Upholding the Australian Constitution Volume 23

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Environment Is All Rights: Human Rights, Constitutional Rights and Environmental Rights

Advance Copy THE ENVIRONMENT IS ALL RIGHTS: HUMAN RIGHTS, CONSTITUTIONAL RIGHTS AND ENVIRONMENTAL RIGHTS RACHEL PEPPER* AND HARRY HOBBS† Te relationship between human rights and environmental rights is increasingly recognised in international and comparative law. Tis article explores that connection by examining the international environmental rights regime and the approaches taken at a domestic level in various countries to constitutionalising environmental protection. It compares these ap- proaches to that in Australia. It fnds that Australian law compares poorly to elsewhere. No express constitutional provision imposing obligations on government to protect the envi- ronment or empowering litigants to compel state action exists, and the potential for draw- ing further constitutional implications appears distant. As the climate emergency escalates, renewed focus on the link between environmental harm and human harm is required, and law and policymakers in Australia are encouraged to build on existing law in developing broader environmental rights protection. CONTENTS I Introduction .................................................................................................................. 2 II Human Rights-Based Environmental Protections ................................................... 8 A International Environmental Rights ............................................................. 8 B Constitutional Environmental Rights ......................................................... 15 1 Express Constitutional Recognition .............................................. -

Environmental Governance (Technical Paper 2, 2017)

ENVIRONMENTAL GOVERNANCE TECHNICAL PAPER 2 The principal contributions to this paper were provided by the following Panel Members: Adjunct Professor Rob Fowler (principal author), with supporting contributions from Murray Wilcox AO QC, Professor Paul Martin, Dr. Cameron Holley and Professor Lee Godden. .About APEEL The Australian Panel of Experts on Environmental Law (APEEL) is comprised of experts with extensive knowledge of, and experience in, environmental law. Its membership includes environmental law practitioners, academics with international standing and a retired judge of the Federal Court. APEEL has developed a blueprint for the next generation of Australian environmental laws with the aim of ensuring a healthy, functioning and resilient environment for generations to come. APEEL’s proposals are for environmental laws that are as transparent, efficient, effective and participatory as possible. A series of technical discussion papers focus on the following themes: 1. The foundations of environmental law 2. Environmental governance 3. Terrestrial biodiversity conservation and natural resources management 4. Marine and coastal issues 5. Climate law 6. Energy regulation 7. The private sector, business law and environmental performance 8. Democracy and the environment The Panel Adjunct Professor Rob Fowler, University of South The Panel acknowledges the expert assistance and Australia – Convenor advice, in its work and deliberations, of: Emeritus Professor David Farrier, University of Wollongong Dr Gerry Bates, University of Sydney -

Year 10 High Court Decisions - Activity

Year 10 High Court Decisions - Activity Commonly known The Franklin Dam Case 1983 name of the case Official legal title Commonwealth v Tasmania ("Tasmanian Dam case") [1983] HCA 21; (1983) 158 CLR 1 (1 July 1983) Who are the parties involved? Key facts - Why did this come to the High Court? Who won the case? What type of verdict was it? What key points did the High Court make in this case? Has there been a change in the law as a result of this decision? What is the name of this law? Recommended 1. Envlaw.com.au. (2019). Environmental Law Australia | Tasmanian Dam Case. [online] Available at: http://envlaw.com.au/tasmanian-dam-case Resources [Accessed 19 Feb. 2019]. 2. High Court of Australia. (2019). Commonwealth v Tasmania ("Tasmanian Dam case") [1983] HCA 21; (1983) 158 CLR 1 (1 July 1983). [online] Available at: http://www7.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/viewdoc/au/cases/cth/HCA/1983/21.html [Accessed 19 Feb. 2019] 3. Aph.gov.au. (2019). Chapter 5 – Parliament of Australia. [online] Available at: https://www.aph.gov.au/parliamentary_business/committees/senate/legal_and_constitutional_affairs/completed_inquiries/pre1996/treaty/report /c05 [Accessed 20 Feb. 2019. GO TO 5. 31 to find details on this case] 1 The Constitutional Centre of Western Australia Updated September 2019 Year 10 High Court Decisions - Activity Commonly known MaboThe Alqudsi Case Case name of the case Official legal title AlqudsiMabo v vQueensland The Queen [2016](No 2) HCA[1992] 24 HCA 23; (1992) 175 CLR 1 (3 June 1992). Who are the parties Whoinvolved? are the parties involved? Key facts - Why did Keythis comefacts -to Why the did thisHigh come Court? to the High Court? Who won the case? Who won the case? What type of verdict Whatwas it? type of verdict wasWhat it? key points did Whatthe High key Court points make did thein this High case? Court make Hasin this there case? been a Haschange there in beenthe law a as changea result inof thethis law as adecision? result of this Whatdecision? is the name of Whatthis law? is the name of Recommendedthis law? 1. -

