Artisan Clusters – Some Policy Suggestions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Bank Document

GLOBAL ENVIRONMENT 33977 FACILITY Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Quarterly Operational Report April 1995 Public Disclosure Authorized GEF Public Disclosure Authorized development,agencies, national institutions, (GEF) is a financial tions, bilateral T mechanismhe Global Environment that provides Facility grant and concessional funds non-governmental organizations (NGOs), private sector to developing countries for projects and activities that aim entities, and academic institutions. The GEF also comprises to protect the global environment. GEF resources are avail- a Small Grants Programme available for projects in the able for projects and other activities that address climate four focal areas that are put forward by grassroots groups change, loss of biological diversity, pollution of international and NGOs in developing countries. waters, and depletion of the ozone layer. Countries can The Quarterly Operational Report is designed to pro- obtain GEF funds if they are eligible to borrow from the vide a comprehensive review of, and a status report on, the World Bank (IBRD and/or IDA) or receive technical assis- GEE work program. A brief description of each of the GEE's tance grants from UNDP through a country program. projects organized alphabetically by region can be Responsibility for implementing GEF activities is found on pages 8-J8. Each description lists the name of the shared by the United Nations Development Programme UNDP, UNEP or World Bank Task Manager responsible for (UNDP), the United Nations Environment Programme the project. Inquiries about specific projects should be (UNEP) and the World Bank. UNDP is responsible for referred to the responsible Task Manager. Their telephone technical assistance activities, capacity building, and the and fax numbers can be found on pages 63 and 64. -

Profile of the Medicinal and Economic Plants of Laspur Valley Chitral, Pakistan

Arom & at al ic in P l ic a n d t e s M ISSN: 2167-0412 Medicinal & Aromatic Plants Research Article Profile of the Medicinal and Economic Plants of Laspur Valley Chitral, Pakistan Naheeda Bibi* Department of Botany, Shaheed BB University, Sub-Campus Chitral, Pakistan ABSTRACT The inhabitants of Laspur valley of Chitral have always been used plant resources for medicine, human and other animals food, vegetable, housing, timber, condiment, facial mask, fuel, ornamental and other multi purposes, from many year ago. A total of 212 species belonging to 55 families including 2 gymnosperms families (4 species), 5 monocots families (24 species) as well as 48 dicots families (184 species) have been recorded from the research area during 2013-2014. Family Asteraceae contributed the greatest number of species (30), after that Fabaceae (20 species), Poaceae (15 species), Brassicaceae (14 species), Rosaceae (12 species), Apiaceae (9 species), Solanaceae, Ranunculaceae and Salicaceae (each with 7 species), Lamiaceae (6 species), Polygonaceae (5 species), Amaranthaceae and Malvaceae (each with 4 species) and Cupressaceae, Boraginaceae, Caryophyllaceae, Chenopodiaceae, Cucarbitaceae, Grossulariaceae, Cyperaceae and Alliaceae (each with 3 species). All the other families are represented by less than 3 species. Ethnobotanically 155 plants were used as fodder including gymnosperms with one species and angiosperms with 154 species (135 dicots and 19 monocots), medicinal 100 species including 2 species of gymnosperms and 98 species of angiosperms (89 dicots and 9 monocots), fire wood 47 species including 4 gymnosperms and 43 angiosperms, vegetables 36 species of angiosperms, ornamental 31 species among which gymnosperms have one species and 30 species in an angiosperms (27 dicots and 3 monocots), timber 17 species including one species of gymnosperms and 16 species of angiosperms, fruit 10 species of angiosperms, facial mask/facial cream 10 species (9 angiosperms and 1 gymnosperm). -

