Beirut 1 Electoral District

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

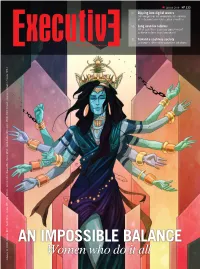

An Impossible Balance

March 2019 No 233 12 | Dipping into digital waters Convergences of awareness on several of Lebanon’s overdue cyber priorities 16 | Long overdue reforms What can the Lebanese government achieve in less than two years? 42 | Toward a cashless society Lebanon’s alternative payment solutions www.executive-magazine.com AN IMPOSSIBLE BALANCE Women who do it all Lebanon: LL 10,000 - Bahrain: BD2 - Egypt: EP20 - Jordan: JD5 - Iraq: ID6000 - Kuwait: KD2 - Oman: OR2 - Qatar: QR20 - Saudi Arabia: SR20 - Syria: SP200 - UAE: Drhm20 - Morocco: Drhm30 - Tunisia: TD5.5 - Tunisia: Drhm30 - Morocco: Drhm20 - UAE: SP200 - Syria: SR20 Arabia: - Qatar: - Saudi OR2 QR20 KD2 - Oman: ID6000 - Kuwait: JD5 - Iraq: LL 10,000 - Bahrain: - Egypt: BD2 EP20 - Jordan: Lebanon: 12 executive-magazine.com March 2019 EDITORIAL #233 Dismantling privilege A friend of mine, an ex-minister, once told me, “The Lebanese system works perfectly, like clockwork—but in all the wrong ways.” The money pledged by the international community at CEDRE requires long overdue structural reforms on our part. Take the deficit caused through subsidizing the failing public utility Electricité du Liban (EDL). To actually fix EDL would require our politicians to dismantle a parallel industry of which they are the benefactors. The corruption that keeps sectors like telecommunications and electricity profitable for our elite is entirely of their own making; and only through self-inflicted wounds would they be able to reform these sectors for the benefit of all Lebanese. The frequent foreign delegations who come to Lebanon surely laugh as they come out of another pointless high-level meeting, knowing that the problems they have raised were caused by these politicians, and the reforms that are so desperately needed have been blocked by these same men—and it has been men—for decades. -

Lebanon: Background and US Policy

Lebanon: Background and U.S. Policy name redacted Specialist in Middle Eastern Affairs April 4, 2014 Congressional Research Service 7-.... www.crs.gov R42816 Lebanon: Background and U.S. Policy Summary Lebanon’s small geographic size and population belie the important role it has long played in the security, stability, and economy of the Levant and the broader Middle East. Congress and the executive branch have recognized Lebanon’s status as a venue for regional strategic competition and have engaged diplomatically, financially, and at times, militarily to influence events there. For most of its independent existence, Lebanon has been torn by periodic civil conflict and political battles between rival religious sects and ideological groups. External military intervention, occupation, and interference have exacerbated Lebanon’s political struggles in recent decades. Lebanon is an important factor in U.S. calculations regarding regional security, particularly regarding Israel and Iran. Congressional concerns have focused on the prominent role that Hezbollah, an Iran-backed Shia Muslim militia, political party, and U.S.-designated terrorist organization, continues to play in Lebanon and beyond, including its recent armed intervention in Syria. Congress has appropriated more than $1 billion since the end of the brief Israel-Hezbollah war of 2006 to support U.S. policies designed to extend Lebanese security forces’ control over the country and promote economic growth. The civil war in neighboring Syria is progressively destabilizing Lebanon. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, more than 1 million predominantly Sunni Syrian refugees have fled to Lebanon, equivalent to close to one-quarter of Lebanon’s population. -

Project of Statistical Data Collection on Film and Audiovisual Markets in 9 Mediterranean Countries

