Privatizing the Commons: Protest and the Moral Economy of National Resources in Jordan∗

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2013 Annual Report VISION CCESS Strives to Enable and Empower Individuals, Families and a Communities to Lead Informed, Productive and Culturally Sensitive Lives

2013 Annual Report VISION CCESS strives to enable and empower individuals, families and A communities to lead informed, productive and culturally sensitive lives. As a nonprofit model of excellence, we honor our Arab American heritage through community-building and service to all those in need, of every heritage. ACCESS is a strong advocate for cultural and social entrepreneurship imbued with the values of community service, healthy lifestyles, education and philanthropy. 2 / 2013 Annual Report Contents 2 4 OVERVIEW BOARD 6 38 DEPARTMENTS STATISTICAL REPORT 40 42 TREASURER’S REPORT DONORS / 2013 Annual Report 1 A MESSAGE FROM OUR LEADERS Hassan Jaber Wadad Abed Executive Director President PASSION TO SERVE. PASSION TO SUCCEED. PASSION FOR FAIRNESS AND JUSTICE. PASSION TO IMPROVE THE LIVES OF OTHERS. assion” describes the daily work by ACCESS staff members who ACCESS greatly improved in the areas of technology, human “P are determined to stand and work as a team in their efforts to create resources, and development. successful, happy and productive communities. In addition to our nearly 100 traditional programs that cover the It is that ferocity and passion that has given us great achievements this whole gamut of social, economic, health and educational programs, year. With ACCESS as a stronger institution, we can do more to assist, we also launched new innovative initiatives including ACCESS Growth improve and empower others; and work stronger as advocates on the local Center and Welcome Mat Detroit. and national levels for Arab American communities and all whom we serve. Welcome Mat Detroit, in partnership with Global Detroit, is a We made significant improvements in building our capacity to major initiative led by ACCESS and funded through the W.K. -

Years of Service

45 YEARS OF SERVICE ANNUAL REPORT 2016 ACCESS Strategic Priorities 2015-2020 A just and equitable society with the full participation of Build the leadership of young Arab Americans Vision Arab Americans Expand our leadership in the revitalization of Southeast Michigan, with a special focus on Detroit To empower communities to Improve the standing of Arab Americans in improve their economic, social American society Mission and cultural well-being Increase the capacity of ACCESS to deliver on our Mission and Vision Treasurer’s Highlights Table of 06 25 Report Areas of Donors Contents 08 Impact 26 Community Program Message From Board and 20 Partners 33 Locations 04 Our Leaders 05 Executive Staff Statistical 22 Report 2 ACCESS ANNUAL REPORT | 2016 3 Executive Board Executive Staff Rasha Demashkieh, President Hassan Jaber Message From Our Executive Director and Chief Executive Officer Jeff Antaya, Vice President Mary Jordan Abouljoud, Treasurer Maha Freij Deputy Executive Director and Chief Financial Officer Hussien Shousher, Secretary Hon. David Allen, At-Large Lina Hourani-Harajli Chief Operating Officer Leaders Basim Dubaybo, M.D., At-Large Devon Akmon Aoun Jaber, At-Large Director, Arab American National Museum (AANM) Since our founding as a grassroots organization, ACCESS has championed Hassan Bazzi the ideals of economic, social, health and racial equity. We serve as a safety net Director, Regional Opportunities for hundreds of thousands of individuals, while continuing to elevate and unify Emeritus Board Ali Baleed Almaklani Amne Darwish-Talab the voices of marginalized communities across Southeast Michigan and the Director, Social Services (East Dearborn Office) Barbara Aswad, Ph.D. nation. -