Minutes of 17Th MDB Meeting.Pdf

Government of Pakistan Ministry of National Health Services, Regulation & Coordination Drug Regulatory Authority of Pakistan *********** MINUTES OF THE 17TH MEETING OF THE MEDICAL DEVICE BOARD (MDB) HELD ON 13-07-2020 17th meeting of the Medical Device Board (MDB) was held in the office of Drug Regulatory Authority of Pakistan, TF Complex, G-9/4, Islamabad on 13th July, 2020. The Secretary MDB referred to Sub-rule (9), Rule (59) of Medical Devices Rules, 2017 where in the absence of Chairman MDB, members may elect one of the member to preside over the meeting. The members unanimously elected Prof. Dr. Syed Mohsin Naveed Abbas, Consultant Nephrologist & Transplant Physician, Head of Department of Nephrology & Dialysis, Cantt General Hospital, Rawalpindi/ Federal Administrator, Human Organ Transplant Authority (HOTA) to preside over the meeting as Chairman. Subsequently meeting was chaired by Dr. Syed Mohsin Naveed Abbas, Consultant Nephrologist & Transplant Physician, Head of Department of Nephrology & Dialysis, Cantt General Hospital, Rawalpindi/ Federal Administrator, Human Organ Transplant Authority (HOTA) and was attended by the following:- S.No. Name and Designation / Department Position in the MDB 1. Prof. Dr. Syed Mohsin Naveed Abbas, Consultant Nephrologist Chairman & Transplant Physician, Head of Department of Nephrology & Dialysis, Cantt General Hospital, Rawalpindi/ Federal Administrator, Human Organ Transplant Authority (HOTA) 2. Mr. Imranullah, Chief Drug Inspector, Abbottabad, KPK, Member (Nominee of Director General Health, Khyber Pukhtunkhwa). 3. Professor Sami Saeed, Professor of Chemical Pathology, Member Foundation University Medical College, Islamabad. 4. Mrs. Tazeen S. Bukhari, Biomedical Equipment Planner, Member Saleem Memorial Trust Hospital, Lahore. 5. Dr. Prof. Saqib Shafi Sheikh, Executive Director, Punjab Member Institute of Cardiology, Lahore. -

Ethnobotanical Notes on Woody Plants of Rech Valley, Torkhow, District Chitral, Hindu-Kush Range, Pakistan

Scholarly Journal of Agricultural Science Vol. 3(11), pp. 468-472 November, 2013 Available online at http:// www.scholarly-journals.com/SJAS ISSN 2276-7118 © 2013 Scholarly-Journals Full Length Research Paper Ethnobotanical notes on woody plants of Rech Valley, Torkhow, District Chitral, Hindu-Kush range, Pakistan Fazal Hadi*, Abdul Razzaq, Aziz-ur-Rahman and Abdur Rashid Centre of Plant Biodiversity, University of Peshawar, Peshawar, Pakistan. Accepted 23 October, 2013 District Chitral is located on the extreme north of Pakistan, a hilly state of the Hindu-Kush range with unique phytogeographic position having both Sino-Japanese and Irano-Turanian floristic regions. The present study was aimed to look into the diversity of woody plant resources that are used by local people for curing various ailments of strategically important Rech valley of Torkhow sub-division, district Chitral. It was found that 29 medicinal plants belonging to 21 genera and 16 families were used locally for different ailments and other purposes. Rosaceae was a leading family having 8 medicinal plants, followed by Salicaceae with three species. Eleagnaceae, Fabaceae and Moraceae have two species each. The remaining families are represented by one species each. For documenting the ethno- medicinal and socio-economic profile of the study area, a simple questionnaire was developed and filled through interview from representative of various ethnic groups. The leaves and fruits were found to be used mostly for curing the various health problems. Key words: Ethnomedicinal, woody plants, Rech valley, Torkhow, district Chitral, Hindu-Kush range, Pakistan. INTRODUCTION The use of plants by man for different purposes is dated district of the Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province with 14850 back to the origin of human life on earth. -

Climate Change Profile of Pakistan

Climate Change Profi le of Pakistan Catastrophic fl oods, droughts, and cyclones have plagued Pakistan in recent years. The fl ood killed , people and caused around billion in damage. The Karachi heat wave led to the death of more than , people. Climate change-related natural hazards may increase in frequency and severity in the coming decades. Climatic changes are expected to have wide-ranging impacts on Pakistan, a ecting agricultural productivity, water availability, and increased frequency of extreme climatic events. Addressing these risks requires climate change to be mainstreamed into national strategy and policy. This publication provides a comprehensive overview of climate change science and policy in Pakistan. About the Asian Development Bank ADB’s vision is an Asia and Pacifi c region free of poverty. Its mission is to help its developing member countries reduce poverty and improve the quality of life of their people. Despite the region’s many successes, it remains home to a large share of the world’s poor. ADB is committed to reducing poverty through inclusive economic growth, environmentally sustainable growth, and regional integration. Based in Manila, ADB is owned by members, including from the region. Its main instruments for helping its developing member countries are policy dialogue, loans, equity investments, guarantees, grants, and technical assistance. CLIMATE CHANGE PROFILE OF PAKISTAN ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK www.adb.org Prepared by: Qamar Uz Zaman Chaudhry, International Climate Technology Expert ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) © 2017 Asian Development Bank 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City, 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines Tel +63 2 632 4444; Fax +63 2 636 2444 www.adb.org Some rights reserved. -