Film and audiovisual data collection project EU funded Programme FILM AND AUDIOVISUAL DATA COLLECTION PROJECT PROJECT TO COLLECT DATA ON FILM AND AUDIOVISUAL PROJECT OF STATISTICAL DATA COLLECTION ON FILM AND AUDIOVISUAL MARKETS IN 9 MEDITERRANEAN COUNTRIES Country profile: 3. LEBANON EUROMED AUDIOVISUAL III / CDSU in collaboration with the EUROPEAN AUDIOVISUAL OBSERVATORY Dr. Sahar Ali, Media Expert, CDSU Euromed Audiovisual III Under the supervision of Dr. André Lange, Head of the Department for Information on Markets and Financing, European Audiovisual Observatory (Council of Europe) Tunis, 27th February 2013 Film and audiovisual data collection project Disclaimer “The present publication was produced with the assistance of the European Union. The capacity development support unit of Euromed Audiovisual III programme is alone responsible for the content of this publication which can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union, or of the European Audiovisual Observatory or of the Council of Europe of which it is part.” The report is available on the website of the programme: www.euromedaudiovisual.net Film and audiovisual data collection project NATIONAL AUDIOVISUAL LANDSCAPE IN NINE PARTNER COUNTRIES LEBANON 1. BASIC DATA ............................................................................................................................. 5 1.1 Institutions................................................................................................................................. 5 1.2 Landmarks ............................................................................................................................... -

The Monthly-March 2012 English

issue number 116 |March 2012 WAGE HIKE LEBANON AIRPORTS “the monthLy” interviews: RITA MAALOUF www.iimonthly.com • Published by Information International sal RENT ACT TWELVE EXTENSIONS AND A NEW LAW IS YET TO MATERIALIZE Lebanon 5,000LL | Saudi Arabia 15SR | UAE 15DHR | Jordan 2JD| Syria 75SYP | Iraq 3,500IQD | Kuwait 1.5KD | Qatar 15QR | Bahrain 2BD | Oman 2OR | Yemen 15YRI | Egypt 10EP | Europe 5Euros March INDEX 2012 4 RENT ACT 7 GLC AND BUSINESS OWNERS LOCK HORNS WITH NAHAS OVER WAGE HIKE 10 ElECTIONS 2013 (2) 12 WILL LEBANON OPERATE FOUR AIRPORTS OR ONLY ONE? 14 IDAL 16 THOUSANDS OF MOBILE PHONE LINES AT THE DISPOSAL OF SECURITY FORCES P: 21 P: 4 17 REOPENING OF BEIRUT Pine’s FOREST 18 VITAMINS & SUPPLEMENTS: DR. HANNA SAADAH 19 PSYCHOLOGICAL EFFECTS OF IMPOTENCE ON MEN IN THE MIDDLE EAST: MICHEL NAWFAL 20 ALF, BA, TA...: DR. SAMAR ZEBIAN 21 INTERVIEW: RITA MAALOUF P: 12 23 TORTURE - IRIDESCENCE 24 NOBEL PRIZES IN PHYSICS (2) 39 Mansourieh’s HIGH-VOLTAGE POWER 28 THE SOCIAL AND CULTURAL DEVELOPMENT LINES ASSOCIATION (INMA) 40 JANUARY 2012 TIMELINE 30 HOW TO BECOME A CLERGYMAN IN YOUR RELIGION? 43 EgYPTIAN ELECTIONS 31 POPULAR CULTURE 47 REAL ESTATE PRICES IN LEBANON - 32 DEBUNKING MYTH #55: DREAMS JANUARY 2012 33 MUST-READ BOOKS: CORRUPTION 48 FOOD PRICES - JANUARY 2012 34 MUST-READ CHILdren’s bOOK: CAMELLIA 50 VENOMOUS SNAKEBITES 35 LEBANON FAMILIES: HAWI FAMILIES 50 BEIRUT RAFIC HARIRI INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT - JANUARY 2012 36 DISCOVER LEBANON: CHAKRA 51 lEBANON STATS 37 CIVIL STRIFE INTRO |EDITORIAL ASSEM SALAM: THE CUSTODIAN OF VALUES The heart aches proudly when you see them, our knights when the demonstrators denounced the Syrian enemy: of the 1920s and 30s, refusing to dismount as if they “Calls for Lebanon’s independence from the Syrian were on a quest or a journey. -

