Alternative Pathways to Complexity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New Perspectives on Prehispanic Highland Mesoamerica: a Macroregional Approach

Comparative Civilizations Review Volume 24 Number 24 Spring 1991 Article 4 4-1-1991 New Perspectives on Prehispanic Highland Mesoamerica: A Macroregional Approach Gary M. Feinman University of Wisconsin-Madison Linda M. Nicholas Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr Recommended Citation Feinman, Gary M. and Nicholas, Linda M. (1991) "New Perspectives on Prehispanic Highland Mesoamerica: A Macroregional Approach," Comparative Civilizations Review: Vol. 24 : No. 24 , Article 4. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/ccr/vol24/iss24/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Comparative Civilizations Review by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Feinman and Nicholas: New Perspectives on Prehispanic Highland Mesoamerica: A Macroregi NEW PERSPECTIVES ON PREHISPANIC HIGHLAND MESOAMERICA: A MACROREGIONAL APPROACH1 GARY M. FEINMAN LINDA M. NICHOLAS Many social scientists might question the potential role for ar- chaeology in the study of world systems and macroregional politi- cal economies. After all, the principal contributions to this con- temporary research domain have come from history and other social sciences (e.g., Braudel 1972; Wallerstein 1974; Wolf 1982). In addition, most of the world systems literature to date has fo- cused on Europe and other regions of the Old World. This paper takes a somewhat novel tack, one that integrates contemporary findings in archaeology and history to expand and contribute to current debates concerning the nature of ancient world systems and interregional relations. Yet, the geographic focus is not Rome or Greece or even the area between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, but rather prehispanic Mesoamerica, an area that encom- passes the southern two-thirds of what is now Mexico, as well as Guatemala, Belize, and parts of Honduras, Costa Rica, and El Salvador. -

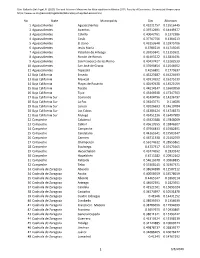

No. State Municipality Gini Atkinson 1 Aguascalientes Aguascalientes

Cite: Gallardo Del Angel, R. (2020) Gini and Atkinson Measures for Municipalities in Mexico 2015. Faculty of Economics. Universidad Veracruzana. https://www.uv.mx/personal/rogallardo/laboratory-of-applied-economics/ No. State Municipality Gini Atkinson 1Aguascalientes Aguascalientes 0.43221757 0.15516445 2Aguascalientes Asientos 0.39712691 0.14449377 3Aguascalientes Calvillo 0.40042761 0.1372586 4Aguascalientes Cosío 0.37767756 0.1304213 5Aguascalientes El Llano 0.43253648 0.15975706 6Aguascalientes Jesús María 0.3780219 0.11715045 7Aguascalientes Pabellón de Arteaga 0.39355841 0.13155921 8Aguascalientes Rincón de Romos 0.41403222 0.15831631 9Aguascalientes San Francisco de los Romo 0.40437427 0.15282539 10Aguascalientes San José de Gracia 0.37699854 0.12548952 11Aguascalientes Tepezalá 0.4256891 0.1779637 12Baja California Enseda 0.43223187 0.16224693 13Baja California Mexicali 0.43914592 0.16275139 14Baja California Playas de Rosarito 0.42097628 0.14521059 15Baja California Tecate 0.44214147 0.16600958 16Baja California Tijua 0.45446938 0.17347503 17Baja California Sur Comondú 0.41404796 0.14236797 18Baja California Sur La Paz 0.36343771 0.114026 19Baja California Sur Loreto 0.42026693 0.14610784 20Baja California Sur Los Cabos 0.41386124 0.14718573 21Baja California Sur Mulegé 0.42451236 0.16497989 22Campeche Calakmul 0.45923388 0.17848009 23Campeche Calkiní 0.43610555 0.15846507 24Campeche Campeche 0.47966433 0.19382891 25Campeche Candelaria 0.44265541 0.17503347 26Campeche Carmen 0.46711338 0.21462959 27Campeche Champotón 0.56174612 -

