Download Full Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rapport De Synthèse Sur Le Pluralisme

Royaume du Maroc Rapport Semestriel sur le Pluralisme dans les Médias Audiovisuels (Magazines d’information) Du 1er Janvier au 30 Juin 2010 Sommaire Préface 004 I – Règles de référence 006 1- Médias audiovisuels objet du contrôle 007 2- Modalités de relevé dans les médias audiovisuels à programmation nationale 007 3- Modalités de relevé dans les médias audiovisuels à programmation régionale et locale 008 II – Présentation des résultats globaux 010 Graphes globaux des Quatre Parts sur les médias audiovisuels suivis 011 III – Observations générales 015 IV – Résultats par catégorie de médias 020 1 - Médias audiovisuels publics 021 . TV Al Oula 021 . TV 2M 033 . TV Tamazight 029 . TV Laâyoune 039 . Radio Nationale 044 . Radio Amazighe 050 . Radio Chaîne Inter 056 Observations relatives aux médias audiovisuels publics 066 2 - Médias audiovisuels privés à programmation nationale 068 . Radio Aswat 069 . Radio Med 075 . Radio Chada FM 081 . Radio Atlantic 087 . Radio Luxe 093 Observations relatives aux médias audiovisuels privés à programmation 103 nationale 3 - Médias audiovisuels privés à programmation régionale 105 . Radio Casa FM (programmes nationaux) 106 . Radio Casa FM (programmes régionaux) 112 . Radio MFM Atlas (programmes régionaux) 119 2 . Radio MFM Saïss (programmes régionaux) 121 . Radio MFM Souss (programmes régionaux) 126 . Cap Radio 131 Observations sur les médias audiovisuels privés régionaux 137 4 - Médias audiovisuels privés à programmation locale 139 . Radio Plus Agadir 140 . Radio Plus Marrakech 146 Observations sur les médias audiovisuels privés locaux 151 V – Annexes, Sommaire & Tableaux 153 3 Préface En vertu du Dahir l’ayant instituée, et du fait de l’évolution accélérée du secteur audiovisuel, la Haute Autorité de la Communication Audiovisuelle (HACA) a été appelée à mettre en place un cadre normatif précis pour la gestion du pluralisme politique dans les médias audiovisuels afin de mieux garantir la liberté d’expression des organisations politiques, syndicales, professionnelles et associatives. -

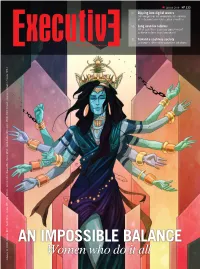

An Impossible Balance

March 2019 No 233 12 | Dipping into digital waters Convergences of awareness on several of Lebanon’s overdue cyber priorities 16 | Long overdue reforms What can the Lebanese government achieve in less than two years? 42 | Toward a cashless society Lebanon’s alternative payment solutions www.executive-magazine.com AN IMPOSSIBLE BALANCE Women who do it all Lebanon: LL 10,000 - Bahrain: BD2 - Egypt: EP20 - Jordan: JD5 - Iraq: ID6000 - Kuwait: KD2 - Oman: OR2 - Qatar: QR20 - Saudi Arabia: SR20 - Syria: SP200 - UAE: Drhm20 - Morocco: Drhm30 - Tunisia: TD5.5 - Tunisia: Drhm30 - Morocco: Drhm20 - UAE: SP200 - Syria: SR20 Arabia: - Qatar: - Saudi OR2 QR20 KD2 - Oman: ID6000 - Kuwait: JD5 - Iraq: LL 10,000 - Bahrain: - Egypt: BD2 EP20 - Jordan: Lebanon: 12 executive-magazine.com March 2019 EDITORIAL #233 Dismantling privilege A friend of mine, an ex-minister, once told me, “The Lebanese system works perfectly, like clockwork—but in all the wrong ways.” The money pledged by the international community at CEDRE requires long overdue structural reforms on our part. Take the deficit caused through subsidizing the failing public utility Electricité du Liban (EDL). To actually fix EDL would require our politicians to dismantle a parallel industry of which they are the benefactors. The corruption that keeps sectors like telecommunications and electricity profitable for our elite is entirely of their own making; and only through self-inflicted wounds would they be able to reform these sectors for the benefit of all Lebanese. The frequent foreign delegations who come to Lebanon surely laugh as they come out of another pointless high-level meeting, knowing that the problems they have raised were caused by these politicians, and the reforms that are so desperately needed have been blocked by these same men—and it has been men—for decades. -