MDBRC Submission

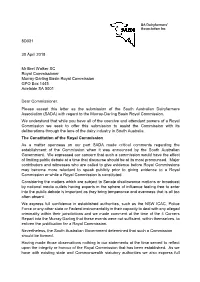

SA Dairyfarmers’ Association Inc 8D031 30 April 2018 Mr Bret Walker SC Royal Commissioner Murray-Darling Basin Royal Commission GPO Box 1445 Adelaide SA 5001 Dear Commissioner, Please accept this letter as the submission of the South Australian Dairyfarmers Association (SADA) with regard to the Murray-Darling Basin Royal Commission. We understand that while you have all of the coercive and attendant powers of a Royal Commission we seek to offer this submission to assist the Commission with its deliberations through the lens of the dairy industry in South Australia. The Constitution of the Royal Commission As a matter openness on our part SADA made critical comments regarding the establishment of the Commission when it was announced by the South Australian Government. We expressed our concern that such a commission would have the effect of limiting public debate at a time that discourse should be at its most pronounced. Major contributors and witnesses who are called to give evidence before Royal Commissions may become more reluctant to speak publicly prior to giving evidence to a Royal Commission or while a Royal Commission is constituted. Considering the matters which are subject to Senate disallowance motions or broadcast by national media outlets having experts in the sphere of influence feeling free to enter into the public debate is important as they bring temperance and evenness that is all too often absent. We express full confidence in established authorities, such as the NSW ICAC, Police Force or any other state or Federal instrumentality in their capacity to deal with any alleged criminality within their jurisdictions and we made comment at the time of the 4 Corners Report into the Murray Darling that these events were not sufficient, within themselves, to enliven the justification for a Royal Commission. -

Victorian Historical Journal

VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL VOLUME 90, NUMBER 2, DECEMBER 2019 ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF VICTORIA VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF VICTORIA The Victorian Historical Journal has been published continuously by the Royal Historical Society of Victoria since 1911. It is a double-blind refereed journal issuing original and previously unpublished scholarly articles on Victorian history, or occasionally on Australian history where it illuminates Victorian history. It is published twice yearly by the Publications Committee; overseen by an Editorial Board; and indexed by Scopus and the Web of Science. It is available in digital and hard copy. https://www.historyvictoria.org.au/publications/victorian-historical-journal/. The Victorian Historical Journal is a part of RHSV membership: https://www. historyvictoria.org.au/membership/become-a-member/ EDITORS Richard Broome and Judith Smart EDITORIAL BOARD OF THE VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL Emeritus Professor Graeme Davison AO, FAHA, FASSA, FFAHA, Sir John Monash Distinguished Professor, Monash University (Chair) https://research.monash.edu/en/persons/graeme-davison Emeritus Professor Richard Broome, FAHA, FRHSV, Department of Archaeology and History, La Trobe University and President of the Royal Historical Society of Victoria Co-editor Victorian Historical Journal https://scholars.latrobe.edu.au/display/rlbroome Associate Professor Kat Ellinghaus, Department of Archaeology and History, La Trobe University https://scholars.latrobe.edu.au/display/kellinghaus Professor Katie Holmes, FASSA, Director, Centre for the Study of the Inland, La Trobe University https://scholars.latrobe.edu.au/display/kbholmes Professor Emerita Marian Quartly, FFAHS, Monash University https://research.monash.edu/en/persons/marian-quartly Professor Andrew May, Department of Historical and Philosophical Studies, University of Melbourne https://www.findanexpert.unimelb.edu.au/display/person13351 Emeritus Professor John Rickard, FAHA, FRHSV, Monash University https://research.monash.edu/en/persons/john-rickard Hon. -