Aanm by the Numbers

ABOUT AANM TAKREEM Since opening its doors in 2005, the Arab American National Museum 2017 (AANM) has remained the nation’s only cultural institution to document, preserve and present the history, culture and contributions of Arab CULTURAL Americans. Located in Dearborn, Michigan, amid one of the largest concentrations of Arab Americans in the United States, AANM presents EXCELLENCE exhibitions and a wide range of public programs in Michigan and in major cities across the United States. AWARD AANM is one of just four Michigan Affiliates of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. and is accredited by the American Alliance of Museums. At a gala ceremony in Amman, Jordan, on Nov. 25, 2017, AANM is a founding member of Detroit-area arts collective CultureSource the Arab American National Museum was named a TAKREEM as well as the Immigration and Civil Rights Network of the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience. Most recently, AANM was selected to join Laureate and honored with the prestigious initiative’s the National Performance Network. Cultural Excellence Award. Founded in 2009 by veteran AANM is an institution of ACCESS, the Dearborn, Michigan-based human Lebanese TV presenter and producer Ricardo Karam, service agency founded in 1971. TAKREEM celebrates the accomplishments of Arab men and women who are making history in their own way. TAKREEM provides an alternative image of Arabs in the fields of science, culture, environment, education, humanitarian aid and economy – one that speaks of hard work, productivity, creativity, success and excellence, and one that offers both pride and inspiration to future generations. (FRONT COVER) Epicenter X artist Nugamshi demonstrates “calligraffiti” at the exhibition opening, July 2017. -

DETROIT BUSINESS MAIN 03-26-07 a 9 CDB.Qxd

DETROIT BUSINESS MAIN 03-26-07 A 9 CDB 3/23/2007 11:53 AM Page 1 March 26, 2007 CRAIN’S DETROIT BUSINESS Page 9 MARY KRAMER: On political civility and public service When former President Gerald sides of the partisan There’s no doubt its scholars, who are selected on the knows what works and what does- Ford died in December, his passing aisle. Former Gov. which side of the fence basis of financial need, not neces- n’t when it comes to education. prompted some soul-searching William Milliken cele- Carley is on. sarily the best high school grades. Carley will be part of the 25th about the hotly partisan state of our brates his 85th birthday “Name me one other Besides money to go to school, anniversary for that nonprofit this political and civic life these days. today. Happy birthday person who left their the scholars are contacted at least year. The foundation hopes to The lack of leadership and the to a Michigan treasure. entire estate, all their twice a week by foundation staff, draw more than 500 people to a big unwillingness to compromise wealth, to the future of by phone or e-mail. They attend fundraising dinner in May. among leaders in both political Loving a city, the city,” he says, refer- regular dinner meetings on their If you’re interested in making a parties in Michigan’s budget crisis ring to the Coleman A. campuses with staffers or volun- contribution to a scholarship pro- called to mind Ford’s remark on and its students Young Foundation, teers. -

A Case Study for the Detroit Institute of Arts and Its Relationship to the Detroit Arab Community 2001-2010

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Dissertations and Theses City College of New York 2012 Strategies for Engagement; A Case Study for the Detroit Institute of Arts and its Relationship to the Detroit Arab Community 2001-2010 Sarah Katherine Jorgensen CUNY City College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cc_etds_theses/145 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] !"#$"%&'%()*+#),-&$&%.%-") /)0$(%)("123)+*)"4%)5%"#+'")6-("'"1"%)+*)"4%)/#"()$-2)'"() #%7$"'+-(4'8)"+)"4%)5%"#+'")/#$9:/.%#'0$-)0+..1-'"3);<<=: ;<=<) !$#$4)>$"4%#'-%)?+#&%-(%-) FOR MY FATHER, JOSEPH GILBERT JORGENSEN (1934-2008), WHO INSPIRED ME TO FORMULATE QUESTIONS, TO LEAD AN ANALYTICAL LIFE AND TO ENGAGE IN COMMUNITY ISSUES. Table of Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS INTRODUCTION 1. THE DETROIT INSTITUTE OF ART 2. RENOVATION 3. MUSEUM EDUCATION AND OUTREACH SINCE REINSTALLATION 4. DETROIT AND ARAB AMERICAN IMMIGRANTS 5. STRATEGIC THINKING AND PLANNING ABOUT OUTREACH 6. MUSEUMS AND ARAB AND ISLAMIC ATTITUDES TOWARDS ART 7. OPPORTUNITIES TO BRING ABOUT CHANGE CONCLUSION ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my thesis advisor, Harriet Senie of the City University of New York and my thesis reader Curtiss Rooks of Loyola Marymount University for their invaluable insight and editorial help. I would also like to thank Janice Freij at the Arab American National Museum for her review. I interviewed many museum professionals and some in the academy. Those individuals helped me to better understand the culture of museums and those institutions where they worked. -

