IDSA Special Feature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title Items-In-Peace-Keeping Operations - India/Pakistan - Secretary-General's Representative on the Question of Withdrawal of Troops

UN Secretariat Item Scan - Barcode - Record Title Page 34 Date 30/05/2006 Time 9:39:27 AM S-0863-0003-08-00001 Expanded Number S-0863-0003-08-00001 Title items-in-Peace-keeping operations - India/Pakistan - Secretary-General's representative on the question of withdrawal of troops Date Created 24/08/1965 Record Type Archival Item Container S-0863-0003: Peace-Keeping Operations Files of the Secretary-General: U Thant: India/Pakistan Print Name of Person Submit Image Signature of Person Submit UNITED STATIONS Press Services Office of Public Information United Nations, N.Y. (FOR USE OF INFORMATION MEDIA — NOT AH OFFICIAL RECORD) Press Release KASH/131 £4 August 1965 l ' STATEMENT ST.SEE SECTARY-C-MERALON; TEE YJMOWIi SITUATION \ "As already indicated, I am greatly concerned about the situation in Kashmir. It poses a very serious ana dangerous threat to peace. "Therefore, in the course of the past two waeks, I have been in earnest confutation with the peraianent representatives cf the two Governments with a view to stopping the violations o£ the cease-fire line which have been reported to me by General ITimmo, Chief Military Observer of UHMOGIP,* and effecting a restoration of normal conditions along the cease-fire line. "la the same context I have had in mind the possibility of sending urgently a Personal Representative to the area for the purpose of meeting and talking with appropriate authorities of the two Governments and with General Mmmo, and conveying to the Governments my very serious concern about the situation and exploring with them ways and means of preventing any further deterioration in that situation and restoring quiet along the cease-fire line. -

Keesing's World News Archives

Keesing's World News Archives http://www.keesings.com/print/search?SQ_DESIGN_NAME=print&kssp... Keesing's Record of World Events (formerly Keesing's Contemporary Archives), Volume 11, December, 1965 India, Pakistan, Pakistani, Indian, Pakistan, Page 21103 © 1931-2006 Keesing's Worldwide, LLC - All Rights Reserved. The most serious crisis to date in Indo-Pakistani relations, resulting in large-scale fighting between their armed forces, was precipitated when on Aug. 5 armed infiltrators from “Azad Kashmir” (the Pakistani area of Kashmir) began entering Indian Kashmir in an unsuccessful attempt to foment a revolt. In order to prevent further raiders from crossing the cease-fire line, the Indian forces occupied a number of points on the Pakistani side from Aug. 16 onwards. The Pakistan Army launched an offensive into Jammu on Sept. 1, threatening to cut communications between India and Kashmir, whereupon the Indian Army invaded West Pakistan in three sectors during Sept. 6-8. Fighting continued until Sept. 23, when a cease-fire came into force at the demand of the U.N. security Council. While the fighting was in progress the Chinese Government, which had announced its full support for Pakistan, delivered an ultimatum on Sept. 16 threatening war unless India dismantled its fortifications on the Sikkim-Tibet border; the ultimatum was withdrawn on Sept. 22, however. Relations between India and Pakistan remained tense after the cease-fire, as each continued to occupy considerable areas of the other's territory and repeated clashes took place between the two armies. Attempts by the U.N. Secretary-General, U Thant, to negotiate their withdrawal produced no effect, as Pakistan insisted that military disengagement must be accompanied by an attempt to secure a political settlement in Kashmir, this condition being rejected by India. -

