Long, Long Ago / by Clara C. Lenroot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Lowe Family Circle

THE ANCESTORS OF THE JOHN LOWE FAMILY CIRCLE AND THEIR DESCENDANTS FITCHBURG PRINTED BY THE SENTINEL PRINTING COMPANY 1901 INTRODUCTION. Previous to the year 1891 our family had held a pic nic on the Fourth of July for twenty years or more, but the Fourth of July, 1890, it was suggested· that we form what vvas named " The John Lowe Family Circle." The record of the action taken at that time is as follows: FITCHBURG, July 5, 1890. For the better promotion and preservation of our family interests, together with a view to holding an annual gathering, we, the sons and daughters of John Lowe, believing that these ends will be better accom plished hy an organization, hereby subscribe to the fol lowing, viz.: The organization shall be called the "JOHN LO¥lE :FAMILY," and the original officers shall be: President, Waldo. Secretary, Ellen. Treasurer, "I..,ulu." Committee of Research, Edna, Herbert .. and David; and the above officers are expected to submit a constitu- tion and by-laws to a gathering to be held the coming winter. Arthur H. Lo\\re, Albert N. Lowe, Annie P. Lowe, Emma P. Lowe, Mary V. Lowe, Ira A. Lowe, Herbert G. Lowe, Annie S. Lowe, 4 I ntroducti'on. • Waldo H. Lowe, J. E. Putnam, Mary L. Lowe, L. W. Merriam, Orin M. Lowe, Ellen M. L. Merriam, Florence Webber Lowe, David Lowe, Lewis M. Lowe, Harriet L. Lowe, " Lulu " W. Lowe. Samuel H. Lowe, George R. Lowe, John A. Lowe, Mary E. Lowe, Marian A·. Lowe, Frank E. Lowe, Ezra J. Riggs, Edna Lowe Putnam, Ida L. -

Vol. 3, Spring 2001

The University of Iowa School of ArtNEWSLETTER &History Volume 3 Spring/Summer 2001 Art Greetings Warm greetings from the School of Art and Adams, who taught contemporary African Art History! After one of the coldest and art with us this spring will be joining us from harshest winters on record here we as an assistant professor of art history this enjoyed a magnificent spring (although we fall. Over the next few weeks we expect Dorothy are all keeping an eye on the river which to add a faculty member in graphic design is getting higher every day). As the and several visitors in art and art history Johnson, spring semester draws to a close we are for the next academic year. looking forward to the M.F.A. show in the Director Museum of Art and are still enjoying the Growth & Development faculty show at the Museum which is one The School continues to grow every year. of the largest and most diverse we have The numbers of our faculty members seen. This year, thanks to the generosity increase as we try to keep up with ever- of the College, the Vice President for growing enrollments at the undergraduate Research and the University Foundation, and graduate levels. This year we have we are going to have a catalogue of the well over 700 undergraduate majors and faculty exhibit in full color. over 200 graduate students. In addition, we serve thousands of non-majors, espe- Farewells cially in our General Education classes in This is also the time of year for farewells. -