Crisis Response Bulletin

IDP IDP IDP CRISIS RESPONSE BULLETIN July 22, 2015 - Volume: 1, Issue: 27 IN THIS BULLETIN HIGHLIGHTS: English News 03-23 KP CM orders rapid relief work in Flood-Hit Chitral 03 Rains trigger Flash Floods in several parts of Pakistan 03 Significant flood forecast for river Indus at Kalabagh and Chashma 05 Natural Calamities Section 03-08 Senate committee to probe Karachi heat wave, loadshedding 05 Safety and Security Section 09-14 Country still vulnerable to floods 06 Army chief offers Eid prayers with soldiers in Waziristan 09 Public Services Section 15-23 Sindh govt extends Rangers tenure in Karachi for a year 10 Pakistan files complaint with UNMOGIP over 'Indian ceasefire 10 Maps 04,24-32 violations' Interior ministry starts registration of NGOs, madrassas, SC told 10 Apex committee decision: Sindh to mount crackdown on RAW affiliates13 Urdu News 46-33 China-funded LNG project to turn into Iran- Pakistan gas pipeline 15 Rs 248 billion being spent for different power projects 15 Natural Calamities Section 46-44 Gas defaulters punished with disconnections 17 Power, gas supply: Zero-rating facility withdrawal criteria laid down 18 Safety and Security section 43-42 Water and power secretary suspends PESCO officials over poor 20 Public Service Section 41-33 performance PAKISTAN WEATHER MAP MAXIMUM TEMPERATURE MAP OF PAKISTAN RELATIVE HUMIDITY MAP OF PAKISTAN WIND SPEED MAP OF PAKISTAN CHITRAL FLASH FLOOD DAMAGES - 2015 ACCUMULATED RAINFALL MAP - PAKISTAN MAPS PAKISTAN - RESERVOIRS & RIVERS FLOW MAP VEGETATION ANALYSIS MAP OF PAKISTAN CNG -

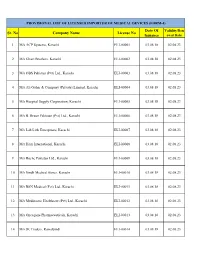

Provisional List of Licensed Importer of Medical Devices (Form-4)

PROVISIONAL LIST OF LICENSED IMPORTER OF MEDICAL DEVICES (FORM-4) Date Of Validity/Ren Sr. No Company Name License No Issuance ewal Date 1 M/s ACP Systems, Karachi ELI-00001 03.08.18 02.08.23 2 M/s Ghazi Brothers, Karachi ELI-00002 03.08.18 02.08.23 3 M/s OBS Pakistan (Pvt) Ltd., Karachi ELI-00003 03.08.18 02.08.23 4 M/s Ali Gohar & Company (Private) Limited, Karachi ELI-00004 03.08.18 02.08.23 5 M/s Hospital Supply Corporation, Karachi ELI-00005 03.08.18 02.08.23 6 M/s B. Braun Pakistan (Pvt) Ltd., Karachi ELI-00006 03.08.18 02.08.23 7 M/s Lab Link Enterprises, Karachi ELI-00007 03.08.18 02.08.23 8 M/s Ham International, Karachi ELI-00008 03.08.18 02.08.23 9 M/s Roche Pakistan Ltd., Karachi ELI-00009 03.08.18 02.08.23 10 M/s Sindh Medical Stores, Karachi ELI-00010 03.08.18 02.08.23 11 M/s BSN Medical (Pvt) Ltd., Karachi ELI-00011 03.08.18 02.08.23 12 M/s Medinostic Healthcare (Pvt) Ltd., Karachi ELI-00012 03.08.18 02.08.23 13 M/s Oncogene Pharmaceuticals, Karachi ELI-00013 03.08.18 02.08.23 14 M/s JK Traders, Rawalpindi ELI-00014 03.08.18 02.08.23 PROVISIONAL LIST OF LICENSED IMPORTER OF MEDICAL DEVICES (FORM-4) Date Of Validity/Ren Sr. No Company Name License No Issuance ewal Date 15 M/s Briogene Pvt Ltd, Karachi ELI-00015 03.08.18 02.08.23 16 M/s Bay-G Pharma, Rawalpindi ELI-00016 03.08.18 02.08.23 17 M/s Anwar & Sons, Rawalpindi ELI-00017 03.08.18 02.08.23 18 M/s Standard Supply Agencies, Peshawar ELI-00018 03.08.18 02.08.23 19 M/s Abbott Laboratories (Pakistan) Ltd., Karachi ELI-00019 03.08.18 02.08.23 20 M/s Sadqain Healthcare (Pvt) -