2011 Annual Report

2011 ANNUAL REPORT VISION ACCESS STRIVes TO empower and enable individuals, families and communities to lead informed, productive, culturally sensitive and fulfilling lives. ACCESS honors its Arab American heritage while serving as a nonprofit model of excellence. We are dedicated to community-building and focused on service to all those in need. ACCESS is a strong advocate for cultural and social entrepreneurship as well as the values of community service, healthy lifestyles, education and philanthropy. CONTENTS Message From The Board President . 2 Message From The Executive Director . 3 Executive Board . 4 Arab Americans Of The Year . 5 Social Services . 6 Community Health & Research Center . 10 Employment & Training . 18 Youth & Education . 21 NNAAC . 25 Center For Arab American Philanthropy . 30 Arab American National Museum . 33 Statistical Report . 37 Treasurer’s Report . 38 2010 - 2011 Donors . 41 Committee Members & Partners . 45 ACCESS Locations . Inside Back Cover 2 A MESSAGE FROM THE PRESIDENT Wadad Abed, President t is both humbling and inspiring to then, because ACCESS is a wraparound of the whole, using their collective energy serve as ACCESS board president. service provider, we’re able to refer to create change. Over the past year, I’ve seen firsthand that person or family to other services That’s how ACCESS’ local programs I how the supporters of ACCESS – from that will help move them beyond the have blossomed into three national our volunteers to our employees to our immediate need and, hopefully, into full initiatives: the National Network for board members – work long and hard to civic participation. Arab American Communities (NNAAC), keep ACCESS strong as our struggling So, for the child struggling to keep up the Arab American National Museum economy continues to put pressure on in school we not only provide tutoring, (AANM) and the Center for Arab American those in our community who are most we also look at the family’s needs: Do Philanthropy (CAAP). -

Palestinian Music and Song

Palestinian Music and Song Public Cultures of the Middle East and North Africa Paul Silverstein, Susan Slyomovics, and Ted Swedenburg, editors Palestinian Music and Song Expression and Resistance since 1900 Edited by Moslih Kanaaneh, Stig- Magnus Thorsén, Heather Bursheh, and David A. McDonald Indiana University Press Bloomington and Indianapolis This book is a publication of Indiana University Press Office of Scholarly Publishing Herman B. Wells Library 350 1320 East 10th Street Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA www.iupress.indiana.edu Telephone orders 800- 842- 6796 Fax orders 812- 855- 7931 © 2013 by Indiana University Press All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, in clud ing photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of Ameri can University Presses’ Resolution on Permissions constitutes the only exception to this prohibition. > The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the Ameri can National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48–1992. Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Palestinian music and song : expression and resistance since 1900 / edited by Moslih Kanaaneh, Stig-Magnus Thorsén, Heather Bursheh, and David A. McDonald. pages cm — (Public cultures of the Middle East and North Africa) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-253-01098-8 (cloth : alkaline paper) — ISBN 978-0-253-01106-0 (paperback : alkaline paper) — ISBN 978-0-253-01113-8 (e-book) 1. -

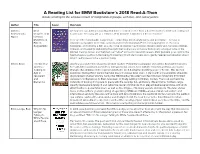

A Reading List for EMW Bookstore's 2018 Read-A-Thon

A Reading List for EMW Bookstore’s 2018 Read-A-Thon books relating to the empowerment of marginalized groups, self-love, and social justice Author Title Cover Overview Adichie, Dear A few years ago, Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie received a letter from a dear friend from childhood, asking her Chimamanda Ijeawele, or A how to raise her baby girl as a feminist. Dear Ijeawele is Adichie's letter of response. Ngozi Feminist Manifesto in Here are fifteen invaluable suggestions—compelling, direct, wryly funny, and perceptive—for how to Fifteen empower a daughter to become a strong, independent woman. From encouraging her to choose a Suggestions helicopter, and not only a doll, as a toy if she so desires; having open conversations with her about clothes, makeup, and sexuality; debunking the myth that women are somehow biologically arranged to be in the kitchen making dinner, and that men can "allow" women to have full careers, Dear Ijeawele goes right to the heart of sexual politics in the twenty-first century. It will start a new and urgently needed conversation about what it really means to be a woman today. Ameri, Anan The Scent of Journey to a world little known to western readers. Palestinian sociologist and activist Anan Ameri weaves Jasmine: her sometimes poignant, sometimes funny personal experiences with the historical, political, and social Coming of changes that dominated the region in which she lived during the first thirty years of her life. This memoir Age in comprises twenty-three stories that take place in various Arab cities. It starts with a few vignettes about the Jerusalem displacement of Anan’s family during the 1948 Nakba (“Disaster”) and her constant movement from West and Jerusalem, to Damascus, to East Jerusalem, to finally settling in Amman, Jordan. -

