Bonds Away: Baseball Mythology and the 2007 Home Run Chase

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Past CB Pitching Coaches of Year

Collegiate Baseball The Voice Of Amateur Baseball Started In 1958 At The Request Of Our Nation’s Baseball Coaches Vol. 62, No. 1 Friday, Jan. 4, 2019 $4.00 Mike Martin Has Seen It All As A Coach Bus driver dies of heart attack Yastrzemski in the ninth for the game winner. Florida State ultimately went 51-12 during the as team bus was traveling on a 1980 season as the Seminoles won 18 of their next 7-lane highway next to ocean in 19 games after those two losses at Miami. San Francisco, plus other tales. Martin led Florida State to 50 or more wins 12 consecutive years to start his head coaching career. By LOU PAVLOVICH, JR. Entering the 2019 season, he has a 1,987-713-4 Editor/Collegiate Baseball overall record. Martin has the best winning percentage among ALLAHASSEE, Fla. — Mike Martin, the active head baseball coaches, sporting a .736 mark winningest head coach in college baseball to go along with 16 trips to the College World Series history, will cap a remarkable 40-year and 39 consecutive regional appearances. T Of the 3,981 baseball games played in FSU coaching career in 2019 at Florida St. University. He only needs 13 more victories to be the first history, Martin has been involved in 3,088 of those college coach in any sport to collect 2,000 wins. in some capacity as a player or coach. What many people don’t realize is that he started He has been on the field or in the dugout for 2,271 his head coaching career with two straight losses at of the Seminoles’ 2,887 all-time victories. -

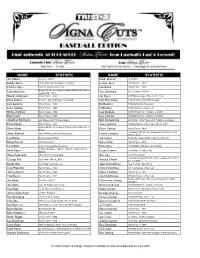

Baseball Classics All-Time All-Star Greats Game Team Roster

BASEBALL CLASSICS® ALL-TIME ALL-STAR GREATS GAME TEAM ROSTER Baseball Classics has carefully analyzed and selected the top 400 Major League Baseball players voted to the All-Star team since it's inception in 1933. Incredibly, a total of 20 Cy Young or MVP winners were not voted to the All-Star team, but Baseball Classics included them in this amazing set for you to play. This rare collection of hand-selected superstars player cards are from the finest All-Star season to battle head-to-head across eras featuring 249 position players and 151 pitchers spanning 1933 to 2018! Enjoy endless hours of next generation MLB board game play managing these legendary ballplayers with color-coded player ratings based on years of time-tested algorithms to ensure they perform as they did in their careers. Enjoy Fast, Easy, & Statistically Accurate Baseball Classics next generation game play! Top 400 MLB All-Time All-Star Greats 1933 to present! Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player Season/Team Player 1933 Cincinnati Reds Chick Hafey 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Mort Cooper 1957 Milwaukee Braves Warren Spahn 1969 New York Mets Cleon Jones 1933 New York Giants Carl Hubbell 1942 St. Louis Cardinals Enos Slaughter 1957 Washington Senators Roy Sievers 1969 Oakland Athletics Reggie Jackson 1933 New York Yankees Babe Ruth 1943 New York Yankees Spud Chandler 1958 Boston Red Sox Jackie Jensen 1969 Pittsburgh Pirates Matty Alou 1933 New York Yankees Tony Lazzeri 1944 Boston Red Sox Bobby Doerr 1958 Chicago Cubs Ernie Banks 1969 San Francisco Giants Willie McCovey 1933 Philadelphia Athletics Jimmie Foxx 1944 St. -

