Guidelines Approximation with Eu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Points of View of Monetary Integration Maturity) 1

THE EURO AND CENTRAL EUROPE (FROM POINTS OF VIEW OF MONETARY INTEGRATION MATURITY) 1 TIBOR PALANKAI1 1Emeritus Professor of Corvinus University of Budapest E-mail:[email protected] The paper discusses the frameworks and development of the introduction of the Euro in Central Europe, with a focus on pre-entry countries (Czechia, Hungary, Poland, Romania and Croatia). The main elements of monetary integration maturity are the state of real-integration (possibilities of large saving in transaction costs), meeting the criteria of functioning market economy and the single market; macro-economic stability and meeting the Maastricht criteria; and shortcomings of absorption (integration) capacities of the EU. Controversial questions are also discussed, such as requirements concerning inflation, the budget deficit or exchange rate stability. The paper argues that the countries under scrutiny show diverging courses of action and policies, public support is also unclear, and the interests of TNCs and political elites contradict each other. Cultural, legal, security or emotional factors will pay a key role in eventual adoption, and prospects also depend on the solution of the current debt and migration crises. Keywords: Euro and Central Europe, monetary maturity, diverging interests, attitudes, policies, and prospects. JEL-codes: F2, F3 1. FRAMEWORK OF MONETARY INTEGRATION FOR THE CENTRAL AND EASTERN EUROPEAN NEW MEMBERS The full EU membership of CEE countries assumes their full EMU participation. This corresponds to the Copenhagen accession criteria, namely they should have the “ability to take on the obligations of membership, including adherence to the aims of political, economic and monetary union”. They have no possibility of opting out, like the United Kingdom and Denmark. -

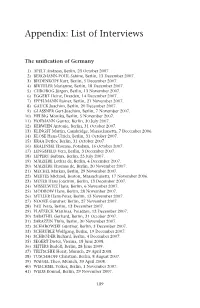

Appendix: List of Interviews

Appendix: List of Interviews The unification of Germany 1) APELT Andreas, Berlin, 23 October 2007. 2) BERGMANN-POHL Sabine, Berlin, 13 December 2007. 3) BIEDENKOPF Kurt, Berlin, 5 December 2007. 4) BIRTHLER Marianne, Berlin, 18 December 2007. 5) CHROBOG Jürgen, Berlin, 13 November 2007. 6) EGGERT Heinz, Dresden, 14 December 2007. 7) EPPELMANN Rainer, Berlin, 21 November 2007. 8) GAUCK Joachim, Berlin, 20 December 2007. 9) GLÄSSNER Gert-Joachim, Berlin, 7 November 2007. 10) HELBIG Monika, Berlin, 5 November 2007. 11) HOFMANN Gunter, Berlin, 30 July 2007. 12) KERWIEN Antonie, Berlin, 31 October 2007. 13) KLINGST Martin, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 7 December 2006. 14) KLOSE Hans-Ulrich, Berlin, 31 October 2007. 15) KRAA Detlev, Berlin, 31 October 2007. 16) KRALINSKI Thomas, Potsdam, 16 October 2007. 17) LENGSFELD Vera, Berlin, 3 December 2007. 18) LIPPERT Barbara, Berlin, 25 July 2007. 19) MAIZIÈRE Lothar de, Berlin, 4 December 2007. 20) MAIZIÈRE Thomas de, Berlin, 20 November 2007. 21) MECKEL Markus, Berlin, 29 November 2007. 22) MERTES Michael, Boston, Massachusetts, 17 November 2006. 23) MEYER Hans Joachim, Berlin, 13 December 2007. 24) MISSELWITZ Hans, Berlin, 6 November 2007. 25) MODROW Hans, Berlin, 28 November 2007. 26) MÜLLER Hans-Peter, Berlin, 13 November 2007. 27) NOOKE Günther, Berlin, 27 November 2007. 28) PAU Petra, Berlin, 13 December 2007. 29) PLATZECK Matthias, Potsdam, 12 December 2007. 30) SABATHIL Gerhard, Berlin, 31 October 2007. 31) SARAZZIN Thilo, Berlin, 30 November 2007. 32) SCHABOWSKI Günther, Berlin, 3 December 2007. 33) SCHÄUBLE Wolfgang, Berlin, 19 December 2007. 34) SCHRÖDER Richard, Berlin, 4 December 2007. 35) SEGERT Dieter, Vienna, 18 June 2008. -