Indigenous Utilization of Weed Flora of District Charsadda, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa

Science Arena Publications Specialty Journal of Agricultural Sciences ISSN: 2412-737X Available online at www.sciarena.com 2018, Vol 4 (2): 9-20 Indigenous Utilization of Weed Flora of District Charsadda, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Muhammad Nauman Khan*, Abdul Razzaq, Fazal Hadi, Naushad Khan, Abdul Basit, Farmanullah Jan Department of Botany, University of Peshawar, Peshawar, Pakistan. *Corresponding Author Email: [email protected] Abstract: District Charsadda is a very important center of plant biodiversity in the central plain of Peshawar valley, Pakistan. The present study was carried out during 2015-2016 to investigate the ethno botanical profile of common weed flora present in district Charsadda, KP, Pakistan. The study revealed that there were 40 weed species belonging to 21 families. Among them, 25 weeds were annual herbs, 9 weeds were perennial herbs, three were annual grass, one was a climbing herb, one was a parasitic weed, and one was rhizomatic grass. The dominant families were Asteraceae, Fabaceae and Poaceae having 5 species (12.5 %) each followed by Ranunculaceae with 3 species (7.5 %). Plants were systematically arranged into botanical names, local names, families, habits, habitats, used parts, flowering periods, localities, and ethno botanical uses. The main aim of the study is the documentation and collection of ethno botanical information of the weed flora growing in the area. Keywords: Indigenous Uses, Weed Species, Local Uses, Annual, Perennial, District Charsadda, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa INTRODUCTION Charsadda derives its name from its headquarters’ town. At the time of Alexander's invasion, Charsadda was known as Pushkalavati (The Lotus city). Charsadda district lies in the central plain of Peshawar valley between 34-03' to 34-28' North Latitude and 71-28' to 71-33' East Longitudes with area of 996 square kilometres. -

DATABASE of NGO ACTIVITIES ( 7Th Edition )

ACBAR Agency Coordinating Body for Afghan Relief DATABASE OF NGO ACTIVITIES ( 7th Edition ) Volume Ill: Agency 2 Rehman Baba Road Univ. P.O. Box 1084 University Town Peshawar, N. W. F. P. Pakistan Tel : (0521) 44392, 40839, 45347 Fax : (0521) 840471 February. 1995 INTRODUCTION I am very pleased to make available the ACBAR Database for 1994.This is now theseventh edition of this publication, that ACBAR has compiled, since 1988. This year, in order to control the size and related costs for the future, we have decidedto publish the Database in two separate parts: Part A: Closed and Discontinued Projects, as at end 1994: - presented in four separate volumes: Volume I Location - Province/District Volume II Sector Volume IIIAgency Volume IVRefugees in Pakistan. - this will NOT be reprinted. Part B: Ongoing Projects; and Proposed and Surveyed activities: Volume V Ongoing Projects - by Location; Sector, Agency; Refugees; and Proposed & Surveyed Activities. - this will be updated during 1995. The five volumes of the Database, which total some 1400 pages, have taken considerable time and effort to prepare. They provide a compilation of the activities as reported by 272 Non -Government Organisations (NGOs) working for Afghanistan. Whilst most agencies are Peshawar based, activities are also reported for agencies located in Islamabad, Quetta and inside Afghanistan. Whilst ACBAR has not had the ability to confirm the information provided, I am confident that this publication provides as accurate a picture as possible of NGO activities related to Afghanistan and refugees over the period to 1994. I would like to express my gratitude to agencies for providing the data. -

Child Protection Sub Cluster Bulletin#9

Child Protection Sub Cluster Monthly Bulletin ISSUE 09 / Jun 2012 Child in a Community based Protective Space established in a return area in district Badin, UC Badin II ©UNICEF/PAK2011/Atteeq Bashir Highlights In this issue Highlights P.1 The number of IDPS families from Khyber Agency is 68,426 fami- KP/FATA IDP influx P.2 Early Recovery Sindh P.3 lies (315,696 Individuals), where 12,080 families living in Jalozai Useful Resources P.4 Camp and 56,346 families opted to reside in host areas. UNICEF has provided services to 3,255 children and 1,115 women through 21 PLaCES. The Child Protection Monthly Bulletin Sindh Early Recovery Response for Flood 2011 emergency is reach shares the overall needs, progress 93% by attaining the figure of 280 protective spaces in reference and gaps of the child protection sec- tor in response to the 2011 floods in of set targets of 300 protective spaces. The protective spaces had Sindh and Balochistan and the ongo- serves a total of 29,884 children including 13,780 girls. 11,031 ing emergency/displacement in FATA women also benefited from these protective spaces, including and KP. 9,215 in last month. The Child Protection Sub Cluster has SC has celebrated the event of “Day Against Child Labour” in dis- more than 100 member organisations throughout Pakistan and is led by trict Mirpurkhas, Sindh, on 12 June 2012. UNICEF. Page 1 of 4 FATA / Khyber Pakhtunkhwa UNICEF is also running 15 PLaCES in New Durrani IDP Response 2012 Camp of Kurram Agency, benefiting 2,512 children Currently there are 68,426 families (315,696 individu- and 703 women. -

