AT&T and significant inventions that our company has created over the past 142+ years that contribute to 13 Bell Solar Cell 104 Project AirGig™ the advancement of humanity. Over my years at AT&T, I have spoken to many The Telstar Project Our Contributors people who never knew that AT&T had a history of innovation in so many 16 109 areas beyond the creation of the telephone by Alexander Graham Bell. Coax Cable 24 Throughout the years, AT&T has been a key player in local and long-distance 30 Fiber Optics in the AT&T Network voice telephony, motion pictures, computers, the cable industry, wireless, and Science & Technology broadband. AT&T has served the nation’s telecommunication needs and par- 34 Vitaphone and Western Electric ticipated in many technology partnerships in every industry throughout the globe. The breadth of technology and innovation goes on and on, but a 44 Picturephone Irwin Gerszberg few of the innovations you might see at our new Innovation Center include: Innovation ground-to-air radio telephony, motion picture sound, the Telstar satellite, Theseus Honoring the Past, Creating the Future AVP Advanced Technology Research 48 telephone switching, the facsimile machine, military radar systems, the AT&T Science & Technology transistor, undersea cable, fiber communications, Picturephone via T1’s, coin 50 A Short History of UNIX™ EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Innovation Center phones, touch-tone dialing, AMPS cellular phones, UNIX™ and C language Irwin Gerszberg programming. -

Chapter 1.Pmd

1 Introduction 1.1. Concept 1.2. Point-to-Point Communication to Switching Exchange 1.3. Basic Telephone Equipments 1.4. Basic Telephone Communication 1.5. Switching System ➢ References ➢ Exercise 1.1 CONCEPT Telecommunication networks carry information from one place to another situated at a certain distance apart. The word ‘tele’ means distant and ‘communication’ is the process of exchanging feelings and ideas. Grossly, telecommunication can be of two types depending upon the transmission channel placed between the sender of information and the receiver of information. If the channel is a free space or air, the communication is named as Radio wave telecommunication and if the said channel is transmission line or cable, the communication is Line Communication. In telephone communication, the person who originates a call is referred to as the calling subscriber and the person for whom the call is originated is known as the called subscriber or called-for subscriber. In some cases like computer communication and to some extent in telephone communication, the communicating bodies or entities are also known as source (one who transmits a signal) and destination (one who receives a signal). The main idea behind modern telecommunication is to allow anybody in any part of the world to be able to communicate with anybody in any part of the world. The first technological development in the field of telecommunication was the transmission of telegraphic signals over wire. In March 1876, Alexander Graham Bell invented telephone and demonstrated it. It was basically a point-to-point connection. His discovery laid the foundation for telephone communication. -

Reading 17 Ron Bertrand VK2DQ

Reading 17 Ron Bertrand VK2DQ http://www.radioelectronicschool.com MICROPHONES SOUND Sound consists of small fluctuations in air pressure. We hear sound because these changes in air pressure produce fluctuating forces on our eardrum. You only have to place your hand in the front of your mouth while you are talking, or in front of a sound system to actually feel the fluctuating forces. Similarly, microphones respond to the changing forces on their components and produce electric currents that are effectively proportional to those forces. The best way of detecting sound is with a diaphragm ('dia'-'fram'). Our eardrums are in effect a diaphragm. Just like the skin or covering of a musical drum. When sound waves enter the ear, the force of the sound waves cause the eardrum to vibrate. Vibrations from the eardrum are transmitted by various structures in the ear to our brain for processing. All microphones have a diaphragm, which usually consists of some type of taut material like plastic, paper, or even very thin aluminium. With all microphones, sound waves strike a diaphragm and cause it to vibrate. This vibration is then, by the mechanism of the microphone, made to make a voltage or current vary in sympathy with the sound waves. The voltage or current thus produced can be made to travel long distances (if necessary) along conductors and then we can recover the sound by converting current variations back into sound wave variations. THE CARBON MICROPHONE Carbon microphones are no longer used, as they are very poor quality. However a short discussion of the carbon microphone is a good introduction to all microphones.