Gifts and Commodities (Second Edition)

GIFTS AND COMMODITIES Hau BOOKS Executive Editor Giovanni da Col Managing Editor Sean M. Dowdy Editorial Board Anne-Christine Taylor Carlos Fausto Danilyn Rutherford Ilana Gershon Jason Throop Joel Robbins Jonathan Parry Michael Lempert Stephan Palmié www.haubooks.com GIFTS AND COMMODITIES (SECOND EditIon) C. A. Gregory Foreword by Marilyn Strathern New Preface by the Author Hau Books Chicago © 2015 by C. A. Gregory and Hau Books. First Edition © 1982 Academic Press, London. All rights reserved. Cover and layout design: Sheehan Moore Typesetting: Prepress Plus (www.prepressplus.in) ISBN: 978-0-9905050-1-3 LCCN: 2014953483 Hau Books Chicago Distribution Center 11030 S. Langley Chicago, IL 60628 www.haubooks.com Hau Books is marketed and distributed by The University of Chicago Press. www.press.uchicago.edu Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. For Judy, Polly, and Melanie. Contents Foreword by Marilyn Strathern xi Preface to the first edition xv Preface to the second edition xix Acknowledgments liii Introduction lv PART ONE: CONCEPTS I. THE COmpETING THEOriES 3 Political economy 3 The theory of commodities 3 The theory of gifts 9 Economics 19 The theory of modern goods 19 The theory of traditional goods 22 II. A framEWORK OF ANALYSIS 25 The general relation of production to consumption, distribution, and exchange 26 Marx and Lévi-Strauss on reproduction 26 A simple illustrative example 30 The definition of particular economies 32 viii GIFTS AND COMMODITIES III.FTS GI AND COMMODITIES: CIRCULATION 39 The direct exchange of things 40 The social status of transactors 40 The social status of objects 41 The spatial aspect of exchange 44 The temporal dimension of exchange 46 Value and rank 46 The motivation of transactors 50 The circulation of things 55 Velocity of circulation 55 Roads of gift-debt 57 Production and destruction 59 The circulation of people 62 Work-commodities 62 Work-gifts 62 Women-gifts 63 Classificatory kinship terms and prices 68 Circulation and distribution 69 IV. -

A Re-Assessment of Government and Political Institutions of Old Oyo Empire

QUAESTUS MULTIDISCIPLINARY RESEARCH JOURNAL A RE-ASSESSMENT OF GOVERNMENT AND POLITICAL INSTITUTIONS OF OLD OYO EMPIRE Oluwaseun Samuel OSADOLA, Oluwafunke Adeola ADELEYE Abstract: Oyo Empire was the most politically organized entity founded by the Yoruba speaking people in present-day Nigeria. The empire was well organized, influential and powerful. At a time it controlled the politics and commerce of the area known today as Southwestern Nigeria. It, however, serves as a paradigm for other sub-ethnic groups of Yoruba derivation which were directly or indirectly influenced by the Empire before the coming of the white man. To however understand the basis for the political structure of the current Yorubaland, there is the need to examine the foundational structure from which they all took after the old Oyo Empire. This paper examines the various political structures that made up government and governance in the Yoruba nation under the political control of the old Oyo Empire before the coming of the Europeans and the establishment of colonial administration in the 1900s. It derives its data from both primary and secondary sources with a detailed contextual analysis. Keywords: Old Oyo Empire INTRODUCTION Pre-colonial systems in Nigeria witnessed a lot of alterations at the advent of the British colonial masters. Several traditional rulers tried to protect and preserve the political organisation of their kingdoms or empires but later gave up after much pressure and the threat from the colonial masters. Colonialism had a significant impact on every pre- colonial system in Nigeria, even until today.1 The entire Yoruba country has never been thoroughly organized into one complete government in a modern sense. -

