James Britton Ii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Lowe Family Circle

THE ANCESTORS OF THE JOHN LOWE FAMILY CIRCLE AND THEIR DESCENDANTS FITCHBURG PRINTED BY THE SENTINEL PRINTING COMPANY 1901 INTRODUCTION. Previous to the year 1891 our family had held a pic nic on the Fourth of July for twenty years or more, but the Fourth of July, 1890, it was suggested· that we form what vvas named " The John Lowe Family Circle." The record of the action taken at that time is as follows: FITCHBURG, July 5, 1890. For the better promotion and preservation of our family interests, together with a view to holding an annual gathering, we, the sons and daughters of John Lowe, believing that these ends will be better accom plished hy an organization, hereby subscribe to the fol lowing, viz.: The organization shall be called the "JOHN LO¥lE :FAMILY," and the original officers shall be: President, Waldo. Secretary, Ellen. Treasurer, "I..,ulu." Committee of Research, Edna, Herbert .. and David; and the above officers are expected to submit a constitu- tion and by-laws to a gathering to be held the coming winter. Arthur H. Lo\\re, Albert N. Lowe, Annie P. Lowe, Emma P. Lowe, Mary V. Lowe, Ira A. Lowe, Herbert G. Lowe, Annie S. Lowe, 4 I ntroducti'on. • Waldo H. Lowe, J. E. Putnam, Mary L. Lowe, L. W. Merriam, Orin M. Lowe, Ellen M. L. Merriam, Florence Webber Lowe, David Lowe, Lewis M. Lowe, Harriet L. Lowe, " Lulu " W. Lowe. Samuel H. Lowe, George R. Lowe, John A. Lowe, Mary E. Lowe, Marian A·. Lowe, Frank E. Lowe, Ezra J. Riggs, Edna Lowe Putnam, Ida L. -

History's Future

Winter 2003 ture the multigenera- American and East Asian history, to tional change that name a few. Recent faculty publica- shapes the Los tions span topics from the history of Angeles immigrant household government in America to communities. Down the study of medieval women. the corridor, Philip “The momentum of the history Ethington documents department is being fueled by some the timeless transfor- outstanding new faculty members, a mation of Los Angeles’ growing list of external collaborations people, landscapes and and the smart use of technology,” architecture through says College Dean Joseph Aoun. streaming media and “We are positioned to do some great digital panoramic pho- things in the 21st century.” tos. Meanwhile, medievalist Lisa Tales of the West Bitel—a recent The College boasts a strong con- Guggenheim Fellow— figuration of late 19th- and early collaborates with 20th-century American historians, scholars in European and is a pre-eminent center for libraries in a quest to examining the American West. make archives that At the forefront is University detail women’s first Professor and California State religious communities Librarian Kevin Starr, whose book easily accessible via the series chronicling California history Internet. Another col- and the American dream has gained league, Steven Ross, worldwide popularity. partners with the USC Other historians, such as Sanchez Center for Scholarly and Lon Kurashige, study Latino and Technology to docu- Asian immigration patterns to better ment how film shaped understand how American society has ideas about class and organized and changed through time. power in the 20th cen- Indeed, the College’s prime urban tury. -

Джоð½ Зоñ€Ð½ ÐлÐ

Джон Зорн ÐÐ »Ð±ÑƒÐ¼ ÑÐ ¿Ð¸ÑÑ ŠÐº (Ð ´Ð¸ÑÐ ºÐ¾Ð³Ñ€Ð°Ñ„иÑÑ ‚а & график) The Big Gundown https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-big-gundown-849633/songs Spy vs Spy https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/spy-vs-spy-249882/songs Buck Jam Tonic https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/buck-jam-tonic-2927453/songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/six-litanies-for-heliogabalus- Six Litanies for Heliogabalus 3485596/songs Late Works https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/late-works-3218450/songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/templars%3A-in-sacred-blood- Templars: In Sacred Blood 3493947/songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/moonchild%3A-songs-without-words- Moonchild: Songs Without Words 3323574/songs The Crucible https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-crucible-966286/songs Ipsissimus https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/ipsissimus-3154239/songs The Concealed https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-concealed-1825565/songs Spillane https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/spillane-847460/songs Mount Analogue https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/mount-analogue-3326006/songs Locus Solus https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/locus-solus-3257777/songs https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/at-the-gates-of-paradise- At the Gates of Paradise 2868730/songs Ganryu Island https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/ganryu-island-3095196/songs The Mysteries https://bg.listvote.com/lists/music/albums/the-mysteries-15077054/songs A Vision in Blakelight -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1986