The EU's Normative Power

The EU’s Normative Power – Its Greatest Strength or its Greatest Weakness? By Tornike Metreveli The Starting Point The growing influence of the European Union (EU) on the international political arena and at the same time its “particular kind” of characteristics as an international player appears to be a widely debated issue among various scholars of social sciences over the last decades. During this period a wide range of theories and concepts have attributed various epithets to the EU and tried to explain its power in different, sometimes controversial ways. Consequently the descriptions of the EU in international relations vary from it being a “Kantian paradise” (Kagan, 2004), a “vanishing mediator” (Manners, 2006:.174) to “an economic giant, a political dwarf, and a military worm” (Eyskens, 1991). For some scholars the concept of the EU goes beyond the bold epithets and is analyzed from the critical-social theoretical perspective, where the latter was hypothesized as an actor that spread its own norms beyond its borders and whose power lies in its system of values and forms of relations with the outer world (Manners, 2002). Having said this, the article tries to focus on this theoretical approach while addressing this “unique political animal” (Piris, 2010: 337). Thus, the concept pioneered by Ian Manners, particularly the idea of Europe’s “normative power” (NPE hereafter), is the central point of departure of this paper; and the critical analysis of its greatest strengths and weaknesses is the article’s main objective. Divided in three parts, the paper firstly focuses on the conceptual analysis of the NPE, and its definitions. -

The Recognition of Diplomas and the Free Movement of Professionals in the European Union: Fifty Years of Experiences

The Recognition of Diplomas and the Free Movement of Professionals in the European Union: Fifty Years of Experiences HILDEGARD SCHNEIDER SJOERD CLAESSENS MAASTRICHT UNIVERSITY 1. INTRODUCTION This year we celebrate in Europe the 50th anniversary of the entering into force of the Treaty of Rome establishing the European Economic Community. After half a century of European integration it is an appropriate moment to look back on the achievements realized in this period. This paper wants to address specifically the issues of professional mobility, qualification recognition and the developments towards a European Space of Education. Special attention will be given to the increasing international mobility of the legal profession and the consequences of this development for the legal education on academic as well as professional level in the Member States of the European Union. One of the main goals of the E(E)C Treaty from its very beginning has been the creation a common market for all economic activities. This includes the free movement of professionals. National rules which had the effect of preventing persons from providing cross border professional services or establishing themselves in another Member State had to be progressively abolished. Barriers to mobility, such as the requirement of a national diploma or language requirements, can as much constitute obstacles to the completion of the internal market as e.g. the use of different safety standards for technical goods. As there is no common educational system in Europe and the routes to professional and trade activities vary significantly between the Member States these differences can cause serious barriers to the free movement of persons. -