Marokkos Neue Regierung: Premierminister Abbas El Fassi Startet Mit Einem Deutlich Jüngeren Und Weiblicheren Kabinett

Marokkos neue Regierung: Premierminister Abbas El Fassi startet mit einem deutlich jüngeren und weiblicheren Kabinett Hajo Lanz, Büro Marokko • Die Regierungsbildung in Marokko gestaltete sich schwieriger als zunächst erwartet • Durch das Ausscheiden des Mouvement Populaire aus der früheren Koalition verfügt der Premierminister über keine stabile Mehrheit • Die USFP wird wiederum der Regierung angehören • Das neue Kabinett ist das vermutlich jüngste, in jedem Fall aber weiblichste in der Geschichte des Landes Am 15. Oktober 2007 wurde die neue ma- Was fehlte, war eigentlich nur noch die rokkanische Regierung durch König Mo- Verständigung darauf, wie diese „Re- hamed VI. vereidigt. Zuvor hatten sich die Justierung“ der Regierungszusammenset- Verhandlungen des am 19. September vom zung konkret aussehen sollte. Und genau König ernannten und mit der Regierungs- da gingen die einzelnen Auffassungen doch bildung beauftragten Premierministers Ab- weit auseinander bzw. aneinander vorbei. bas El Fassi als weitaus schwieriger und zä- her gestaltet, als dies zunächst zu erwarten Für den größten Gewinner der Wahlen vom gewesen war. Denn die Grundvorausset- 7. September, Premierminister El Fassi und zungen sind alles andere als schlecht gewe- seiner Istiqlal, stand nie außer Zweifel, die sen: Die Protagonisten und maßgeblichen Zusammenarbeit mit dem größten Wahlver- Träger der letzten Koalitionsregierung (Istiq- lierer, der sozialistischen USFP unter Füh- lal, USFP, PPS, RNI, MP) waren sich einig rung von Mohamed Elyazghi, fortführen zu darüber, die gemeinsame Arbeit, wenn wollen. Nur die USFP selbst war sich da in auch unter neuer Führung und eventuell nicht so einig: Während die Basis den Weg neuer Gewichtung der Portfolios, fortfüh- die Opposition („Diktat der Urne“) präfe- ren zu wollen. -

L'équipementier Américain Adient S'implante À Kénitra

Directeur fondateur : Ali Yata | Directeur de la publication : Mahtat Rakas L’inscription sur les listes électorale Votre opportunité pour le changement Si vous êtes âgés de 18 ans ou plus, vous pouvez visiter le site électronique suivant : www.listeselectorales.ma Pour vous rassurer que vous êtes inscrits sur les listes Si vous n’êtes pas inscrits, vous pouvez le faire en rem- Mercredi 16 décembre 2020 N°13900 Prix : 4 DH - 1 Euro plissant le formulaire ou de le faire directement dans les bureaux d’inscription ouverts. Automobile Les listes électorales sont ouvertes jusqu’au L’équipementier américain 31 décembre 2020 Adient s’implante à Kénitra SM le Roi souhaite prompt rétablissement équipementier automobile américain au président algérien Adient compte investir 15,5 millions Sa Majesté le Roi Mohammed VI a adressé un message L' d'euros (M€) pour mettre en place au président de la République algérienne démocratique une nouvelle unité de production de coiffes à la et populaire, Abdelmadjid Tebboune, dans lequel le Zone d'accélération industrielle à Kénitra et ce, Souverain lui souhaite prompt rétablissement. suite à un protocole d'accord signé, lundi à « Votre allocution à l’adresse du peuple algérien frère Rabat, avec le ministère de l'Industrie, du com- dimanche a montré, Dieu soit loué, votre rétablisse- merce et de l'économie verte et numérique. ment », écrit SM le Roi dans ce message. En vertu de ce protocole d'accord, paraphé par le Le Souverain exprime Sa profonde satisfaction suite à ministre de l'Industrie, du commerce et de l’éco- l’amélioration de l’état de santé du président algérien, nomie verte et numérique, Moulay Hafid implorant le Très-Haut de lui accorder un rétablisse- Elalamy, et le vice-président Exécutif EMEA du ment rapide et complet, santé et longue vie. -

