Psychoanalysis and the Personality Profiling of Ideological Adversaries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adolf Hitler and the Psychiatrists

Journal of Forensic Science & Criminology Volume 5 | Issue 1 ISSN: 2348-9804 Research Article Open Access Adolf Hitler and the psychiatrists: Psychiatric debate on the German Dictator’s mental state in The Lancet Robert M Kaplan* Clinical Associate Professor, Graduate School of Medicine, University of Wollongong, Australia *Corresponding author: Robert M Kaplan, Clinical Associate Professor, Graduate School of Medicine, University of Wollongong, Australia, E-mail: [email protected] Citation: Robert M Kaplan (2017) Adolf Hitler and the psychiatrists: Psychiatric debate on the German Dictator’s mental state in The Lancet. J Forensic Sci Criminol 5(1): 101. doi: 10.15744/2348-9804.5.101 Received Date: September 23, 2016 Accepted Date: February 25, 2017 Published Date: February 27, 2017 Abstract Adolf Hitler’s sanity was questioned by many, including psychiatrists. Attempts to understand the German dictator’s mental state started with his ascension to power in 1933 and continue up to the present, providing a historiography that is far more revealing about changing trends in medicine than it is about his mental state. This paper looks at the public comments of various psychiatrists on Hitler’s mental state, commencing with his rise to power to 1933 and culminating in defeat and death in 1945. The views of the psychiatrists were based on public information, largely derived from the news and often reflected their own professional bias. The first public comment on Hitler’s mental state by a psychiatrist was by Norwegian psychiatrist Johann Scharffenberg in 1933. Carl Jung made several favourable comments about him before 1939. With the onset of war, the distinguished journal The Lancet ran a review article on Hitler’s mental state with a critical editorial alongside attributed to Aubrey Lewis. -

Durham Research Online

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 23 October 2012 Version of attached le: Published Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Sauerteig, Lutz (2012) 'Loss of innocence : Albert Moll, Sigmund Freud and the invention of childhood sexuality around 1900.', Medical history., 56 (Special issue 2). pp. 156-183. Further information on publisher's website: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/mdh.2011.31 Publisher's copyright statement: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk Med. Hist. (2012), vol. 56(2), pp. 156–183. c The Author 2012. Published by Cambridge University Press 2012 doi:10.1017/mdh.2011.31 Loss of Innocence: Albert Moll, Sigmund Freud and the Invention of Childhood Sexuality Around 1900 LUTZ D.H. SAUERTEIG∗ Centre for the History of Medicine and Disease, Wolfson Research Institute, Queen’s Campus, Durham University, Stockton-on-Tees TS17 6BH, UK Abstract: This paper analyses how, prior to the work of Sigmund Freud, an understanding of infant and childhood sexuality emerged during the nineteenth century. -

Masturbation Practices of Males and Females

Journal of Sex Research ISSN: 0022-4499 (Print) 1559-8519 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/hjsr20 Masturbation practices of males and females Ibtihaj S. Arafat & Wayne L. Cotton To cite this article: Ibtihaj S. Arafat & Wayne L. Cotton (1974) Masturbation practices of males and females, Journal of Sex Research, 10:4, 293-307, DOI: 10.1080/00224497409550863 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/00224497409550863 Published online: 11 Jan 2010. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 549 View related articles Citing articles: 44 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=hjsr20 The Journal of Sex Research Vol. 10, No. 4, pp. 293—307 November, 1974 Masturbation Practices of Males and Females IBTIHAJ S. ARAFAT AND WAYNE L. COTTON Abstract In this study, the authors have examined the masturbation practices of both male and female college students, attempting to test some of the premises long held that men and women differ significantly in such prac- tices. The findings indicate that while there are differences in many of the variables examined, there are others which show striking similarities. Thus, they open to question a number of assumptions held regarding differences in sexual needs and responses of males and females. Introduction The theoretical framework for this study has its basis in the early studies of Kinsey, Pomeroy, and Martin (1948). These first studies sought to document factually and statistically masturbation practices in this country. Though innovative, these studies have become out- dated and limited in light of contemporary developments. -