King George and the Royal Family

ICO = 00 100 :LD = 00 CD "CO KING GEORGE AND THE ROYAL FAMILY KING GEORGK V Bust by Alfred Drury, K.A. &y permission of the sculptor KING GEORGE j* K AND THE ROYAL FAMILY y ;' ,* % j&i ?**? BY EDWARD LEGGE AUTHOR OF 'KING EDWARD IN HIS TRUE COLOURS' VOLUME I LONDON GRANT RICHARDS LTD. ST. MARTIN'S STREET MCMXVIII " . tjg. _^j_ $r .ffft* - i ' JO^ > ' < DA V.I PRINTED IN OBEAT BRITAIN AT THE COMPLETE PRESS WEST NORWOOD LONDON CONTENTS CHAP. PAQB I. THE KING'S CHARACTER AND ATTRIBUTES : HIS ACCESSION AND " DECLARATION " 9 II. THE QUEEN 55 " III. THE KING BETWEEN THE DEVIL AND THE DEEP SEA" 77 IV. THE INTENDED COERCION OF ULSTER 99 V. THE KING FALSELY ACCUSED OF " INTER- VENTION " 118 VI. THE MANTLE OF EDWARD VII INHERITED BY GEORGE V 122 VII. KING GEORGE AND QUEEN MARY IN PARIS (1914) 138 VIII. THE KING'S GREAT ADVENTURE (1914) 172 IX. THE MISHAP TO THE KING IN FRANCE, 1915 180 X. THE KING'S OWN WORDS 192 XI. WHY THE SOVEREIGNS ARE POPULAR 254 XII. THE KING ABOLISHES GERMAN TITLES, AND FOUNDS THE ROYAL HOUSE AND FAMILY OF WINDSOR 286 " XIII. " LE ROY LE VEULT 816 XIV. KING GEORGE, THE KAISER, HENRY THE SPY, AND MR. GERARD : THE KING'S TELE- GRAMS, AND OTHERS 827 f 6 CONTENTS CHAP. PAGE XV. KING GEORGE'S PARENTS IN PARIS 841 XVI. THE GREATEST OF THE GREAT GARDEN PARTIES 347 XVII. THE KING'S ACTIVITIES OUTLINED : 1910-1917 356 XVIII. THE CORONATION 372 ILLUSTRATIONS To face page KING GEORGE V Frontispiece His LATE MAJESTY KING EDWARD VII 40 PORTRAIT OF THE LATE PRINCESS MARY OF CAMBRIDGE 56 THE CHILDREN OF THE ROYAL FAMILY 74 THE KING AND QUEEN AT THE AMERICAN OFFICERS' CLUB, MAYFAIR 122 THE KING AND PRESIDENT POINCARE 138 THE QUEEN AND MADAME POINCARE 158 " HAPPY," THE KING'S DOG 176 A LUNCHEON PARTY AT SANDRINGHAM 190 His MAJESTY KING GEORGE V IN BRITISH FIELD-MARSHAL'S UNIFORM 226 FACSIMILES OF CHRISTMAS CARDS 268 H.R.H. -

ENGLISH OPINIONS on the FRENCH REVOLUTION by W. T. WAGONER Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University Of

ENGLISH OPINIONS ON THE FRENCH REVOLUTION By W. T. WAGONER Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT ARLINGTON May 2009 Copyright © by W.T. Wagoner 2008 All Rights Reserved ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the University of Texas at Arlington for employing the faculty and providing the facilities that made my education such a memorable experience. I would like to give a special note of appreciation to the professors of my committee, Dr. Reinhardt, Dr. Cawthon and Dr.Narrett who have shown extraordinary patience and kindness in helping me find my voice and confidence during this process. I appreciate my family and friends who tolerated both my mood swings and my forgetfulness as I thought about events hundreds of years ago. I would like to thank my mother. You encouraged me that there was more to life than flooring. To my wife, Rae, I want to thank you for loving me and keeping me centered. Finally, to my daughter Miranda, you are the reason I have undertaken this journey. December 20, 2008 iii ABSTRACT ENGLISH WORDS ON THE FRENCH REVOLUTION W.T. WAGONER, M.A. The University of Texas at Arlington, 2008 Supervising Professor: Steven Reinhardt Just as the French Revolution changed the French political landscape, it also affected other European countries such as England. Both pro-revolutionaries and anti-revolutionaries argued in the public forums the merits of the events in France. -

A Comparison of Edmund Burke's Conservatism with the Views of Five Conservative, Academic Judges

University of Miami Law Review Volume 40 Number 4 Article 3 5-1-1986 Justice Diffused: A Comparison of Edmund Burke's Conservatism with the Views of Five Conservative, Academic Judges James G. Wilson Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umlr Recommended Citation James G. Wilson, Justice Diffused: A Comparison of Edmund Burke's Conservatism with the Views of Five Conservative, Academic Judges, 40 U. Miami L. Rev. 913 (1986) Available at: https://repository.law.miami.edu/umlr/vol40/iss4/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Miami Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Miami School of Law Institutional Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Justice Diffused: A Comparison of Edmund Burke's Conservatism with the Views of Five Conservative, Academic Judges JAMES G. WILSON* The author evaluates the constitutionaljurisprudence ofjudges Posner, Bork, Easterbrook, Scalia, and Winter by contrastingtheir views with the political theory of noted conservative Edmund Burke. These judges' conception of politics, legitimacy, separation ofpowers, and tyranny differ significantlyfrom Burke's views, thereby raising questions about the nature of these jurists' conservatism. On June 17, 1986, after this article went to press, Chief Justice Burger resignedfrom the Supreme Court. President Reagan nomi- nated Justice Rehnquist as the sixteenth Chief Justice, and Judge Scalia as Justice Rehnquist's successor. I. INTRODUCTION ....................................................... 913 II. THE COMPLEX POLITICS OF EDMUND BURKE ............................ 917 A . -