Іі$Ье(і by the Ukrainian National Association Inc., a fraternal non-profit association! ШrainianWeekl v ; Vol. LIV No. 34 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, AUGUST 24, 1986 25 cents Clandestine sources dispute Israel indirectly approaches USSR official Chornobyl information for help in Demjanjuk prosecution ELLICOTT CITY, Md. — The first For unexplained reasons, foreign JERSEY CITY, N.J. — Israeli offi- The card, which was used in the samvydav information has reached the radio broadcasts were difficult to pick cials have reportedly indirectly ap- United States by the Office of Special West about the accident at the Chor- up and understand within a 30-kilo- proached the Soviet Union for assis- Investigations in its proceedings against nobyl nuclear power plant in Ukraine in meter radius of the Chornobyl plant. tance in their case against John Dem- Mr. Demjanjuk, has been the subject of late April. This information disputes Thus, many listeners could not take ad- janjuk, the former Cleveland auto- much controversy. The Demjanjuk many pronouncements by the Soviet vantage of the news and advice broad- worker suspected of being "Ivan the defense contends it is a fraud and that government, reported Smoloskyp, a cast from abroad. Terrible," a guard at the Treblinka there is evidence the card was altered. quarterly published here. Although tens of thousands of death camp known for his brutality. In fact, Mark O'Connor, Mr. Dem- Following is Smoloskyp's story on school-age children were sent from Kiev The Jerusalem Post reported on janjuk's lawyer, had told The Weekly the new samvydav information. to camps on the Black Sea early, pre- August 18 that State Attorney Yona earlier this year that the original ID card According to these underground school children — who are most threat- Blattman had reportedly asked an was never examined by forensic experts. -

Six Canonical Projects by Rem Koolhaas

5 Six Canonical Projects by Rem Koolhaas has been part of the international avant-garde since the nineteen-seventies and has been named the Pritzker Rem Koolhaas Architecture Prize for the year 2000. This book, which builds on six canonical projects, traces the discursive practice analyse behind the design methods used by Koolhaas and his office + OMA. It uncovers recurring key themes—such as wall, void, tur montage, trajectory, infrastructure, and shape—that have tek structured this design discourse over the span of Koolhaas’s Essays on the History of Ideas oeuvre. The book moves beyond the six core pieces, as well: It explores how these identified thematic design principles archi manifest in other works by Koolhaas as both practical re- Ingrid Böck applications and further elaborations. In addition to Koolhaas’s individual genius, these textual and material layers are accounted for shaping the very context of his work’s relevance. By comparing the design principles with relevant concepts from the architectural Zeitgeist in which OMA has operated, the study moves beyond its specific subject—Rem Koolhaas—and provides novel insight into the broader history of architectural ideas. Ingrid Böck is a researcher at the Institute of Architectural Theory, Art History and Cultural Studies at the Graz Ingrid Böck University of Technology, Austria. “Despite the prominence and notoriety of Rem Koolhaas … there is not a single piece of scholarly writing coming close to the … length, to the intensity, or to the methodological rigor found in the manuscript -

An Anthropological Exploration of the Effects of Family Cash Transfers On

AN ANTHROPOLOGICAL EXPLORATION OF THE EFFECTS OF FAMILY CASH TRANSFERS ON THE DIETS OF MOTHERS AND CHILDREN IN THE BRAZILIAN AMAZON Ana Carolina Barbosa de Lima Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Anthropology, Indiana University July, 2017 Accepted by the Graduate Faculty, Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy. Doctoral Committee ________________________________ Eduardo S. Brondízio, PhD ________________________________ Catherine Tucker, PhD ________________________________ Darna L. Dufour, PhD ________________________________ Richard R. Wilk, PhD ________________________________ Stacey Giroux Wells, PhD Date of Defense: April 14th, 2017. ii AKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost, I would like to thank my research committee. I have immense gratitude and admiration for my main adviser, Eduardo Brondízio, who has been present and supportive throughout the development of this dissertation as a mentor, critic, reviewer, and friend. Richard Wilk has been a source of inspiration and encouragement since the first stages of this work, someone who never doubted my academic capacity and improvement. Darna Dufour generously received me in her lab upon my arrival from fieldwork, giving precious advice on writing, and much needed expert guidance during a long year of dietary and anthropometric data entry and analysis. Catherine Tucker was on board and excited with my research from the very beginning, and carefully reviewed the original manuscript. Stacey Giroux shared her experience in our many meetings in the IU Center for Survey Research, and provided rigorous feedback. I feel privileged to have worked with this set of brilliant and committed academics. -