H MS C70 Morgan, Christiana. Papers, 1925-1974: a Finding Aid

[logo] H MS c70 Morgan, Christiana. Papers, 1925-1974: A Finding Aid. Countway Library of Medicine, Center for the History of Medicine 10 Shattuck Street Boston, MA, [email protected] https://www.countway.harvard.edu/chom (617) 432-2170 Morgan, Christiana. Papers, 1925-1974: A Finding Aid. Table of Contents Summary Information ......................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Series And Subseries Arrangement ................................................................................................................................................... 3 Biography ........................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope And Content Note ................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Collection Inventory ........................................................................................................................................................................... 5 I. Diaries and Notebooks, 1925-1966, 1925-1966 ......................................................................................................................... 5 II. Writings by Christiana Morgan and Henry A. Murray, 1927-1954, 1927-1954 ......................................................................... -

Spring Edition 2020-2021 5 New Ways to Stay Healthy in the Spring By: Ava G

O'Rourke Observer Spring Edition 2020-2021 5 New Ways to Stay Healthy in the Spring By: Ava G. Spring is a new season full of opportunities! As the snow slowly disappears, green grass appears! A new chance arises to get outside and get moving! Here are a few ways to stay healthy this spring. 1. As the weather gets warmer you can take a bike ride around your neighborhood or your house. Regular cycling has many benefits like increased cardiovascular fitness, increased flexibility and muscle strength, joint mobility improvement, stress level decline, posture and coordination improvement, strengthened bones, body fat level decline, disease management or prevention, and finally anxiety and depression reduction. 2. Go for a run. You can run around your house or your neighborhood. There are many health benefits to regular running (or jogging!) Some are improved muscle and bone strength, increased cardiovascular fitness, and it helps to preserve a healthy weight. 3. Go for a hike. Hiking is a great way to enjoy the outdoors and have a great workout at the same time! Hiking can reduce your risk of heart disease, enhance your blood sugar levels and your blood pressure, and it can boost your mood. Here are some great day hikes near Saratoga! You can hike Hadley Mountain, Spruce Mountain, the John Boyd Thacher State Park, Prospect Mountain, Buck Mountain, Shelving Rock Falls & Summit, Cat Mountain, Sleeping Beauty, Thomas Mountain, and Crane Mountain. I have hiked Cat Mountain before, and I loved it! When you reach the summit it has a great view of the ENTIRE Lake George. -

Human Destructiveness and Authority: the Milgram Experiments and the Perpetration of Genocide

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1995 Human Destructiveness and Authority: The Milgram Experiments and the Perpetration of Genocide Steven Lee Lobb College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior Commons, Political Science Commons, and the Social Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Lobb, Steven Lee, "Human Destructiveness and Authority: The Milgram Experiments and the Perpetration of Genocide" (1995). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625988. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-yeze-bv41 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HUMAN DESTRUCTIVENESS AND AUTHORITY: THE MILGRAM EXPERIMENTS AND THE PERPETRATION OF GENOCIDE A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Government The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Steve Lobb 1995 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Steve Lobb Approved, November 1995 L )\•y ^ . Roger Smith .onald Rapi limes Miclot i i TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................................ -

2. We and They

2. We and They Democracy is becoming rather than being. It can easily be lost, but never is fully won. Its essence is eternal struggle. WILLIAM H. HASTIE OVERVIEW Chapter 1 focused on factors that shape an individual’s identity. It also described how those factors are sometimes used to exclude people from membership in various groups. Chapter 2 considers the ways a nation’s identity is defined. That definition has enormous significance. It indicates who holds power in the nation. And it determines who is a part of its “universe of obligation” – the name Helen Fein has given to the circle of individuals and groups “toward whom obligations are owed, to whom rules apply, and whose injuries call for [amends].”1 For much of world history, birth determined who was a part of a group’s “universe of obligation” and who was not. As Jacob Bronowski once explained, “The distinction [between self and other] emerges in prehistory in hunting cultures, where competition for limited numbers of food sources requires a clear demarcation between your group and the other group, and this is transferred to agricultural communities in the development of history. Historically this distinction becomes a comparative category in which one judges how like us, or unlike us, is the other, thus enabling people symbolically to organize and divide up their worlds and structure reality.”2 This chapter explores the power of those classifications and labels. As legal scholar Martha Minow has pointed out, “When we identify one thing as like the others, we are not merely classifying the world; we are investing particular classifications with consequences and positioning ourselves in relation to those meanings. -