National Park Service Cultural Landscapes Inventory Marconi

National Park Service Cultural Landscapes Inventory 2007 Marconi Memorial, US Reservation 309 A Rock Creek Park - DC Street Plan Reservations Table of Contents Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan Concurrence Status Geographic Information and Location Map Management Information National Register Information Chronology & Physical History Analysis & Evaluation of Integrity Condition Treatment Bibliography & Supplemental Information Marconi Memorial, US Reservation 309 A Rock Creek Park - DC Street Plan Reservations Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan Inventory Summary The Cultural Landscapes Inventory Overview: CLI General Information: Purpose and Goals of the CLI The Cultural Landscapes Inventory (CLI), a comprehensive inventory of all cultural landscapes in the national park system, is one of the most ambitious initiatives of the National Park Service (NPS) Park Cultural Landscapes Program. The CLI is an evaluated inventory of all landscapes having historical significance that are listed on or eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places, or are otherwise managed as cultural resources through a public planning process and in which the NPS has or plans to acquire any legal interest. The CLI identifies and documents each landscape’s location, size, physical development, condition, landscape characteristics, character-defining features, as well as other valuable information useful to park management. Cultural landscapes become approved CLIs when concurrence with the findings is obtained from the park superintendent and all required data fields are entered into a national database. In addition, for landscapes that are not currently listed on the National Register and/or do not have adequate documentation, concurrence is required from the State Historic Preservation Officer or the Keeper of the National Register. -

THE TRUTH and MEANING of HUMAN SEXUALITY Guidelines For

THE TRUTH AND MEANING OF HUMAN SEXUALITY Guidelines for Education within the Family 8 December 1995 INTRODUCTION The Situation and the Problem 1. Among the many difficulties parents encounter today, despite different social contexts, one certainly stands out: giving children an adequate preparation for adult life, particularly with regard to education in the true meaning of sexuality. There are many reasons for this difficulty and not all of them are new. In the past, even when the family did not provide specific sexual education, the general culture was permeated by respect for fundamental values and hence served to protect and maintain them. In the greater part of society, both in developed and developing countries, the decline of traditional models has left children deprived of consistent and positive guidance, while parents find themselves unprepared to provide adequate answers. This new context is made worse by what we observe: an eclipse of the truth about man which, among other things, exerts pressure to reduce sex to something commonplace. In this area, society and the mass media most of the time provide depersonalized, recreational and often pessimistic information. Moreover, this information does not take into account the different stages of formation and development of children and young people, and it is influenced by a distorted individualistic concept of freedom, in an ambience lacking the basic values of life, human love and the family. Then the school, making itself available to carry out programmes of sex education, has often done this by taking the place of the family and, most of the time, with the aim of only providing information. -