Long, Long Ago / by Clara C. Lenroot

Library of Congress Long, long ago / by Clara C. Lenroot Clara C. Lenroot Long, Long Ago by Mrs. Clara C lough . Lenroot Badger-Printing-Co. Appleton, Wisconsin PRINTED IN U. S. A. 1929 To my dear sister Bertha, who shares most of these memories with me, they are affectionately dedicated. THE LITTLE GIRL I USED TO BE The little girl I used to be Has come to-day to visit me. She wears her Sunday dress again — Merino, trimmed with gay delaine; Bare neck and shoulders, bare arms, too, Short sleeves caught up with knots of blue; Cunning black shoes, and stockings white, And ruffled pantelettes in sight. Her hair, ‘round Mother's finger curled, Looks “natural” for all the world! The little girl I used to be! So wistfully she looks at me! O, poignant is my heart's regret That ever I have failed her! yet, Something of her has come with me Along the years that used to be! I pray that when ‘tis time to go Away from all the life we know To the new life, where, free from sin, As little children we begin, This little girl I used to be Will still be here to go with me! —C. C. L. 1 LONG, LONG AGO Tell me the tales that to me were so dear, Long, long ago; long, long ago. Sing me the songs I delighted to hear, Long, long ago, long ago. F. H. Bayley HUDSON Long, long ago / by Clara C. Lenroot http://www.loc.gov/resource/lhbum.09423 Library of Congress In the year 1861 there lived in a little backwoods town of Wisconsin a family with which this narrative has much to do. -

The Book of Lies Falsely :So Called

LIBER CCCXXXIII THE BOOK OF LIES FALSELY :SO CALLED (c) Ordo Templi Orientis. First published London: E.J. Wieland, 1913. Second edition with commentary Ilfracombe: Haydn Press, 1952 This electronic edition created by Celephaïs Press somewhere beyond the Tanarian Hills Original key entry by Frater E.A.D.N. Formatting and some further proof reading by Frater T.S. THE BOOK OF LIES WHICH IS ALSO FALSELY CALLED BREAKS THE WANDERINGS OR FALSIFICATIONS OF THE ONE THOUGHT OF FRATER PERDURABO (Aleister Crowley) WHICH THOUGHT IS ITSELF UNTRUE A REPRINT with an additional commentary to each chapter. “Break, break, break At the foot of thy stones, O Sea ! And I would that I could utter The thoughts that arise in me! COMMENTARY (Title Page) The number of the book is 333, as implying dis-persion, so as to correspond with the title, “Breaks” and “Lies”. However, the “one thought is itself untrue”, and therefore its falsifications are relatively true. This book therefore consists of statements as nearly true as is possible to human language. The verse from Tennyson is inserted partly because of the pun on the word “break”; partly because of the reference to the meaning of this title page, as explained above; partly because it is intensely amusing for Crowley to quote Tennyson. There is no joke or subtle meaning in the publisher’s imprint. V A\A\ Publication in Class C and D Official for the Grade of Babe of the Abyss ? ! KEFALH H OUK ESTI KEFALH O!1 THE ANTE PRIMAL TRIAD WHICH IS NOT-GOD Nothing is. -

The Autobiography of Patience Loader Rozsa Archer

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All USU Press Publications USU Press 2006 Recollections of Past Days: The Autobiography of Patience Loader Rozsa Archer Sandra Ailey Petree Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/usupress_pubs Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Archer, P. L., & Petree, S. A. (2006). Recollections of past days: The autobiography of Patience Loader Rozsa Archer. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the USU Press at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All USU Press Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recollections of Past Days The Autobiography of PATIENCE LOADER ROZSA ARCHER Edited by Sandra Ailey Petree Recollections of Past Days The Autobiography of Patience Loader Rozsa Archer Volume 8 Life Writings of Frontier Women A Series Edited by Maureen Ursenbach Beecher Volume 1 Winter Quarters The 1846 –1848 Life Writings of Mary Haskin Parker Richards Edited by Maurine Carr Ward Volume 2 Mormon Midwife The 1846 –1888 Diaries of Patty Bartlett Sessions Edited by Donna Toland Smart Volume 3 The History of Louisa Barnes Pratt Being the Autobiography of a Mormon Missionary Widow and Pioneer Edited by S. George Ellsworth Volume 4 Out of the Black Patch The Autobiography of Effi e Marquess Carmack Folk Musician, Artist, and Writer Edited by Noel A. Carmack and Karen Lynn Davidson Volume 5 The Personal Writings of Eliza Roxcy Snow Edited by Maureen Ursenbach Beecher Volume 6 A Widow’s Tale The 1884–1896 Diary of Helen Mar Kimball Whitney Transcribed and Edited by Charles M. -