CITY in SCENES Beirut City Center S C C S O L M E I P D O I E E B M I O R E I E E R P U N

r e t 2011 n e C y t i C t u r i e B MOMENTUM OF PLACE, PEOPLE IN MOTION: S E N CITY E C S N I IN Y T I C SCEN ES Beirut City Center T R O P E R L A U N N A E R E D I L O S 1 1 0 2 SOLIDERE ANNUAL REPORT Cities are made of scenes. Scenes that reflect how people move, congregate, pause, and adopt behaviors in the urban environment. These are the patterns that inspire our cityscapes. *** MOMENTUM OF PLACE, PEOPLE IN MOTION: CITY IN SCENES * SOLIDERE ANNUAL REPORT 2 0 1 1 * Foreword Characters make entrances and exits from the stage of reality just as cities trace the contours of civilizations through time. The currents of trade, conquest, and knowledge have, for millennia, propelled the history of the Mediterranean Basin. The people, architecture, and urban landscapes of its eastern port Beirut refract, like a prism, the stories that have accrued on this land throughout the centuries. Meditative and introspective, the Solidere Annual Report 2011 observes how people inhabit the spaces of Beirut city center. Just as the photography and text shed light on the trajectory of the built environment – its recon- struction, development, and future, so too does the Annual Report contemplate character and how individuals con- stitute architecture and place. Seasoned photojournalist Ziyah Gafic captures the latent dialogue between people and architecture. His camera turns quietly around the corner to eavesdrop on soft chatter in a garden. He peers up an outdoor staircase to follow the clacking of heels. -

An-Nahar, One of Lebanon's Most Influential Daily Newspapers

Four Generations of Tuenis at the Helm • Gebran Tueni founded An-Nahar in 1933. An-Nahar • Ghassan Tueni took over in 1947, when his father died. An-Nahar became the most authoritative and credible paper in the Arab region. Where History Lives • Gebran Tueni served as editor-in-chief from 2003 to 2005, when his life was cut short. His father Ghassan took over again until his death in 2012. n-Nahar, one of Lebanon’s most influential daily newspapers, • Nayla Tueni is the current deputy general manager of An-Nahar. Nayla A is 85 years old. It is considered Lebanon’s “paper of record.” American- is a journalist and a member of the Lebanese Parliament, like her late British author and journalist Charles Glass, who specializes in the Middle father Gebran had been. East, called An-Nahar “Lebanon’s New York Times.” Its archives’ tagline is: “The memory of Lebanon and the Arab world since 1933. What many don’t know is that the newspaper's offices themselves are a living memorial to its martyrs and a museum of its history. At the same time, it is still an active newsroom, where journalists report both for the paper and for annahar.com, the online version launched in 2012. Inside the tall glass tower at the northwest corner of Beirut’s Downtown, known as the An-Nahar building, Gebran Tueni’s On the desk is frozen morning in time. A slip of Dec. 12, of paper with Ghassan Tueni handwritten received the notes, a news that his business card only surviving and a small son was stack of books murdered. -

How Lebanese Elites Coopt Protest Discourse: a Social Media Analysis

How Lebanese Elites Coopt Protest Discourse: A Social Media Analysis ."3 Report Policy Alexandra Siegel Founded in 1989, the Lebanese Center for Policy Studies is a Beirut-based independent, non-partisan think tank whose mission is to produce and advocate policies that improve good governance in fields such as oil and gas, economic development, public finance, and decentralization. This report is published in partnership with HIVOS through the Women Empowered for Leadership (WE4L) programme, funded by the Netherlands Foreign Ministry FLOW fund. Copyright© 2021 The Lebanese Center for Policy Studies Designed by Polypod Executed by Dolly Harouny Sadat Tower, Tenth Floor P.O.B 55-215, Leon Street, Ras Beirut, Lebanon T: + 961 1 79 93 01 F: + 961 1 79 93 02 [email protected] www.lcps-lebanon.org How Lebanese Elites Coopt Protest Discourse: A Social Media Analysis Alexandra Siegel Alexandra Siegel is an Assistant Professor at the University of Colorado Boulder, a faculty affiliate of NYU’s Center for Social Media and Politics and Stanford's Immigration Policy Lab, and a nonresident fellow at the Brookings Institution. She received her PhD in Political Science from NYU in 2018. Her research uses social media data, network analysis, and experiments—in addition to more traditional data sources—to study mass and elite political behavior in the Arab World and other comparative contexts. She is a former Junior Fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace and a former CASA Fellow at the American University in Cairo. She holds a Bachelors in International Relations and Arabic from Tufts University. -