Morocco: the Monarch and Rumours Morocco: the Monarch and Rumours 33

32 Morocco: the Monarch and Rumours Morocco: the Monarch and Rumours 33 of the wife of Mohammed VI. This was one of in the salons. Prior to this dispatch, there had the first to be written about Princess Salma, never been – to my knowledge – articles in the Morocco: the Monarch and Rumours the king’s wife. Here the Royal Family reacted Moroccan press on the King’s health. swiftly, and a missive, in a menacing tone, Maria Moukrim, a journalist at the time for landed on the editorial desk of the newspaper. the weekly al-Ayam, was following the story, Freelance journalist Ali Amar reflects on the ‘The communiqué was an event. The news story incident: ‘This unprecedented state of fever was at first a rumour that had been doing the pitch illustrates the distance the monarchy rounds for some time’, she remembers. In order Salaheddine Lemaizi wishes to maintain with the kingdom’s media to establish the truth, journalists published on the subject of the princess, even if the throne false information on the subject. Quoting an does not hesitate in ostentatiously exposing unnamed medical source, the daily al-jarida itself in foreign magazines. Its marketing- al-Oula published an article proposing a savvy approach beyond its borders contrasts noticeably different explanation, stating that with the sacredness of the King for Moroccan ‘the origin of the rotavirus contracted by the subjects who remain infantilised by the law.’6 King is due to his use of corticosteroids against He adds: “The Palace seeks a one-way means of asthma that cause swelling in the body and communication.”7 decreased immunity.’ The weekly al-Michaal In the Moroccan political system, the then published an article whose headline In comparison with the majority of Middle this obscurantism been lifted since the arrival of King is by far the predominant actor. -