City 'Scapes Online

qjbsS [Free read ebook] City 'Scapes Online [qjbsS.ebook] City 'Scapes Pdf Free Craig Carrozzi audiobook | *ebooks | Download PDF | ePub | DOC Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #3736193 in eBooks 2012-08-10 2012-08-10File Name: B008WV8VNW | File size: 68.Mb Craig Carrozzi : City 'Scapes before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised City 'Scapes: 0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Woulda Coulda ShouldaBy Howlin' CoyoteThe San Francisco Giants had the best record in Major League Baseball in the 1960s--but they failed to win a World Series and won only one National League Pennant after a hectic three game playoff with the Los Angeles Dodgers in 1962. Yet, despite the failures, this was aruguably one of the most exciting teams of that or any era and packed in the fans all over the National League. Hall of Fame stars such as Willie Mays, Willie McCovery, and Orlando Cepeda slammed baseballs off and over fences all over the league. Great pitchers such as Juan Marichal and Gaylord Perry made their mark, Marichal with one of the most unusual pitching motions in baseball history and Gaylord Perry with his infamous spitball.Yet, "City 'Scapes" isn't your usual baseball book, filled with wooden facts and relying on the oft-times predjudiced and spin-oriented pronouncements of former major league players and executives. It is a story--faction if you will--that recreates the excitement of an actual game and era, Giants vs. Cincinnati Reds in 1961, as told through the eyes of a diverse group of fans with loyalties in New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Cincinnati, and who battle by virtue of their opinions as hard as the players on the field while the game is in progress. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Staci Slaughter/Shana Daum April 24, 2003 415-972-1960/972-2496

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT: Staci Slaughter/Shana Daum April 24, 2003 415-972-1960/972-2496 SAN FRANCISCO GIANTS TO DEDICATE GIANTS HISTORY WALK AND STATUE OF HALL-OF-FAMER WILLIE MCCOVEY ON SUNDAY, MAY 4 McCovey Point and China Basin Park Every Giants player, manager and coach to have worn a Giants uniform from 1958 to 1999 will be honored when the San Francisco Giants dedicate McCovey Point and China Basin Park on Sunday, May 4, at 11:30 a.m. The public is invited to attend prior to the Giants vs. Reds game at 2:00 p.m. at Pacific Bell Park. Hall of Famers Juan Marichal, Willie Mays, Willie McCovey and Gaylord Perry will join Giants Manager Felipe Alou and more than 50 Giants alumni (please see the attached list of names) who will participate in the dedication ceremony at China Basin Park. Giants legendary broadcaster Lon Simmons will join current broadcasters Mike Krukow and Duane Kuiper to serve as masters of ceremonies. San Francisco’s newest public park will pay tribute to the San Francisco Giants of the past, especially fan-favorite Willie McCovey. Located along the shores of McCovey Cove between the Lefty O’Doul Bridge, Pier 48 and Terry Francois Boulevard, China Basin Park features grassy picnic areas, Barry Bonds Junior Giants Field, and a promenade with sweeping views of the San Francisco Bay. A nine-foot tall bronze statue of Giants Hall of Famer Willie McCovey will be prominently featured at the northeast portion of the park, which was officially designated as McCovey Point by the San Francisco Port Commission. -

The Baseball Film in Postwar America ALSO by RON BRILEY and from MCFARLAND

The Baseball Film in Postwar America ALSO BY RON BRILEY AND FROM MCFARLAND The Politics of Baseball: Essays on the Pastime and Power at Home and Abroad (2010) Class at Bat, Gender on Deck and Race in the Hole: A Line-up of Essays on Twentieth Century Culture and America’s Game (2003) The Baseball Film in Postwar America A Critical Study, 1948–1962 RON BRILEY McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Jefferson, North Carolina, and London All photographs provided by Photofest. LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Briley, Ron, 1949– The baseball film in postwar America : a critical study, 1948– 1962 / Ron Briley. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7864-6123-3 softcover : 50# alkaline paper 1. Baseball films—United States—History and criticism. I. Title. PN1995.9.B28B75 2011 791.43'6579—dc22 2011004853 BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE © 2011 Ron Briley. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. On the cover: center Jackie Robinson in The Jackie Robinson Story, 1950 (Photofest) Manufactured in the United States of America McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640 www.mcfarlandpub.com Table of Contents Preface 1 Introduction: The Post-World War II Consensus and the Baseball Film Genre 9 1. The Babe Ruth Story (1948) and the Myth of American Innocence 17 2. Taming Rosie the Riveter: Take Me Out to the Ball Game (1949) 33 3. -