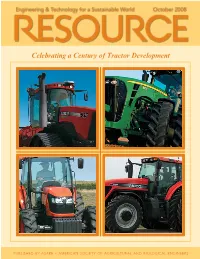

Resource Magazine October 2008 Engineering and Technology for A

Engineering & Technology for a Sustainable World October 2008 Celebrating a Century of Tractor Development PUBLISHED BY ASABE – AMERICAN SOCIETY OF AGRICULTURAL AND BIOLOGICAL ENGINEERS Targeted access to 9,000 international agricultural & biological engineers Ray Goodwin (800) 369-6220, ext. 3459 BIOH0308Filler.indd 1 7/24/08 9:15:05 PM FEATURES COVER STORY 5 Celebrating a Century of Tractor Development Carroll Goering Engineering & Technology for a Sustainable World October 2008 Plowing down memory lane: a top-six list of tractor changes over the last century with emphasis on those that transformed agriculture. Vol. 15, No. 7, ISSN 1076-3333 7 Adding Value to Poultry Litter Using ASABE President Jim Dooley, Forest Concepts, LLC Transportable Pyrolysis ASABE Executive Director M. Melissa Moore Foster A. Agblevor ASABE Staff “This technology will not only solve waste disposal and water pollution Publisher Donna Hull problems, it will also convert a potential waste to high-value products such as Managing Editor Sue Mitrovich energy and fertilizer.” Consultants Listings Sandy Rutter Professional Opportunities Listings Melissa Miller ENERGY ISSUES, FOURTH IN THE SERIES ASABE Editorial Board Chair Suranjan Panigrahi, North Dakota State University 9 Renewable Energy Gains Global Momentum Secretary/Vice Chair Rafael Garcia, USDA-ARS James R. Fischer, Gale A. Buchanan, Ray Orbach, Reno L. Harnish III, Past Chair Edward Martin, University of Arizona and Puru Jena Board Members Wayne Coates, University of Arizona; WIREC 2008 brought together world leaders in the fi eld of renewable energy Jeremiah Davis, Mississippi State University; from 125 countries to address the market adoption and scale-up of renewable Donald Edwards, retired; Mark Riley, University of Arizona; Brian Steward, Iowa State University; energy technologies. -

An Improbable Venture

AN IMPROBABLE VENTURE A HISTORY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO NANCY SCOTT ANDERSON THE UCSD PRESS LA JOLLA, CALIFORNIA © 1993 by The Regents of the University of California and Nancy Scott Anderson All rights reserved. Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Anderson, Nancy Scott. An improbable venture: a history of the University of California, San Diego/ Nancy Scott Anderson 302 p. (not including index) Includes bibliographical references (p. 263-302) and index 1. University of California, San Diego—History. 2. Universities and colleges—California—San Diego. I. University of California, San Diego LD781.S2A65 1993 93-61345 Text typeset in 10/14 pt. Goudy by Prepress Services, University of California, San Diego. Printed and bound by Graphics and Reproduction Services, University of California, San Diego. Cover designed by the Publications Office of University Communications, University of California, San Diego. CONTENTS Foreword.................................................................................................................i Preface.........................................................................................................................v Introduction: The Model and Its Mechanism ............................................................... 1 Chapter One: Ocean Origins ...................................................................................... 15 Chapter Two: A Cathedral on a Bluff ......................................................................... 37 Chapter Three: -

Digital Collections at the University of the Arts

The UniversiT y of The ArTs Non Profit Org 320 South Broad Street US Postage Philadelphia, PA 19102 PAID www.UArts.edu Philadelphia, PA Permit No. 1103 THE MAGAZINE OF The UniversiT y of The ArTs edg e THE edge MAGAZINE OF T he U niver si T y of T he A r T s WINTER WINTER 2013 2013 NO . 9 Edge9_Cover_FINAL.crw4.indd 1 1/22/13 12:50 PM THE from PRESIDENT A decade has passed since the publication In this issue of Edge, we examine the book’s of Richard Florida’s international bestseller theses and arguments a decade on, and The Rise of the Creative Class. This 10-year speak with a range of experts both on and of anniversary provides an opportunity to ex- the creative class, including Richard Florida amine the impact of that seminal work and himself. I think you will find their insights the accuracy of its predictions, some of them and perspectives quite interesting. bold. The book’s subtitle—“...And How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community, Following on the theme of the power of and Everyday Life”—speaks to the profes- creatives, we also look at the creative econ- sor and urban-studies specialist’s vision of omy of the Philadelphia region and the far- the impact this creative sector can exert on reaching impact that University of the Arts virtually all aspects of our lives. alumni and faculty have on it. You will also find features on UArts students, alumni and Since its 2002 release, many of the ap- faculty who are forging innovative entrepre- proaches to urban regeneration proposed neurial paths of their own.