The Monthly-March 2012 English

issue number 116 |March 2012 WAGE HIKE LEBANON AIRPORTS “the monthLy” interviews: RITA MAALOUF www.iimonthly.com • Published by Information International sal RENT ACT TWELVE EXTENSIONS AND A NEW LAW IS YET TO MATERIALIZE Lebanon 5,000LL | Saudi Arabia 15SR | UAE 15DHR | Jordan 2JD| Syria 75SYP | Iraq 3,500IQD | Kuwait 1.5KD | Qatar 15QR | Bahrain 2BD | Oman 2OR | Yemen 15YRI | Egypt 10EP | Europe 5Euros March INDEX 2012 4 RENT ACT 7 GLC AND BUSINESS OWNERS LOCK HORNS WITH NAHAS OVER WAGE HIKE 10 ElECTIONS 2013 (2) 12 WILL LEBANON OPERATE FOUR AIRPORTS OR ONLY ONE? 14 IDAL 16 THOUSANDS OF MOBILE PHONE LINES AT THE DISPOSAL OF SECURITY FORCES P: 21 P: 4 17 REOPENING OF BEIRUT Pine’s FOREST 18 VITAMINS & SUPPLEMENTS: DR. HANNA SAADAH 19 PSYCHOLOGICAL EFFECTS OF IMPOTENCE ON MEN IN THE MIDDLE EAST: MICHEL NAWFAL 20 ALF, BA, TA...: DR. SAMAR ZEBIAN 21 INTERVIEW: RITA MAALOUF P: 12 23 TORTURE - IRIDESCENCE 24 NOBEL PRIZES IN PHYSICS (2) 39 Mansourieh’s HIGH-VOLTAGE POWER 28 THE SOCIAL AND CULTURAL DEVELOPMENT LINES ASSOCIATION (INMA) 40 JANUARY 2012 TIMELINE 30 HOW TO BECOME A CLERGYMAN IN YOUR RELIGION? 43 EgYPTIAN ELECTIONS 31 POPULAR CULTURE 47 REAL ESTATE PRICES IN LEBANON - 32 DEBUNKING MYTH #55: DREAMS JANUARY 2012 33 MUST-READ BOOKS: CORRUPTION 48 FOOD PRICES - JANUARY 2012 34 MUST-READ CHILdren’s bOOK: CAMELLIA 50 VENOMOUS SNAKEBITES 35 LEBANON FAMILIES: HAWI FAMILIES 50 BEIRUT RAFIC HARIRI INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT - JANUARY 2012 36 DISCOVER LEBANON: CHAKRA 51 lEBANON STATS 37 CIVIL STRIFE INTRO |EDITORIAL ASSEM SALAM: THE CUSTODIAN OF VALUES The heart aches proudly when you see them, our knights when the demonstrators denounced the Syrian enemy: of the 1920s and 30s, refusing to dismount as if they “Calls for Lebanon’s independence from the Syrian were on a quest or a journey. -

Système National D'intégrité

Parlement Exécutif Justice Les piliersduSystèmenationald’intégrité Administration Institutions chargées d’assurer le respect de la loi Système national d’intégrité Étude surle Commissions de contrôle des élections Médiateur Les juridictions financières Autorités de lutte contre la corruption Partis politiques Médias Maroc 2014 Maroc Société civile Entreprises ÉTUDE SUR LE SYSTÈME NATIONAL D’INTÉGRITÉ MAROC 2014 Transparency International est la principale organisation de la société civile qui se consacre à la lutte contre la corruption au niveau mondial. Grâce à plus de 90 chapitres à travers le monde et un secrétariat international à Berlin, TI sensibilise l’opinion publique aux effets dévastateurs de la corruption et travaille de concert avec des partenaires au sein du gouvernement, des entreprises et de la société civile afin de développer et mettre en œuvre des mesures efficaces pour lutter contre ce phénomène. Cette publication a été réalisée avec l’aide de l’Union européenne. Le contenu de cette publication relève de la seule responsabilité de TI- Transparency Maroc et ne peut en aucun cas être considéré comme reflétant la position de l’Union européenne. www.transparencymaroc.ma ISBN: 978-9954-28-949-5 Dépôt légal : 2014 MO 3858 © Juillet 2014 Transparency Maroc. Tous droits réservés. Photo de couverture: Transparency Maroc Toute notre attention a été portée afin de vérifier l’exactitude des informations et hypothèses figurant dans ce -rap port. A notre connaissance, toutes ces informations étaient correctes en juillet 2014. Toutefois, Transparency Maroc ne peut garantir l’exactitude et le caractère exhaustif des informations figurantdans ce rapport. 4 REMERCIEMENTS L’Association Marocaine de Lutte contre la Corruption -Transparency Maroc- (TM) remercie tout ministère, institution, parti, syndicat, ONG et toutes les personnes, en particulier les membres de la commission consultative, le comité de pilotage et les réviseurs de TI pour les informations, avis et participations constructives qui ont permis de réaliser ce travail. -