Postseaason Sta Rec Ats & Caps & Re S, Li Ecord Ne S Ds

Postseason Recaps, Line Scores, Stats & Records World Champions 1955 World Champions For the Brooklyn Dodgers, the 1955 World Series was not just a chance to win a championship, but an opportunity to avenge five previous World Series failures at the hands of their chief rivals, the New York Yankees. Even with their ace Don Newcombe on the mound, the Dodgers seemed to be doomed from the start, as three Yankee home runs set back Newcombe and the rest of the team in their opening 6-5 loss. Game 2 had the same result, as New York's southpaw Tommy Byrne held Brooklyn to five hits in a 4-2 victory. With the Series heading back to Brooklyn, Johnny Podres was given the start for Game 3. The Dodger lefty stymied the Yankees' offense over the first seven innings by allowing one run on four hits en route to an 8-3 victory. Podres gave the Dodger faithful a hint as to what lay ahead in the series with his complete-game, six-strikeout performance. Game 4 at Ebbets Field turned out to be an all-out slugfest. After falling behind early, 3-1, the Dodgers used the long ball to knot up the series. Future Hall of Famers Roy Campanella and Duke Snider each homered and Gil Hodges collected three of the club’s 14 hits, including a home run in the 8-5 triumph. Snider's third and fourth home runs of the Series provided the support needed for rookie Roger Craig and the Dodgers took Game 5 by a score of 5-3. -

Weekly Notes 072817

MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL WEEKLY NOTES FRIDAY, JULY 28, 2017 BLACKMON WORKING TOWARD HISTORIC SEASON On Sunday afternoon against the Pittsburgh Pirates at Coors Field, Colorado Rockies All-Star outfi elder Charlie Blackmon went 3-for-5 with a pair of runs scored and his 24th home run of the season. With the round-tripper, Blackmon recorded his 57th extra-base hit on the season, which include 20 doubles, 13 triples and his aforementioned 24 home runs. Pacing the Majors in triples, Blackmon trails only his teammate, All-Star Nolan Arenado for the most extra-base hits (60) in the Majors. Blackmon is looking to become the fi rst Major League player to log at least 20 doubles, 20 triples and 20 home runs in a single season since Curtis Granderson (38-23-23) and Jimmy Rollins (38-20-30) both accomplished the feat during the 2007 season. Since 1901, there have only been seven 20-20-20 players, including Granderson, Rollins, Hall of Famers George Brett (1979) and Willie Mays (1957), Jeff Heath (1941), Hall of Famer Jim Bottomley (1928) and Frank Schulte, who did so during his MVP-winning 1911 season. Charlie would become the fi rst Rockies player in franchise history to post such a season. If the season were to end today, Blackmon’s extra-base hit line (20-13-24) has only been replicated by 34 diff erent players in MLB history with Rollins’ 2007 season being the most recent. It is the fi rst stat line of its kind in Rockies franchise history. Hall of Famer Lou Gehrig is the only player in history to post such a line in four seasons (1927-28, 30-31). -

February, 2008

By the Numbers Volume 18, Number 1 The Newsletter of the SABR Statistical Analysis Committee February, 2008 Review Academic Research: The Effect of Steroids on Home Run Power Charlie Pavitt How much more power would a typical slugger gain from the use of performance-enhancing substances? The author reviews a recent academic study that presents estimates. R. G. Tobin, On the potential of a chemical from different assumption about it. Tobin examined the Bonds: Possible effects of steroids on home implications of several, with the stipulation that a batted ball would be considered a home run if it had a height of at least nine run production in baseball, American Journal feet at a distance of 380 feet from its starting point. of Physics, January 2008, Vol. 76 No. 1, pp. 15-20 Computations based on these models results in an increase from about 10 percent of batted balls qualifying as homers, which is This piece is really beyond my competence to do any more than the figure one would expect from a prolific power hitter, to about summarize, but it certainly is timely, and I thought a description 15 percent with the most conservative of the models and 20 would be of interest. Tobin’s interest is in using available data percent for the most liberal. These estimates imply an increase in and models to estimate the increase in home runs per batted ball homer production of 50 to 100 percent. that steroid use might provide. After reviewing past physiological work on the impact of steroids on weightlifters, he Tobin then takes on the impact on pitching, with a ten percent decided to assume an increase in muscle increase in muscle mass leading to a mass of ten percent five percent rise in from its use, leading In this issue pitching speed, to an analogous which is close to increase in kinetic Academic Research: The Effect of Steroids five miles an hour energy of the bat on Home Run Power ...................Charlie Pavitt ....................... -