Download the Full Paper

Int. J. Biosci. 2019 International Journal of Biosciences | IJB | ISSN: 2220-6655 (Print), 2222-5234 (Online) http://www.innspub.net Vol. 14, No. 5, p. 413-424, 2019 RESEARCH PAPER OPEN ACCESS Ethnomedicinal exploration of plant resources of Terich Valley, Hindukush Range Chitral, Pakistan Akhtar Zaman*, Lal Badshah Department of Botany, University of Peshawar, Pakistan Key words: Ethnobotanical, FIV, RFC, Traditional treatments, Terich Valley, Chitral, Pakistan. http://dx.doi.org/10.12692/ijb/14.5.413-424 Article published on May 26, 2019 Abstract A detailed study was carried out during 2017-2019 to record information on traditional knowledge of ethno medicinalplants used by the local community for treatment of various human disorders of Terich Valley Hindukush Range, District Chitral. Data about medicinal plants were collected from local community through open ended questionnaires, corner meetings, interviews and group discussion. A total of 64 ethnomedicinal plant species belonging to 56 genera and 31 families was documented, in which the herb species (39) dominated the list followed by trees (14) and shrubs (11). Family importance value (FIV) indicated that Asteraceae (8 species, 12.5%) was the leading family that contributed the largest number of species, followed by Apiaceae (7 species, 10.93), Rosaceae (6 species, 9.37%) and Lamiaceae (4 species, 6.25%) respectively.From the result it was recorded that leaves and fruits are the frequently used plant parts in the preparation of medicinal plantrecipes. It was concluded that over-harvesting, excessive use, habitat loss, degradation, deforestation, agriculture expansion, overpopulation, invasion of invasive alien species andover grazing are the prominentstresses to the medicinal plant biodiversity of the valley. -

Curriculam Vitae

1 CURRICULAM VITAE A NAME: DR. GHULAM DASTAGIR FATHER NAME: ABDUL JALIL DESIGNATION: PROFESSOR INSTITUTION: DEPARTMENT OF BOTANY, UNIVERSITY OF PESHAWAR, PESHAWAR, PAKISTAN TEACHING AND RESEARCH EXPERIENCE Date of appointment on adhoc 4-4-1997 Date of regular appointment as Lecturer 3-9-2001 Date of appointment as Assistant Professor 15-7-2010 Date of appointment as Associate Professor 17-6-2014 Date of appointment as Professor 30-10-2015 Length of service (18 years and 8 months) B NUMBER OF PUBLICATIONS 35+7=42 (Publication list attached) C. SUBJECTS TAUGHT AT MASTER LEVEL SINCE 1997 1. Medicinal plants and Economic Botany. 2. Environmental Biology 3. Plant Nutrition and Soil Fertility 4. Advances in medicinal plants D. (a) SUBJECTS TAUGHT to M. PHIL LEVEL SINCE 1997 1. Plant biodiversity and conservation 2. Pharmacognosy 3. Environmental Health and problems D (b) SUBJECTS TAUGHT to PhD LEVEL SINCE 2013 1. Plant biodiversity and conservation 2. Environmental Health and problems 2 D (c) SUBJECTS TAUGHT to BS-SEMESTER LEVEL SINCE 2016 1. Plant and Society 2. Aromatic and high valued medicinal plants 3. Plant biodiversity and conservation 4. Environmental Sciences SUPERVISION OF THESES (SUPERVISED 8 RESEARCH STUDENTS AT BS-SYMESTER LEVEL) D. THESIS SUPERVISED AT M. SC LEVEL SINCE 1997 to 2017. (SUPERVISED SIXTY (70) M. SC THESES IN THE FOLLOWING FIELDS: Research Interest 1. Pharmacognostic study of medicinal plants of Pakistan 2. Antimicrobial activities of medicinal plants of Pakistan 3. Proximate and mineral composition of medicinal plants of Pakistan using SEM and Atomic Absorption spectrophotometer 4. Phytochemical screening of medicinal plants of Pakistan.