Annual Report2014

TEN YEARS OFBUILDING COMMUNITY THROUGHANNUAL THEREPORT 2014 ARTS-15 ABOUT AANM CELEBRATING its 10th Anniversary Year from May 15 2015 through May 2016, the Arab American National - Museum (AANM) documents, preserves and presents the history, culture and contributions of Arab Americans. Located in Dearborn, Michigan, amid one of the largest concentrations of Arab Americans in the country, AANM remains the only museum of its type in the United States. It presents exhibitions and public programs in southeast Michigan and in major cities across the nation. 2014 AANM is southeastern Michigan’s only Affiliate of the Smithsonian Institution. In 2008, the Museum was the recipient of a Coming Up Taller Award given by the President’s Committee on the Arts and the Humanities. AANM is a founding member of both the Immigration and Civil Rights Sites of Conscience Network and CultureSource. In 2013, AANM earned accreditation from the American Alliance of Museums, an industry PORT seal of approval achieved by just 7% of America’s 22,500 cultural institutions. AANM is a program of ACCESS, the Dearborn, Mich.- RE ANNUAL based human service agency founded in 1971. FROM THE AANM DIRECTOR Dear Friends and Supporters, It’s hard to believe a decade has passed since the opening of the Arab American National Museum in 2005. In a relatively short amount of time, we have managed to accomplish so much together. Your AANM has become southeast Michigan’s only Affiliate of the Smithsonian Institution. The Museum joined the ranks of just 7% of museums nationwide in achieving accreditation from the American Alliance of Museums. -

AANM-AR-2019-20-Web.Pdf

ABOUT AANM NATIONAL ADVISORY BOARD + STAFF OCT. 1, 2019 - SEPT. 30, 2020 National Advisory Board AANM Staff Honorary Members Diana Abouali, PhD | Director Her Majesty Queen Noor Al-Hussein of Jordan Jumana Salamey, AuD | Deputy Director Congresswoman Debbie Dingell Cushla J. (Hendry) Ahmad | Executive Assistant Yousif B. Ghafari Rasha Almulaiki | Educator Irene Hirano * Lejla Bajgoric | Community Events Organizer Secretary Ray LaHood Elizabeth Barrett-Sullivan | Curator of Exhibits Patricia Mooradian Amal Beydoun | Development Manager Kathy Najimy Brandon Coulter | Communications Specialist Congressman Nick Rahall Greta Anderson Finn | Grant Writer Betty Sams Aziza Ghanem | Administrative Assistant Tony Shalhoub Kathryn Grabowski | Curator of Public Programming George Takei Ahmed Jamalaldin | Maintenance Technician Elizabeth Karg | Librarian Executive Committee Ayah Krisht | Media Designer Fawwaz Ulaby, Chair Crystal McColl | Curatorial Specialist Ismael Ahmed Edwina Murphy | Archivist Raghad Farah Lujine Nasralla | Communications Specialist Edward M. Gabriel Iman Saleh | Administrative Support Sandra Gibson Dave Serio | Educator & Public Programming Specialist Leila Hilal Ruth Ann Skaff | Senior Outreach Advisor Sharif Hussein Matthew Jaber Stiffler, PhD | Research & Content Manager Manal Saab, Ex Officio Danya Zituni | Educator Aziz Shaibani Mouna Haddad Khoury, Chair, Friends of AANM General Membership Evelyn Alsultany Since opening its doors in 2005, the Arab American National Museum (AANM) remains the nation’s only cultural institution Anan Ameri that documents, preserves and presents the history, culture and contributions of Arab Americans. Located in Dearborn, Nazeeh Aranki Michigan, amid one of the largest concentrations of Arab Americans in the United States, AANM presents original Bassam Barazi exhibitions, cutting-edge art, film screenings and performances in Michigan and in major cities across the U.S., and Maya Berry continually documents the history and experiences of Arab Americans.