The Psychological Correlates of Asymmetric Cerebral Activation As Measured by Electroencephalograph (EEG) Recordings

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library 8-2003 The syP chological Correlates of Asymmetric Cerebral Activation Lisle R. Kingery Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the Cognition and Perception Commons Recommended Citation Kingery, Lisle R., "The sP ychological Correlates of Asymmetric Cerebral Activation" (2003). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 54. http://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/54 This Open-Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. THE PSYCHOLOGICAL CORRELATES OF ASYMMETRIC CEREBRAL ACTIVATION BY Lisle R. Kingery B.A. East Carolina University, 1992 M.A. East Carolina University, 1994 A THESIS Submitted in Partial Fultillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (in Psychology) The Graduate School The University of Maine August, 2003 Advisory Committee: Colin Martindale, Professor of Psychology. Advisor Jonathan Borkum, Adjunct Faculty Marie Hayes, Associate Professor of Psychology Alan M. Rosennasser. Professor of Psychology Geoffrey L. Thorpe, Professor of Psychology Copyright 2003 Lisle R. Kingery All Rights Reserved THE PSYCHOLOGICAL CORRELATES OF ASYMMETRIC CEREBRAL ACTIVATION By Lisle R. Kingery Thesis Advisor: Dr. Colin Martindale An Abstract of the Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements tor the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (in Psychology) August. 2003 This study examined the psychological correlates of asymmetric cerebral activation as measured by electroencephalograph (EEG) recordings. Five content areas were investigated in the context of EEG asymmetry: hierarchical visual processing, creative potential, mood, personality, and EEG asymmetry, and the effect of a mood induction procedure on cognition and EEG asymmetry. -

Aphrodisiacs in the Global History of Medical Thought

Journal of Global History (2021), 16: 1, 24–43 doi:10.1017/S1740022820000108 ARTICLE Aphrodisiacs in the global history of medical thought Alison M. Downham Moore1,2,* and Rashmi Pithavadian3 1School of Humanities and Communication Arts, Western Sydney University, Locked Bag 1797, Penrith NSW 2751, Australia, 2Freiburg Institute for Advanced Study, Albert-Ludwigs-Universität, Albertstraße 19, Freiburg im Breisgau 79100, Germany and 3School of Health Sciences, Western Sydney University, Locked Bag 1797, Penrith NSW 2751, Australia E-mail: [email protected] *Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract The study of aphrodisiacs is an overlooked area of global history which this article seeks to remedy by considering how such substances were commercially traded and how medical knowledge of them was exchanged globally between 1600 and 1920. We show that the concept of ‘aphrodisiacs’ as a new nominal category of pharmacological substances came to be valued and defined in early modern Latin, English, Dutch, Swiss, and French medical sources in relation to concepts transformed from their origin in both the ancient Mediterranean world and in medieval Islamicate medicine. We then consider how the general idea of aphrodisiacs became widely discredited in mid-nineteenth-century scientific medicine until after the First World War in France and in the US, alongside their commercial proliferation in the context of new colonial trade exchanges between Europe, the US, Southeast Asia, Africa, India, and South America. In both examples, we propose that global entanglements played a significant role in both the cohesion and the discreditation of the medical category of aphrodisiacs. -

AMERICAN MASCULINITIES, 1960-1989 by Brad

“HOW TO BE A MAN” AMERICAN MASCULINITIES, 1960-1989 by Brad Congdon Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia March 2015 © Copyright by Brad Congdon, 2015 . To Krista, for everything. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES............................................................................................................vi ABSTRACT......................................................................................................................vii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .............................................................................................viii CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................1 1.1 “MEN” AS THE SUBJECT OF MASCULINITIES...................................5 1.2 “LEADING WITH THE CHIN”: ESQUIRE MAGAZINE AS HEGEMONIC MASCULINITY PROJECT.............................................16 1.3 CHAPTER BREAKDOWN......................................................................25 CHAPTER 2: AN AMERICAN DREAM: MAILER’S GENDER NIGHTMARE............32 2.1 CRISIS! THE ORGANIZATION MAN AND THE WHITE NEGRO....35 2.2 AN AMERICAN DREAM AND HEGEMONIC MASCULINITY ...........43 2.3 AN AMERICAN DREAM AND ESQUIRE MAGAZINE.....……….........54 2.4 CONCLUSION: REVISION AND HOMOPHOBIA...............................74 CHAPTER 3: COOLING IT WITH JAMES BALDWIN............................................... 76 3.1 BALDWIN’S CRITIQUE OF HEGEMONIC MASCULINITY..............80 -