National Pastime a REVIEW of BASEBALL HISTORY

THE National Pastime A REVIEW OF BASEBALL HISTORY CONTENTS The Chicago Cubs' College of Coaches Richard J. Puerzer ................. 3 Dizzy Dean, Brownie for a Day Ronnie Joyner. .................. .. 18 The '62 Mets Keith Olbermann ................ .. 23 Professional Baseball and Football Brian McKenna. ................ •.. 26 Wallace Goldsmith, Sports Cartoonist '.' . Ed Brackett ..................... .. 33 About the Boston Pilgrims Bill Nowlin. ..................... .. 40 Danny Gardella and the Reserve Clause David Mandell, ,................. .. 41 Bringing Home the Bacon Jacob Pomrenke ................. .. 45 "Why, They'll Bet on a Foul Ball" Warren Corbett. ................. .. 54 Clemente's Entry into Organized Baseball Stew Thornley. ................. 61 The Winning Team Rob Edelman. ................... .. 72 Fascinating Aspects About Detroit Tiger Uniform Numbers Herm Krabbenhoft. .............. .. 77 Crossing Red River: Spring Training in Texas Frank Jackson ................... .. 85 The Windowbreakers: The 1947 Giants Steve Treder. .................... .. 92 Marathon Men: Rube and Cy Go the Distance Dan O'Brien .................... .. 95 I'm a Faster Man Than You Are, Heinie Zim Richard A. Smiley. ............... .. 97 Twilight at Ebbets Field Rory Costello 104 Was Roy Cullenbine a Better Batter than Joe DiMaggio? Walter Dunn Tucker 110 The 1945 All-Star Game Bill Nowlin 111 The First Unknown Soldier Bob Bailey 115 This Is Your Sport on Cocaine Steve Beitler 119 Sound BITES Darryl Brock 123 Death in the Ohio State League Craig -

Printer-Friendly Version (PDF)

NAME STATISTIC NAME STATISTIC Jim Abbott No-Hitter 9/4/93 Ralph Branca 3x All-Star Bobby Abreu 2005 HR Derby Champion; 2x All-Star George Brett Hall of Fame - 1999 Tommie Agee 1966 AL Rookie of the Year Lou Brock Hall of Fame - 1985 Boston #1 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston Minor Lars Anderson Tom Browning Perfect Game 9/16/88 League Off. P.O.Y. Sparky Anderson Hall of Fame - 2000 Jay Bruce 2007 Minor League Player of the Year Elvis Andrus Texas #1 Overall Prospect -shortstop Tom Brunansky 1985 All-Star; 1987 WS Champion Luis Aparicio Hall of Fame - 1984 Bill Buckner 1980 NL Batting Champion Luke Appling Hall of Fame - 1964 Al Bumbry 1973 AL Rookie of the Year Richie Ashburn Hall of Fame - 1995 Lew Burdette 1957 WS MVP; b. 11/22/26 d. 2/6/07 Earl Averill Hall of Fame - 1975 Ken Caminiti 1996 NL MVP; b. 4/21/63 d. 10/10/04 Jonathan Bachanov Los Angeles AL Pitching prospect Bert Campaneris 6x All-Star; 1st to Player all 9 Positions in a Game Ernie Banks Hall of Fame - 1977 Jose Canseco 1986 AL Rookie of the Year; 1988 AL MVP Boston #4 Overall Prospect-Named 2008 Boston MiLB Daniel Bard Steve Carlton Hall of Fame - 1994 P.O.Y. Philadelphia #1 Overall Prospect-Winning Pitcher '08 Jesse Barfield 1986 All-Star and Home Run Leader Carlos Carrasco Futures Game Len Barker Perfect Game 5/15/81 Joe Carter 5x All-Star; Walk-off HR to win the 1993 WS Marty Barrett 1986 ALCS MVP Gary Carter Hall of Fame - 2003 Tim Battle New York AL Outfield prospect Rico Carty 1970 Batting Champion and All-Star 8x WS Champion; 2 Bronze Stars & 2 Purple Hearts Hank -