DRDO Is Stepping in to Build Ventilators and Manufacture Masks

समाचार पत्र से चियत अंश Newspapers Clippings दैिनक सामियक अिभज्ञता सेवा A Daily Current Awareness Service Vol. 45 No. 67 01 April 2020 रक्षा िवज्ञान पुतकालय Defence Science Library रक्षा वैज्ञािनक सूचना एवं प्रलेखन के द्र Defence Scientific Information & Documentation Centre मैटकॉफ हाऊस, िदली - 110 054 Metcalfe House, Delhi - 110 054 Wed, 01 April 2020 Coronavirus lockdown: Goods trains deliver N95 mask samples for DRDO tests Not taking chances with quality, the defence lab has beesn pressed into service and it has so far received samples from manufacturers in Ludhiana, Delhi and Ambala By Avishek Dastidar New Delhi: The DRDO laboratory in Gwalior is testing N95 masks after receiving samples from bulk manufacturers via goods train drivers as the country prepares to mass-produce protective gear for medical staff on the frontlines of the COVID-19 outbreak. As per government estimates, 2.4 crore N95 masks will be needed up to June amid rising infections and this vital transportation has come through a collaboration between Indian Railways and the Textiles Ministry. Not taking chances with quality, the defence lab has beesn pressed into service and it has so far received samples from manufacturers in Ludhiana, Delhi and Ambala. “No one wants to take any chances with the quality. So we had been given standards, based on which we have made the prototype and now they have been sent for testing. We are awaiting results,” said Ashwani Garg of Pious Textiles in Ludhiana, which can produce around 3,000 masks per day. -

SECONDARY STAGE ENGLISH Sindh Textbook Board, Jamshoro

English Sindh Text Book Board, Jamshoro. SECONDARY STAGE ENGLISH BOOK ONE FOR CLASS IX For Sindh Textbook Board, Jamshoro. 1 English Sindh Text Book Board, Jamshoro. CONTENTS Page 1. The Last Sermon of the Holy Prophet 3 2. Shah Abdul Latif 7 3. The Neem Tree (Poem) 17 4. Moen-jo-Daro 19 5. Helen Keller 28 6. The Daffodils (Poem) 7. Allama lqbal 37 8. The Role of Women in the Pakistan Movement 45 9. Children (Poem) 55 10. What the Quaid-i-Azam Said 59 11. Health is Wealth 66 12. Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening (Poem) 71 13. The Great War Hero 74 14. Nursing 80 15. The Miller of the Dee (Poem) 85 16. Responsibilities of a Good Citizen 87 17. The Village Life in Pakistan 92 18. Abou Ben Adhem (Poem) 97 19. The Secret of Success 99 20. The Guddu Barrage 106 2 English Sindh Text Book Board, Jamshoro. 1. THE LAST SERMON OF THE HOLY PROPHET (Peace be upon him) Hazrat Muhammad (peace be upon him) the Prophet of Islam, was born in 571* A.D. at Makkah. He belonged to the noble family of Quraish. Our Holy Prophet Muhammad (Peace be upon him) is the last of the prophets. The Quraish used to worship idols and did not believe in One God. Hazrat Muhammad (peace be upon him) asked the Quraish not to worship their false gods. He told them that he was Prophet of God and asked them to worship the One and the only true God. Most of them refused to accept Islam. -

“Strategic Restraint” Revisited: the Case of the 1965 India-Pakistan War

India Review ISSN: 1473-6489 (Print) 1557-3036 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/find20 Indian “Strategic Restraint” Revisited: The Case of the 1965 India-Pakistan War Rudra Chaudhuri To cite this article: Rudra Chaudhuri (2018) Indian “Strategic Restraint” Revisited: The Case of the 1965 India-Pakistan War, India Review, 17:1, 55-75, DOI: 10.1080/14736489.2018.1415277 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/14736489.2018.1415277 Published online: 29 Mar 2018. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 313 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=find20 INDIA REVIEW 2018, VOL. 17, NO. 1, 55–75 https://doi.org/10.1080/14736489.2018.1415277 Indian “Strategic Restraint” Revisited: The Case of the 1965 India-Pakistan War Rudra Chaudhuri ABSTRACT Political scientists and analysts have long argued that Indian strategic restraint is informed primarily by Indian political lea- ders’ aversion to the use of force. For some scholars, India’s apparent fixation with restraint can be traced to the very foundation of the modern Indian state. This article contests what it considers to be a reductionist position on strategic restraint. Instead, it argues that Indian strategic restraint has in fact been shaped more by structural issues such as the limited availability of logistics and capabilities, the impact of domestic political contest, the effect of international attention to a crisis and the need for international legitimacy, and the political, economic, and military cost-benefit analysis asso- ciated with the use of force and the potential for escalation. -