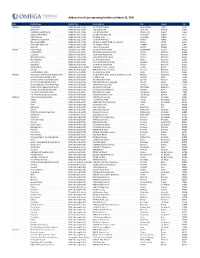

Facilities List for Website.Xlsx

Address list of Core operating facilities at March 31, 2021 State Facility Name Facility Type Street Address City County Zip Alabama Avalon Place Skilled Nursing Facility 200 Alabama Avenue Muscle Shoals Colbert 35661 Brookshire Skilled Nursing Facility 4320 Judith Lane Huntsville Madison 35805 Canterbury Health Center Skilled Nursing Facility 1720 Knowles Road Phoenix City Russell 36867 Cottage of the Shoals Skilled Nursing Facility 500 John Aldridge Drive Tuscumbia Colbert 35674 Keller Landing Skilled Nursing Facility 813 Keller Lane Tuscumbia Colbert 35674 Lynwood Nursing Home Skilled Nursing Facility 4164 Halls Mill Road Mobile Mobile 36693 Merrywood Lodge Skilled Nursing Facility 280 Mount Hebron Road, P.O. Box 130 Elmore Elmore 36025 Northside Health Care Skilled Nursing Facility 700 Hutchins Avenue Gadsden Etowah 35901 River City Skilled Nursing Facility 1350 14th Avenue SE Decatur Morgan 35601 Arizona Austin House Assisted Living Facility 195 South Willard Street Cottonwood Yavapai 86326 Encanto Palms Assisted Living Facility 3901 West Encanto Boulevard Phoenix Maricopa 85009 L'Estancia Skilled Nursing Facility 15810 South 42nd Street Phoenix Maricopa 85048 Maryland Gardens Skilled Nursing Facility 31 West Maryland Avenue Phoenix Maricopa 85013 Mesa Christian Skilled Nursing Facility 255 West Brown Road Mesa Maricopa 85201 Palm Valley Skilled Nursing Facility 13575 West McDowell Road Goodyear Maricopa 85338 Ridgecrest Skilled Nursing Facility 16640 North 38th Street Phoenix Maricopa 85032 Santa Catalina Independent Living Facility -

Colonial Families and Their Descendants

M= w= VI= Z^r (A in Id v o>i ff (9 VV- I I = IL S o 0 00= a iv a «o = I] S !? v 0. X »*E **E *»= 6» = »*5= COLONIAL FAMILIES AND THEIR DESCENDANTS . BY ONE OF THE OLDEST GRADUATES OF ST. MARY'S HALL/BURLI^G-TiON-K.NlfJ.fl*f.'< " The first female Church-School established In '*>fOn|tSe<|;, rSJatesi-, which has reached its sixty-firstyear, and canj'pwß^vwffit-^'" pride to nearly one thousand graduates. ; founder being the great Bishop "ofBishop's^, ¦* -¦ ; ;% : GEORGE WASHINGTON .DOANE;-D^D];:)a:i-B?':i^| BALTIMORE: * PRESS :OF THE.SUN PRINTING OFFICE, ¦ -:- - -"- '-** - '__. -1900. -_ COLONIAL FAMILIES AND THEIR DESCENDANTS , BY ONE OF THE OLDEST GRADUATES OF - ST. MARY'S HALL, BURLINGTON, N. J. " The first female Church-School established in the United.States, which has reached its sixty-first year, and can point with ; pride to nearly one thousand graduates. Its.noble „* _ founder being the great Bishop ofBishops," GEORGE WASHINGTON DOANE, D.D., LL.D: :l BALTIMORE: PRESS "OF THE SUN PRINTING OFFICE, igOO. Dedication, .*«•« CTHIS BOOK is affectionately and respectfully dedicated to the memory of the Wright family of Maryland and South America, and to their descendants now livingwho inherit the noble virtues of their forefathers, and are a bright example to "all"for the same purity of character "they"possessed. Those noble men and women are now in sweet repose, their example a beacon light to those who "survive" them, guiding them on in the path of "usefulness and honor," " 'Tis mine the withered floweret most to prize, To mourn the -

COVID-19 Vaccine Weekly Update

Ramona Whittington From: Roxana Cruz Sent: Tuesday, March 9, 2021 4:52 PM To: Medical Directors; Dental Directors; [email protected]; [email protected]; Myrta Garcia; Lindsay Lanagan; catherine.threatt; Abby Villafane; [email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]; Dr Flower Cc: Jana Eubank; Daniel Diaz; Shelby Tracy; Nancy Gilliam; Ramona Whittington; ClinicalTeam Subject: COVID Vaccine Weekly Update: Week 13 (03/08/2021) Attachments: VaccineToolkit_1pger.pdf; COVIDVaccineAllocation-Week13_FQHCs.pdf; Vaccine Updates 03.09.2021.pdf; jama_moore_2021_vp_210037_1614808773.38942.pdf Dear Fellow CMOs and Vaccine Coordinators, Here is your COVID‐19 Vaccine Updates for Week 13 DSHS Allocations (03‐08‐2021)‐ see attached DSHS list This week 100 Health Center sites were allocated 19,100 vaccines To date (through Week 13), Texas Health Center sites have been allocated a total of 124,100 doses Week Week 1 Week 2 Week 3 Week 4 Week 5 Week 7 Week 8 Week 9 Week 10 Week 11 6 9,900 600 7,500 1,300 17,300 5,875 17,650 11,675 7,400 12,100 0 doses doses doses doses doses doses doses doses doses doses doses 13 77 30 74 70 0 sites 20 FQHCs 5 FQHCs 56 FQHCs 27 FQHCs 56 FQHCs FQHCs FQHCs FQHCs FQHCs FQHCs TACHC has developed a summary table with updated information regarding COVID Vaccines available with a section to preview those that are currently under evaluation for possible approval‐ Please share with your staff to provide the overview for questions they or patients may have regarding differences between -