Policies and Politics of the European Union

Policies and Politics of the European Union Edited by Jaros³aw Jañczak Faculty of Political Science and Journalism Adam Mickiewicz University Poznañ 2010 Review: Jerzy Babiak, Ph.D., AMU Professor Cover designed by: Adam Czerneñko Front page photo by: Przemys³aw Osiewicz © Copyright by Faculty of Political Science and Journalism Press, Adam Mickiewicz University, 89 Umultowska Street, 61-614 Poznañ, Poland, Tel.: 61 829 65 08 ISBN 978-83-60677-99-5 Sk³ad komputerowy – „MRS” 60-408 Poznañ, ul. P. Zo³otowa 23, tel. 61 843 09 39 Druk i oprawa – Zak³ad Graficzny UAM – 61-712 Poznañ, ul. H. Wieniawskiego 1 Table of Contents Introduction ..................... 5 Maciej Walkowski: The Monetary Integration Process in Europe. An Analysis of Potential Threats and Opportunities Connected with the Introduction of the Euro in Poland ........ 7 Ekaterina Islentyeva: EU Commission’s Cooperation with the non-EU Countries in the Field of the Competition Policy ...... 21 Robert Kmieciak: Local Government in the Process of Implementation of the European Union’s Regional Policy in Poland ..... 35 Lika Mkrtchyan: Armenia and Turkey: Historic Rivals or Modern Neighbors? Turkey’s Way to Europe (Turkey’s European Integration from Armenia’s Perspective) . 43 Przemys³aw Osiewicz: The European Union and its Attitude Towards Turkey’s EU Membership Bid After 2005: Between Policy and Politics .............. 53 Agnieszka Wójcicka: Sweden and Poland. Nordicization versus Europeanization Processes ............... 63 Knut Erik Solem: Democracy, Integration Theory and Community-building in Small States: The Case of Norway . 85 Jaros³aw Jañczak: De-Europeanization and Counter-Europeanization as Reversed Europeanization. In Search of Categorization . 99 Piotr Tosiek: Comitology Implementation of EU Policies – Democratic Intergovernmentalism? .......... -

SLOVAKIA and the EURO: HOW SLOVAKIA HAS OUT- PACED ITS VISEGRÁD NEIGHBORS on the PATH to ECONOMIC and MONETARY UNION Jill Carroll

FIVE SLOVAKIA AND THE EURO: HOW SLOVAKIA HAS OUT- PACED ITS VISEGRÁD NEIGHBORS ON THE PATH TO ECONOMIC AND MONETARY UNION Jill Carroll Adoption of the European common currency, the euro, is a requirement for the twelve New Member States which joined the European Union in 2004 and 2007. The Maastricht Treaty imposes macroeconomic requirements on New Member States before they can replace their national currencies with the euro. The aim of this paper is to examine the political environment of the Visegrád states and to explain why Slovakia is the only country among the four Central European states to have adopted the euro. This paper argues that the political will to cut welfare spending and a country’s economic size have been the most important factors in determining when a Central European state will adopt the euro. Jill Carroll will receive her Masters in Political Science-Transatlantic Relations from the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill in May 2011. She received a Bachelor’s in Business Administration in 2003 and plans to pursue a career in which she can impact social policies through research and advocacy. Slovakia and the Euro 66 INTRODUCTION The Maastricht Treaty, adopted in 1993, officially established the European Union (EU) and laid the foundations for the creation of the euro as the common currency among its member states. Adoption of the euro is a requirement of EU accession for the twelve countries that joined the union in May 2004 and January 2007. There are no special opt-outs as there were for the UK and Denmark, although as Sweden has demonstrated, there is also no effective deadline to join the eurozone, the region comprised of EU members that use the euro as their national currency. -

Slovak Republic's Accession to the European Union

Nr 12 ROCZNIK INTEGRACJI EUROPEJSKIEJ 2018 Krzysztof Żarna DOI : 10.14746/rie.2018.12.22 Uniwersytet Rzeszowski ORCID: 0000-0002-6965-8682 Slovak Republic’s accession to the European Union Introductory remarks the aim of this article is to present the specificity of the accession process of the Slovak Republic to the European Union in comparison to other countries of Central Europe. the author attempted to find answers to the following three questions: What were the successive stages of slovakian accession to EU; what were the reasons for negotiating with slovakia later than with the other countiries of the same region; what issues were the most difficult during the course of the negotiation proces? the article is based on the assumption that the politics of Vladimir Mečiar, in par- ticular human rights breaches, negatively inluenced the process of slovakia’s accession to the European Union. Another hypothesis is that in comparison to other countries of Central Europe, slovak political parties reached a national consensus concerning ac- cession to the European Union. In order to provide answers to the research questions and verify the hypothesis, the au- thor used a numer of different research methods specific to the political sciences: historical analysis, decision – making analysis, institutional and legal analysis and system analysis. Establishing cooperation the slovak republic is a political descentant of Czehoslovakia, which established diplomatic ties with the European Community (EC) in the late 1980s. This was made possible by signing a common declaration between the European Economic Com- munity (EEC) and the Council for Mutual Economic Assistance (CMEA) in Luxem- burg on the 25th of June 1988. -