Cash on the Table 1

Cash on the Table 1 Introduction Markets and Moralities Edward F. Fischer Moral values inform economic behavior.1 On its face, this is an unas- sailable proposition. Think of the often spiritual appeal of consumer goods or the value-laden stakes of upward or downward mobility. Think about the central role that moral questions regarding poverty, access to health care, the tax code, property and land rights, and corruption play in the shap- ing of modern governments, societies, and social movements. Think of fair trade coffee and organic produce and the thrift expressed in Walmart’s everyday low prices. The moral aspects of the marketplace have never been so contentious or consequential. Despite this relationship, the realm of economics is often treated as a world unto itself, a domain where human behavior is guided not by emo- tions, beliefs, moralities, or the passions that fascinate anthropologists but by the hard calculus of rational choices. The attraction of this Homo eco- nomicus paradigm rests in its parsimony, in the way it translates the chaos of everyday life and human behavior into a metric system complete with mathematical models based on assumptions about self-interest and maxi- mization (see Beckert 2002; Carrier 1997; Fullbrook 2004; Stiglitz 1993). Authors of economics textbooks often liken the workings of markets to nat- ural forces, distancing themselves from the field’s historical roots in phi- losophy and ethics. On issues of value and morality, many economists plead COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL www.sarpress.org 3 Edward F. Fischer agnosticism—it is not a question of good or bad, they say, but rather of effi- cient or inefficient (see Becker 1996; Becker and Becker 1996; Samuelson 1976). -

Multi-National Conservation of Alligator Lizards

MULTI-NATIONAL CONSERVATION OF ALLIGATOR LIZARDS: APPLIED SOCIOECOLOGICAL LESSONS FROM A FLAGSHIP GROUP by ADAM G. CLAUSE (Under the Direction of John Maerz) ABSTRACT The Anthropocene is defined by unprecedented human influence on the biosphere. Integrative conservation recognizes this inextricable coupling of human and natural systems, and mobilizes multiple epistemologies to seek equitable, enduring solutions to complex socioecological issues. Although a central motivation of global conservation practice is to protect at-risk species, such organisms may be the subject of competing social perspectives that can impede robust interventions. Furthermore, imperiled species are often chronically understudied, which prevents the immediate application of data-driven quantitative modeling approaches in conservation decision making. Instead, real-world management goals are regularly prioritized on the basis of expert opinion. Here, I explore how an organismal natural history perspective, when grounded in a critique of established human judgements, can help resolve socioecological conflicts and contextualize perceived threats related to threatened species conservation and policy development. To achieve this, I leverage a multi-national system anchored by a diverse, enigmatic, and often endangered New World clade: alligator lizards. Using a threat analysis and status assessment, I show that one recent petition to list a California alligator lizard, Elgaria panamintina, under the US Endangered Species Act often contradicts the best available science. -

The Emergence of Pristine States

The Emergence of Pristine States Henri J. M. Claessen Leiden University ABSTRACT In this article the emergence of the Pristine State will be considered. First, I will present an overview of the applied method. Then seven cases of – probable – Pristine States are described. This makes a comparative research possible. As the case studies have been de- scribed with the help of the Complex Interaction Model, the com- parative part is also based upon this approach. From the compari- sons it appeared that all cases developed in a situation of relative wealth. They were not a consequence of hunger or population pres- sure. Nor could the often mentioned role of war be established as crucial in the formation of these states. War, as far as it occurred, was rather a consequence than a condition of state formation. 1. PRELIMINARY REMARKS In 1967, Morton H. Fried introduced the concept of the pristine state in The Evolution of Political Society, stating that ‘all contemporary states, even those that seem to be lineally descended from the states of high antiquity, like China, are really secondary states; the pristine states perished long ago’ (Fried 1967: 231). The pristine states were those that ‘emerged from stratified societies and experienced the slow, autochthonous growth of specialized formal instruments of social control out of their own needs for these institutions’ (Ibid.). The institutions grew and a leader – a priest, a warrior, a man- ager, or a charismatic person – came to the fore, and started to use his power. Gradually the organization of such a polity developed into an incipient early state (term in Claessen 1978, 2014). -