2000 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor February 23, 2001

Morocco Page 1 of 41 Morocco Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2000 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor February 23, 2001 The Constitution provides for a monarchy with a Parliament and an independent judiciary; however, ultimate authority rests with the King, who presides over the Council of Ministers, appoints all members of the Government, and may, at his discretion, terminate the tenure of any minister, dissolve the Parliament, call for new elections, and rule by decree. The late King Hassan II, who ruled for 38 years, was succeeded by his son, King Mohammed VI, in July 1999. Since the constitutional reform of 1996, the bicameral legislature consists of a lower house, the Chamber of Representatives, which is elected through universal suffrage, and an upper house, the Chamber of Counselors, whose members are elected by various regional, local, and professional councils. The councils' members themselves are elected directly. The lower house of Parliament also may dissolve the Government through a vote of no confidence. In March 1998, King Hassan named a coalition government headed by opposition socialist leader Abderrahmane Youssoufi and composed largely of ministers drawn from opposition parties. Prime Minister Youssoufi's Government is the first government drawn primarily from opposition parties in decades, and also represents the first opportunity for a coalition of socialist, left-of-center, and nationalist parties to be included in the Government. The November 1997 parliamentary elections were held amid widespread, credible reports of vote buying by political parties and the Government, and excessive government interference. The fraud and government pressure tactics led most independent observers to conclude that the results of the election were heavily influenced, if not predetermined, by the Government. -

Enquête L'economiste-Sunergia La Moitié Du Gouvernement Peut S'en

2 EvènEmEnt Enquête L’Economiste-Sunergia La moitié du gouvernement peut s’en aller! • Pas une seule voix pour tout le équipe ne pèsent rien au regard du travail Les ministres qui réussissent secteur industriel et commercial que les citoyens attendent d’eux. Et pour faire bonne mesure, ne voilà-t-il El Houssaine Louardi 18% pas qu’un ministre politiquement impor- Aziz Rebbah 13% • Etrange phénomène avec tant, Mohand Laenser, se retrouve cité… Mustapha Ramid 11% avec l’opposition. Le gouvernement paye Aziz Akhannouch 9% Laenser! sans doute les rivalités puissantes qui op- Salaheddine Mezouar 6% posent le chef du Mouvement Populaire Mohamed Ouzzine 6% 5% avec le chef du PPS: pas un seul thème, Lahcen Daoudi • Le ministre de la Santé, El Mohamed Hassad 5% Cette année, nous n’avons pas mis pas un seul projet, sans qu’ils montrent Mohamed Boussaid 4% Benkirane dans la course avec ses Houssaine Louardi, reste le pré- publiquement leur désaccord, et sans que Mohamed Nabil Benabdellah 3% ministres, car les sondages précédents féré des Marocains le chef d’équipe n’entreprenne d’y mettre Mohamed El Ouafa 3% nous ont montré qu’il les écrase tant Mustapha El Khalfi 3% que leurs chiffres deviennent insigni- bon ordre. fiants. Apparemment, cela n’a pas Rachid Belmokhtar 2% Avec un étonnement navré, on notera suffi à les réhabiliter… C’EST clair, Benkirane peut virer Bassima Hakkaoui 2% la moitié de son gouvernement, personne que personne parmi les ministres et mi- Lahcen Haddad 1% ne s’en apercevra. Et parmi ceux qui res- nistres délégués chargés de la marche des Abdelkader Amara 1% tent, il n’y en a que quatre qui trouvent affaires et des entreprises n’est cité comme Mbarka Bouaïda 1% grâce, bien modestement. -