Accession of Third Countries to the European Union Vs

Faculty of Law and Criminology Academic Year 2018-2019 Exam Session [1] Accession of Third Countries to the European Union vs. Brexit: A Comparison of the Transitional Agreements and Their Implication for the EU Internal Market LLM Paper by FAUVE BEX Student number: 01810919 Promotor: Prof. Dr. Inge GOVAERE Supervisor: Ms. Joyce DE CONINCK ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to express my sincere gratitude to Professor Doctor Inge Govaere who accepted to mentor me in the redaction of this study and, more specifically, accepted that I would partly work on Brexit, a subject which I have aspired to delve into since quite some time. I am further grateful to Professor Doctor Ellen Desmet, Ms. Joyce De Coninck, Ms. Laurence Lambert and Ms. Birte Scorpion who made me grow intellectually and taught me to be as critical as possible in the analysis of subjects, efficient, have self-confidence and persevere and this, through their moot court coaching. Lastly, I would like to thank my dad, Elyse and Matthias for their thorough proofreading, my moot court team mates, without whom courage would have failed to stay with me until the submission, and my family and friends to always support my endeavours. TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .............................................................................................................................. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER 1. ACCESSION VS. WITHDRAWAL: -

Domestic Politics Comes First—Euro Adoption Stretegies in Central Europe

Domestic Politics Comes First—Euro Adoption Stretegies in Central Europe: The Cases of the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland By Assem Dandashly License, Lebanese University, 2000 M.A., Lebanese American University, 2004 A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department of Political Science © Assem Dandashly, 2012 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This dissertation may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopying or other means, without the permission of the author. Domestic Politics Comes First—Euro Adoption Stretegies in Central Europe: The Cases of the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland By Assem Dandashly License, Lebanese University, 2000 M.A., Lebanese American University, 2004 Supervisory Committee Professor Amy C. Verdun, Supervisor (Department of Political Science) Professor Colin J. Bennett, Departmental Member (Department of Political Science) Professor Oliver Schmidtke, Departmental Member (Department of Political Science) Professor Emmanuel Brunet-Jailly, Outside Member (School of Public Administration) Professor Mitchell P. Smith, Additional Member (University of Oklahoma, Department of Political Science) ii Supervisory Committee Professor Amy C. Verdun, Supervisor (Department of Political Science) Professor Colin J. Bennett, Departmental Member (Department of Political Science) Professor Oliver Schmidtke, Departmental Member (Department of Political Science) Professor Emmanuel Brunet-Jailly, Outside Member (School of Public Administration) -

Consolidated.Treaties.Draft.Pdf

Consolidated version of the Treaties amended by the Treaty of Lisbon Draft version COMPILED BY PEADAR Ó BROIN INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AND EUROPEAN AFFAIRS / INSTITIÚID GNÓTHAÍ IDIRNÁISIÚNTA AGUS EORPACHA (www.iiea.com) CONSOLIDATED VERSION OF THE TREATIES compiled by Peadar ó Broin [email protected] ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ 1 INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AND EUROPEAN AFFAIRS / INSTITIÚID GNÓTHAÍ IDIRNÁISIÚNTA AGUS EORPACHA (www.iiea.com) ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ ȱ © 2007 Institute of International and European Affairs. All rights reserved. This publication may be reproduced in full or in part if accompanied with the following citation: Peadar ó Broin, Consolidated version of the Treaties amended by the Treaty of Lisbon, Institute of International and European Affairs, Dublin, Ireland, November 2007. As an independent forum, the Institute does not express opinions of its own. The Treaty annotations contained in this publication are solely the responsibility of the author. For electronic copies of this report, please visit www.iiea.com ISBN: x-xxx-xxx-xx-x / DRAFT 2 INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AND EUROPEAN AFFAIRS / INSTITIÚID GNÓTHAÍ IDIRNÁISIÚNTA AGUS EORPACHA (www.iiea.com) Contents Treaty on European Union ....................................................................................................4 Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union ..........................................................40 3 INSTITUTE OF INTERNATIONAL AND EUROPEAN AFFAIRS / INSTITIÚID GNÓTHAÍ IDIRNÁISIÚNTA AGUS EORPACHA (www.iiea.com) TREATY -