Play As a Foundation for Hunter-Gatherer Social Existence

Play as a Foundation for Hunter- Gatherer Social Existence • Peter Gray The author offers the thesis that hunter-gatherers promoted, through cultural means, the playful side of their human nature and this made possible their egalitar- ian, nonautocratic, intensely cooperative ways of living. Hunter-gatherer bands, with their fluid membership, are likened to social-play groups, which people could freely join or leave. Freedom to leave the band sets the stage for the individual autonomy, sharing, and consensual decision making within the band. Hunter- gatherers used humor, deliberately, to maintain equality and stop quarrels. Their means of sharing had gamelike qualities. Their religious beliefs and ceremonies were playful, founded on assumptions of equality, humor, and capriciousness among the deities. They maintained playful attitudes in their hunting, gathering, and other sustenance activities, partly by allowing each person to choose when, how, and how much they would engage in such activities. Children were free to play and explore, and through these activities, they acquired the skills, knowl- edge, and values of their culture. Play, in other mammals as well as in humans, counteracts tendencies toward dominance, and hunter-gatherers appear to have promoted play quite deliberately for that purpose. I am a developmental/evolutionary psychologist with a special inter- est in play. Some time ago, I began reading the anthropological literature on hunter-gatherer societies in order to understand how children’s play might contribute to children’s education in those societies. As I read, I became in- creasingly fascinated with hunter-gatherer social life per se. The descriptions I read, by many different researchers who had observed many different hunter- gatherer groups, seemed to be replete with examples of humor and playfulness in adults, not just in children, in all realms of hunter-gatherers’ social existence. -

Theocracy Metin M. Coşgel Thomas J. Miceli

Theocracy Metin M. Coşgel University of Connecticut Thomas J. Miceli University of Connecticut Working Paper 2013-29 November 2013 365 Fairfield Way, Unit 1063 Storrs, CT 06269-1063 Phone: (860) 486-3022 Fax: (860) 486-4463 http://www.econ.uconn.edu/ This working paper is indexed on RePEc, http://repec.org THEOCRACY by Metin Coşgel* and Thomas J. Miceli** Abstract: Throughout history, religious and political authorities have had a mysterious attraction to each other. Rulers have established state religions and adopted laws with religious origins, sometimes even claiming to have divine powers. We propose a political economy approach to theocracy, centered on the legitimizing relationship between religious and political authorities. Making standard assumptions about the motivations of these authorities, we identify the factors favoring the emergence of theocracy, such as the organization of the religion market, monotheism vs. polytheism, and strength of the ruler. We use two sets of data to test the implications of the model. We first use a unique data set that includes information on over three hundred polities that have been observed throughout history. We also use recently available cross-country data on the relationship between religious and political authorities to examine these issues in current societies. The results provide strong empirical support for our arguments about why in some states religious and political authorities have maintained independence, while in others they have integrated into a single entity. JEL codes: H10, -

Why Do the Indians Wear Adidas? Or, Culture Contact and the Relations of Consumption Richard R

1984 Unpublished Article Why do the Indians Wear Adidas? Or, Culture Contact and the Relations of Consumption Richard R. Wilk and Eric J. Arnould Abstract Page 1 of 31 The study of the consumption of goods has never achieved the JBA 5(1): 6-36 prominence in anthropology of either production or exchange. Yet the Autumn 2016 accelerating consumption of western goods in non-western societies is © The Author(s) 2016 one of the most obtrusive cultural and economic trends of the last three ISSN 2245-4217 centuries. This article addresses the general issue of why goods flow www.cbs.dk/jba between cultural groups by re-examining the concept of consumption. It raises questions of importance to studies of development, material culture, ethnohistory, and symbolic anthropology. Keywords Economic anthropology, consumption, acculturation, symbolic anthropology, material culture Wilk and Arnould / Why do the Indians Wear Adidas? Introduction Peruvian Indians carry around small rectangular rocks painted to look like transistor radios.1 San Blas Cuna households hoard boxes of dolls, safety pins, children's hats and shoes, marbles, enamelware kettles, and bedsheets with pillowcases in their original cellophane wrappings. Japanese newlyweds cut three-tiered white frosted inedible cakes topped with plastic figures in western dress. Q’eqchi’ Maya swidden farmers relax at night listening to Freddie Fender on a portable cassette player while Bana tribesmen in Kako, Ethiopia, pay a hefty price to look through a Viewmaster at “Pluto Tries to Become a Circus Dog.” Tibetans, bitterly opposed to Chinese rule, sport Mao caps. Young Wayana Indians in Surinam spend hours manipulating a Rubik's cube. -