List of NFC Enabled

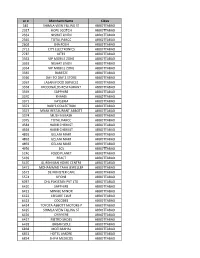

sn # Merchant Name Cities 582 SHIMLA VIEW FILLING ST ABBOTTABAD 2327 HOPE SCOTCH ABBOTTABAD 2362 NISHAT LINEN ABBOTTABAD 2365 TOTAL PARCO ABBOTTABAD 2602 SHA POSH ABBOTTABAD 2713 CITY ELECTRONICS ABBOTTABAD 2787 KITES ABBOTTABAD 3362 VIP MOBILE ZONE ABBOTTABAD 3363 NISHAT LINEN ABBOTTABAD 3364 VIP MOBILE ZONE ABBOTTABAD 3365 BAREEZE ABBOTTABAD 3366 DAY TO DAY 2 STORE ABBOTTABAD 3367 LASANI FOOD SERVICES ABBOTTABAD 3368 MCDONALDS RESTAURANT ABBOTTABAD 3369 SAPPHIRE ABBOTTABAD 3370 KHAADI ABBOTTABAD 3371 KAYSERIA ABBOTTABAD 3372 RABI'S COLLECTION ABBOTTABAD 3373 MNAK RESTAURANT ABBOTT ABBOTTABAD 3374 MUSH N MASH ABBOTTABAD 3375 TOTAL PARCO ABBOTTABAD 4584 HABIB CHEMIST ABBOTTABAD 4664 HABIB CHEMIST ABBOTTABAD 4891 GELANI MART ABBOTTABAD 4892 GELANI MART ABBOTTABAD 4893 GELANI MART ABBOTTABAD 4956 ECS ABBOTTABAD 5240 FOOD PLANET ABBOTTABAD 5469 REACT ABBOTTABAD 5470 AL REHMAN HOME CENTRE ABBOTTABAD 5471 MOHAMMAD TAHA JEWELLER ABBOTTABAD 5573 DE MINISTER CAFE ABBOTTABAD 5574 UFONE ABBOTTABAD 6037 DHL PAKISTAN PVT LTD ABBOTTABAD 6420 SAPPHIRE ABBOTTABAD 6421 MINNIE MINOR ABBOTTABAD 6422 LEISURE CLUB ABBOTTABAD 6423 COCOBEE ABBOTTABAD 6424 TOYOTA ABBOTT MOTORS P ABBOTTABAD 6425 SHIMLA VIEW FILLING ST ABBOTTABAD 6426 CHINYERE ABBOTTABAD 6427 METRO SHOES ABBOTTABAD 6428 URBAN SOLE ABBOTTABAD 6838 MOTI MAHAL ABBOTTABAD 6851 HOTEL AMORE ABBOTTABAD 6854 SHIFA MEDICOS ABBOTTABAD 6856 KHYBER MEDICOSE ABBOTTABAD 6857 SHAHEEN CHEMIST ABBOTTABAD 6858 SHAHEEN CHEMIST ABBOTTABAD 6861 USMAN PAINT HOUSE ABBOTTABAD 6975 SAVE MART ABBOTTABAD 6976 SAVE MART -

In the Line of Fire

IN THE LINE OF FIRE A Memoir According to Time magazine, Pakistan's President Pervez Musharraf holds 'the world's most dangerous job: He has twice come within inches of assassination. His forces have caught over 670 members of Al Qaeda, yet many others remain at large and active, including Osama bin Laden and Ayman A1 Zawahiri. Long locked in a deadly embrace with its nuclear neighbour India, Pakistan has twice come close to full-scale war since it first exploded a nuclear bomb in 1998. As President Musharraf struggles for the security and political future of his nation, the stakes could not be higher for the world at large. It is unprecedented for a sitting head of state to write a memoir as revelatory, detailed and gripping as In the Line 0f Fire.Here, for the first time, readers can get a 1st- hand view of the war on tenor in its central theatre. President Musharraf details the manhunts for Bin Laden and Zawahiri, and their top lieutenants, complete with harrowing cat-and-mouse games, informants, interceptions, and bloody firefights. He tells the stories of the near- miss assassination attempts not only against himself, but against Shaukut Aziz (later elected Prime Minister) and one of his top army officers, and the fatal abduction and beheading of the US journalist Daniel Pearl -as well as the investigations that uncovered the perpetrators. He details the army's mountain operations that have swept several valleys clean, and he talks about the areas of North Waziristan where Al Qaeda is stiil operating. Yet the war on terror is just one of the many headline- making subjects in I%the Linc flit. -