Political Party Mapping in Lebanon Ahead of the 2018 Elections

Political Party Mapping in Lebanon Ahead of the 2018 Elections Foreword This study on the political party mapping in Lebanon ahead of the 2018 elections includes a survey of most Lebanese political parties; especially those that currently have or previously had parliamentary or government representation, with the exception of Lebanese Communist Party, Islamic Unification Movement, Union of Working People’s Forces, since they either have candidates for elections or had previously had candidates for elections before the final list was out from the Ministry of Interior and Municipalities. The first part includes a systematic presentation of 27 political parties, organizations or movements, showing their official name, logo, establishment, leader, leading committee, regional and local alliances and relations, their stance on the electoral law and their most prominent candidates for the upcoming parliamentary elections. The second part provides the distribution of partisan and political powers over the 15 electoral districts set in the law governing the elections of May 6, 2018. It also offers basic information related to each district: the number of voters, the expected participation rate, the electoral quotient, the candidate’s ceiling on election expenditure, in addition to an analytical overview of the 2005 and 2009 elections, their results and alliances. The distribution of parties for 2018 is based on the research team’s analysis and estimates from different sources. 2 Table of Contents Page Introduction ....................................................................................................... -

The Case of Hezbollah in Lebanon by Mohamad Ibrahim BA, Lebanese

Survival through restrained institutionalization: The case of Hezbollah in Lebanon by Mohamad Ibrahim B.A., Lebanese American University, 2017 A THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS Department of Security Studies College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2019 Approved by: Major Professor Dr. Carla Martinez-Machain Copyright © Mohamad Ibrahim 2019. Abstract This thesis is an in-depth exploration of the evolving nature of domestic strategies adopted by Lebanon’s Hezbollah since its foundation in 1985 until the contemporary time. Based on Joel Migdal’s contributions to the literature on state-society relations, and Samuel Huntington’s understanding of institutionalization, it seeks to highlight and explain important transformations in Hezbollah’s political program, its sustained acquisition of arms, its social mobilization strategy, and its sensitive relationship with a de jure sovereign yet de facto weak Lebanese consociational system. The study proposes an explanation that combines Hezbollah’s ability to take advantage of the segmental autonomy that characterizes the power-sharing arrangements governing the Lebanese political system, and the overall existing political opportunity structure. The core argument is that Hezbollah has been able to become a powerful non-state actor through a process of restrained institutionalization which takes into consideration the need to sustain popular support on one hand, and the sensitive intricacies of Lebanon’s consociational system on the other hand. In other words, Hezbollah has invested its capacities in a way that maximizes its power in the existing political system, while remaining institutionally autonomous to a relative extent from it, and therefore becoming able to pursue its independent interests. -

Remaking Beirut: Contesting Memory, Space, and the Urban Imaginary of Lebanese Youth