June 2006 Clio’S Psyche Page 1 Clio’S Psyche Understanding the "Why" of Culture, Current Events, History, and Society

June 2006 Clio’s Psyche Page 1 Clio’s Psyche Understanding the "Why" of Culture, Current Events, History, and Society Volume 13 Number 1 June 2006 Fawn M. Brodie Evidential Basis of 25-Year Retrospective Psychohistory Remembering Fawn McKay The Evidential Basis of Brodie (1915-1981) Psychohistory in Group Process Peter Loewenberg John J. Hartman, Ph.D. UCLA University of South Florida I first met Fawn McKay Brodie in 1966 when The application of depth psychology to I invited her for lunch at the urging of Isser Woloch, history—psychohistory—has evolved along three my colleague in French Revolutionary history, who distinct, not always integrated or compatible paths: had the genial idea that we should recruit her to the psychobiography, the history of childhood, and the UCLA History Department. She was smart, dynamics of large group interactive processes. The perceptive about psychoanalysis, honest, in touch purpose of this paper is to take the last approach, with herself, engaging, and delightful. The next year large group process, and review an aspect of the she joined our department as a Lecturer. Fawn empirical, systematic research on small groups, remained a colleague and we nurtured an increasingly which has informed our current understanding of deep friendship for the ensuing 15 years until her psychohistory. It is my contention that small group death in 1981. empirical research may form an empirical evidential (Continued on page 29) (Continued on next page) Freud’s Leadership and Slobodan Milošević and the Viennese Psychoanalysis Reactivation of the Serbian Chosen Trauma Kenneth Fuchsman University of Connecticut Vamık D. Volkan University of Virginia In his recently translated memoirs, Viennese psychoanalyst Isidor Sadger writes: “Freud was not Slobodan Milošević emerged in my mind as merely the father of psychoanalysis, but also its the prototype of a political leader who activates and tyrant!” (Isidor Sadger, Recollecting Freud inflames his large-group’s “chosen trauma” during [Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2005], p. -

Enneagram-Type-2.Pdf

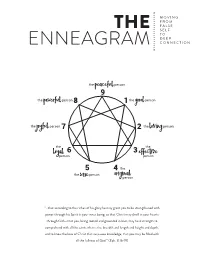

M O V I N G F R O M F A L S E THE S E L F T O D E E P ENNEAGRAM CONNECTION the PEACEFUL person 9 the POWERFUL person 8 1 the GOOD person the JOYFUL person 7 2 the LOVING person the 6 3 the LOYAL person EFFECTIVE person 5 4 the the person WISE ORIGINAL person “…that according to the riches of his glory he may grant you to be strengthened with power through his Spirit in your inner being, so that Christ may dwell in your hearts through faith—that you, being rooted and grounded in love, may have strength to comprehend with all the saints what is the breadth and length and height and depth, and to know the love of Christ that surpasses knowledge, that you may be filled with all the fullness of God.” (Eph. 3:16-19) In the early hours of April 15, 1912, on its maiden voyage from South Hampton to New York City, the Titanic sank when it collided “... THAT ACCORDING TO THE RICHES with an iceberg in the cold waters of the North Atlantic Ocean. OF HIS GLORY HE MAY GRANT Tragically, more than 1,500 people lost their lives. At the time, YOU TO BE STRENGTHENED WITH the Titanic was the largest, most well-built and luxurious ship ever POWER THROUGH HIS SPIRIT IN conceived. It was thought to be unsinkable. As one crew member YOUR INNER BEING ... TO KNOW THE reportedly said, “Not even God himself could sink this ship.” But LOVE OF CHRIST THAT SURPASSES what those aboard the Titanic didn’t know was that hidden beneath KNOWLEDGE ..