Movilidad Y Desarrollo Regional En Oaxaca

ISSN 0188-7297 Certificado en ISO 9001:2000‡ “IMT, 20 años generando conocimientos y tecnologías para el desarrollo del transporte en México” MOVILIDAD Y DESARROLLO REGIONAL EN OAXACA VOL1: REGIONALIZACIÓN Y ENCUESTA DE ORIGÉN Y DESTINO Salvador Hernández García Martha Lelis Zaragoza Manuel Alonso Gutiérrez Víctor Manuel Islas Rivera Guillermo Torres Vargas Publicación Técnica No 305 Sanfandila, Qro 2006 SECRETARIA DE COMUNICACIONES Y TRANSPORTES INSTITUTO MEXICANO DEL TRANSPORTE Movilidad y desarrollo regional en oaxaca. Vol 1: Regionalización y encuesta de origén y destino Publicación Técnica No 305 Sanfandila, Qro 2006 Esta investigación fue realizada en el Instituto Mexicano del Transporte por Salvador Hernández García, Víctor M. Islas Rivera y Guillermo Torres Vargas de la Coordinación de Economía de los Transportes y Desarrollo Regional, así como por Martha Lelis Zaragoza de la Coordinación de Ingeniería Estructural, Formación Posprofesional y Telemática. El trabajo de campo y su correspondiente informe fue conducido por el Ing. Manuel Alonso Gutiérrez del CIIDIR-IPN de Oaxaca. Índice Resumen III Abstract V Resumen ejecutivo VII 1 Introducción 1 2 Situación actual de Oaxaca 5 2.1 Situación socioeconómica 5 2.1.1 Localización geográfica 5 2.1.2 Organización política 6 2.1.3 Evolución económica y nivel de desarrollo 7 2.1.4 Distribución demográfica y pobreza en Oaxaca 15 2.2 Situación del transporte en Oaxaca 17 2.2.1 Infraestructura carretera 17 2.2.2 Ferrocarriles 21 2.2.3 Puertos 22 2.2.4 Aeropuertos 22 3 Regionalización del estado -

Carneiro's Social Circumscription Theory: Necessary but Not Sufficient

Carneiro's Social Circumscription Theory: Necessary but not Sufficient D. Blair Gibson El Camino College Firstly, let me state what an honor and delight it is to be asked to revisit one of the seminal contributions by a towering thinker of modern anthropology. Robert Carneiro's 1970 paper succeeded in weaving many of the strands of the cultural ecology and neo- evolutionism of the 1950s and 60s into a succinct theory of state origins. This theory in turn influenced and inspired many treat- ments having to do with the growth of complex societies, espe- cially those of the New World. His ‘reformulation’ represents the author's effort to reaffirm the basic tenets of the theory and estab- lish its applicability on a global scale. Carneiro starts his treatment with a summary of the past and present thinking on the origins of the state whereby he categorizes theories of state origins as either voluntaristic or coercive. By dint of these categories it has proven possible to discern a dichotomy in the underlying attitudes of those who have developed theories of social complexity, but these categories are not comprehensive and the examples that he provides are not all apt. The voluntaristic theories of yore presented chiefdoms and states as emerging to re- solve some structural problem such as the prevention of food scar- city or the provision of access to unequally distributed resources. To characterize Wittfogel's hydraulic hypothesis as a voluntaristic theory of state evolution is certainly problematic on two counts: Wittfogel was not so much concerned with explaining state origins as he was with detailing the character of the ‘hydraulic/apparatus’ state, and secondly, Wittfogel states that his theory includes ele- ments of coercion (Wittfogel 1957: 26).