EUI Working Papers MWP 2007/02

EUI Working Papers MWP 2007/02 The External Dimension of the Acquis Communautaire Roman Petrov EUROPEAN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE MAX WEBER PROGRAMME The External Dimension of the Acquis Communautaire ROMAN PETROV EUI W orking Paper MWP No. 200 7/02 This text may be downloaded for personal research purposes only. Any additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copy or electronically, requires the consent of the author(s), editor(s). If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the working paper or other series, the year, and the publisher. The author(s)/editor(s) should inform the Max Weber Programme of the EUI if the paper is to be published elsewhere, and should also assume responsibility for any consequent obligation(s). ISSN 1830-7 728 © 2007 Roman Petrov Printed in Italy European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) Italy http://www.eui.eu/ http://cadmus.eui.eu/ Abstract The aim of this article is to study the concept of the acquis communautaire in the domain of EU external relations. It is argued that the acquis communautaire varies according to the specific aims of its internal and external applications. The main objective of the acquis communautaire in its internal dimension is to enable the consistent development of the EU while preserving EC/EU patrimony by Member States. The objective of the acquis communautaire application in its external dimension is to push third countries to the forefront of the acquired level of economic, political and legal cooperation achieved by the EU. -

Revisiting the Powers of the Rotating Presidency of the Council of the Eu

UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI MILANO UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI GENOVA UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI PAVIA PhD PROGRAMME POLITICAL STUDIES – 31st cohort DOCTORAL THESIS MANY POLICIES, LITTLE TIME: REVISITING THE POWERS OF THE ROTATING PRESIDENCY OF THE COUNCIL OF THE EU SPS/04, SPS/01, SPS/11 PhD CANDIDATE AUSTĖ VAZNONYTĖ SUPERVISOR PROF. FABIO FRANCHINO PhD DIRECTOR PROF. MATTEO JESSOULA ACADEMIC YEAR 2017/2018 The PhD programme Political Studies (POLS) (31st cohort) stems from the collaboration of three Universities, namely Università degli Studi di Genova, Università degli Studi di Milano, Università degli Studi di Pavia. The University of Milan serves as the administrative headquarters and provides the facilities for most teaching activities. Abstract The rotating Presidency of the Council of the European Union, once a key actor in the European decision-making process, was substantially weakened after the Treaty of Lisbon. Nonetheless, it maintains important competences, characterising the Presidency’s stance in the Council of the EU. Against this background, while focusing on one of the main responsibilities granted to the rotating chair – agenda control of the Council – this dissertation evaluates the extent to which the rotating Presidency is able to leave an imprint on the institution’s agenda, as well as the legislative outputs of the EU. In doing so, the research applies a widespread methodological approach, ranging from statistical analyses, quantitative text-analyses to qualitative comparative case studies. Throughout its four chapters, this dissertation addresses the key institutional assets possessed by the rotating Presidency: agenda-setting, agenda-structuring and agenda-exclusion powers, as presented by Tallberg (2003). Taking into consideration the lack of longitudinal analyses of rotating Presidency agendas, especially after the Treaty of Lisbon, this dissertation provides several contributions.