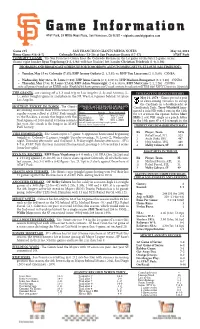

Giants' Record When They

Game #35 SAN FRANCISCO GIANTS MEDIA NOTES May 14, 2012 Home Game #16 (8-7) Colorado Rockies (13-20) at San Francisco Giants (17-17) AT&T Park TONIGHT’S GAME...The San Francisco Giants host the Colorado Rockies in the 1st game of this brief 2-game series... Giants’ right-hander Ryan Vogelsong (1-2, 2.94) will face Rockies’ left-hander Christian Friedrich (1-0, 1.50). PROBABLES AND BROADCAST SCHEDULE FOR TOMORROW AND UPCOMING SET VS. ST. LOUIS (ALL TIMES PDT): • Tuesday, May 15 vs. Colorado (7:15): RHP Jeremy Guthrie (2-1, 5.92) vs. RHP Tim Lincecum (2-3, 5.89) - CSNBA • Wednesday, May 16 vs. St. Louis (7:15): LHP Jaime Garcia (2-2, 4.09) vs. LHP Madison Bumgarner (5-2, 2.80) - CSNBA • Thursday, May 17 vs. St. Louis (12:45): RHP Adam Wainwright (2-4, 6.16) vs. RHP Matt Cain (2-2, 2.28) - CSNBA note: all games broadcast on KNBR radio (English)/68 home games and 2 road contests broadcast on KTRB 860 ESPN Deportes (Spanish) THE GIANTS...are coming off a 3-3 road trip to Los Angeles (1-2) and Arizona (2- THIS DATE IN GIANTS HISTORY 1)...enter tonight’s game in 2nd place in the NL West, 6.0 games behind 1st-place May 14, 1978 - Giants posted a pair Los Angeles. of extra-inning victories to sweep the Cardinals in a doubleheader at HOTTEST TICKET IN TOWN...The Giants LONGEST ACTIVE REGULAR SEASON SELLOUT STREAKS IN MAJORS Candlestick Park...Terry Whitfield ham- are looking to notch their 100th consecutive mered a solo HR with 2 outs in the 12th regular season sellout at AT&T Park tonight Team Streak Date it Started Boston 730* May 15, 2003 for a 5-4 win in the opener, before Marc vs. -

04.23.12 at NYM.Indd

Games #15, #16 SAN FRANCISCO GIANTS MEDIA NOTES April 23, 2012 Road Games #9, #10 (3-5) San Francisco Giants (7-7) at New York Mets (8-6) Citi Field TODAY’S GAMES ...! e San Francisco Giants visit the New York Mets in a doubleheader today to complete this 4 game series...Giants’ right-hander Tim Lincecum (0-2, 10.54) will face Mets’ right-hander Miguel Batista (0-0, 5.40) in Game 1... LHP Madison Bumgarner (2-1, 3.63) will then oppose RHP Dillon Gee (1-1, 2.92) in Game 2. PROBABLES AND BROADCAST SCHEDULE FOR UPCOMING SET AT CINCINNATI (ALL GAME TIMES PDT): • Tuesday, April 24 at Cincinnati (4:10): RHP Mat Latos (0-2, 8.22) vs. RHP Matt Cain (1-0, 1.88) - CSN Bay Area • Wednesday, April 25 at Cincinnati (4:10): RHP Bronson Arroyo (1-0, 2.91) vs. LHP Barry Zito (1-0, 1.71) - CSN Bay Area • ! ursday, April 26 at Cincinnati (9:35): RHP Homer Bailey (1-2, 3.86) vs. RHP Ryan Vogelsong (0-1, 3.38) - CSN Bay Area note: all games broadcast on KNBR radio (English)/68 home games and 2 road contests broadcast on KTRB 860 ESPN Deportes (Spanish) DOUBLE THE FUN ...! e Giants will play a doubleheader today, the club’s 1st since last THIS DATE IN GIANTS HISTORY season when they won both games against the Cubs at Wrigley Field on June 28...this April 23, 1952 -- New York Giants knuck- is the 1st doubleheader that the Giants-Mets face o$ in since April 13, 1997, when the leballer Hoyt Wilhelm hits a home run in Giants won both games here in New York.