1965 UN Yearbook

164 POLITICAL AND SECURITY QUESTIONS ster of Pakistan accused India of having action had been announced in the Indian mounted a treacherous armed attack and stated Parliament and publicized in the Indian press. that Pakistan would exercise its inherent right When, after exercising restraint for two weeks, of self-defence until the Security Council had Pakistan had been forced to take defensive taken effective measures to restore peace and action in the Chhamb area of Kashmir, India security. had been the first to throw aircraft into combat During the Council's meeting of 6 September and thus make another move towards escala- the representative of Pakistan said that India's tion of the conflict. invasion of Pakistan was an event without The representative of Pakistan observed that parallel in the history of the United Nations. the foregoing events had now been over- It was not only a brazen aggression on the shadowed by the attack on Pakistan territory territory of a Member State but also a de- that the Indian army had just launched across liberate transgression of the very purposes and the international frontier on the Lahore front. principles of the United Nations. India's pre- The pretexts India was using to justify that sent attack on Pakistan had come as the culmi- attack were entirely false. It was in fact an nation of a series of planned, provocative acts, act of naked aggression consistent with the he continued. Although the Foreign Minister attitude India had maintained in the Kashmir of Pakistan, in response to the Security Coun- -

Parvez Hasan 923.5 Parvez Hasan My Life and My Country: Memoirs of a Pakistani Economist / Parvez Hasan.-Lahore: Sang-E-Meel Publications, 2010

MY LIFE AND MY COUNTRY Memoirs of a Pakistani Economist Parvez Hasan 923.5 Parvez Hasan My Life and My Country: Memoirs of a Pakistani Economist / Parvez Hasan.-Lahore: Sang-e-Meel Publications, 2010. 549pp. 1. Autobiography. I. Title. 2010 Published by: Niaz Ahmad Sang-e-Meel Publications, Lahore. ISBN-10: 9 6 9 - 3 5 - 0 0 0 0 - 0 ISBN-13: 978-969-35-0000-0 Sang-e-Meel Publications 25 Shahrah-e-Pakistan (Lower Mall), Lahore-54000 PAKISTAN Phones: 37220100-37228143 Fax: 37245101 http://www.sang-e-meel.com e-mail: [email protected] PRINTED AT: HAJI HANIF & SONS PRINTERS, LAHORE. 3 My Life and MY Country Memoirs of a Pakistani Economist 4 MY LIFE AND MY COUNTRY CONTENTS 5 Contents Introduction Chapter 1 A Punjabi Childhood Chapter 2 Government College, Partition, and Pakistan’s Emergence Chapter 3 Early Years of Pakistan Chapter 4 Becoming a Professional Economist Chapter 5 Year in Washington D.C.: 1954–55 Chapter 6 State Bank of Pakistan Years: 1955–1958 Chapter7 Yale University: 1958–1960 Chapter 8 Pakistan Interlude: 1960–1961 Chapter 9 Life and Times in Saudi Arabia: 1961–1965 Chapter 10 Remembering Anwar Ali: An Unsung Pakistan Hero Chapter 11 Heydays of Planning in Pakistan: 1965-70 Chapter 12 Crumbling of Ayub Regime and General Yahya’s Takeover Chapter 13 An Unexpected Job Offer from the World Bank and Goodbye to Lahore Chapter 14 Remembering Early Washington Years and Breakup of Pakistan Chapter 15 World Bank 1970–1996 6 MY LIFE AND MY COUNTRY Chapter 16 Philippines--- The Asian Lagga Chapter 17 Economic and Social Transformation -