Annual Report 2013 | 2014

Annual Report 2013 | 2014 THE SOVEREIGN HILL MUSEUMS ASSOCIATION i ii Sovereign Hill Annual Report 2013 | 2014 ar 2 Contents President’s Report 07 Chief Executive Officer’s Report 11 Marketing 15 Outdoor Museum 21 Education 31 Gold Museum 39 Narmbool 45 Tributes 49 Special Occasions 50 The Sovereign Hill Foundation 52 Major Sponsors, Grants, Donors & Corporate Members 53 Sovereign Hill Prospectors & Sir Henry Bolte Trust 54 The Sovereign Hill Museums Association 55 Staff 58 Volunteers 59 Financial & Statutory Reports 61 3 Charter PURPOSE Our purpose at Sovereign Hill and the Gold Museum is to inspire an understanding of the significance of the central Victorian gold rushes in Australia’s national story, and at Narmbool of the importance of the land, water and biodiversity in Australia’s future. VALUES Service We will ensure that every visitor’s experience is satisfying, and that their needs are paramount in our decision-making. Respect We will act with respect and free from any form of discrimination in what we say and do towards our colleagues, our visitors, and all with whom we do business; we will respect each other’s dignity and right to privacy; and respect the assets we share in doing our jobs. Safety We will maintain a safe and healthy workplace for all our visitors and for all who work on our sites. Integrity We will act in accordance with international and national codes of ethical practice for museums, including respect for the tangible and intangible heritage we collect, research and interpret; for the primary role of museums as places of life-long learning; and as individuals, work to help and support colleagues, work diligently to complete tasks, and at all times act honestly. -

The Australian Electoral Commission Perspective

Chapter Two Current Issues and Recent Cases on Electoral Law — The Australian Electoral Commission perspective Paul Pirani Before turning to an analysis of recent cases dealing with the Electoral Act 1918 (Cth) (hereafter: the Electoral Act), I need to give a quick outline of exactly what is the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) and its role. What is the Australian Electoral Commission? The AEC conducts elections under a range of legislation. The main role for the AEC is the conduct of federal elections under the Electoral Act and referendums under the Referendum (Machinery Provisions) Act 1984 (Referendum Act). However, in addition, the AEC conducts fee-for-service elections under the authority contained in sections 7A and 7B of the Electoral Act, industrial elections under the Fair Work (Registered Organisations) Act 2009, protected action ballots under the Fair Work Act 2009 and elections for the Torres Strait Regional Authority under the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Regional Authority Act 2005. The AEC itself comprises three persons, the Chairperson (the Honourable Peter Heerey, QC), the non-judicial member (the Chief Statistician, Brian Pink) and the Electoral Commissioner (Ed Killesteyn) (see section 6 of the Electoral Act). The AEC is not a body corporate. As a matter of law, the AEC is not a legal entity that is separate from the Commonwealth of Australia. This means that the AEC is not a body corporate and is unable to sue and be sued or to enter into contracts in its own right. This is despite what was stated in the Commonwealth Parliament in 1983 when major reforms to Australia’s electoral laws took place with the amendments to the Electoral Act to establish the AEC. -