Interfaith Annual Report 2021

ON THE COVER Michael Frishkopf, Professor of Music and Director, Canadian ANNUAL Centre for Ethnomusicology at the U of A, entertaining us at city hall with members of the Middle Eastern and North REPORT African Music Ensemble bit.ly/mename EDMONTON INTERFAITH CENTRE FOR EDUCATION & ACTION OUR VISION The Edmonton Interfaith Centre for Education and Action is recognized as a vital organization that addresses faith issues locally, nationally, and globally. We model a solidarity that embraces both diversity and commonality of faith groups. OUR MISSION The Edmonton Interfaith Centre for Education and Action promotes peace and facilitates interfaith solidarity among our members, and our local, national, and global communities, through educational programs, social action, and modelling respectful pluralism. EDMONTON INTERFAITH CENTRE FOR EDUCATION & ACTION Annual Report - 2020/21 EDMONTON INTERFAITH CENTRE FOR EDUCATION & ACTION The Edmonton Interfaith Centre for Education about local and global discrimination and to & Action was founded in December 1995 to model a non-discriminatory lifestyle. promote respect, friendship, harmony and understanding between people of various On an ongoing basis we provide speakers faiths. Our actual incorporation became to schools across Edmonton, addressing the offi cial on March 19, 1996 so we have just diversity of religious expressions found in celebrated our 25th anniversary, a major the community. The Centre facilitates visits accomplishment for a small not-for-profi t to houses of worship both for children and society! We grew out of a few local initiatives adults and coordinates interfaith prayer such as the “Edmonton Inter-Faith Group” services throughout the year. We have hosted (1987). -

Commencement Friday, May 31, 2019

THE CITY COLLEGE OF NEW YORK COMMENCEMENT FRIDAY, MAY 31, 2019 THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK Commencement Friday, May 31, 2019, 9:30 a.m. South Campus Great Lawn Presiding Vince Boudreau President, The City College of New York Academic Procession Interim Provost Tony Liss Gustavo Cepeda President, Undergraduate Student Government Emmanuel Adu Poku Executive Chair, Graduate Student Council Associate Dean Ardie Walser The Grove School of Engineering PhD Graduates Dean Mary Erina Driscoll The School of Education Elsie Nicole Figueroa and Erin N. White Dean Gilda Barabino The Grove School of Engineering Ahalya Sanjiv and Yashoma Boodhan Dean Juan Carlos Mercado The Division of Interdisciplinary Studies at the Center for Worker Education Denise Carter-Mataboge and Julie Orelien Interim Dean Gordon A. Gebert The Bernard and Anne Spitzer School of Architecture Diaa Hassan and Maria Katrina Duran Director Hillary Brown Sustainability in the Urban Environment Nicolas Maxfield and Jose Firpo Interim Dean V. Parameswaran Nair The Division of Science Valeria Grajales and John Supino Interim Dean Erica Friedman The Sophie Davis Program in Biomedical Education in the CUNY School of Medicine We are grateful for the Yardelis Maria Diaz and Charlene Kotei Dean Erec Koch generous support of Sy The Division of Humanities and the Arts and Laurie Sternberg Rafael A. Samanez and Aurora Soriano Dean Andrew Rich for their sponsorship of Colin Powell School for Civic and Global Leadership this year’s Commencement. Oneika N. Pryce, David Dam and Bryan Guichardo Academic Procession Faculty Presentation of Candidates Division of Interdisciplinary Studies at the Center for Worker Education .......Juan Carlos Mercado (continued) Reunion Classes 1949, 1959, 1968, 1969 and 1979.