How Lebanese Elites Coopt Protest Discourse: a Social Media Analysis

How Lebanese Elites Coopt Protest Discourse: A Social Media Analysis ."3 Report Policy Alexandra Siegel Founded in 1989, the Lebanese Center for Policy Studies is a Beirut-based independent, non-partisan think tank whose mission is to produce and advocate policies that improve good governance in fields such as oil and gas, economic development, public finance, and decentralization. This report is published in partnership with HIVOS through the Women Empowered for Leadership (WE4L) programme, funded by the Netherlands Foreign Ministry FLOW fund. Copyright© 2021 The Lebanese Center for Policy Studies Designed by Polypod Executed by Dolly Harouny Sadat Tower, Tenth Floor P.O.B 55-215, Leon Street, Ras Beirut, Lebanon T: + 961 1 79 93 01 F: + 961 1 79 93 02 [email protected] www.lcps-lebanon.org How Lebanese Elites Coopt Protest Discourse: A Social Media Analysis Alexandra Siegel Alexandra Siegel is an Assistant Professor at the University of Colorado Boulder, a faculty affiliate of NYU’s Center for Social Media and Politics and Stanford's Immigration Policy Lab, and a nonresident fellow at the Brookings Institution. She received her PhD in Political Science from NYU in 2018. Her research uses social media data, network analysis, and experiments—in addition to more traditional data sources—to study mass and elite political behavior in the Arab World and other comparative contexts. She is a former Junior Fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and a former CASA Fellow at the American University in Cairo. She holds a Bachelors in International Relations and Arabic from Tufts University. -

Beirut 1 Electoral District

The 2018 Lebanese Parliamentary Elections: What Do the Numbers Say? Beirut 1 Electoral Report District Georgia Dagher +"/ Beirut 1 Founded in 1989, the Lebanese Center for Policy Studies is a Beirut-based independent, non-partisan think tank whose mission is to produce and advocate policies that improve good governance in fields such as oil and gas, economic development, public finance, and decentralization. This report is published in partnership with HIVOS through the Women Empowered for Leadership (WE4L) programme, funded by the Netherlands Foreign Ministry FLOW fund. Copyright© 2021 The Lebanese Center for Policy Studies Designed by Polypod Executed by Dolly Harouny Sadat Tower, Tenth Floor P.O.B 55-215, Leon Street, Ras Beirut, Lebanon T: + 961 1 79 93 01 F: + 961 1 79 93 02 [email protected] www.lcps-lebanon.org The 2018 Lebanese Parliamentary Elections: What Do the Numbers Say? Beirut 1 Electoral District Georgia Dagher Georgia Dagher is a researcher at the Lebanese Center for Policy Studies. Her research focuses on parliamentary representation, namely electoral behavior and electoral reform. She has also previously contributed to LCPS’s work on international donors conferences and reform programs. She holds a degree in Politics and Quantitative Methods from the University of Edinburgh. The author would like to thank Sami Atallah, Daniel Garrote Sanchez, Ayman Makarem, and Micheline Tobia for their contribution to this report. 2 LCPS Report Executive Summary Lebanese citizens were finally given the opportunity to renew their political representation in 2018—nine years after the previous parliamentary elections. Despite this, voters in Beirut 1 were weakly mobilized, and the district had the lowest turnout rate across the country. -

Political Party Mapping in Lebanon Ahead of the 2018 Elections

Political Party Mapping in Lebanon Ahead of the 2018 Elections Foreword This study on the political party mapping in Lebanon ahead of the 2018 elections includes a survey of most Lebanese political parties; especially those that currently have or previously had parliamentary or government representation, with the exception of Lebanese Communist Party, Islamic Unification Movement, Union of Working People’s Forces, since they either have candidates for elections or had previously had candidates for elections before the final list was out from the Ministry of Interior and Municipalities. The first part includes a systematic presentation of 27 political parties, organizations or movements, showing their official name, logo, establishment, leader, leading committee, regional and local alliances and relations, their stance on the electoral law and their most prominent candidates for the upcoming parliamentary elections. The second part provides the distribution of partisan and political powers over the 15 electoral districts set in the law governing the elections of May 6, 2018. It also offers basic information related to each district: the number of voters, the expected participation rate, the electoral quotient, the candidate’s ceiling on election expenditure, in addition to an analytical overview of the 2005 and 2009 elections, their results and alliances. The distribution of parties for 2018 is based on the research team’s analysis and estimates from different sources. 2 Table of Contents Page Introduction .......................................................................................................