Annual Report Tot the Minister 2006-07

Public Record Office Victoria Annual Report to the Minister 2006–2007 Published by Public Record Office Victoria 99 Shiel Street North Melbourne VIC 3051 Tel (03) 9348 5600 Public Record Office Victoria Annual Report to the Minister 2006–2007 September 2007 © Copyright State of Victoria 2007 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. Also published on www.prov.vic.gov.au. ISSN: 1320-8225 Printed by Ellikon Fine Printers on 50% recycled paper. Cover photo: A 1954 petition concerning the proposed closure of the Ferntree Gully to Gembrook railway line (VPRS 3253/P0 Original Papers Tabled in the Legislative Assembly, unit 1195). 1 Public Record Office Victoria Annual Report to the Minister 2006–2007 A report from the Keeper of Public Records as required under section 21 of the Public Records Act 1973 2 The Hon. Lynne Kosky, MP Minister for the Arts The Honourable Lynne Kosky, MP Minister for the Arts Parliament House Melbourne VIC 3002 Dear Minister I am pleased to present a report on the carrying out of my functions under the Public Records Act for the year ending 30 June 2007. Yours sincerely Justine Heazlewood Director and Keeper of Public Records 30 June 2007 Contents 3 5 Public Record Office Victoria 6 Purpose and Objectives 7 Message from the Director 8 Highlights 2006–2007 12 Public Records Advisory Council 14 Overview 14 Administration 15 Contacts 16 Organisational structure 18 Output measures 2006–2007 19 Leadership – records management -

Parliamentary Debates (Hansard)

PARLIAMENT OF VICTORIA PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL FIFTY-NINTH PARLIAMENT FIRST SESSION WEDNESDAY, 11 NOVEMBER 2020 hansard.parliament.vic.gov.au By authority of the Victorian Government Printer The Governor The Honourable LINDA DESSAU, AC The Lieutenant-Governor The Honourable KEN LAY, AO, APM The ministry Premier........................................................ The Hon. DM Andrews, MP Deputy Premier, Minister for Education and Minister for Mental Health .. The Hon. JA Merlino, MP Minister for Regional Development, Minister for Agriculture and Minister for Resources ........................................ The Hon. J Symes, MLC Minister for Transport Infrastructure and Minister for the Suburban Rail Loop ....................................................... The Hon. JM Allan, MP Minister for Training and Skills and Minister for Higher Education .... The Hon. GA Tierney, MLC Treasurer, Minister for Economic Development and Minister for Industrial Relations ........................................... The Hon. TH Pallas, MP Minister for Public Transport and Minister for Roads and Road Safety . The Hon. BA Carroll, MP Minister for Energy, Environment and Climate Change and Minister for Solar Homes ................................................ The Hon. L D’Ambrosio, MP Minister for Child Protection and Minister for Disability, Ageing and Carers ...................................................... The Hon. LA Donnellan, MP Minister for Health, Minister for Ambulance Services and Minister for Equality ................................................... -