Chapter13.Pdf

13 THE BLUNTED SCIMITAR The Navy's Trammels and Compulsions During the 1965 Indo-Pak War Much has been written on Indo-Pak relations since the two countries attained Independence in 1947. In a very recent volume titled India and Pakistan - Crisis of Relationship', edited by Air Commandore Jasjit Singh, Director, Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, he writes in his introduction 'If a single most dominant characteristic of the relations between Pakistan and India since 1947 was to be identified then the finger would almost involuntarily point to the mistrust and lack of confidence between the two sovereign states, both highly sensitive to their separate-ness and sovereignty as young modem nation states burdened by a deeply shared, historically long continuity of civilizational and cultural bonds. Although the manifestation of this in the shape of animosities is not necessarily shared by the peoples of the two countries, many attitudes and perceptions among them have been shaped by this crisis of relationship at the state-to-state level. This factor has been central to the growth and sustenance of antagonisms. The degree and form of crisis in the relationship -and the rhetoric that goes with it - has varied with time, events and personalities; but the substance of it has remained.' He, further, verypertinently observes, The emotional upsurge which helped to establish the nation state (Pakistan) could not be translated or transformed into a durable political system to govern it. The fragility of the political institutions increased with the passage of time. This in turn generated and sustained the third factor-the rise of the praetorian state in which the military, the bureaucracy and the feudal lords (of land and business) progressively acquired a dominant control over the state structure. -

Hattrlffbtpr Fcumittg W M a Pakistani, Indians Bombing Each Other's

f Avsrtn Ddibr Nst Pr«M Ron TIm WMtiMr fw ttM Wesk Bndsd rnrsnos8 of 0 . •- Waathot ■sptsmhsr d» 19SS 1 3 , 8 9 3 HattrlfFBtpr fcumittg w m a nor, soot tsnigM Lsw IS 8s SB. Fair U sa om m . High M Is S^ Msmber of ttio Andtt ' Borssa of Cironlstlon Maneheeter^A City of VIttage Charm a (OtoMlltod AiwrtUbtg «M T a f M) PRICE SEVEN CBNtB VOL. LXXXIV, NO. 287 (TWENTY-FOUR PAGBft-TWO SECTIONS) MANCHESTER, CONN., TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 7, 1965 News of Schools School opens this w s ^ and today’s Herald con Slams tains a special five-page Pakistani, Indians Bombing school section on pages 17 through 21. Besides Man chester, there will be school opening news for Bolton, Andover, Vernon, South Windsor, Hebron Nassau Coventry, Columbia, and Tolland. Each Other’s Major Cities MIAMI, Pla. (AP) _^^storm forecaster at Miami. “ We must be reconciled to a pro Hurricane Betsy sat longed period of warnings and astride Nassau today, giv threats. Betsy may be around NEW DELHI, Ind-ls ing the world-famed resort for several days." NYC Schools (A P )—^Indian and Pakis Dunn said latest reports Indl-1 tani .bombers struck at s i t city a terrible beating with cated that the calm center of| 186 - mile • an - hour winds the eye did not pass over Nm - Face Strike 4$wSS5sS8s5isSS58SB^S8^ large cities in both coun and massive tides, and sau'; giving the city that brief tries today, spreading ths southern Florida was respite. conflict 1,000 miles across ^ H ‘•■V - Instead, he said, the eye evi By Teachers the subcontinent to East warned that it might be in dently passed Just off the Island : ^ ^ I for days of anxiety. -

Their Language of Love

Bapsi Sidhwa T H E I R L A N G U A G E O F L O V E Contents Dedication A Gentlemanly War Breaking It Up Ruth and the Hijackers Ruth and the Afghan The Trouble-Easers Their Language of Love Sehra-bai Defend Yourself Against Me Acknowledgements Follow Penguin Copyright Page For my son Khodadad Kermani (Koko) and the childhood years lost to us both A Gentlemanly War It was 1965, and Pakistan and India were at war. The bone of contention was, as always, Kashmir. The Pakistan army—one seventh the size of the Indian army and beleaguered on more fronts than it could handle—had concentrated on the Kashmir and Sialkot fronts. Within a day of the onset of the war it was rumoured that the Indian forces had crossed the border into Pakistan at Wagah, only sixteen miles from Lahore. The Indian army had, in fact, advanced to a wide canal inside the border so easily that they had come smack-up against a psychological barrier: they did not believe that Lahore was left virtually unprotected. Certain that a cleverly camouflaged trap was waiting to be sprung—and calculating that a strategic retreat would be disastrously slowed by the narrow bridge across the canal—the Indians had brought their infantry, three-tonners and tanks to a precipitate halt. The rumour of the Indian army’s advance percolated with so much insistence that we guessed it was at least partially true. We were confident though that Lahore, a thriving metropolis of eight million, would never be left unprotected.