Remaking Beirut: Contesting Memory, Space, and the Urban Imaginary of Lebanese Youth Craig Larkin∗ University of Exeter Throughout the centuries Beirut has had an endless capacity for reinvention and transformation, a consequence of migration, conquest, trade, and internal conflict. The last three decades have witnessed the city center’s violent self-destruction, its commercial resurrection, and most recently its national contestation, as opposi- tional political forces have sought to mobilize mass demonstrations and occupy strategic space. While research has been directed to the transformative processes and the principal actors involved, little attention has been given to how the next generation of Lebanese are negotiating Beirut’s rehabilitation. This article seeks to address this lacuna, by exploring how postwar youth remember, imagine, and spatially encounter their city. How does Beirut’s rebuilt urban landscape, with its remnants of war, sites of displacement, and transformed environs, affect and in- form identity, social interaction, and perceptions of the past? Drawing on Henri Lefebvre’s analysis of the social construction of space (perceived, conceived, and lived) and probing the inherent tensions within postwar youths’ encounters with history, memory, and heritage, the article presents a dynamic and complex urban imaginary of Beirut. An examination of key urban sites (Solidere’s` Down Town) and significant temporal moments (Independence Intifada) reveals three recur- ring tensions evident in Lebanese youth’s engagement with their city: dislocation and liberation, spectacle and participant, pluralism and fracture. This article seeks to encourage wider discussion on the nature of postwar recovery and the construc- tion of rehabilitated public space, amidst the backdrop of global consumerism and heritage campaigns. -

The Hariri Assassination and the Making of a Usable Past for Lebanon

LOCKED IN TIME ?: THE HARIRI ASSASSINATION AND THE MAKING OF A USABLE PAST FOR LEBANON Jonathan Herny van Melle A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2009 Committee: Dr. Sridevi Menon, Advisor Dr. Neil A. Englehart ii ABSTRACT Dr. Sridevi Menon, Advisor Why is it that on one hand Lebanon is represented as the “Switzerland of the Middle East,” a progressive and prosperous country, and its capital Beirut as the “Paris of the Middle East,” while on the other hand, Lebanon and Beirut are represented as sites of violence, danger, and state failure? Furthermore, why is it that the latter representation is currently the pervasive image of Lebanon? This thesis examines these competing images of Lebanon by focusing on Lebanon’s past and the ways in which various “pasts” have been used to explain the realities confronting Lebanon. To understand the contexts that frame the two different representations of Lebanon I analyze several key periods and events in Lebanon’s history that have contributed to these representations. I examine the ways in which the representation of Lebanon and Beirut as sites of violence have been shaped by the long period of civil war (1975-1990) whereas an alternate image of a cosmopolitan Lebanon emerges during the period of reconstruction and economic revival as well as relative peace between 1990 and 2005. In juxtaposing the civil war and the assassination of former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafic Hariri in Beirut on February 14, 2005, I point to the resilience of Lebanon’s civil war past in shaping both Lebanese and Western memories and understandings of the Lebanese state. -

Tueni, Kassir, and Chidiac… Ten Years Passed with No Progress in Investigations

Maharat Foundation rd Beirut on November 3P ,P 2015 Communiqué on the occasion of Impunity day: Tueni, Kassir, and Chidiac… Ten years passed with no progress in investigations The International Day to End Impunity for Crimes against Journalists comes ten years after the assassination of the two journalists Gebran Tueni and Samir Kassir and the attempt of assassination of the journalist May Chidiac in 2005, without bringing to justice or revealing the perpetrators, and until now no official progress in investigation has been made in their cases. Chidiac In the case of attempt of assassination of the journalist May Chidiac, she said during an interview with Maharat Foundation that she is waiting the Special Tribunal for Lebanon to find a link between her case and that of the assassination of the former prime minister Rafic Hariri so the tribunal can take over the case. Chidiac also considered that the “Lebanese authorities promote impunity through keeping the anonymity of the perpetrators despite the fact that those responsible for the 2005 assassinations are well known”. Tueni The same thing applies to the case of the journalist Gebran Tueni as emphasized by his daughter Michele Tueni to Maharat Foundation, who ensured that impunity contributed in the assassination of the victims where the perpetrators know that they will go unpunished. Tueni considered the consequences of impunity are dangerous especially that it urges journalists to put limits for their writings and to practice self censorship to protect their lives. Kassir The executive director of Samir Kassir Foundation Ayman Mhanna pointed that the case of Samir Kassir was transferred from the Lebanese and French judiciary to the Special Tribunal for Lebanon, and they are now waiting to link it to the case of assassination of Rafic Hariri.