List of Members 46Th Parliament Volume 01 - 20 June 2019

The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia House of Representatives List of Members 46th Parliament Volume 01 - 20 June 2019 No. Name Electorate & Party Electorate office address, telephone, facsimile Parliament House telephone & State / Territory numbers and email address facsimile numbers 1. Albanese, The Hon Anthony Norman Grayndler, ALP 334A Marrickville Road, Marrickville NSW 2204 Tel: (02) 6277 4022 Leader of the Opposition NSW Tel : (02) 9564 3588, Fax : (02) 9564 1734 Fax: (02) 6277 8562 E-mail: [email protected] 2. Alexander, Mr John Gilbert OAM Bennelong, LP 32 Beecroft Road, Epping NSW 2121 Tel: (02) 6277 4804 NSW (PO Box 872, Epping NSW 2121) Fax: (02) 6277 8581 Tel : (02) 9869 4288, Fax : (02) 9869 4833 E-mail: [email protected] 3. Allen, Dr Katie Jane Higgins, LP 1/1343 Malvern Road, Malvern VIC 3144 Tel: (02) 6277 4100 VIC Tel : (03) 9822 4422 Fax: (02) 6277 8408 E-mail: [email protected] 4. Aly, Dr Anne Cowan, ALP Shop 3, Kingsway Shopping Centre, 168 Tel: (02) 6277 4876 WA Wanneroo Road, Madeley WA 6065 Fax: (02) 6277 8526 (PO Box 219, Kingsway WA 6065) Tel : (08) 9409 4517, Fax : (08) 9409 9361 E-mail: [email protected] 5. Andrews, The Hon Karen Lesley McPherson, LNP Ground Floor The Point 47 Watts Drive, Varsity Tel: (02) 6277 7070 Minister for Industry, Science and Technology QLD Lakes QLD 4227 Fax: (02) N/A (PO Box 409, Varsity Lakes QLD 4227) Tel : (07) 5580 9111, Fax : (07) 5580 9700 E-mail: [email protected] 6. -

Life Education NSW 2016-2017 Annual Report I Have Fond Memories of the Friendly, Knowledgeable Giraffe

Life Education NSW 2016-2017 Annual Report I have fond memories of the friendly, knowledgeable giraffe. Harold takes you on a magical journey exploring and learning about healthy eating, our body - how it works and ways we can be active in order to stay happy and healthy. It gives me such joy to see how excited my daughter is to visit Harold and know that it will be an experience that will stay with her too. Melanie, parent, Turramurra Public School What’s inside Who we are 03 Our year Life Education is the nation’s largest not-for-profit provider of childhood preventative drug and health education. For 06 Our programs almost 40 years, we have taken our mobile learning centres and famous mascot – ‘Healthy Harold’, the giraffe – to 13 Our community schools, teaching students about healthy choices in the areas of drugs and alcohol, cybersafety, nutrition, lifestyle 25 Our people and respectful relationships. 32 Our financials OUR MISSION Empowering our children and young people to make safer and healthier choices through education. OUR VISION Generations of healthy young Australians living to their full potential. LIFE EDUCATION NSW 2016-2017 Annual Report Our year: Thank you for being part of Life Education NSW Together we worked to empower more children in NSW As a charity, we’re grateful for the generous support of the NSW Ministry of Health, and the additional funds provided by our corporate and community partners and donors. We thank you for helping us to empower more children in NSW this year to make good life choices. -

The Effect of Poverty and Politics on the Development of Tasmanian

THE EFFECT OF POVERTY AND POLITICS ON THE DEVELOPMENT . OF TASMANIAN STATE EDUCATION. .1.900 - 1950 by D.V.Selth, B.A., Dip.Ed. Admin. submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. UNIVERSITi OF TASMANIA HOBART 1969 /-4 This thesis contains no material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma in any university and, to the best of my knowledge and belief, contains no copy or paraphrase of material previously published or written by another person, except when due reference is made in the text of the thesis. 0 / la D.V.Selth. STATEMENT OF THESIS Few Tasmanians believed education was important in the early years of the twnntieth century, and poverty and conservatism were the most influential forces in society. There was no public pressure to compel politicians to assist the development of education in the State, or to support members of the profession who endeavoured to do so. As a result 7education in Tasmania has been more influenced by politics than by matters of professionL1 concern, and in turn the politicians have been more influenced'by the state of the economy than the needs of the children. Educational leadership was often unproductive because of the lack of political support, and political leadership was not fully productive because its aims were political rather than educational. Poverty and conservatism led to frustration that caused qualified and enthusiastic young teachers to seek higher salaries and a more congenial atmosphere elsewhere, and also created bitterness and resentment of those who were able to implement educational policies, with less dependence , on the state of the economy or the mood of Parliament.